Canada's Ice shelves are collapsing at a shocking rate. Since the summer of 2005 half of Canada's ice shelves have shattered into icebergs and flowed into the Arctic ocean. These thick ice shelves, which built up over thousands of years at the coastal end of glacial valleys, lost half their area in just 6 years. The loss of these ice shelves may allow glaciers to flow faster into the sea, because they can act like dams at the coastal end of large glaciers.

This summer almost all of one major ice shelf broke up and Canada's largest remaining shelf split into 2 pieces.

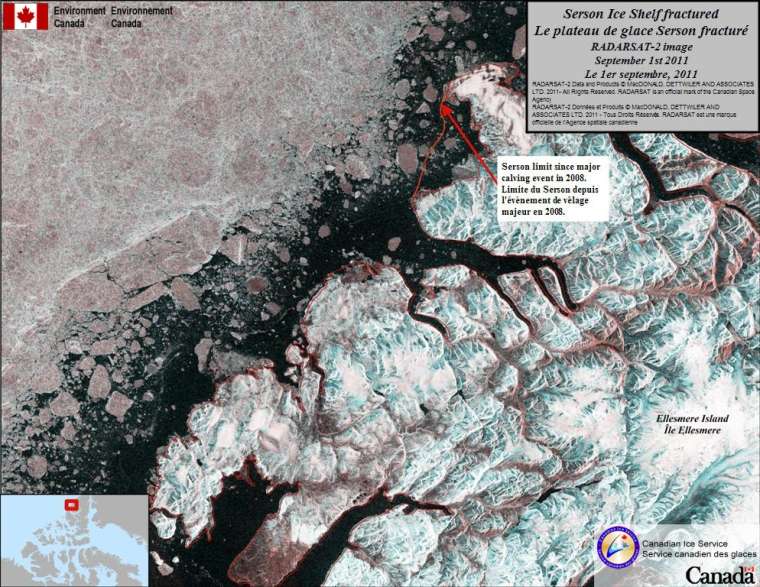

The red line shows where the Serson ice shelf used to be.

This summer alone, most of the Serson Ice Shelf broke away and the Ward Hunt Ice Shelf has now split into two separate pieces. This ice loss equals up to three billion tonnes or about 500 times the mass of the Great Pyramid of Giza.

A large area of the Ward Hunt ice shelf shattered in the summer of 2008.

“Since the end of July, pieces equaling one and a half times the size of Manhattan Island have broken off,” says Luke Copland, researcher in the Department of Geography at the University of Ottawa. He warns that oil companies need to sit up and take notice as more icebergs will be floating down from the North and may threaten rigs in locations such as the Beaufort and Chukchi seas.Mueller blames a combination of warmer temperatures and open water for recent ice shelf calving. “The ice shelves were formed and sustained in a different climate than what we have now. As they disappear, it implies we are returning to conditions unseen in the Arctic for thousands of years.”

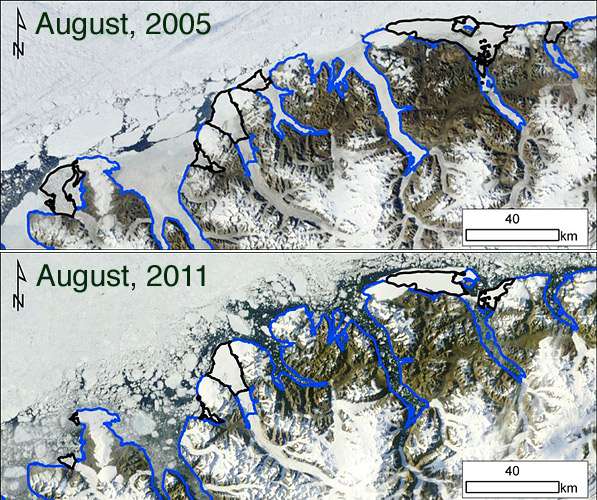

In these satellite images, taken at the end of August, 2005 and August, 2011, respectively, the Ellesmere Island ice shelves are outlined in black. In the 2011 image, the Serson shelf, located on the far left, has decreased in size significantly, while the Ward Hunt shelf, located on the far right, has split into two pieces.

The Carleton University press release provides the background on why the break up of these ice sheets is so shocking. They were strong, typically 100 feet thick up to about 350 feet thick, very old, and very stable.

Arctic ice shelves, old and thick, are relatively rare. They are markedly different than sea ice, which is typically less than a few metres thick and survives up to several years. Canada has the most extensive ice shelves in the Arctic along the northern coast of Ellesmere Island. These floating ice masses are typically 40 metres thick (equivalent to a 10-storey building), but can be as much as 100 metres thick. They thickened over time via snow and sea ice accumulation, along with glacier inflow in certain places, and are thought to have been in place over most of the past several thousand years .

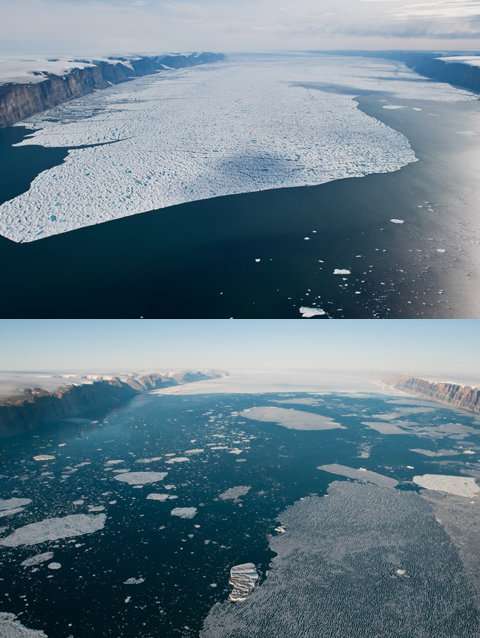

The ice sheets of Greenland are also breaking up.

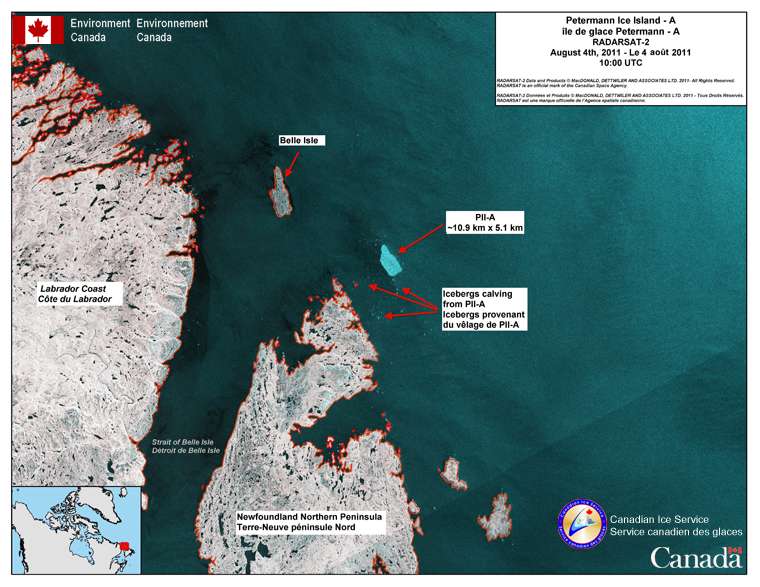

The Peterman ice sheet failed spectacularly several years ago producing an ice island, which is now about the size of Manhattan island, that has drifted to the coast of Newfoundland, Canada.

An aerial view of the Petermann glacier front taken on Aug. 5, 2009, top, and another taken two years later, on July 24, 2011.