When last we looked at Libya, American sails were disappearing over the horizon, leaving a bunch of shattered pirate egos in their wake – but that shouldn't be the only lesson we take from North African history. The rest of the 1800s will caution us that ignoring imperial conquests is not a good idea (see Afghanistan), while the 1900s show clearly the effects of ill-considered adventurism and treasure-sucking desert warfare.

So join your resident historiorantologist, if you will, in the Cave of the Moonbat, where the sun is setting on one set of empires and vassals, and beginning to rise on another. Keep your eyes peeled – you just might catch a glimpse of one of those new Sherman tanks Monty has been waiting for, or maybe a bunch of retreating Panzers.

Historiorant: Like all the Libya series, this diary goes out to Meteor Blades the Great and his family. The Sage knows why. ;-)

Earlier pieces to this great puzzle we call Libya:

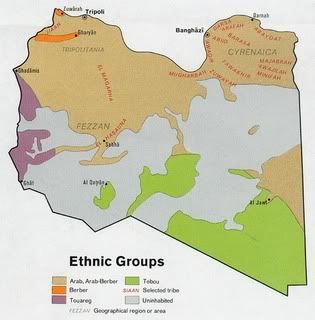

And a map, to refresh your memory as to the relative locations of Tripolitania, Cyrenaica, and the Fezzan – or do you think you're ready for the test right now? ;-)

Giants in the Earth

The last time we gathered in the Cave for a Libya-rant, we left off with ships flying the stars and stripes victoriously pummeling the fortifications of the Barbary Coast. American presidents of a caliber we simply haven't seen for a while had stood up to pirates who really were presenting a clear and present danger to U.S. interests, and in the process broke a centuries-old conviction in Europe that it's better to take the "pay tribute" option when dealing with Barbary corsairs. Nascent American sea power – and some daring footwork by William Eaton and a handful of US Marines – had exposed the weakness of the once-fearsome pirate states, as well as the fact the Ottomans weren't bothering (or weren't strong enough) to defend the outer reaches of the empire they claimed.

Jefferson and Madison waged their Barbary wars against a European backdrop rife with Napoleonic discord. After Trafalgar (1805), the French weren't going to be taking on anybody's navy, so Napoleon simply continued paying tribute to buy protection from the coastal lords, but when he met literally met his Waterloo in 1815, European governments began following the American model and started just saying "no" to pirate payments. This, of course, wrecked the economies of the Barbary States, dependent as they were upon a steady flow of protection money. The cash flow had been quite considerable: In 1799, the US alone arranged for an annual sum of $18,000 to buy off Tripoli, and about the same for the pashas of Morocco, Tunis, and Algeria. This was at a time when the Navy's budget of over $3 million was the highest it had ever been.

When you live by extortion, you tend to die by extortion; such was the case with the corsair hold on Libya. Once the pirates were shown to no longer be the threat they had been back in the 1600s, the Euro-powers quickly turned the tables on them. Britain and France threatened to invade Tripoli to secure the repayment of debts incurred when the pasha, Yusuf (the same guy who had been Eaton and Hamet's enemy, and Jefferson's "friend," back in 1804), began borrowing from European creditors after the protection racket dried up. In one of those crazily-predictable cause-and-effect things, the Divan (Ottoman viceroy) authorized an extraordinary tax to repay the debt, Yusuf implemented it, and the people rose up against its crushing burden. By the early 1830s, the nation was engulfed in civil war, and in 1832, Yusuf abdicated in favor of his son Ali – who, it turned out, followed that general dynastic rule about the son sucking worse than his father ever did, regardless of how badly the father had sucked as a leader.

Ottomans as Overlords: A Primer for Neocon Colonial Governance

Fortunately, in Ali's world there were adults who could step in and move to correct the situation. In 1835, he appealed to the Ottoman sultan for assistance, and Constantinople complied – to a point. Ali had expected some military assistance to prop up his own claim to the throne when the Ottoman ships appeared near Tripoli; he was likely quite surprised when the Turks took the more expedient course of packing him onto a naval vessel and sailing him off into exile.

