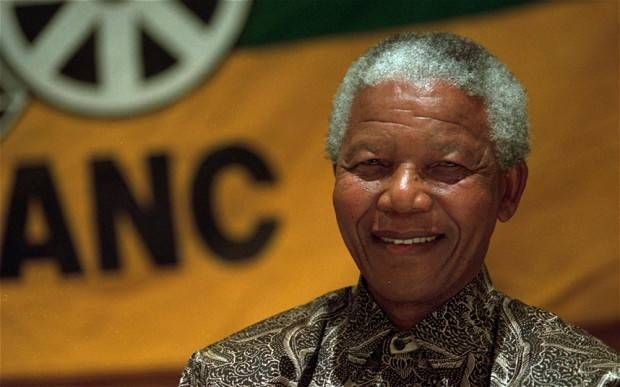

My heart sank once again this morning when I turned on the radio early in the morning to listen to the BBC and the first words over the air were "Nelson Mandela." The reason my heart sank is that every time I hear anything about him these days, I expect to hear that he has died. The news was that he was once again hospitalized with a lung infection that is a complication of tuberculosis he contracted while in prison. Mandela is 94 years old and in declining health. Toward the end of last year, he spent several days in the hospital, the longest stay of his lifetime, and earlier in 2012 he was also hospitalized for a lung infection.

The relatively transparent South African government is uncharacteristically secretive about former President Mandela's health, but his family, including his wife Graca, has said bluntly that Mandela's "spirit and this sparkle, you see that somehow it's fading." During prior hospitalizations, President Zuma has tried to assure the country, but this time, for the first time, Zuma very clearly suggested using a Zulu phrase that the people of South Africa may need to come to terms with Mandela's "homegoing." Mandela no longer makes public appearances. Every hospitalization, obsessively covered by South African media, threatens to be his last, and when he does pass, South Africa is sure to be plunged into a kind of national sincere and heart rending grief for a leader that the world simply hasn't experienced in many decades. Some journalists have commented that when he dies, it won't be as though a former president has died, but that the nation has watched a grandfather, a beloved relative and protector, pass away.

Mandela is one of the most recognized people on the planet and is well known as a personality in the United States. Yet most Americans have little idea of what he actually did, and in the media his formal role in the ANC and his political beliefs are often mischaracterized. Americans often tended to see the South African conflict through the lens of the non-violent US civil rights struggle. Also, during its democratic transition, South Africans had a strong incentive to manufacture a story for export about the "peaceful" transition, so as not to scare off international investment, when it was more like a low intensity civil war. Even well respected American journalists routinely get wrong the basic facts of Mandela’s life and his contribution to the liberation of the country from apartheid, as Bill Keller did last year in an editorial, even though Keller was the New York Times' correspondent in South Africa during the transition.

It probably sounds somewhat incredible to most Americans to argue that they probably don't know who Nelson Mandela is or what he did. But to explain how this is true, consider the following paragraph, a compendium of various ways in which Mandela has been described. Please accept my confession that this is a big fat strawman argument, but it seems the best way to explain my point:

Nelson Mandela was the leader of the African National Congress (ANC), the most important liberation organization in South Africa from the early 20th century until the first elections that allowed black South Africans to vote in 1994. The ANC won the elections and formed a government, and Mandela was the first black president of the country. Before his arrest and imprisonment, he led a campaign of non-violent mass resistance until his arrest and imprisonment on trumped up charges. The ANC's mass action was eventually brutally suppressed when South African troops opened fire at the Sharpville massacre. He served twenty seven years in prison against his will under brutal conditions on the notorious South African prison island, Robben Island, off the coast of Cape Town. When the South African government finally released him from prison in 1990, he was magnanimous toward his jailers, and negotiated the peaceful end of apartheid, the transition to democracy and the new constitution. As president, his stern but grandfatherly demeanor lent great dignity to the office of the South African presidency. After one term as president he retired, setting in place a precedent that in South Africa, president's would leave office at the end of their terms.

I don't think it's an exaggeration to say that this is fairly close to the typical summary of Mandela's life. Most of it is factually incorrect. By trying to explain why it's false, I am certainly not trying to diminish the legacy of Nelson Mandela. In fact, if you continue reading, I hope you'll have even greater respect for Mandela's amazing accomplishments. I just hope that you'll try to understand how much more complex South Africa was and how much more complex the legacy of Nelson Mandela is.

