Despite the fact that most economic numbers are currently moving in the right direction, one statistic remains stubbornly high: the unemployment rate. The question on everybody's lips is when will this number come down? Let's look at the data to see what it says.

Let's begin with an analogy: if you have a heart attack on Monday, you won't run the marathon on Friday. To extrapolate this to economic terms, an economy is not going to experience several months of job losses above 600,000 and then show job growth within a few months; it's just not going to happen that way. And given the severity of the job losses earlier this year, it's more than likely we'll see at least nine months of bad numbers and probably longer. The reason is simple: an economy the size of the US' does not turn on a dime. It takes time to go from massive losses to gains. That's just the way it works.

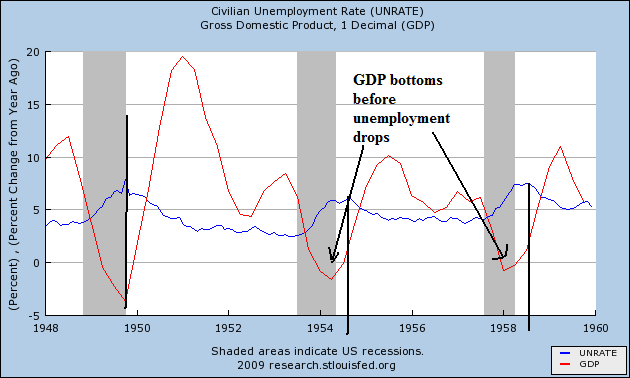

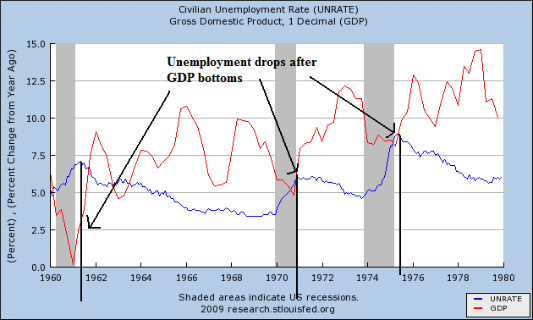

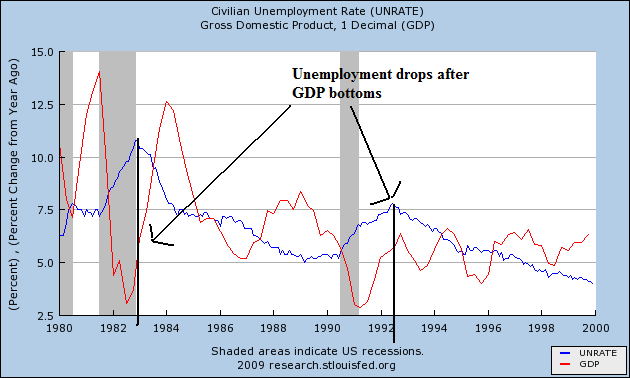

That being said, let's look at history to see when we should start to expect a drop in the unemployment rate. Below are three graphs that coordinate two data sets: the year over year percentage change in GDP and the unemployment rate. Each chart is broken down into smaller, more easily understood components -- the first is the late 40s to the end of the 1950s, the second is from 1960 to 1980 and the third is from 1980 to 2000.

All of these charts tell the same story: until we see a year over year increase in GDP we're not going to see a drop in the unemployment rate. The intuitive reason is pretty simple: businesses need to see a solid reason to hire employees. That solid reason is a growing economy. So, business needs to see a growing economy before they start to hire people. The latest GDP report showed a drop of 1% in GDP. In other words, it's highly unrealistic to expect the unemployment rate to drop given that fact.

Let's look at the current employment situation to gleam some additional information. We'll break it down into initial unemployment claims and then continuing unemployment claims.

Several commentators have noted the 4-week moving average of initial unemployment claims has increased the last two weeks. This is correct. However

notice the overall trend is still down. The 4-week moving average has been dropping since roughly the end of March. In other words, the longer trend for initial unemployment claims is still positive. In addition

despite a recent increase, the Challenger jobs cut report has printed a substantial drop. And finally,

seasonally adjusted mass lay-off events have dropped as have

The total number of mass lay-off claimants.

In other words, additional data points to a continued improvement in the initial unemployment claims data. This means we can expect a slow decrease in the number of people unemployed for different periods of time.

Let's look at the time structure of unemployment. This means we're going to break down the total number of unemployed into the length of time they have been unemployed.