Historiorant: Alas! Were it that The Decider fell under the jurisdiction of Cenk-like Turks, and an Ottoman navy would come to our nation's rescue!

Ottoman government was one of those things that looked a lot better on paper than it worked on the ground. The LoC Countrystudy has one of the more succinct descriptions:

The administrative system imposed by the Turks was typical of that found elsewhere in the Ottoman Empire. Tripolitania, as all three historic regions were collectively designated, became a Turkish vilayet (province) under a wali (governor general) appointed by the sultan. The province was composed of four sanjaks (subprovinces), each administered by a mutasarrif (lieutenant governor) responsible to the governor general. These subprovinces were each divided into about fifteen districts.

Executive officers from the governor general downward were Turks. The mutasarrif was in some cases assisted by an advisory council and, at the lower levels, Turkish officials relied on aid and counsel from the tribal shaykhs. Administrative districts below the subprovincial level corresponded to the tribal areas that remained the focus of the Arabs' identification.

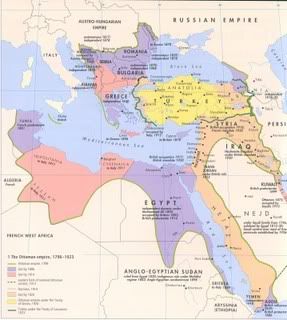

The Turks made a few half-hearted attempts to stimulate agriculture, but they couldn't really overcome that fact that they were well into the "decline & fall" phase of their empire. They did shuffle the administrative deck a couple of times – Cyrenaica was split off from Tripolitania in 1879, and after the government reforms of 1908 both regions had their own representatives in parliament. Still, the Ottomans never attempted to exert control very far inland; the Fezzan and the interior of Cyrenaica remained under the tribes, and their political philosophy was profoundly neocon-ish. As LoC so delicately puts it:

in general, nineteenth-century Ottoman rule was characterized by corruption, revolt, and repression. The region was a backwater province in a decaying empire that had been dubbed the "sick man of Europe."

And You Thought Sanusi Was a Brand of Japanese TV

When the leaders don't lead, the people start following those who will. To make things worse for the nearly-Commander-guyish incompetence of the Ottomans, North Africa has a peculiar tradition – probably with pagan origins, since Herodotus mentions them – of personal mystics known as marabouts. Limited pretty much to the Maghrib and West Africa (ie, wherever there's Berbers), some marabouts nonetheless gathered fervent (if localized) followings, established towns and cities, arbitrated political disputes, and, occasionally, were venerated as saints.

Such was the case with named Muhammad ibn Ali as Sanusi, an Algerian with Sufi roots who had gained such a prominent reputation as a marabout that by 1830, as he made his way toward Mecca, he was honored as as Sanusi al Kabir (the "Grand Sanusi") by the towns and tribes of Tripolitania and the Fezzan. Like other Muslim movements of the time, he preached a conservative message of austerity and a return to an earlier sense of morality, but this didn't mean voluntary poverty or Sufi-type spiritual aids: adherents were expected to earn their keep through work, weren't allowed to use stimulants, and were forbade traditionally Sufi practices like ecstatic dance. To quote LoC yet again, "The Grand Sanusi accepted neither the wholly intuitive ways described by the Sufis mystics nor the rationality of the orthodox ulama; rather, he attempted to adapt from both."

He tried to move the message to Mecca through the founding of a lodge there in 1837, but was run out of town a few years later due to disagreements with the Turkish rulers. He then discovered that, in the meantime, France had begun using its brand-spanking new Foreign Legion to conquer Algeria, and so the Grand Sanusi was forced to hang out his new shingle in Libya – specifically in al-Bayda, Cyrenaica, in 1843. From there, he presided over a movement that rapidly gained followers among the Bedouin tribes, where the tradition of marabouts saw Sanusi al Kabir venerated as something akin to a saint even within his lifetime, and saw the expansion of his movement to a new base at al Jaghbub, astride the caravan route to the Sudan.