First of all, his name isn't "Nelson"; it's Rolihlahla. His actual name means "pulling the branch of a tree," or more idiomatically, "troublemaker." He acquired the name "Nelson" when he went to a westernized school and had to take a European name.

Second, Nelson Mandela was not "the leader" of the ANC for most of his life, except for a short period from just before he was elected president, until his term ended after five years. He was "a" leader of the ANC when he went to prison, but "the" leaders for most of Mandela's career in politics before he went to prison were more senior men. When Mandela went to prison, the leader, technically "Acting President" of the ANC was a different equally remarkable man who should be better known not only in the US, but in South Africa -- Oliver Tambo. Tambo was Mandela's great friend, law practice partner and political ally. Together they opened the first black law practice in Johannesburg, developing an exceptionally busy and successful practice, handling matters mostly for black clients who otherwise wouldn't have been able to retain a lawyer. Mandela was the courtroom lawyer with razor sharp logic and wit; Tambo was the office lawyer, drafting, negotiating and running the business. When the South African government essentially banned black politics in the early 1960s, Mandela was convicted of several crimes and went to prison while Tambo went into exile. It's possible to imagine the ANC waging and winning the struggle to end apartheid without Mandela; it's not possible to imagine this happening without Oliver Tambo. Tambo built up the ANC from a small group of impoverished exiles into one of the largest liberation organizations in the world, with a small well trained army, intelligence operations, social services bureaus that served the South African diaspora, scholarship programs, and according to some accounts, by the time Mandela was freed, more diplomatic offices than the South African government -- all while escaping a brutal campaign of assassinations against ANC officials carried out by the South African government. Tambo also was a grandfatherly figure who was deeply respected by the exile community and one of the few leaders who could bring together all the different factions of the movement. When Mandela was released from prison and Tambo came back to South Africa from exile, Tambo, not Mandela, was the formal leader of the ANC until he suffered a debilitating stroke and shortly afterward died. Mandela became president of the ANC only in 1991.

One of Nelson Mandela's most important offices was that he was the president of the ANC Youth League, an organization within the organization that he and young men of his age, Walter Sisulu, Tambo, and Congress Mbata, founded in the 1940s to prod the ANC into more Gandhian style direct action. The presidents of the ANC while Mandela was active in the 40s and 50s were Dr. Alfred Xuma, followed by Dr. J.S. Moroka, followed by Nobel Peace Prize winner, Chief Albert Luthuli. Mandela was also responsible for a leadership challenge against Dr. Xuma that caused him to be replaced by Dr. Moroka, an event that Mandela later regretted in his memoir.

With the Youth League in control of the ANC behind the facade of Dr. Moroka, Mandela and his colleagues transformed the organization from a debating and petition writing society to a mass movement. To understand the importance of this, it's necessary to discuss a bit of South African history that most people in the US are not aware of.

The 1994 elections were not the first time Africans in South Africa got the opportunity to vote. Africans in South Africa got a limited voting franchise in 1853 in what was then called the Cape Colony, part of the British Empire, when most African Americans were still slaves. The vote was based on a "colour blind" constitution and a low property qualification that many Africans met because they had adopted commercial farming for the colonial market. Because of the Cape's emancipation of slaves and other liberal policy, many Dutch speaking farmers had broken away from the colony and went into the interior to form Boer republics based on racial discrimination and the conquest of indigenous African kingdoms and chiefdoms (the Afrikaner "Great Trek"). The British Empire fought two wars against the Boer republics (as well as many African kingdoms) eventually culminating in the highly destructive Second Boer War and the incorporation of many polities into a single very large colony, the Union of South Africa. The Cape retained the African and Coloured franchise but it was not extended to other parts of South Africa, and the failure of the British Empire to extend the franchise to the northern provinces of the Union, the former Boer republics, was one of the reasons that Africans founded the South African Native National Congress, which eventually shortened its name to the African National Congress. On the other hand, a South African court handed down a decision analogous to Brown v. Board of Education as early as 1905 (it was captioned Tsewu v. Registrar of Deeds) although politicians soon reversed it by statute. Throughout the early 20th century, white South African politicians relentlessly cut back the Cape African and Coloured franchise, but before 1948, black South African politicians were free to organize and had working relationships with many in the white political leadership. Black South African voters had several members of Parliament who represented the black voting block, like Hymen Basner. That was why people like Dr. Xuma had a very old fashioned approach to black politics -- they had come of age during a period of polite petitions and representations to white political leaders, but by the 1950s, Mandela and his cohort realized that Xuma's style of politics had become hopelessly useless. The history of black South Africa in the first half of the 1900s was the relentless assault on their constitutional and voting rights, and hence they decided to transform the ANC from a small elite organization to a mass organization that carried out mass resistance to unjust laws, especially the pass laws.

