It is almost universally received wisdom that when the turn comes, we will have a "jobless recovery" where GDP turns up anemically, but unemployment stubbornly rises, just like after the last two recessions. Indeed a couple of weeks ago I wrote about a structural change in the American economy, where primarily due to offshoring, it took 2% GDP growth just to generate a single net new American job.

While we still have that structural problem, there is mounting evidence that -- and I'm not saying it will happen, only that there is a surprisingly decent case to be made that it might -- contrary to the accepted wisdom, the recovery from this recession may not be "jobless" at all, but particularly in its earlier portion may feature quite robust job growth as the GDP starts to grow probably right now. This is the second of three diaries in which I examine that surprisingly strong case that this may not be a "jobless recovery" after all.

In Part I of this series, I looked at new jobless claims and compared them with unemployment data for the period of 5-14 weeks duration, which is still slightly leading, and also has less noise. Not only is that metric declining steeply (off 17.5%, just through the end of June), just as it did after the 1974-1982 recessions, and unlike the two "jobless recoveries", but because of auto plant closures and start-ups, it is almost certainly going to reported as having declined considerably further in July. This metric not only tells us not just that the recession is nearly over, but suggests that at least in the next few months, there could be actual job growth, more robustly than almost anyone suspects.

In this part, I look at the past history of steep declines in manufacturing. What I have found is that, in such cases, slack manufacturing employment has snapped back quickly in the subsequent recovery.

In the course of researching the relationship between declines in initial jobless claims and peaks in unemployment, I found that (1) in those recessions and recoveries where jobless claims fell steeply, peak unemployment occurred within 2 months of the point where jobless claims fell 12% from the peak; but (2) in those recessions and recoveries where jobless claims fell slowly, peak unemployment occurred not at the 12% mark, but only when new jobless claims were more than 16% less than peak claims, and stayed more than 16% off for at least 3 months thereafter. What was totally unexpected, was that in both the 1991 and 2001 recessions, as soon as the 16% marker was reached, the recovery in jobs stalled. Something was happening that was interfering with the hiring of more workers exactly at the point where new hiring, and plant expansion, should have kicked in. I suspected, and still do, that what was really happening was that once the economy began to pick up -- and only then -- employers took advantage of the situation not to hire more Americans, but instead to offshore jobs and plants to low wage countries.

Here's the chart, showing the year, and months from the peak in initial jobless claims that they retreated 12%, 16%, and the month of peak unemployment. In the case of the two "jobless recoveries" I also show the range from peak of initial jobless claims during the time of +GDP with increasing unemployment:

<tbody>| Year | Mo./-12% | Mo./-16% | Mo./peak

unemployment | range/

jobless claims |

|---|

| 1970-71 | 1/71 | 2/71 | 11/70 | n/a |

| 1974-75 | 5/75 | 7/75 | 5/75 | n/a |

| 1980 | 7/80 | 8/80 | 7/80 | n/a |

| 1982 | 10/82 | 11/82 | 12/82 | n/a |

| 1991-92 | 9/91 | 7/91, 6/92 | 6/92 | -8% to - 16% |

| 2001-03 | 12/01 | 2/02, 6/03 | 6/03 | -7% to -21% |

</tbody><tbody></tbody>

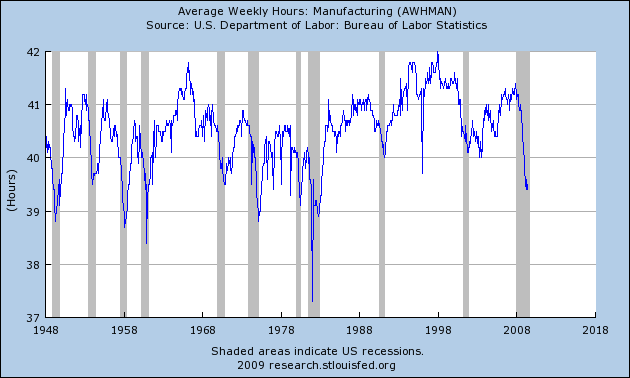

Clearly something different was happening at the end of the last two recessions -- which as I discussed previously, I strongly suspect was the offshoring of jobs. When I looked for a data point where it might show up , in the statistic for average weekly hours in manufacturing. I found that contrary to prior V-shaped job recoveries, in 1991-3 and 2001-3, hours worked in manufacturing were flat. Here's a graph of manufacturing hours since 1949 (not including July's data reported last week):

In general, over the entire time period of the last 60 years, the deeper the "V" in hours (i.e., more than a 1.5 hour decline, to a level below 39.5 hours), the quicker the snap-back in hours worked once the recession ended. (The one ambiguous case is the tepid hours recovery from the 1970 recession, during which time not only were the mass of baby boomers for the first time entering the full-time job market, but 500,000 of them were being withdrawn from Vietnam for an extra surge of workers.) In the above graph, the 1991 and 2001 recessions stand out like a sore thumb: In neither case did hours worked ever fall below 40! Once the recession ended, there was no slack to be picked up by rehiring laid off workers and increasing production at the plant. Instead, the offshoring (I hypothesize) began immediately. Thus, if past patterns are prologue, then what the graph of average hours worked in manufacturing argues is that at least over a substantial period thereafter, we will have a quick snap-back in hiring as opposed to a "jobless recovery."

That this recovery might indeed be different has recently been noticed by a few mainstream commentators as well. For example, investment site 'Clusterstock' noted that:

Bit by bit, the consensus of 'L-shaped, jobless recovery' is starting to crumble, as more and more are calling for a V-shaped comeback.

and cited the Wall Street Journal article indicating:

The rapid pace at which businesses shed jobs during the recession comes with a flip side: Workers will need to be hired back quickly as the economy improves.....

"Firms were unusually aggressive in cutting costs and cutting employment," said James O'Sullivan, an economist with UBS. "The flip side of that remains to be seen, but it could mean that companies will be quicker to bring back people because they were more aggressive about getting rid of them."

Businesses say they are running lean....

"I'm unaware of any firm out there today that has lots and lots of people sitting on the bench, waiting for business to come back," said Mr. Ballou. As a result, he thinks jobs will come back more quickly as the economy recovers than they did in 2001.

When I posted the first version of this diary at the Bonddad blog in late July, I concluded that one way to tell if we were going to have a V-shaped recovery or not would be "monthly manufacturing hours worked: an average rise of only 0.1 hours per month means a lackluster increase in plant use, over 0.15 supports a V-shaped recovery." Lo and behold, last week there was an abrupt and surprising rise of +0.3 in manufacturing hours in July. That is some initially strong evidence that a V-shaped jobs recovery might indeed take place.

Now that I have examined the manufacturing side of the issue, in Part III I will discuss the consumer demand side of the issue.