The Grand Sanusi sprung the mortal coil in 1859, passing the reins on to his grandson, Muhammad. He quickly moved the Sanusi capitol further south, so as to confront French ambitions in the Sudan, and through his outstanding leadership and organizational skills became so admired that he was termed "Mahdi" ("guided one;" a prophesied redeemer of Islam). He is not to be confused with the Mahdi who later gave the British the Baghdad treatment in Khartoum – Islam in the 1800s saw several claimants to the title – but he did proclaim jihad to stymie French ambitions to Libya's south, and so became the first Sanusi leader to come into direct conflict with a European power. By the time of his death in 1902, the Mahdi had united the tribes of Cyrenaica in a way that no other leader could have; a string of 146 lodges stretched across North Africa and into Arabia and the roots of a nationalist movement had been laid before the Mahdi's cousin, Muhammad Idris as Sanusi (later King Idris of Libya), came to power – though a regency run by Ahmad as Sharif on behalf of the still-too-young leader picked a disastrous fight with the French that resulted in many lodges being destroyed.

A Late Starter in the Colony Game

While the French had spent the better part of the 1800s conquering and "pacifying" much of North Africa (including, to Italy's consternation, the area around Tunis), the Italians were still trying to get their domestic poop in a group. So it was that while the United States was descending into civil war only four score and five years after its founding, Italy was unifying into a single political entity – and when Garibaldi, Emanuel, and Cavour were finished with their nation-building, the newly-minted country eagerly jumped into the colony game in which the other Euro-powers had been engaging since the early 16th century. Seeing North Africa as a logical foothold, the Italians set their sights on Libya.

Britain and France were aware of Italian interest in Libya as far back as the 1878 Congress of Berlin, where it had been decided that the Ottomans wouldn't be able to do anything about it if England took over control of Cyprus, and France Tunisia. Ever wanting to stick it to the Turks, the French conducted a secret treaty with Italy in 1902 that recognized Tripolitania as liable to Italian intervention in exchange for Italian of France in its ongoing Moroccan Crises with Germany. The Italians tucked away the permission slip for another 9 years.

Even George W. Bush recognized that if you want to wage an aggressive war against a country that hasn't actually done anything to yours, you have to engineer a crisis. Voila! In September, 1911, Italy charged the Ottomans with arming (curiously, the accusation didn't include anything about weapons of mass destruction) Arab tribesmen in Libya, and that this constituted a "hostile act." Italy further stated that the only possible solution was Italian military occupation of the territory, and they issued an ultimatum to that effect. Because this was the early 20th century, and countries still went to war over trumped-up, stupid reasons, Italy declared war and invaded when Constantinople failed to reply.

"A military walk"

The summer of 1911 saw a yellow-press-like fanning of the war flames in Italy. Libya was described as a place where the main problem in extracting the vast mineral wealth was dredging it out of the abundant water. Furthermore, it was a ripe target for Italy's modern military machine, since it was defended by only 4000 or so Turkish troops (the estimate of Ottoman strength was probably a little light, and didn't include tribal allies, but was mostly accurate), and the locals were said to be groaning under the yoke of Turkish oppression to such an extent that they would welcome the Italians – who they naturally liked – as liberators. The entire operation was to be "a military walk" that would showcase Italian prowess at arms and the ability to bully on an international scale.

Weird Historical Sidenote: I'll avoid the temptation to make a few pointed observations about Italy in 1911 and the US in 1898/2002, and just mention the future fascist dictator Benito Mussolini, at this time still a leftist like his daddy (who'd named him after Mexican man-of-the-people Benito Juarez) had wanted, took a strong public stance against aggressive war with the Ottomans over Libya.