In his wonderful memoir, "Long Walk To Freedom," Mandela doesn't however describe himself as a rising star. Although he maintained a great posture of dignity as president, Mandela personally has a mischievous sense of humor; he may be one of the funniest leaders of the 20th century and his autobiography is at times fall off of the chair funny, mostly because of his self-deprecating description of his younger self. Rather than describing the rise of the great man, the autobiography often reads like the memoir of a man who considered himself a country bumpkin in awe of the ANC senior leadership and even of his generational contemporaries like Walter Sisulu and Oliver Tambo. In one passage he describes his comeuppance as a result of challenging Chief Luthuli and a former professor, Z.K. Matthews. The two older leaders had met with several liberal white politicians and Mandela demanded a report back to the younger members. Mandela lashed out:

"What kind of leaders are you who can discuss matters with a group of white liberals and then not share that information with your colleagues at the ANC? That's the trouble with you, you are scared and overawed of the white man...

"This outburst provoked the wrath of both Professor Matthews and Chief Luthuli. First, Professor Matthews responded: 'Mandela what do you know about whites? I taught you whatever you know about whites and you are still ignorant. Even now, you are barely out of your student uniform.'"

Luthuli was also angry and offered to resign, which Mandela says terrified him. Mandela concluded, "I was a young man who attempted to make up for his ignorance with militancy." That is the surprising tone of the memoir - an older man looking back on the ignorant hothead he had often been.

Mandela's other most important formal post before his imprisonment was that he was the founder and head of the armed wing of the ANC, Umkhonto we Sizwe ("Spear of the Nation," usually abbreviated MK). During the period of his last prosecution, Mandela left South Africa and received military training and support in Ethiopia and other African countries. He slipped back into the country and carried out a campaign of sabotage of power pylons, telephone wires, and other infrastructure before being apprehended. He was later prosecuted in his famous "Treason Trial." The charges were, therefore, not trumped up. In fact one of the reasons he came to be so admired is that in his opening statement Mandela confessed to the factual charges in a long speech in which he explained that the ANC had taken the path of armed struggle only because the South African government had made normal politics impossible. So although Mandela started out using Gandhian non violent mass action, he was also a guerrilla leader who theorized that violence was justified under the circumstances.

In other words, Mandela lived through a shift in black politics from polite petitioning, to Gandhian mass resistance to armed struggle. The latter shift was caused in part because the relatively gentlemanly white politicians who governed South Africa from the creation of the Union until the end of World War II were voted out of office and replaced with a party, the National Party, whose leaders had studied in Nazi Germany, were openly fascistic, were opposed to the British Empire's control of South Africa and wanted to strip black South Africans of their remaining rights.

Mandela became as important in prison as he had been outside prison. When he first arrived in Robben Island, the prisoners were subjected to meager rations and hard labor breaking rocks for gravel. Mandela became the de facto leader of the prisoners. Over time through arguing with the wardens and coordinating with colleagues to bring pressure from outside, the prisoners slowly almost took over the prison. Their conditions were improved dramatically, and they began to hold political discussions and educational meetings. I knew one former prisoner who arrived long after Mandela, and who said he enjoyed the lobster dinners! These were not provided by the prison service, but because the prisoners had the run of the island which is surrounded by rich fishing grounds, prisoners would scoop up lobsters from among the rocks surrounding the island for collective dinners. Many prisoners studied for advanced degrees and some prisoners referred to the prison as "Mandela University."

One reason this leadership inside the prison was important is that the ANC was not necessarily the most important liberation organization inside South Africa. The ANC focused on non-racialism and made stringent efforts to form alliances with the mostly white South African Communist Party and Congress of Democrats; the South African Indian Congress; and South African Coloured People's Organization. But waves of prisoners came onto the island who had more racially exclusive ideas, such as members of the Pan African Congress and in the 1970s, the Black Consciousness Movement. Perhaps Mandela's greatest achievement was to convert these younger people to the ANC's non-racial ideology. Because many of them had much shorter sentences, they returned educated by Mandela to the outside to create new organizations that were multi-racial in approach, which in turn, enabled the ANC and its semi legal affiliates (the United Democratic Front and Mass Democratic Movement of the 1980s) to garner wide spread support and ameliorate the fears of white South Africans.

