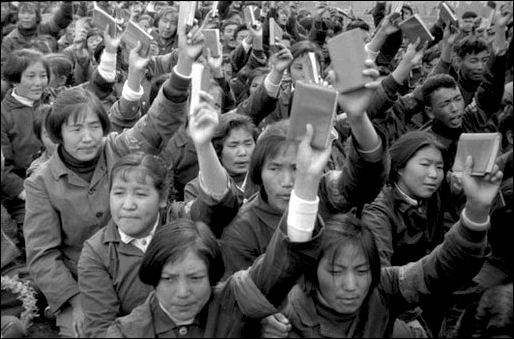

Mass rally in Tiananmen Square during the Cultural Revolution with crowd waving Chairman Mao's "Little Red Book"

You can't understand today’s China unless you try to understanding the ten catastrophic years of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, a social and political movement that Mao Zedong, Chairman of the People's Republic of China, launched in 1966 and that lasted until Mao’s death in 1976. Many Chinese people's cynicism about politics, the Communist Party's extremely cautious and anti-democratic approach to governance, the rise of “princelings” (the sons and daughters of the original generation of revolutionaries) to positions of political power and staggering wealth, the violent suppression of the Tiananmen Square student protests, Falun Gong and other non-conformist movements, the complicated transition in power taking place these days in Beijing, all have their roots, in part, in the Cultural Revolution. The problem is that the Cultural Revolution is itself almost impossible to understand.

The Cultural Revolution has been difficult to understand for two main reasons. First, accurate information about the events of the Cultural Revolution was almost impossible to obtain inside or outside China while it was happening and for many years after, and is still fragmentary. China was one of the most closed societies on earth at the time to foreigners - almost more closed then, than North Korea is today. There was no technology to work around official statements, propaganda and news outlets. The government under Mao also suppressed information and analysis within China that did not conform to their ever increasingly fantastical and unrealistic views of reality. Fortunately, after Mao’s death and after the beginning of the reform era, the government allowed cautious exploration of the history of the Cultural Revolution, but documentary information is scattered, much is still secret, the government actively suppresses some historical investigation of sensitive topics, and the memories of victims and perpetrators are fading. According to political science professor Zhang Ming of Renmin University in China, a thorough, accurate and public accounting of the Cultural Revolution in China has not occurred and many people who didn’t live through it don’t know how terrible it was, and more frighteningly, many have become nostalgic for that era. Fortunately, by the late 1980s, a genre of Chinese memoir and fiction about the psychic wounds left by the Cultural Revolution – often called “scar literature” – had emerged in China and in the overseas Chinese diaspora, and scholars have begun amassing histories, documentaries and data bases, although there is some resistance to accepting the dire portrayal of China in that era.

This, however, has created the second reason the Cultural Revolution is difficult to understand – namely, that the more we know about it, the crazier it seems. People in the West didn't fully understand what was going on and as information and histories emerge here, it becomes more puzzling. We didn't know how violent and anarchic it was, nor how close the Chinese government came to completely collapsing. Even with the flowering of research and source gathering of recent years, it's difficult to understand why Mao launched such a destructive campaign against his own state and party. Also, the mass mobilization manipulated but not controlled by the government, the ideological struggles, “ultra left” politics and mind numbing violence, chaos, anarchy and disorder are very difficult to understand considering this was taking place in an otherwise tightly controlled totalitarian nation state. The Cultural Revolution was one of the most perplexing movements of the twentieth century, a convulsion of ideological fanaticism and political violence carried out by millions of young people devoted to Chairman Mao and his political theories, called "Mao Zedong Thought," who were generally organized as “Red Guards.” I’ve been immersed in reading about the Cultural Revolution for many months for personal reasons – I met a former Red Guard last summer and have had some interesting conversations with her daughter, who is a writer, researcher, translator and friend. One thing I’ve learned is that many younger Chinese people whose elders lived through the period believe that the period affected them pervasively, permanently and negatively. I don’t pretend to be an expert on China's Cultural Revolution at all, but I would like to share what I’ve learned the last few months in this series of DailyKos diaries.