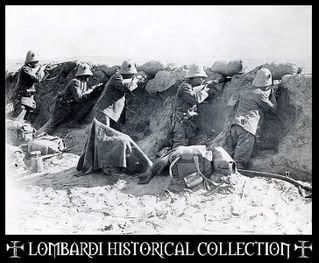

After a short naval bombardment, Tripoli fell to 1500 Italian sailors on October 3, 1911. In short order, Italian forces had also taken Tobruk, al-Khums, and Darnah (Bill Eaton's old stomping grounds), but ran into stiffer resistance at Benghazi. On October 23, an expeditionary force of around 20,000 men was almost surrounded and came quite close to being annihilated by Arab cavalry and a few Turkish regulars near Tripoli, but though the event was described in the Italian press as a small revolt, it resulted in a surge of nearly 100,000 soldiers to fight the 20,000 or so Arabs and 8000 Turks who had withdrawn to the provinces to conduct their resistance. Among the Turks were future world-class leaders Enver Pasha and Mustafa Kamal Ataturk, who led a vigorous, quasi-religious defense against the Italian expeditionary force sent against them. The moves toward the interior failed, and Italy never did secure much more than a thin beachhead stretching from Tipolitania to Cyrenaica.

Though it lasted only a year – and "major combat operations" were pretty much taken care of in the first two months – the Italo-Turkish War was a critical precursor of the First World War in a number of ways. In the short run, nationalist types in the Balkans awoke to the realization of just how big a pushover the Sick Man of Europe had become, and started launching independence wars of their own in late 1912. The feelings engendered during this set of Balkan Wars led to the rise of groups like The Black Hand, who most famous member, 19-year-old Gravilo Princip, would fatally (and fatefully) shoot Austro-Hungarian Archduk Franz Ferdinand two years later.

The other foreshadowings were technological: trenches and machine guns played a menacing part, and aircraft – only 8 years off the theoretical drawing board – were used for reconnaissance and bombing. In fact, the very first bomb known to have been deployed from an aircraft in combat was dropped by the Italians on Turkish positions on November 1, 1911 – giving Libya the dubious distinction of being the first country ever to be aerially bombed.

The other foreshadowings were technological: trenches and machine guns played a menacing part, and aircraft – only 8 years off the theoretical drawing board – were used for reconnaissance and bombing. In fact, the very first bomb known to have been deployed from an aircraft in combat was dropped by the Italians on Turkish positions on November 1, 1911 – giving Libya the dubious distinction of being the first country ever to be aerially bombed.

World War in Libya, Part I

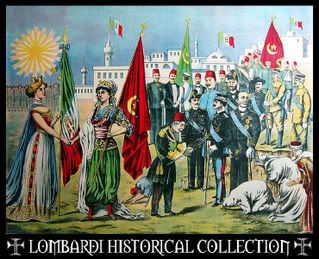

With war clouds gathering in the Balkans, Italy was able to press the Turks into cutting their losses with a peace deal. In truth, Rome wasn't being entirely altruistic; the war was costing more than double the initial estimated price tag of 30 million lira per month, and was taking twice as long as promised, too. Still, in the Treaty of Lausanne, signed in October, 1912, the Ottomans agreed to give up suzerainty of its Tripolitanian and Cyrenaican holdings – though its independence was to last only as long as it took the treaty-reader to scan down a couple of lines, where Italy annexes the newly-up-for-grabs state of Libya. This did not site well in the Islamic world:

