In October 1983 the largest military power in the world, the United States, invaded one of the smallest countries on the planet, the tiny Caribbean island of Grenada--a country with a population smaller than Dayton, Ohio, and a military smaller than the New York City Municipal Police Department.

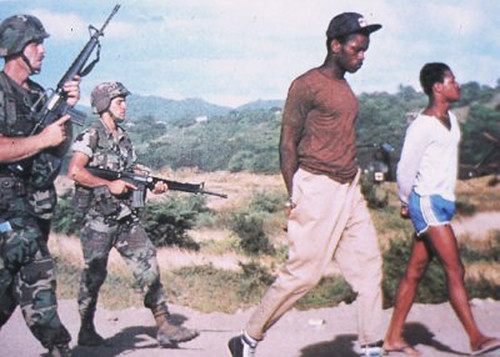

US troops with captured Grenadians. US Defense Department Photo

The tiny island of Grenada, located in the Caribbean near Barbados, was a British colony until it was granted independence in 1974. In a struggle for power, Sir Eric Gairy, a former Premiere with the colonial government who had led the drive for independence and who now headed the Grenada United Labour Party, faced off with the more radical group led by London-educated lawyer Maurice Bishop, leader of the New Joint Endeavor for Welfare, Education and Liberation ("New Jewel") Movement. At times, the election became a street fight, with Gairy's private army, a militia known as The Mongoose Gang, mixing it up with militia members from the New Jewel Movement. When the elections were held in 1976, Gairy claimed victory, but Bishop refused to accept the legitimacy of the election, and called for Gairy's overthrow.

Bishop was a talented speaker and organizer, and won the support of a large part of the population on Grenada. And his leftist Marxist-Leninist rhetoric earned him the support of Cuban leader Fidel Castro, who secretly began to funnel money and guns to the New Jewel Movement. On March 13, 1979, they got their chance--as Gairy was out of the country on a state visit, armed members of the New Jewel Movement seized power in a coup. Bishop was declared as the Prime Minister.

Once in power, Bishop established diplomatic ties with the Soviet Union and Cuba. The new People's Revolutionary Government won wide support among the population as it imported Cuban doctors and established a first-class medical system, carried out a program of land reform by seizing large landed estates, breaking them into pieces and giving them to poor individual farmers, and began investing large sums of money into improving the island's infrastructure to attract a tourist trade, including continuing the construction of a new airport already planned by the British colonial government and begun by Gairy after independence, big enough to handle 747 jumbo jets, at Point Salines. Castro's government sent a group of construction workers to help with the project, who, as members of the Cuban militia, also acted as security.

Bishop needed the security. The 1980s marked a new peak in the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union, as newly-elected President Ronald Reagan condemned the "softness" of the previous administration and announced that the US would carry out an unprecedented peacetime buildup of its military forces to counter the Soviet "evil empire". Although Grenada was barely one hundred square miles and posed no realistic military threat to anyone, the Reaganites focused on Bishop's Marxist rhetoric and his ties to Cuba and the USSR, and decided that the tiny island would make a good demonstration of the New America, dedicated to flexing its diplomatic and military muscles to oppose the Soviet Union globally. Most of all, Reagan wanted to end the "Vietnam Syndrome"--the marked reluctance of the American public to engage in military ventures abroad after the humiliating debacle in Vietnam and the equally humiliating hostage saga in Iran during the Carter years. In Central America, the administration was already funneling guns and money to repressive military regimes in El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras who were facing leftist guerrilla insurgencies; in Nicaragua, where the leftist Sandinista guerrillas had overthrown the US-backed dictator Somoza, the US was arming and financing the "Contra" anti-government insurgents. In Grenada, Reagan saw a small but symbolic target that the US could stomp with impunity, demonstrating its new willingness to use its power to take a hard line with the Russians in the Cold War.

Throughout the early 80's, the Reagan administration acted to oppose the Bishop regime, nudging the other Caribbean countries to sever ties with it and enticing the international finance system to cut off its credit. This, ironically, drove Grenada into even closer economic ties with the Soviet Bloc. In March 1983, during a speech, Reagan charged that the Point Salines airport was actually being planned as a Soviet airbase for Russian and Cuban cargo planes and, perhaps, fighters and bombers, with the intent of threatening US shipping lines to Europe in the event of World War Three. Although Reagan's claim was widely ridiculed in the US by Democrats and peace activists who opposed his policy of militarization, it became an article of faith among right-wing hardliners.