If you live in the West but have some knowledge of China, your image of the Cultural Revolution is probably like mine was – it was an era when Mao held mass rallies of high school and college students,  all of them grasping the “little red book” of Chairman Mao’s quotations, chanting slogans and, when not at rallies, ransacking temples, libraries, museums and other cultural institutions, to destroy the “four olds” – "old customs, old culture, old habits and old ideas - while also berating hapless “intellectuals,” bureaucrats, “capitalist-roaders” and other people deemed “counter revolutionary.” There were even people in the West who saw the Cultural Revolution as a positive development, an example of extreme democratization and egalitarianism, and it’s pretty clear that few westerners really knew what was happening other than what was promoted in Chinese propaganda. (Surprisingly, the U.S. CIA at times had a remarkably good idea of what was happening in real time, as did China’s arch enemy, the government of Taiwan, the Republic of China, but their correct information was thoroughly mixed with misinformation making analysis difficult.)

all of them grasping the “little red book” of Chairman Mao’s quotations, chanting slogans and, when not at rallies, ransacking temples, libraries, museums and other cultural institutions, to destroy the “four olds” – "old customs, old culture, old habits and old ideas - while also berating hapless “intellectuals,” bureaucrats, “capitalist-roaders” and other people deemed “counter revolutionary.” There were even people in the West who saw the Cultural Revolution as a positive development, an example of extreme democratization and egalitarianism, and it’s pretty clear that few westerners really knew what was happening other than what was promoted in Chinese propaganda. (Surprisingly, the U.S. CIA at times had a remarkably good idea of what was happening in real time, as did China’s arch enemy, the government of Taiwan, the Republic of China, but their correct information was thoroughly mixed with misinformation making analysis difficult.)

In fact, the Cultural Revolution was much, much worse and more far reaching than people in the west generally understood at the time or than most younger people in China or overseas understand today. It was so awful, that many people reject the new information about it that is coming out as either implausible or too embarrassing to acknowledge.

What Was the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution?

If I had to describe the Cultural Revolution as succinctly as possible, I would say it was Chairman Mao’s astonishing, nation wide attack on, and eventual demolition of, first the educational system, then intellectuals, Chinese culture, the very idea of expertise, and finally his own government and party.

When the Cultural Revolution was over in 1976, China was in a complete shambles. Its economy was barely functioning and its production units were bloated with political appointees. Its educational system had almost been destroyed and one of its leading universities closed. It had a lost generation of young people who either had not been educated, had been badly educated, or had been well educated but then "sent down to the country" to "learn from the peasants" in many cases for a decade. China's technological and scientific advances had been reversed, its bureaucracy smashed and cadres (government and party workers) harassed, denounced, beaten and in many cases killed, scaring off young talented people from working for the government. China's politics had been poisoned by Mao's reversals, purges and political killings even of the highest officials. Before Nixon’s famous trip in 1973, China had been diplomatically isolated even in the communist world and third world. One of the interesting criticisms of “scar literature” memoirs is that many people simply think that the horrors these books describe could not have happened, or are hyped for a western audience that wants to think the worst of China, or that certain kinds of people couldn’t have been Red Guards or couldn’t have been the victims of Red Guards. One thing I’ve learned in the last few months is that almost nothing is too far fetched to believe about what happened, and much of the worst is now very well documented by scholarly literature, and tens of thousands of primary documents and footnotes.

The mystery is why did the Chinese people, especially Chinese students, young people and children (and many were children) seem to go collectively insane? Why would the supreme leader of China declare war on his own government and party? Why was it a “Cultural” Revolution rather than a political revolution?

