A week ago, Barack Obama led Hillary Clinton by 10 points in the Gallup Daily Tracking Poll. I asked the readers at fivethirtyeight.com whether they expected today's poll -- it's April 6th -- to show a lead of greater than 10 points for Obama, or fewer.

I was sort of trying to goad people into taking the over. After all, we're all used to hearing about the importance of "momentum" and trendlines. Obama had gone, over the span of about 10 days, from being 7 points behind, to roughly tied, to 4 points ahead, to 10 points ahead. Wasn't it logical that he'd be some number larger than 10 points ahead after another week's worth of "momentum"? Wasn't the headline that Obama was pulling away with the race?

But most people did not take the bait, and said they expected Obama to be fewer than 10 points ahead. Which, as it turns out, was the right answer. In today's Gallup Tracker, Obama is 3 points ahead of Hillary Clinton:

Most people who took the under cited the principle of "regression to the mean". And this is an underrated dynamic in analyzing polls. Ninety-five percent of polls, theoretically, fall within the margin of error established by the pollster. The flip side to that is that 5 percent don't.

Five percent -- one out of 20 polls -- doesn't sound like a lot. But consider how many polls come across the wire in a given week. Rasmussen and Gallup each release three tracking polls per day, seven days per week: an Obama-Clinton primary tracker, and general election trackers for both Obama-McCain and Clinton-McCain. That's (7 x 3 x 2 =) 42 polling results right there. Beyond that, we're averaging about 15 new state-by-state general election polls each week. Those polls are surveying two matchups each (Clinton-McCain and Obama-McCain), so that's another 30 contests. On top of that, we might have another 10 or 15 primary election polls in states like Pennsylvania or Indiana, and two or three of the "name brand" national pollsters like CBS/NYT or Pew will weigh in each week with their periodic updates.

So in a given week, we're probably looking at somewhere between 75 and 100 polling results. (By my count, there have been 86 different Presidential election-related polls released publicly since last Monday). Not only might some of these polls be "wrong" (that is, fall outside their margin of error). Some of them will be wrong. It's a mathematical certainty. We should expect to see four or five "bad" polls each week. And that's assuming that the pollsters are doing everything perfectly, which they aren't (not by a long shot).

Of course, it can be a dangerous game to try and guess which polls are the outliers and which ones aren't. A lot of people believed that the Selzer/DMR New Years' Eve Iowa poll was an outlier -- but it turned out to be just about the only one that predicted the Iowa caucus results correctly.

Before Iowa, however, the behavior of the polls was quite volatile. The dynamics of the campaign were changing on a day-to-day basis. Moreover, the pollsters were forced to poll during the Christmas/New Years Holiday, a period they've generally avoided, and nobody had any idea how to model turnout, with no voting yet having been conducted.

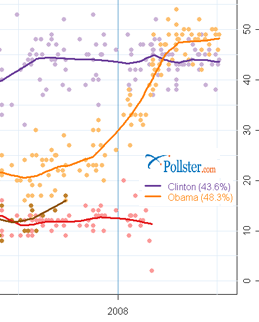

The polls remained quite volatile up through and including Super Tuesday. At some point in the middle of February, however, the polls fell into something of a steady state. Obama took the lead from Clinton in the Real Clear Politics average on roughly February 10th. He has held on to that lead ever since. But he has never held a particularly large lead. It's essentially always been somewhere between 1 point, and 6 or 7 points -- sometimes toward the top of that range, and sometimes toward the bottom, but always between those goalposts. This becomes even more clear when looking at the Pollster.com averages, which tend to smooth out some of the day-to-day fluctuations in the polls.

Pollster.com has Obama's numbers moving up steadily up through about the 15th of February. And then they plateau. They don't peak -- they don't go down any -- they just plateau. The same is true for Hillary Clinton's numbers. In fact, Clinton has been stuck at about the same level of support, somewhere in the 42-46% range, since Labor Day.

Now, it's a truism that primary polls are generally more volatile than general election polls. In fact, they are often much more volatile. If we tried to apply the fivethirtyeight.com model, which is designed to predict general election outcomes, to predict primary results instead, it might well lead us in completely the wrong direction (among other things, we'd need to place much more of a premium on recentness if we were trying to evaluate the primaries).

But there are specific reasons why primary polls tend to volatile -- and I would argue that those reasons no longer really apply in the Democratic nomination race:

- In the primaries, voters generally have weak preferences between the two candidates. After all, you are asking voters to choose from among two or more candidates in their own party. Many voters will have a favorable impression of all of these candidates. That means, however, that it doesn't take much to move a voter from one candidate to the other.

- In the primaries, voters generally have limited information about the candidates. Presidential candidates usually come from the ranks of the nation's 150 U.S. senators and governors. Even relatively well-informed voters aren't keeping tabs on most of these elected officials; in fact, they'd probably have trouble naming more than 20 or 30 of them. So a significant element of the primary process is simply voters becoming better informed about the candidates and their positions, and the polls can be quite volatile until that process is complete.