The island's major source of foreign exchange funds, however, remained the St George's Medical Center, a privately-owned medical school that took in students, mostly from the US, who had failed to be accepted at their own country's medical schools. By 1983, the school had over 1,000 students located at two campuses.

The American medical students became a central focus for the US when, on October 16, 1983, Bishop's government became the target of an armed coup by a faction of the New Jewel Movement led by Deputy Prime Minister Bernard Coard, who viewed Bishop as too accommodating to the United States. Bishop was placed under house arrest but, with significant popular support, he was able to escape and evade Coard's forces for several days before again being captured and executed. In the ensuing chaos, another group of Grenadian Army officers, led by General Hudson Austin, stepped in and seized power, ruling through a military council, which immediately imposed a 24-hour curfew and announced that anyone on the streets would be shot.

The Reagan Administration viewed the coup with alarm, which was heightened when, on October 23, a truck bomb at a US base in Lebanon killed over 240 Marines. Reagan thought he now faced a real threat of similar chaos in Grenada, compounded by the presence of over 600 American medical students on the island--although they had not been harmed or threatened in any way, Reagan considered them as potential hostages for the new "revolutionary government". That would be a political disaster. So Reagan gave the order for a military intervention to evacuate the medical students and to establish a stable pro-US government on the island. As diplomatic and legal cover, Reagan pointed to a series of requests from the Organization of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS) for the US to intervene and establish order in Grenada.

At first, the planning was for a small Special Operations group to enter the island at night, locate and evacuate the American and other foreign civilians, and neutralize the military government and replace it with elected civilian rule. For various reasons, including inter-service rivalry and bureaucratic requirements, the operation grew to involve regular troops and ships from the Army, Navy and Marines. On October 25, 1983, the first of what would eventually be 7,000 American troops, accompanied by a token force of soldiers and police from Barbados and other Caribbean nations, landed at dawn on Grenada. They were opposed by 600 Cuban construction workers (who were also militia members) and 1500 troops from the Grenada Army.

The operation was bungled from the start. The short notice and quick deadline meant that planning was sacrificed in favor of speed. The Reaganites were paranoid that if the Grenada forces found out the invasion was coming, they would take the students hostage--so they kept the entire operation secret even from some of their own military commanders. Intelligence information on the island was nonexistent; nobody even knew if US cargo planes could physically land at Point Salines airfield. There was no clear sense of who was in charge of the operation, the Navy or the Army. The communications equipment used by each service was incompatible with the others; in one famous instance, a US Army trooper in Grenada had to use his ATT calling-card to phone his wife at Fort Bragg in the US to request an air-support strike from the Navy. Medical support came from the Navy ship USS Guam, but Army helicopters carrying wounded could not directly radio the ship, and when they got there, they found that Navy refueling equipment was incompatible with theirs.

In the end, the sheer weight of American military power was decisive, and combat lasted less than a week. The Point Salines airport was seized, the medical students were located and evacuated to Barbados, the prisoners being held by the military council were released, and the coup leaders were arrested. A total of 19 American troops were killed, along with 29 Cubans and 49 Grenadians. In the aftermath, the former British governor Paul Scoon was installed as temporary head of government.

Diplomatically, the invasion provoked a storm of protest. One of the loudest came from Britain's Margaret Thatcher, who considered Grenada (a member of the British Commonwealth) as her responsibility. The UN General Assembly passed, by a vote of 108-9 (with 27 abstentions), a resolution condemning the US's "flagrant violation of international law". A similar resolution in the UN Security Council was vetoed by the United States. In the US, a demonstration against the invasion in Washington DC attracted 30,000 people (the diarist was there, in what was the first of what would be many subsequent anti-war demonstrations I attended over the years).

"Operation Urgent Fury" left the US with a long-lasting legacy that still is felt today. Psychologically, the quick victory in Grenada ended the "Vietnam Syndrome", opening the door for American military interventions in Panama, Iraq, and Afghanistan. Diplomatically, the Grenada invasion established the US policy of unilateral American pre-emptive intervention in any area it considered a threat, regardless of the opinion of the international community. And in Grenada, which was one of the poorest nations in the Caribbean, the invasion produced nothing. The Americans packed up and left without providing any economic aid for Grenada. When the 2007 Cricket World Cup was held in the capitol city of St George's, the new $40 million stadium was built with funding from China.