Actually most of these questions have logical answers, but the answers require a lot of background. It’s also easier to understand the Cultural Revolution by focusing on individuals -- their stories, their predicaments, their choices and the logic of their seemingly illogical behavior -- rather than on the more academic historical approach of focusing on groups, classes and interests. So these diaries will focus on a small cast of people who I hope will become real for you – President Liu Shaoqi, his wife, the first lady of China, Madame Wang Guangmei, and their daughter Liu Tingting; a school boy Red Guard from the coastal city of Xiamen who wrote one of the first scar literature memoirs under the pseudonym, Ken Ling, and his buddies, including a Red Guard girl leader nicknamed Piggy and Ling’s girlfriend, nicknamed Meimei; an economics instructor at Beijing University, Nie Juanxi; Kuai Dafu, a leader of the Red Guard at Tsingua University; Jan Wong, a teenage Canadian-Chinese radical Maoist who became one of revolutionary China’s very few North American foreign exchange students; Song Binbin, a Red Guard at the high school attached to Beijing Teacher’s University; and of course Chairman Mao and his wife, Jiang Qing. Another reason to focus on these people is that thanks to recent research and the reach of the internet, it’s possible to sketch out the remarkable fates of those who survived – a sort of “where are they now” that is almost as unbelievable as their experiences during the Revolution.

But before the background, here is a sketch of the violent first months of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution.

The First Victims: The Attack on Teachers

The first seemingly inexplicable events of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution were violent attacks on teachers in the summer of 1966. The Cultural Revolution’s start is usually dated some months earlier in May (more about that in a subsequent installment), but the “Red August” of 1966 is usually considered the start of violence, and

the early violence was directed mostly at teachers. Chinese culture historically placed an extremely high value on education and Chinese people generally revered teachers. Attacks against teachers were almost unthinkable. In some memoirs, students who recalled attacking their teachers could, many years later, barely understand why they had done what they did.

Researchers believe the first attacks on teachers began at elite high schools in the capital, Beijing, especially in high schools connected to Beijing’s major universities. (In English translation, these schools are typically called “middle schools,” but given the ages of the students, they would be called “high schools” in the U.S.) The Beijing students who started the Red Guard movement held some of the most coveted school seats in the entire country, considering how poor China still was and how under-developed its educational system outside the major cities was, and how difficult it was just to be permitted residency in Beijing. Many of the Red Guards who attacked teachers were the children of very senior members of the Communist Party, military and government who were given favoritism in admissions to the nation's best schools. Similar events unfolded at Beijing’s elite universities and colleges, and even in elementary schools. In the early summer of 1966, the central government issued orders that all schools nationwide were to cease teaching ordinary curriculum and focus exclusively on revolutionary education and “Mao Zedong Thought.”

One of the first brutal attacks on a teacher in Beijing appears to be the attack on Liu Meide, vice principal and chemistry teacher, at Beijing University’s attached middle school on July 31, 1966. Answering Mao’s call to make revolution, the students beat principal Liu, cut off her hair, stuffed dirt in her mouth and made her kneel on a table, where one student put his foot on her back, in a pose that Mao had once recommended for use against counter-revolutionary landlords – all despite the fact that she was pregnant. They then kicked the table from under her causing her to fall in such a way that killed her unborn child.

One of the first teacher killings took place a few days later at Girls Middle School attached to Beijing Teachers University on August 5, 1966. Tenth graders had identified five counter-revolutionary teachers and administrators, whom they labeled the “black gang.” The school girls forced the teachers to wear dunce caps, splashed ink on them, forced them to wear boards hung by ropes around their necks spelling out their names and crimes, poured boiling water on them, and beat the teachers with boards spiked with nails. The vice principal and highest ranking teacher, teacher Bian Zhongyun, died after three hours of torture and her body was dumped in a garbage cart.

Adding to the tragedy of her death is the fact that it came after a longer period of abuse and torture that she had informed the authorities about. She had written a letter on June 29 complaining about abuse she received at the hands of her revolutionary students during an event on June 21:

“I was forced to wear a high hat, lower my head (eventually, bending over at a ninety-degree angle), and kneel on the ground. I was beaten and kicked. My hands were tied behind my back. They hit me with a wooden rifle that was used for militia training. My mouth was filled with dirt. They spat in my face.”

The authorities never responded to her complaints and just over a month later her students had killed her.