For many Arabs, Turkey's surrender in Libya was a betrayal of Muslim interests to the infidels. The 1912 Treaty of Lausanne was meaningless to the beduin tribesmen who continued their war against the Italians, in some areas with the aid of Turkish troops left behind in the withdrawal. Fighting in Cyrenaica was conducted by Sanusi units under Ahmad ash Sharif, whose followers in Fezzan and southern Tripolitania prevented Italian consolidation in those areas as well. Lacking the unity imposed by the Sanusis, resistance in northern Tripolitania was isolated, and tribal rivalries made it less effective. Urban nationalists in Tripoli theorized about the possibility of establishing a Tripolitanian republic, perhaps associated with Italy, while Suleiman Baruni, a Berber and a former member of the Turkish parliament, proclaimed an independent but short-lived Berber state in the Gharyan region. For the beduins, however, unencumbered by any sense of nationhood, the purpose of the struggle against the colonial power was defending Islam and the free life they had always enjoyed in their tribal territory.

LoC Countrystudy

The cagey Ottomans, true to their Byzantine inheritance, made themselves a thorn in Itlay's side by negotiating into the document a provision in the treaty that allowed them to appoint the Qadi (religious judge) in Tripoli. This put a Muslim in charge of the sharia courts, and given the lack of distinction between civil and religious codes under sharia jurisprudence, Italian administrators often found themselves civilly disadvantaged by a lack of control over the judicial system. It also gave them in inroad to fighting the Italians in a repeat engagement, should the opportunity arise.

It did, of course, in 1915, when Italy cast its lot against the Central Powers, of which Ottoman Turkey was a member. In April of that year, Sanusi rebels (who had launched the First Italo-Sanusi War the year before) captured a large stockpile of munitions from an Italian column they ambushed, and went on an offensive that served to tie down British and Italian soldiers who would have better served their countries in France and Austria. Turkey and Germany supported this effort with arms shipments to the Sanusis, but wound up doing them wrong in 1916, when Turkish officers led Sanusi troops on a disastrous invasion of British-held Egypt. As a result, on-again, off-again general Ahmad ash Sharif had over control once and for all to Idris (for whom he had long served as regent/overbearing advisor) boarded a German submarine and fled into exile in Turkey.

Idris was far more pro-British than his predecessor Sanusi leaders, and he cut a deal with them in 1917. He was recognized as the amir of interior Cyrenaica (he had to promise to stop raiding Egypt and the coastal towns), and under an incoherent Italian policy for the administration of their Libyan colony had a great deal of sway in the government and control of every oases in eastern Libya. The Italians were forced into no such concessions in Tripolitania, however, where rival factions with fundamentally different objectives – urban Arab and Turkish nationalists vs. Bedouin tribesmen – were infighting to the point that the Italians didn't have to do much to divide and conquer.

The King and the Fascists

By 1922, things had gotten to the point that the nationalists felt they had no choice but to turn to the one guy who had successfully dealt with the Italians: Idris. They asked him to assume the amirate of Tripoli, knowing full well that the Italians would see the move for what it was: an attempt at nationalist unification within one of their Treaty of Versailles-ordained colonies. The Italians would fight; this is the main reason Idris retreated into Egypt after his November announcement that he'd take the job, but he probably didn't foresee the enormous shift in colonial policy that would occur as a result of events in Rome the month before – it was in October, 1922, that Mussolini and his black-shirted fascists marched into the capitol and bullied control from the king.

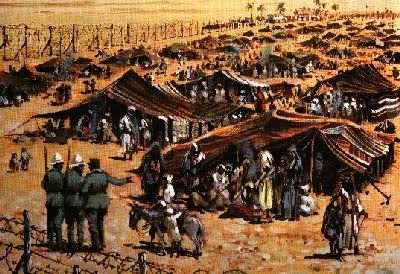

The Second Italo-Sanusi War, which transpired while the United States was dancing the Charleston, not drinking (wink, wink), and buying stocks on margin, and Europe was watching the Weimer Republic run itself into the ground, was a no-holds-barred pacification offensive that began in early 1923, when the Italians marched on Sanusi positions in Cyrenaica. For nearly a decade the Sanusis resisted a brutal campaign of repression by the fascists (actually, they were mostly Eritrean troops) under Generals Pietro Badoglio and Rodolfo Graziani, who utilized concentration camps, 320-km fences of barbed wire, tanks and aircraft, and a policy of public execution and group reprisals to whittle away at Sanusi numbers through bloody attrition.