Neither of these axioms really hold any longer for Senators Clinton and Obama. Each candidate has nearly 100% name recognition (this has been true for a long time for Hillary, of course). They have been campaigning for more than a year. They have poured a collective $250 million dollars into the campaign, and probably gotten well upwards of a billion dollars apiece in terms of free media exposure. Voters know Clinton and Obama inside and out. They aren't really learning anything new about them -- and for that matter, Clinton and Obama aren't even really bothering to talk about policy these days (instead, all of the discussion is about the metaphysics of the nomination process).

Moreover, preferences between the two candidates have hardened. Both candidates have experienced some recent deterioration in their favorability/unfavorability ratings (see charts below). Although we don't necessarily know how much of this is Democrats turning against their own candidates, versus independents and Republicans being turned off, the general anecdotal sentiment I pick up among Democrats these days is "Don't you get it? We've made up our minds. We're just waiting for this to end". People are bored, and people don't change their votes when they're bored.

This is not to say that there is never any day-to-day movement in the polls. Clearly, for instance, the Jeremiah Wright controversy depressed Obama's numbers for a period of 7-10 days. But the polls fell back into equilibrium pretty quickly. And other events, like Hillary's big victory in Ohio on March 4 -- or, for that matter, Barack Obama's win in Wisconsin -- didn't seem to have moved the polls at all.

But what about Obama's recent upward movement in North Carolina and Pennsylvania? Doesn't he have momentum there?

Well, his numbers have certainly improved in those states. (Although, it partly depends on where you start measuring from; Obama had closed to within 4 points of Clinton in a Rasmussen poll of Pennsylvania on 2/26.) But I don't know that I'd really call it momentum, which I tend to think of as a sequential process in which one result favorably affects the next. It's not like Obama's moving up in Pennsylvania because he won Wyoming three weeks ago.

Instead, what I think we're seeing in Pennsylvania and North Carolina is something different: organization and ground game. Obama's numbers have moved upward in the last few weeks before the primary in essentially every single state that he's campaigned in. But this movement has been local rather than national (otherwise he really would have the nomination wrapped up by now). It seems to me that Obama has some systematic advantages on the ground, including some combination of the following:

- Higher density of advertising, and/or more effective advertising.

- Higher concentration of field offices and/or superior outreach efforts and/or greater enthusiasm from paid and unpaid volunteers.

- Better attended and/or better staged and/or more persuasive campaign events.

- Superior handling and/or more favorable treatment from local media (consider his substantial advantage in newspaper endorsements).

- Possibly, superior data mining and microtargeting (this last one is pure speculation on my part, as it's not something a campaign is ever going to want to talk about).

This is not to say that Sen. Clinton is a poor retail campaigner. On the contrary, I think she's an above-average one. She seems frankly to have more endurance than Obama, and her campaign has shown an ability to dictate the course of key media cycles, even if they do not necessarily win them. These assets may be particuarly valuable during the last 72 hours of the campaign. But, based on the almost predictable way in which Obama seems to improve his polling numbers in the T-minus 7-to-30 days period, as we're seeing in Pennsylvania now, we have to give some deference to Obama's ground game.

...

The interesting thing is that, even though the national polls haven't changed, the futures markets have.

Clinton's chances of winning the nomination are now trading at about 13%, which, incidentally, is just about where she was prior to the Texas and Ohio primaries. After shooting up to around 30% following her victories in those states, her stock has had a fairly linear progression back to that 13% level (interrupted by a couple of 'shocks': the market reacted strongly to the Jeremiah Wright story and the Bill Richardson endorsement).

There are, I think, three things that account for this. Firstly, the traders in these futures markets, many of whom are based offshore, are not all that insightful amount American politics. They tend to react too strongly to the media narrative of the day, and not strongly enough to the more glacial forces that really win and lose campaigns. (For example, the market moved a lot after a Clinton adviser told Politico she had no more than a 10 percent chance to win, a non-event that did not affect the fundamentals of the race at all). Secondly, there was a lot of "hidden" bad news for Clinton during this period, such as the continued decline in her superdelegate advantage, and the failure to secure revotes in Florida and Michigan.

However, there is something else going on too. In order for her to have a chance at winning the nomination, Clinton needs there to be volatility in public sentiment. Or, if you prefer, she needs there to be momentum. To get more specific about it, she needs the Pennsylvania result to impact the North Carolina and Indiana results. Otherwise, what will happen is something like this: Clinton will win Pennsylvania by about 6 points, then she will lose North Carolina by about 16 points, but win Indiana by about 7 points (these are the present polling averages in those states). By my math, that would result in a net swing of 3-4 delegates, and 25K-50K popular votes, to Obama between now and May 6th. Although the rest of the schedule would be nominally favorable to Clinton -- I show her picking up a net of 15-30 delegates after May 6th on the strength of big wins in West Virginia, Kentucky, and possibly Puerto Rico -- at that point the campaign would probably be over.

So the fact that the national polls have been stubbornly unmoving is almost as bad news for Clinton as if the polls were breaking away from her. At least if the polls were moving away from her -- that would indicate a volatile electorate. But instead, it's as though we're playing out the last couple of tricks in a euchre hand after the point has already been won. A lot of the value in the Clinton stock, back when it was trading at 30%, was in the possibility that something dramatic would happen. Every day that something doesn't happen is bad news for Clinton. By the way, if the Clinton campaign is reading these numbers the same way I am -- I would look for them to make news this week.

(cross-posted at fivethirtyeight.com)