At the middle school attached to Tsinghua University, students beat teachers with clubs, whips and belts, causing one teacher internal organ damage, another teacher to lose sight in one eye and one teacher to commit suicide.

Professor Wang Youqin of the University of Chicago has, through many years of research, tried to compile a comprehensive sample survey of violence against teachers in the early phase of the Cultural Revolution, especially in Beijing, where the violence began before spreading across the entire country, based on extensive interviews and reviews of available documents. In the 96 schools she surveyed, 27 teachers were killed. In addition, several students identified as counter revolutionaries were killed. In all 96 schools Professor Wang has studied, teachers who weren’t killed were physically attacked, beaten, tortured, imprisoned and humiliated. If her sample is representative, that would mean that in about 1/4 to 1/3 of middle schools, at least one teacher was killed in the summer of 1966 alone, that in several schools there were multiple teacher killings, and that in almost every school teachers were physically attacked, tortured, kidnapped and imprisoned by their students. Students in Beijing and across the country turned classrooms into makeshift prisons, called “black dens,” where they kept the condemned teachers, torturing them daily. Many teachers who weren’t killed suffered permanent physical and mental injuries, and many committed suicide. Needless to say, many teachers came to hate teaching, education and students.

Some of the earliest Red Guard were from elite Communist Party families. For example, one school girl at the Girls Middle School where vice principal Bian was killed, was Liu Tingting. She was a leader of the Red Guard in her school and the daughter of the President of China, Liu Shaoqi. She is reported to have told a friend in 1967, somewhat ambiguously, “It was glorious to beat people to death at that time. So I exaggerated and said that I had beaten three people to death.” (There was a terrible tragic irony in Liu’s statement considering what happened later to her family at the hands of Red Guards, about which there is much more in a subsequent installment.)

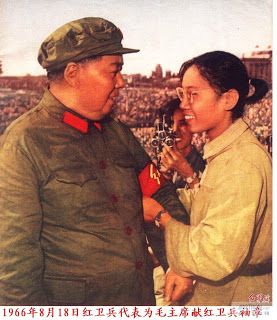

Another Beijing school girl, Song Binbin, daughter of General Song Renqiong, became a Red Guard icon because of one of the most famous pictures ever disseminated by China’s propaganda channels during the Cultural Revolution.

At a mass rally in Beijing on August 18, Song Binbin presented Chairman Mao with a red armband – the insignia of the Red Guard – and Mao smilingly accepted it. In the highly symbolic political theater of the Cultural Revolution, this was taken to mean that Mao approved of the formation of the Red Guard and their violent actions. Because there had been many different kinds of revolutionary student organizations before that rally and because many organizations restyled themselves as Red Guards after Mao's approval, Song is sometimes credited with having “started” the Red Guards as the main approved type of organization, but also setting it on the path of violence. Song Binbin, herself, had been a Red Guard leader at the middle school where vice principal Bian was killed and Song had herself reported the killing to the authorities. At the rally, Chairman Mao had asked Song’s name and when she told him it was “Bingbing,” meaning “refined" or "courteous,” Mao told her, “Want violence!” The press began reporting that she had accepted the new name Mao had given her, and for propaganda purposes, she became known as “Song Yaowu” or "Song wants violence."

At a mass rally in Beijing on August 18, Song Binbin presented Chairman Mao with a red armband – the insignia of the Red Guard – and Mao smilingly accepted it. In the highly symbolic political theater of the Cultural Revolution, this was taken to mean that Mao approved of the formation of the Red Guard and their violent actions. Because there had been many different kinds of revolutionary student organizations before that rally and because many organizations restyled themselves as Red Guards after Mao's approval, Song is sometimes credited with having “started” the Red Guards as the main approved type of organization, but also setting it on the path of violence. Song Binbin, herself, had been a Red Guard leader at the middle school where vice principal Bian was killed and Song had herself reported the killing to the authorities. At the rally, Chairman Mao had asked Song’s name and when she told him it was “Bingbing,” meaning “refined" or "courteous,” Mao told her, “Want violence!” The press began reporting that she had accepted the new name Mao had given her, and for propaganda purposes, she became known as “Song Yaowu” or "Song wants violence."