Mandela did not spend all 27 years in prison on Robben Island -- only the first 18 years. Even more remarkably, it's not quite accurate to say he was held in prison against his will. Mandela was offered his freedom several times from around the mid 1970s until 1990 on the condition that he would renounce violence and the armed struggle, but he refused. Mandela made several arguments in response -- including that only the ANC could renounce the armed struggle, which could not happen until they were legalized and able to have a national meeting to decide the issue; in the meantime as a disciplined member of the ANC he could not unilaterally renounce ANC policy. He also argued that the ANC could only renounce violence when the government also renounced violence. Some high profile prisoners took the offer of release in exchange for renouncing armed struggle, but Mandela never did, and as a result, stayed in prison for an additional 15 years on principle. It was that iron discipline and principle that gave him the greatest credibility among all political leaders among black South Africans outside prison facing daily violence from the regime.

Nevertheless during the latter part of his stay, he and his colleagues came to be treated more and more almost like a government in waiting. In 1982 he was transferred along with the senior leadership of the ANC to Pollsmoor Prison on the mainland where they were able to meet, read, correspond with the outside world and receive visitors. The relatively benign prison authorities at Pollsmoor allowed Mandela to create an extensive rooftop garden where he was so successful growing vegetables for himself and especially for the under privileged non political prisoners that it had a marked improvement on their diets, and he even sent sacks of vegetables home with his working class prison guards for their families.

In the mid 1980s, the prison authorities surprised Mandela by beginning to take him on trips outside the prison around Cape Town. Mandela liked to stare at people and therefore invite them to stare back to see if they recognized him. But he looked nothing like the heavyset young amateur boxer who went to prison and was by the 1980s, a tall gaunt white haired man. No one ever recognized him on trips to restaurants, beaches, or gardens. (When Mandela was first released several of my friends adopted a conspiracy theory that that man wasn't Mandela, looked nothing like him and was a double intended to sell out the movement; of course Mandela's friends and associates who had been in touch during all those years vouched that this tall thin man really was Mandela.) Mandela even attended dinner parties at the homes of senior prison officials. In his memoir he tells a funny story about the warden leaving him alone in a car on a street in Cape Town to buy a soft drink and Mandela wondering whether he should just walk off into freedom; but after a few minutes of panic, he chose to stay.

Sometimes Mandela is described as having negotiated the new constitution and transition of power. This is not really the case. After Mandela was finally released in early 1990, and constitutional negotiations began in earnest, contemporary news reports described him as being generally disengaged from the constitutional negotiations. They were very complex involving hundreds of lawyers and academics and were overseen by two other men -- for the ANC, Cyril Ramaphosa a brilliant labor lawyer and head of the National Union of Mineworkers and then the giant trade union federation, the Congress of South African Trade Unions, and for the government, Roelf Meyer, a former intelligence chief. They so dominated the drafting of the constitution (and became such fast friends) that the newspapers began referring to the talks as "The Cyril and Roelf Show." Both Mandela and president F.W. de Klerk kept their distance -- it was alleged because the constitutional compromises would likely be very unpopular and it was better for Mandela and de Klerk to save their political capital for selling the unpleasant deal to their constituencies rather than spending it on the legislative sausage making.

Mandela, however, did play the primary role in getting "talks about talks" going while he was still in prison. In the late 1980s, he wrote several letters to the director of prisons who finally began setting up conferences with other high level government representatives. Mandela's main great accomplishment was opening the dialogue and then persuading his fellow prisoners and the ANC in exile to allow him and these government officials to create a framework for his release and the unbanning of the ANC.

Eventually Mandela accepted a compromise -- to "suspend" the armed struggle but not unilaterally abandon it. What happened, however, was that political violence spiraled out of control and South Africa experienced a terrible civil war. The ANC continued to use at least defensive armed struggle until a final constitution was approved and elections held. By then, the ANC and the South African government had formed an alliance against various extreme, armed, right wing parties that wanted to prevent the elections. Although the ANC won the election, the government was a coalition government of the ANC and its former enemies, the National Party.

Update: Corrected for grammar, spelling and clarity. And thanks for the Community Spotlight!