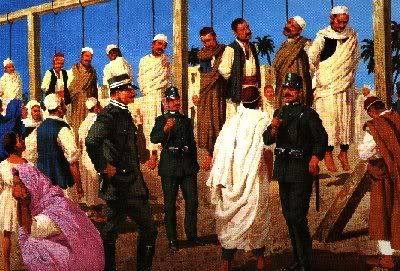

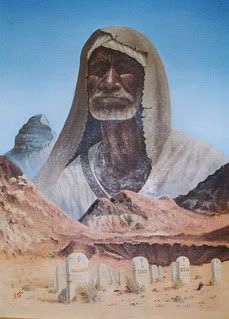

Such times often give rise to national heroes, and this was no exception for Libya. An aged desert fighter, Umar al Mukhtar, had been left in command of the Sanusi forces, and he used them in a brilliant campaign of guerilla tactics and daring raids despite his ever-dwindling numbers. Not unlike the Native Americans of a few decades before, the Sansusis made the enemy pay for every inch of advance, but in the end were overwhelmed by their foe's inexhaustible numbers and technological might. What resistance there was effectively collapsed with the capture and execution of Umar al Mukhtar on September 15, 1931 – an event the Italian authorities compelled 20,000 Arabs to witness. Mukhtar's stand, and Mukhtar himself, were revered around the Arab world as symbols of resistance, and are still held in very high regard in Libya today.

The Politics of Colonies and Dissident Exiles

The 1930s saw Mussolini strengthen his hold on the territories – he's the one who resurrected "Libya," a term used by Diocletian 1500 years before, as a political designation – by launching an aggressive campaign of modernization and land reform (of the type that only favors the colonialist) and promoting emigration. By the outbreak of the Second World War, upwards of 12% of the Libyan population consisted of recent Italian immigrants, and these were supported by a governmental structure that seriously favored the colonizers, such as replanting orchards with olive groves and putting traditional grazing lands under the plow. Infrastructure improvements in education, etc., never quite made it down to the Bedouin level, and all administrative posts, at all levels, went to Italians – prior arrangements regarding input from local chieftains be damned. Finally, it was under Mussolini that the modern borders of Libya took shape, as he negotiated through the 1930s with Britain and France, and he continued to actively suppress Sansusis as a rearguard action against possible revolt.

The hopes of Libyan nationalists were pinned to Italy's fortunes – they realized they would never gain independence without Italy's defeat in a larger conflict. Their hopes for an international smackdown of fascist ambitions rose briefly in 1935, when Haile Selassie of Ethiopia called the League of Nations of the carpet in the face of Italian invasion, but those hopes fell again when the League wussed out and did that head-in-the-sand/Republicanesque-foreign-policy thing that it was so good at. So it was that the leaders of the Tripolitanian nationalists and the Cyrenaican Sanusis, gathering in Cairo as war enveloped Europe in 1940, waited to see what Italy was going to do before they declared support for anyone. Here's kind of how the arguments went:

- Cyrenaican leaders – had been in secret contact with Brits for months; publicly declared their own support without waiting for Tripolitanian blessing

- Tripolitanian nationalists – feared reprisals if Britain lost, which seemed entirely plausible in the summer of 1940.

- Idris – if the Brits did win, they wouldn't be much inclined to recognize the independence of a people that failed to help them in the midst of the war

In the end, Idris' argument persuaded them, but there were significant unresolved suspicions between the Tripolitanians and the Sanusis the next several years regarding one another's intent vis-à-vis the British and independence. The agreement arrived at between Libyan leaders in exile and the British military in Cairo in August, 1940, did much to look out for Cyrenaican interests, but fell short of the independence language the nationalists were trying to hold out for.