Chairman Mao, General Lin Biao and Red Guards, including Song Binbin

The Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution arrived in the coastal town of Xiamen (known in the West then as Amoy) also in early June of 1966 with a broadcast from Beijing calling for normal education to cease and for students to focus on revolutionary ideology and weeding out counter revolutionaries among the faculty. At Xiamen Eighth Middle School, where Ken Ling was a top student, after a several days of study, gathering of accusations, and writing and drawing of big posters denouncing faculty members, the violent revolution was launched with an attack on teachers and administrators who were forced to parade around the school grounds in dunce caps and with signs hanging from their necks. A vice principal was denounced for being a gay or bisexual man, while the principal was accused of having affairs with several of the young female teachers. The revolutionary students locked the principal and several other denounced teachers into a classroom that was converted into a makeshift prison, where they were forced to live full time, apart from their families, and were continuously “interrogated” and abused.

At Xiamen Eighth Middle School, students killed several teachers that summer. One was a once beloved older teacher of Chinese language, Chen Ku-teh who students accused of having been a rightist and having said critical things about the communist government in class. Unlike other teachers, he refused to “confess” his crimes; this enraged the students and caused them to escalate the beatings. The students dragged him up several flights of stairs lined with students armed with sticks who beat him, then dragged down the stairs. After some time undergoing this torture, teacher Chen lost control of his bowels and a student shoved a stick into his rectum, after which he lost consciousness and later died. At the same school, physics teacher Huang Zubin was beaten to death. On the first day of torture, students hung pails filled with heavy rocks around the necks of teachers causing the string to cut into their flesh. Students at Xiamen Eighth Middle School took “shifts” of beating certain imprisoned teachers day and night, and during a lull in the nightly torture when the students grew tired and went to sleep, teacher Sa Zhaochen jumped from the fourth floor, killing himself. Another teacher attempted suicide by hanging himself, but failed, and was denounced for the attempt at a public humiliation session.

Because Chairman Mao wanted to spread youthful “revolution-making,” the government issued strict decrees that the police were forbidden from interfering with the violent actions of the young Red Guard. This emboldened them to become ever more violent. Ken Ling recalled that policemen gripped their holstered guns when Red Guard were around because Red Guard youth would otherwise brazenly seize their guns. In another anecdote, Ling describes his Red Guard unit attacking a police station, beating the policemen and seizing their weapons. Hence, one factor in understanding the ultra violence of the Cultural Revolution was that very young, very impressionable people had been persuaded by the highest authorities in the country to behave in violent lawless ways, and security forces were strictly forbidden from interfering with their anarchy.

The Cultural Revolution on University Campuses

During the violent summer of 1966, the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution was primarily concentrated in schools and universities. It had begun, however, a few months earlier in the realm of theater. In a complicated political intrigue, a play was staged in Beijing about a dynastic emperor and a faithful official, that some people interpreted as a criticism of Mao (the emperor); under the guidance of Mao and his wife, Jiang Qing, a former actress deeply involved in cultural matters, newspapers and propaganda outlets unleashed vitriolic criticism of the play and by extension, of the Mayor of Beijing who had allowed the play to be staged, and by extension from the Mayor to the President and head of state, Liu Shaoqi.

Few people in China outside of the highest political circles and few people outside China knew that Mao had been effectively deposed from power in 1961 because of his disastrous economic policies (the Great Leap Forward) that had led to massive famine and the deaths of tens of millions of Chinese people.