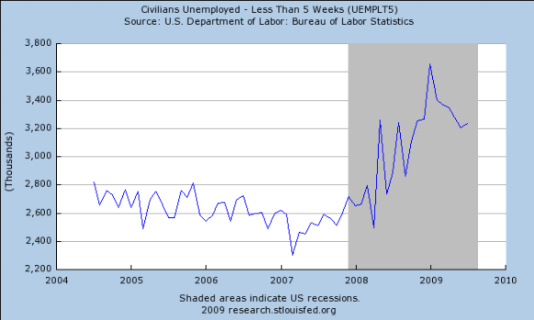

The number of people unemployed for less than 5 weeks has been decreasing since the beginning of the year.

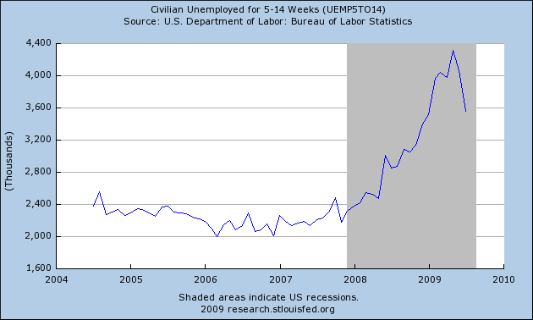

The number of people unemployed for 5-14 weeks dropped in the last unemployment report, as did

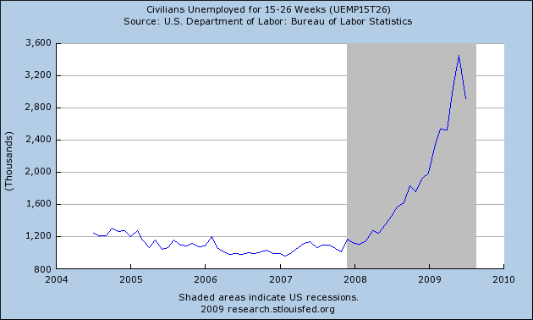

The number of people unemployed for 15-26 weeks. However,

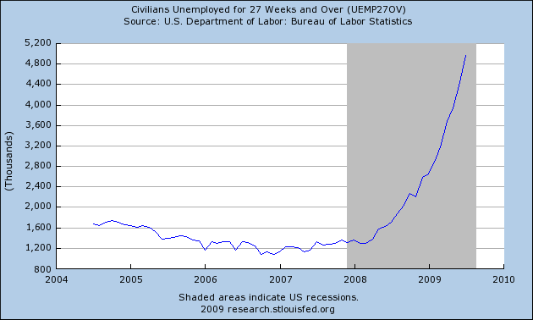

he number of people unemployed for 27 weeks or longer continues to increase and is at an all time high.

-----------------

New Deal democrat here with an assist: the pattern shown by Bonddad above is typical of past recessions and recoveries. Initial jobless claims peak first, then claims 5-14 weeks in length, then 15-27 weeks, and finally claims longer than 27 weeks -- which peak long after the recession is done. Here's the graph showing this progression for the 1970s recessions:

and this one for the 1991 and 2001 recessions:

Returning you now to Bonddad ....

----------------

Let's tie all of this information about unemployment together.

1.) The trend of initial unemployment claims is down. We see this in the 4-week moving average, along with other data such as the Challenger job cut report, the decrease in the number of seasonally adjusted mass lay-off events and the decrease in the number of seasonally adjusted people laid-off in mass lay-offs. Because the number of initial claimants is decreasing, we can expect a slow improvement in the number of people unemployed for various lengths of time.

2.) The structure of unemployment is showing improvement. The number of people unemployed for less than 5 weeks has been decreasing since the beginning of the year. The number of people unemployed for 5-14 weeks and 15-26 weeks dropped in the latest jobs report. The longer term unemployed are still increasing, but given the drops in the other metrics this number should start to show a decrease within the next 4-6 months.

Now -- that leads to the final question: when will the jobs come back? In order for that to happen we need to see at least one quarter of a positive GDP and probably two. That means the soonest we can expect a drop in the unemployment rate would be the a few months from now and that is only under the rosiest of scenarios. The most likely possibility is it won't be until the end of the first quarter of next year before we start to see a ticking down (and that assumes a stronger rate of growth than I think is going to happen).

So, in the meantime what should we do?

1.) Make sure the longer-term unemployed are given benefits and other help to ease their suffering.

2.) Ask ourselves is there a way we can better implement the stimulus money to increase the rate of GDP growth and thereby see a faster drop in GDP?