World War in Libya, Part II

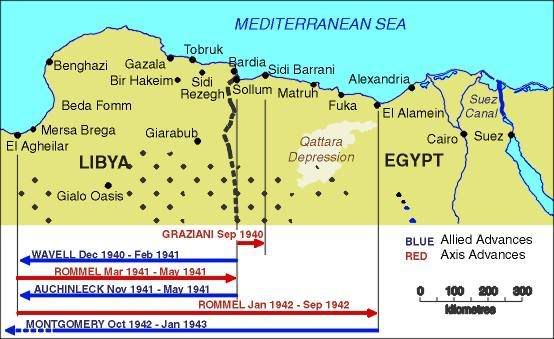

As things turned out, it was Cyrenaica that saw the brunt of the fighting during the North African campaign, beginning with the September, 1940, Italian invasion of Egypt. The offensive stalled at Sidi Barrani, and in early December, General Archibald Wavell counterattacked with his Army of the Nile, advancing as far as Tobruk by the end of the year. By February, Wavell had maneuvered his 2 divisions to the point where 10 Italian divisions (consisting of 150,000 men) were forced to surrender, meaning that if the Nazis really wanted to control the Suez Canal and the quick routes to the oil fields, they were going to have to come in and get it themselves.

As things turned out, it was Cyrenaica that saw the brunt of the fighting during the North African campaign, beginning with the September, 1940, Italian invasion of Egypt. The offensive stalled at Sidi Barrani, and in early December, General Archibald Wavell counterattacked with his Army of the Nile, advancing as far as Tobruk by the end of the year. By February, Wavell had maneuvered his 2 divisions to the point where 10 Italian divisions (consisting of 150,000 men) were forced to surrender, meaning that if the Nazis really wanted to control the Suez Canal and the quick routes to the oil fields, they were going to have to come in and get it themselves.

The Afrika Korps and its Desert Fox of a commander arrived in March and April, 1941, and quickly launched an offensive in Cyrenaica that cut off the garrison at Tobruk – an Australian force that became known as the "Rats of Tobruk" after Lord Haw Haw, the Nazi version of Tokyo Rose, disdainfully referred to them as rats in a trap – which held out against a seven-month siege while Rommel strove to stabilize his lines further east preparatory to an all-out assault on Egypt. In November, 8th Army commander General Claude Auchinleck punched through the German lines to relieve Tobruk, and in so doing compelled Rommel to withdraw from the Egyptian frontier. At Al Agheila, his army refitted for an offensive launched in January, 1942, which blazed across Cyrenaica and placed Tobruk – object of so much see-sawing only a few months before – back in Nazi hands in only a single day. All of Cyrenaica was under Axis control by June, and by September, the Nazi army was at El Alamein, only 60 miles from Alexandria.

The Afrika Korps and its Desert Fox of a commander arrived in March and April, 1941, and quickly launched an offensive in Cyrenaica that cut off the garrison at Tobruk – an Australian force that became known as the "Rats of Tobruk" after Lord Haw Haw, the Nazi version of Tokyo Rose, disdainfully referred to them as rats in a trap – which held out against a seven-month siege while Rommel strove to stabilize his lines further east preparatory to an all-out assault on Egypt. In November, 8th Army commander General Claude Auchinleck punched through the German lines to relieve Tobruk, and in so doing compelled Rommel to withdraw from the Egyptian frontier. At Al Agheila, his army refitted for an offensive launched in January, 1942, which blazed across Cyrenaica and placed Tobruk – object of so much see-sawing only a few months before – back in Nazi hands in only a single day. All of Cyrenaica was under Axis control by June, and by September, the Nazi army was at El Alamein, only 60 miles from Alexandria.