Between 1961 and 1966, China was essentially being governed by three men representing the three main offices – President Liu Shaoqi , the head of state; Premier (i.e., Prime Minister) Zhou Enlai, the head of the government; and Deng Xiaoping, secretary general or head of the Communist Party – who together had brought the Chinese economy back from disaster by undoing some of Mao’s more radical collectivist vision for rural economic organization. All were able administrators who believed in the orderly development of China’s government and economy, and President Liu, in particular, was influenced by the model of the Soviet Union, where he had studied; he believed that China’s educational sector had to focus on training students in science and technology, social sciences and other technical skills that the country would need to build communism. Yet Mao remained the figurehead and in public all Chinese leaders paid slavish devotion to “Mao Zedong Thought.” According to many sources, Mao was also brooding about the loss or revolutionary fervor that was being replaced by a growing bureaucracy, and angry that the three men running China were no longer even consulting him on major issues. Moreover, Mao now hated the Soviet Union, its leader, Nikita Khruschev, and its economic system, which was often called “Soviet revisionism” or just “revisionism” or more pejoratively the “capitalist road,” and its adherents “capitalist roaders.” He believed that the purpose of schooling was to create revolutionaries, not technicians, and that only when communism had been fully implemented as a political system could schools turn their attention to technical matters. (A subsequent diary will go into much more detail about the conflict among these elites.)

The Cultural Revolution on university campuses was initially somewhat less violent than on high school campuses, although this would not last. The centers for university Red Guard actions were two of China’s most elite universities in Beijing – Beijing University and Tsinghua University. While both are elite, Tsinghua is somewhat more technically oriented. (You can think of them as being somewhat analogous to Harvard and M.I.T.) The basic conflict on university campuses was a reflection of the conflict between Chairman Mao and President Liu: Was the purpose of the university to train technically competent people using standards of academic excellence? Or was the purpose of the university to help carry out permanent revolution, primarily training students in revolutionary theory, while weeding out capitalist roaders and bourgeois holdovers from before the founding of the communist state? Should people be admitted to universities because they did the best on examinations, criteria that would tend to favor the children of the wealthy, of the bourgeoisie of the old regime, and of intellectuals? Or should the children of the favored “five red classes” –- workers, peasants, soldiers, communist party cadres and revolutionary martyrs -- receive preference under a kind of affirmative action program? In understanding this and other conflicts in China at the time, it’s important to keep in mind that although China was ruled by the Communist Party, the vast majority of Chinese people were not members of the Communist Party, which was a very selective “vanguard” party, and that just 18 years after the communist takeover, many institutions, including universities, were still being run the way they had been run under the Nationalist government. There were still private businesses and tradesmen especially in China’s southeast coastal economic heartland and the issue of communist transformation was a very hot topic. Universities and educational bureaucracies across China continued to maintain high academic standards through an system of examinations –- a system that ran counter to Mao’s philosophy.

Some commentators credit a young Beijing University faculty member, Nie Jianzi, for “starting” the Cultural Revolution on campuses. Sometimes she is referred to as a professor of philosophy, but a few more scholarly accounts describe her as being a faculty member of the Economics Department, as well as the secretary of the Communist Party cell of the Philosophy Department. Professor Nie was older than most Red Guard. She was in her 40s, and was a military veteran of the wars against Japan and the Nationalists, and therefore, in the thinking of the time, she had an excellent political and class background, although it’s not clear that she had much academic training.

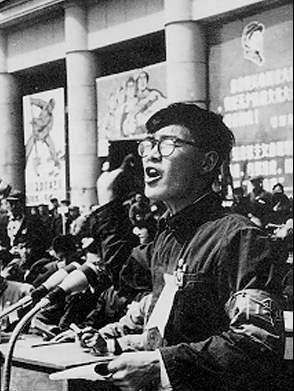

Throughout the 20th century in China, when the public has been mobilized to participate in political discussion, one of the ways this happens is through the writing of petitions and arguments in the form of posters – usually translated into English as “big character posters.”

On May 25, 1966, Nie Jianxi wrote a big character poster attacking several high ranking officials of the university and educational bureaucracy entitled, “Just What Are Song Shuo, Lu Ping and Peng Peyiun up to in the Cultural Revolution?” A week later, China’s radio broadcasting station praised Nie’s poster and a few days later these high ranking officials were dismissed.

