When the Dutch first travelled up New York’s Hudson River to establish trading posts with the Indians they encountered one of the largest and most powerful Indian confederations in North America: the League of Five Nations, also known as the Iroquois Confederacy. The Iroquois were an agricultural people who lived in permanent villages. They used the symbol of their house—the hodensote or longhouse—as the symbol of their confederacy.

The Iroquois Nations:

While the designation “Iroquois” is often used to refer to the Five or Six Nations, it should be remembered that not all Iroquois-speaking nations in the Northeast were members of the League. The Huron, an Iroquois-speaking confederacy located north of the Great Lakes, was the most prominent Iroquois group which did not belong to the Confederacy.

.

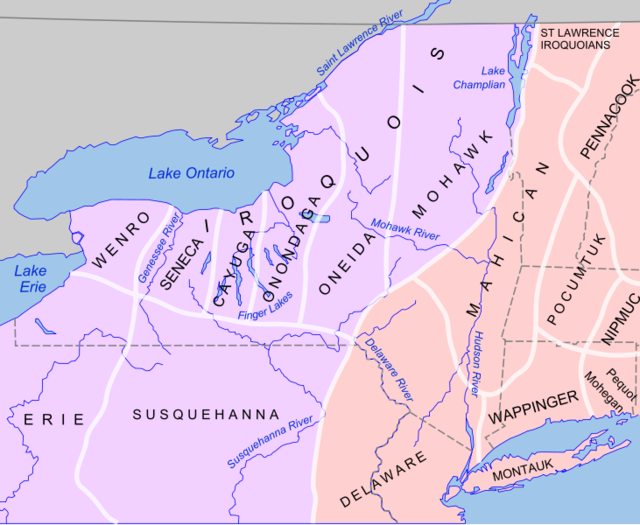

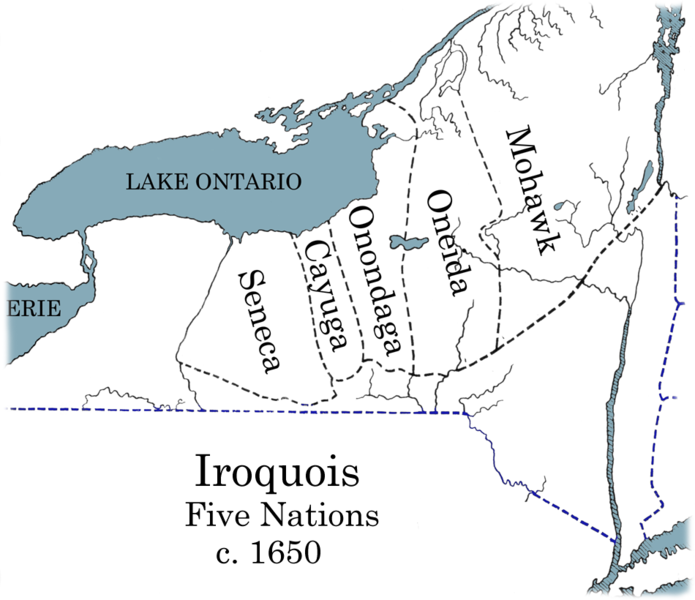

The territory of the original Iroquois Five Nations is called Iroquoia and that of the Huron is called Huronia. The confederated villages of Iroquoia ranged from the Schoharie river in the east to the Genesee River in the west; the Adirondacks and Lake Ontario marked its northern flank, the headwaters of the Delaware, Susquehanna, and Allegheny marked the south. Huronia lay just north of Lake Ontario and was centered at Georgian Bay.

Pictured above is a map showing the location of the Iroquois-speaking nations and their neighbors.

The above map shows the location of each of the five nations about 1650.

The Huron were a confederacy of four major tribes: Bear, Rock, Barking Dogs, and White Thorns (also known as Canoes). The people called their confederacy Wendat or People of the Peninsula. They were given the name Huron by the French.

The French applied the name Neutral to a number of allied Iroquoian-speaking groups who lived between Huronia and Iroquoia. These groups remained neutral in the hostilities between the Huron and the Iroquois. The Neutral groups include Attiragenrega, Niagagarega, Antouaronons, Kakouagoga, and Ahondihronon.

There were also a number of Iroquoian-speaking tribes located along the Saint Lawrence River at the time of first European contact in 1535. However, by 1603 these tribes had disappeared and a number of Algonquian-speaking groups were living in the area. There are many anthropologists and archaeologists who feel that the Saint Lawrence Iroquois were Oneida-Onondaga who had expanded into the area after 1100 and then retreated back to New York after 1535. Others, however, feel that the Oneida, Onondaga, and Saint Lawrence Iroquois were different groups.

