Stanislav Petrov had just settled into the commander's chair for night duty when the Soviet Union's early-warning satellite system reported that all hell was breaking loose.

"Suddenly the screen in front of me turned bright red," said Petrov. "An alarm went off. It was piercing, loud enough to raise a dead man from his grave."

"The computer showed that the Americans had launched a nuclear strike against us."

The uneasy quiet inside a secret bunker at

Serpukhov-15 was disrupted just past midnight on September 26, 1983 by the warning of an incoming attack. The data from the satellite indicated a missile had been launched by the Americans. In a moment, another launch was detected, and then another. Soon, the system was "roaring".

This was not a drill. According to the data scrolling across the screen, the Soviet Union was under attack by five intercontinental ballistic missiles. "The warning system's computer, weighing the signal against static, concluded that a missile had been launched from a base in the United States."

There was precious few seconds to pause. On the panel in front of the 44-year-old lieutenant colonel of the Soviet Air Defense Forces "was a red pulsating button. One word flashed: 'Start.'"

"For 15 seconds, we were in a state of shock," he said. "We needed to understand, what's next?"

Was this the real thing?

"The computer showed that the Americans had launched a nuclear strike against us," Petrov said.

Petrov's job was to monitor and evaluate the incoming satellite data for signs of an attack. His orders were to report the information to his superiors, which in turn would be reported up the command chain quickly rising to the attention of the general secretary. The Soviet counterattack could be underway within minutes.

"I had a funny feeling in my gut," Petrov said.

A solitary missile launch would not normally go up the chain of command, but with a salvo of five incoming missiles, an automated electronic alert already had gone to the general staff headquarters before Petrov could determine if the attack report was actually legitimate.

All around him "electronic maps and consoles were flashing" in the bunker. The stress was intense. Petrov tried to absorb all the information on the screens while another officer was on the phone shouting at him "to remain calm and do his job."

"The thought crossed my mind that maybe someone had really launched a strike against us. That made it even harder to lift the receiver and say it was just a false alarm."

Despite the evidence the early-warning satellite and computer systems were showing him, Petrov decided this must be a computer error and reported it as such. As a software engineer, who had been developing the algorithms for the early-warning systems since the 1970s, Petrov knew the system had been rushed into service "raw" and had its "flaws".

Все программы я учил и знал их гораздо лучше компьютера. Компьютер никогда не может быть умнее человека, создавшего его. Ведь компьютер решает все математически, а у человека в глубине души еще имеется что-то непредсказуемое. И у меня тоже это непредсказуемое чувство тоже было. Поэтому я и позволил себе не поверить системе, потому что я человек, а не компьютер.

|

"I learned and knew these programs far better than the computer. A computer can never be smarter than the person who created it. After all, the computer decides everything mathematically, but there's still something unpredictable in the depths of a person's soul. And I had this unpredictable feeling, too. That's why I allowed myself not to believe the system, because I am a person, not a computer."

|

Petrov was going to disobey procedure and let his intuition overrule the evidence on his screens and report the incident as a glitch rather than as a nuclear attack. "I understood that I was taking a big risk," he said.

"I didn't want to make a mistake. I made a decision, and that was it," Petrov said.

In the end, less than five minutes after the alert began, Petrov decided the launch reports must be false... Petrov's decision was based partly on a guess, he recalled. He had been told many times that a nuclear attack would be massive – an onslaught designed to overwhelm Soviet defenses at a single stroke. But the monitors showed only five missiles. "When people start a war, they don't start it with only five missiles," he remembered thinking at the time. "You can do little damage with just five missiles."

The false alarm was ultimately attributed to the satellite. It had detected the "sun's reflection off the tops of clouds and mistook it for a missile launch." The software was refactored to filter out reports such as this in the future. Instead of getting praised for making the right call, "

Petrov’s base took part of the blame for not developing the system properly."

In 1983, Cold War tensions between the Soviets and Americans had risen to a level not seen since the Cuban Missile Crisis. A declassified article in the CIA's Studies in Intelligence by Benjamin Fischer explained what was happening in 1983:

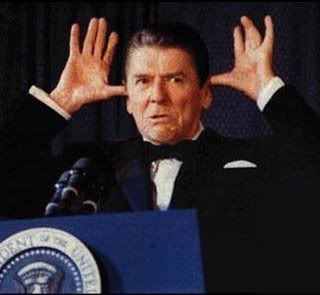

In March, President Reagan referred to the Soviet Union as the "focus of evil in the world," as an "evil empire." General Secretary Andropov suggested Reagan was insane and a liar. Then things got nasty.

Ronald Reagan

The Soviets were suspicious that Reagan's Strategic Defense Initiative, dubbed "Star Wars", was a plan by Americans for a first strike nuclear attack capacity. The United States was set to begin deployment of Pershing II missiles to West Germany by the end of the year.

"For the first time since 1953, a Soviet leader was telling the Soviet people that the world was on the verge of a nuclear holocaust." People on both side of the east-west divide were concerned that conflict would start because of a miscalculation.

Soviet General Secretary Yuri Andropov warned US envoy Averell Harriman that the Reagan administration's provocations were moving the two superpowers toward "the dangerous 'red line'" of nuclear war through "miscalculation" in June of 1983.

The Reagan administration was conducting a "covert political-psychological effort to attack Soviet vulnerabilities and undermine the system," Fischer wrote.

The PSYOP was calculated to play on what the White House perceived as a Soviet image of the President as a "cowboy" and reckless practitioner of nuclear politics. US purpose was not to signal intentions so much as keep the Soviets guessing what might happen next...

The US sent bombers over the North Pole toward Russia or flew squadrons "straight at Soviet airspace" so their "radars would light up and units would go on alert. Then, at the last minute, the squadron would peel off and return home."

Meanwhile, NATO was busy preparing for Able Archer 83, a ten day military exercise in Western Europe in November that would simulate a DEFCON 1 nuclear alert.

According to declassified back channel discussions, Soviet sources warned that there was "growing paranoia among Soviet officials" and they were "literally obsessed by fear of war."

This fear was leading to deadly mistakes. Just three weeks before the incoming attack alarms were sounding inside the secret bunker south of Moscow where Col. Petrov sat, a Soviet Su-15 interceptor shot down Korean Air Lines Flight 007 killing all 269 passengers and crew aboard, including a sitting member of the U.S. Congress, Rep. Larry McDonald of Georgia.

The situation on that September night was real and it was dangerous. The world could have ended thirty years ago. Thankfully, Petrov trusted his gut rather than what the computers were telling him. Earlier this year, he was awarded the Dresden Preis.

"At first when people started telling me that these TV reports had started calling me a hero, I was surprised. I never thought of myself as one – after all, I was literally just doing my job."