Two months later, Mao Zedong himself praised Nie’s poster as “the first Chinese Marxist-Leninist big character poster.” Recent scholarship strongly suggests that high ranking officials in the Communist Party close to Mao were involved in promoting her actions and Nie became a close protege of Mao’s wife, Jiang Qing, during the chaos that engulfed Beijing University and the other schools and universities of the capital. As the Cultural Revolution progressed and fragmented, students engaged in frantic production of big character posters, as well as tearing down competing groups posters. Student fights over big character posters, the various interpretations of revolutionary ideology, and mutual accusations of counter revolutionary activity eventually escalated into fist fights, and then all out paramilitary battles.

Nearby, at Tsinghua University a student rather than a faculty member took the lead in launching the Cultural Revolution on campus.

Kuai Dafu was a popular student of peasant and soldier “class background,” powerfully built, courageous and also a D.J. of the college radio station. Kuai became known as an ultra leftist once the Cultural Revolution began, and eventually developed the charisma and aura that in the west would be associated in the 1960s with a “rock star.” In his fiery speeches, Kuai attacked the bourgeois reverence for expertise in academics and asserted that the purpose of the university was to prepare students to continue carrying out the incomplete communist revolution. Kuai would rise from being an engineering undergraduate to playing a major role in overthrowing the President of China, Liu Shiaoqi and the first lady, but when the Red Guard fell into faction fighting, Kuai became an ultra violent “commander” of a Red Guard battle group, armed with spears, rocks, bricks, Molotov cocktails, guns and an improvised tank, a tractor fitted with armor plating. During early "struggles" against the party bureaucracy at the university, several women party secretaries were publicly stripped naked and sexually assaulted by young men of rival factions. When the government tried to gain control of the campus by sending in troops of the People’s Liberation Army and a contingent of workers, Kuai and his battle group tried to fight them off with the results that the Tsinghua campus was littered the bodies of scores of dead and wounded students, soldiers and workers.

By the end of the summer, the Red Guard had begun spreading outside Beijing, and in Beijing, outside of the schools. According to Professor Wang, in Beijing, Red Guard began beating, harassing, torturing and killing hundreds of people outside of their schools on the streets and in homes. Basing her conclusions on official documents, Professor Wang found that in just one week, from late August to early September, Red Guards in Beijing killed 100 to 200 people daily, and lacking guns at this point, the killings were carried out by torture and beatings. For example, official tallies showed that on August 26, they killed 126 people; on August 27, they killed 228 people; on August 28, they killed 184 people; and the tally continued on and on. For August and September, she concludes the Red Guard killed 1,772 people in Beijing alone.

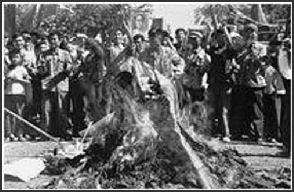

Students carried out some of the violence outside of the schools and universities as an answer to Mao's call to smash and "four olds" -- old customs, old culture, old habits, and old ideas. As I'll try to explain in a subsequent diary, Chinese activists across the political spectrum -- liberals, nationalists, and communists -- had long had complicated feelings toward traditional Chinese culture, and many believed that when China was forced to open to the west in the mid to late 1800s, old culture prevented China from adapting to western technology and statecraft as Japan had done. What to get rid of and what to keep was complicated and controversial. Intellectuals developed a strong consensus that some cultural practices had held China back (like foot binding of women, arranged marriage, governance by Confucian rites instead of science) but others were more difficult to assess, like Confucian ideas about statecraft and family life. In the Red Summer of 1966, Mao and his allies encouraged young people to indiscriminately attack old culture, and in response, Red Guards ransacked libraries, burned books, destroyed temples, defaced adornments of buildings, and wrecked cemeteries.

By the fall, Red Guards began invading neighborhoods, especially better off areas, barging into homes, searching for hidden money, and destroying families' art, books, ceramics, shrines and other objects. People were forced to "confess" that they harbored objects of feudal culture. If people refused or resisted, Red Guards violently "struggled" them.

