For three days in June, 1943, blacks and whites in Detroit fought a battle that killed 34 people, wounded 433, and destroyed more than $2 million in property. The United States has a long history of racial discrimination which periodically erupts in violence such as the Detroit Race Riot.

In 1943, the United States was engaged in World War II and Detroit’s auto industry had been converted to manufacturing goods for the war effort. The city became known as the “arsenal of democracy.” With the war, Detroit’s population was booming with large numbers of people being attracted to the city because of high wages and available jobs. However, housing had not kept up with demand. While the war industry provided lots of jobs, it did not provide housing for the thousands of workers who were migrating to the city.

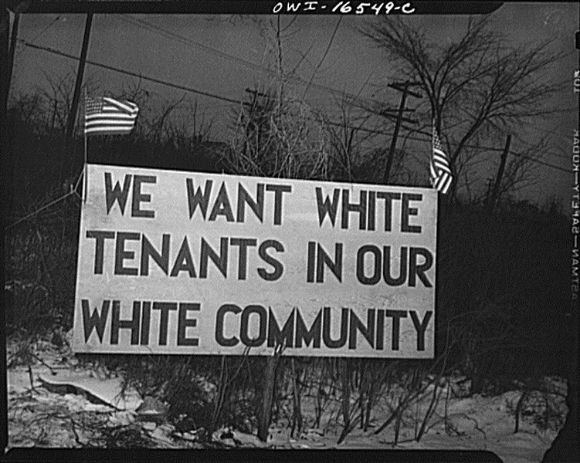

Many of the newcomers who were flooding into the city were rural whites from Appalachia and the South. They brought with them cultural notions of white racial superiority and Jim Crow.

Recruiters for the war industry plants convinced both blacks and whites that there would be higher wages in the new war factories. To many Southern blacks, Detroit sounded like the promised land. In Detroit, however, they found a continuation of the racism that had suppressed them in the South.

Housing in booming Detroit was scarce and the blacks soon found that they had to pay rents which were two to three times higher than those paid by whites. In addition, they were often forced to live in homes without indoor plumbing. They were excluded from all public housing except for the Brewster Housing Projects.

As with other American cities at this time, housing in Detroit was racially segregated. However, the federal government had selected a site for the public housing for black defense workers which was in a white neighborhood. The new black housing unit was named Sojourner Truth in honor of a black woman. Whites in the area strongly opposed the idea of allowing blacks to move into an all-white neighborhood. As a result of the white complaints, the government announced that Sojourner Truth would house whites and another location would be selected for blacks.

When no suitable site for a black housing unit could be found, the government announced that blacks would be allowed into the finished homes beginning on February 28, 1942. On February 27, there was a cross burning near the homes. In spite of opposition from whites, black families were moving into the project by the end of April.

To protect the blacks in the housing development, city and state police as well as 1,600 Michigan National Guard troops were mobilized to protect the 168 black families in the Sojourner Truth homes.

Black workers were generally given the lowest-paying, dirtiest, and most unsafe jobs. Work environments were segregated and blacks were usually not considered for promotion. In June 1943, the Packard Motor Car Company promoted three blacks to work on the assembly lines next to whites. In response, 25,000 white workers walked off the job. The plant produced engines for bombers and PT boats and the walkout slowed down critical war production.

On Saturday evening, June 20, 1932 a fist fight broke out between a white sailor and a black in an integrated amusement park known as Belle Isle. It quickly escalated into a confrontation between groups of blacks and whites. There was a rumor among the blacks that a white mob had thrown a black mother and her baby into the Detroit River. Among the whites there were rumors that blacks had raped and murdered a white woman.

In Paradise Valley, one of the oldest and poorest Detroit neighborhoods, stores in the black neighborhood were looted and buildings burned. The Paradise Valley neighborhood was home to 200,000 blacks living in an area of 60 square blocks.

After three days of rioting, more than 6,000 federal troops restored the peace. Of the 34 people killed, 25 were blacks--and of these, 17 were killed by police. Three-fourths of those injured were blacks and 85% of those arrested for rioting were blacks.

Following the riot, white city leaders blamed the incident on young black “hoodlums.” The fact-finding committee appointed by the city’s mayor quickly laid the blame on the city’s black population. The county prosecutor claimed that the riots were instigated by the leaders of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). The NAACP had held an emergency war conference in Detroit which had called attention to the hypocrisy of talking about personal freedoms abroad while maintaining discrimination and segregation in the U.S.

Black leaders, on the other hand, pointed to job discrimination, housing discrimination, police brutality, and racism as the causes of the violence. The NAACP’s Thurgood Marshall (who would later become a Supreme Court Justice) pointed out that the police had deliberately targeted blacks while ignoring white atrocities. According to Marshall:

“This weak-kneed policy of the police commissioner coupled with the anti-Negro attitude of many members of the force helped to make a riot inevitable.”

Outside of Detroit, the chairman of the House Un-American Activities Committee blamed the riots on Japanese-Americans who had infiltrated Detroit’s black community to spread white hatred and disrupt the war effort. In Mississippi, Eleanor Roosevelt was blamed for the riots. President Roosevelt, fearing protests from the southern wing of the Democratic Party, did not make any public statements on the riot or on the issue of racial problems.

On the international front, both the Japanese and German news media promoted the idea that the United States was a country torn apart by social injustice, race hatred, and gangs.