The Longhouse:

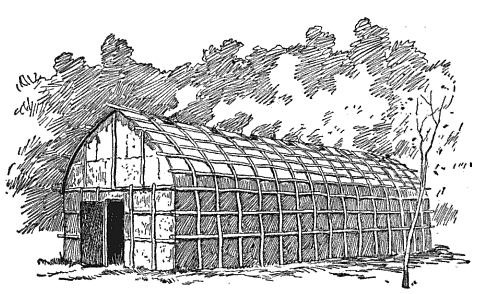

The center of Iroquois life and the symbol of the League of Five Nations was the hodensote or longhouse. This was a large structure – up to 300 feet in length – framed with bent saplings and covered with bark. The average longhouse was 60 feet long, 16 feet wide, and 15 feet high.

Shown above is a reconstruction of an Iroquois longhouse.

The longhouse was occupied by a group of matrilineally related families. Each family had its own compartment within the longhouse. For each two families there would be a hearth, usually spaced at about 20 foot intervals. To let the smoke out, there was a smoke hole—a large rectangular opening in the arched roof—covered by a piece of bark which could be moved by a pole from below.

The two families sharing the hearth would live in compartments across the aisle from each other. Each family’s room was considered its private domestic space and contained sleeping platforms and shelving for storage. Bunks along the inside wall served as beds at night and as benches during the day. A curtain was hung from a pole above the benches. At night, this curtain, which was sometimes painted, would be dropped down providing the bed with some privacy.

Overhead shelves provided storage space for clothing and baggage. Sometimes, children would also be stowed away in this area. Corn, dried fish, and other dried foods were hung on the overhead poles.

Construction of the longhouse began with two rows of forked poles at about four or five foot intervals. The frame for the arching roof was then formed with bent poles attached to the base poles. The structure was strengthened with rafters and additional transverse poles. The structure was then covered with large sheets of bark, usually from cedar, elm, ash, basswood, fir, and spruce. The bark was stripped from the trees in the spring when the sap was flowing.

The longhouse had a door of animal hide or of hinged bark at either end. Over the front door there would be a panel carved or painted with the clan symbols of the families who lived there. Since the clan was matrilineal – traced through the mother – the women owned the houses.

The inside of the longhouse tended to be noisy, crowded, and smoky. The first Jesuits to describe the longhouses reported an abundance of fleas and lice, which they believed were the result of children urinating on the floor.

Villages:

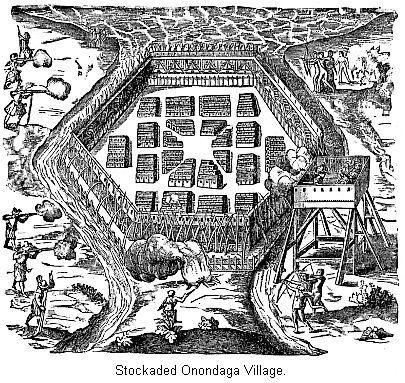

A drawing of an Onondaga village is shown above.

Iroquois villages were usually near streams or rivers. A small Iroquois village might have only four or five longhouses, while a large village would have more than 100. The larger villages were sometimes called “castles” by the European immigrants and had populations of about 3,000 people.

The population of an Iroquois village varied greatly according to the season. During the summer, villages would be nearly abandoned. Men would often leave the village during the summer for extended hunting, fishing, and warring expeditions. Women and children would move to small cabins closer to the fields so that they could tend the crops.

While the Iroquois lived in permanent villages, meaning that these villages were occupied year-round, villages tended to move on a regular basis. After about ten years the farmlands adjacent to the village would begin to become exhausted and crop yields would fall. In addition, it was difficult to keep bark-covered homes up for long periods of time. After about a decade, it was harder to clean and repair the house.

Among the Huron, village size rarely exceeded 1,500 to 2,000 inhabitants. One of the limiting factors was the rapidity with which local resources—firewood being a major concern—were used up. Disputes within a village would sometimes result in a fissioning of the village.

Between the longhouses and around the perimeters of the Iroquois villages were refuse dumps which contained large amounts of organic waste. These conditions would attract blood-feeding insects, like ticks and mosquitoes. It addition, the waste was attractive to scavenging dogs and rodents.

When the villages were moved, not everyone moved at the same time nor to the same location. People were free to move when they wanted and where they wanted. Some people would move to different communities and some to a new location. It would take several years for a village to be completely abandoned.

Iroquois villages were often stockaded and located in easily defensible high places near water. The stockade was made from logs and was often 15 to 20 feet in height. Often the stockades were made in double, triple, and even quadruple lines which were interlaced and reinforced with heavy bark. Some villages had a deep ditch surrounding the village as an additional defense line. On the top of the stockade would be piles of stones which could be thrown down at attackers, and jars of water which could be used to put out fires caused by burning arrows.

A typical village might enclose from five to ten acres within the palisade and would use several hundred acres outside of the palisade for farming.

Cross Posted at Native American Netroots

Cross Posted at Native American Netroots

An ongoing series sponsored by the Native American Netroots team focusing on the current issues faced by American Indian Tribes and current solutions to those issues.