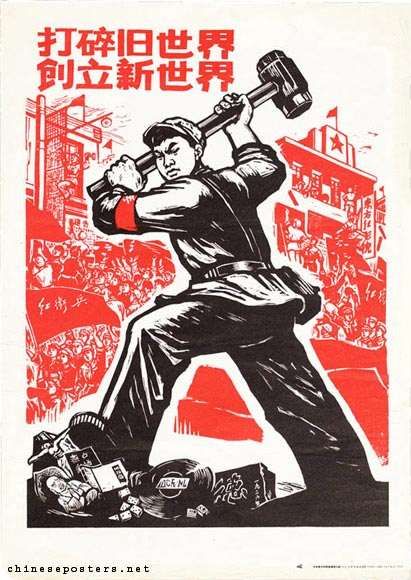

The propaganda posters produced by the government and Communist Party in the 1950s and early 1960s tended to show model peasants, workers and soldiers happily working or realistic depictions of Mao walking with people from various walks of life. Once the Cultural Revolution began, propaganda posters became increasingly abstract and violent, depicting young people destroying things.

The students at the elite Beijing area Tsinghua University Middle School published a manifesto explaining their destructive methods:

Revolutionaries are Monkey Kings, their golden rods are powerful, their supernatural powers far-reaching and their magic omnipotent, for they possess Mao Tsetung’s great invincible thought. We wield our golden rods, display our supernatural powers and use our magic to turn the old world upside down, smash it to pieces, pulverize it, create chaos and make a tremendous mess, the bigger mess the better!

Red Guard manifesto

Tsinghua University Middle School

Peking, June 24, 1966

This was just the beginning of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution’s violence, but not the beginning of its ultra violence. Ironically, the most ultra violent episodes of the Cultural would come in 1967 and 1968 as the movement fragmented and various Red Guard factions began fighting each other –- all while claiming the mantle of being “true” revolutionaries and followers of Mao Zedong Thought. At the height of the violence, Red Guard and other violent militias and factions raided Army bases and seized very heavy military weapons – machine guns, tanks, armored personnel carriers, bombs and grenades – to turn on each other. By 1968, China was experiencing regional civil wars. Factions began killing each other in the thousands, and according to contemporary news reports, the Army, unable to keep up with disposing such large numbers of bodies claimed by the “revolution-making” began dumping corpses in rivers and the ocean – for example, on July 4, 1968, 7,000 corpses had to be pulled out of the waters at Wuchow in Kwangsi, and 8,000 corpses were dumped and floating in the West River in Guangdong. Bodies began washing up in the British colony Hong Kong – which itself was almost engulfed by the Cultural Revolution, which Maoists there sought to use to topple British rule. And even that ultra violence could not compare to the unthinkably gruesome violence that engulfed Guangxi Province as the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution spread to very remote peasant areas where people had almost no understanding of the vast political drama they were caught up in nor of the violent often metaphorical language of Mao’s increasingly fanatical directives.

After Mao died, when Gua Hafeng, Mao’s successor came to power and finally ended the Cultural Revolution, and when Deng Xiaopeng succeeded Gua, Deng used a show trial (a trial of the so-called “Gang of Four,” which included Mao’s wife, Jiang Qing) to try place blame and make some sort of accounting to the Chinese people. Yet that feeble effort concluded that about 30,000 people had been killed during the Cultural Revolution. Recent research based on primary documents, however, shows that a revolutionary faction that was in power in Guangxi Province killed over 200,000 people in the period of just July through December of 1968 alone. The academic study, “Collective Killings in Rural China during the Cultural Revolution,” estimated that 84,000 people were killed in Guangxi in just two months in 1968. Current independent estimates are very varied and range from the death toll being several million to tens of millions of people who died as a result of the Cultural Revolution, including many of the highest ranking political leaders in the country. By some estimates, the Cultural Revolution was one of the most murderous killings of civilians during formal peacetime.

How could this happen? In the next installment, I’ll try to put the Cultural Revolution in psychological and political context and try to explain how young people could do the things they did.