Here, taking advantage of a natural bottleneck created by geography, General Bernard "quick as a ferret and about as likeable" Montgomery (with whom Churchill had replaced Auchinleck, who was regarded as a bit on the incompetent side by his troops) made his stand. Using air superiority and good intelligence, he had been able to slow Rommel's advance by choking off his logistical lifelines, and during fierce fighting around El Alamein in late August, was able to hold the line and compel the Germans to move off to await reinforcements and supplies. Like Meade after Gettysburg, Monty failed to pursue the withdrawing Germans, opting to further stockpile munitions for a counterattack he didn't launch until October 23.

Operation Lightfoot, Monty's initial strategery, involved infantry "light-footing" it over anti-tank mines, then clearing them by hand while the tanks followed behind in a massive, one-night elephant walk. It was a dumb plan, and it failed, though it did kill many Germans – including the guy Rommel had left in command while he was on sick leave in Austria; General George Stumme died of a heart attack while undergoing a 900-gun bombardment by the British (the largest since the Great War). Monty's next, Operation Supercharge, he launched on November 1, continued the deadly attrition begun by Lightfoot – Rommel, still weakened from illness and arriving upon a chaotic scene, lost half his 100,000-man army before it was all over – and in the end, it broke Germany's ambitions in North Africa. The Desert Fox learned of the American landings in Morocco and Algeria on November 8th; from that point on, he was on the defensive throughout the Maghrib. Despite inflicting heavy losses on green American troops at the Battle of Kasserine Pass in Tunisia, by March, 1943, Rommel was being recalled to Germany and the fate of the now-shattered Afrika Korps was left to Hans-Jurgin von Arnim, who wound up being the guy who surrendered 275,000 Axis troops to the Allies in May.

Apres la Guerre

The British and French split up the duties of administering the conquered territory for the remainder of the war, but while the Brits were training a badly-needed core group of civil servants, the French were arousing suspicion by doing sneaky territorial things in the south, along the borders with Chad and such. The Allies decided at Potsdam that Italy would not be getting its colonies back, so it fell to the United Nations to try to sort things out after the war ended – and as with all things UN-ish, it took time. It didn't help that Libya was considered economically worthless; even its sand was unsuitable for glassmaking, and its biggest export in the post-war years was scrap metal from all the battlefields. Politically, the allies debated who would get to administer which region and for how long, and Idris, with British backing, re-established his claims to control of a vaguely-autonomous Cyrenaica in 1949. To turn to LoC once again:

Many groups vied for influence over the people but, although all parties desired independence, there was no consensus as to what form of government was to be established. The social basis of political organization varied from region to region. In Cyrenaica and Fezzan, the tribe was the chief focus of social identification, even in an urban context. Idris had wide appeal in the former as head of the Sanusi order, while in the latter the Sayf an Nasr clan commanded a following as paramount tribal chieftains. In Tripolitania, by contrast, loyalty that in a social context was reserved largely to the family and kinship group could be transferred more easily to a political party and its leader. Tripolitanians, following the lead of Bashir as Sadawi's National Congress Party, pressed for a republican form of government in a unitary state.

ibid.

By late 1951, a power-sharing arrangement was reached in which a federal system was set up under a monarchy, the throne of which was offered to Idris. On December 24, 1951, he proclaimed the independence of the sovereign United Kingdom of Libya.

Historiorant:

And that's gonna hafta do it for tonight's episode – 10 pages already, and still a Qadaffi to go. Tune in next week – same bat-channels, approximately the same bat-time – for the conclusion of this four-part ode to yet another country that I didn't know anything about. See you at the oil fields of Beghazi, or maybe along some Line of Death in the Gulf of Sidra.

Historically hip entrances to the Cave of the Moonbat can be found at Daily Kos, Progressive Historians, Never In Our Names, and The Impeach Project

CYA

Hangings and Concentration Camp images via intellnet.org/Black Day

Other images via Wikipedia Commons

Killer WWII campaign map via diggerhistory.info

Other maps per citation in Ancient Libya