Appalachia is a large geographic region in the eastern United States with a distinct cultural and demographic identity. What if this region were a single big state instead of split several ways between largely non-Appalachian states due to circumstances of American history? In 2013, I explored the political impact of such a scenario, which revealed how Appalachia would have long been a key swing state but has since zoomed to the right over the last two decades, culminating in Barack Obama losing there by 24 points in 2012. The recent conclusion of the 2016 presidential primaries in Appalachia provides a new opportunity to examine the region’s politics.

There is no consensus on Appalachia’s geographic definition, but one such version as seen above contains 311 counties or county-equivalents across parts of 11 states, which of course means 11 different election procedures. Some of these states used open primaries, some used closed, while West Virginia’s primary even occurred after Donald Trump’s major opponents dropped out. Thus, comparing election outcomes across 11 different states isn’t a perfect apples-to-apples equivalent, but it still provides some useful insights.

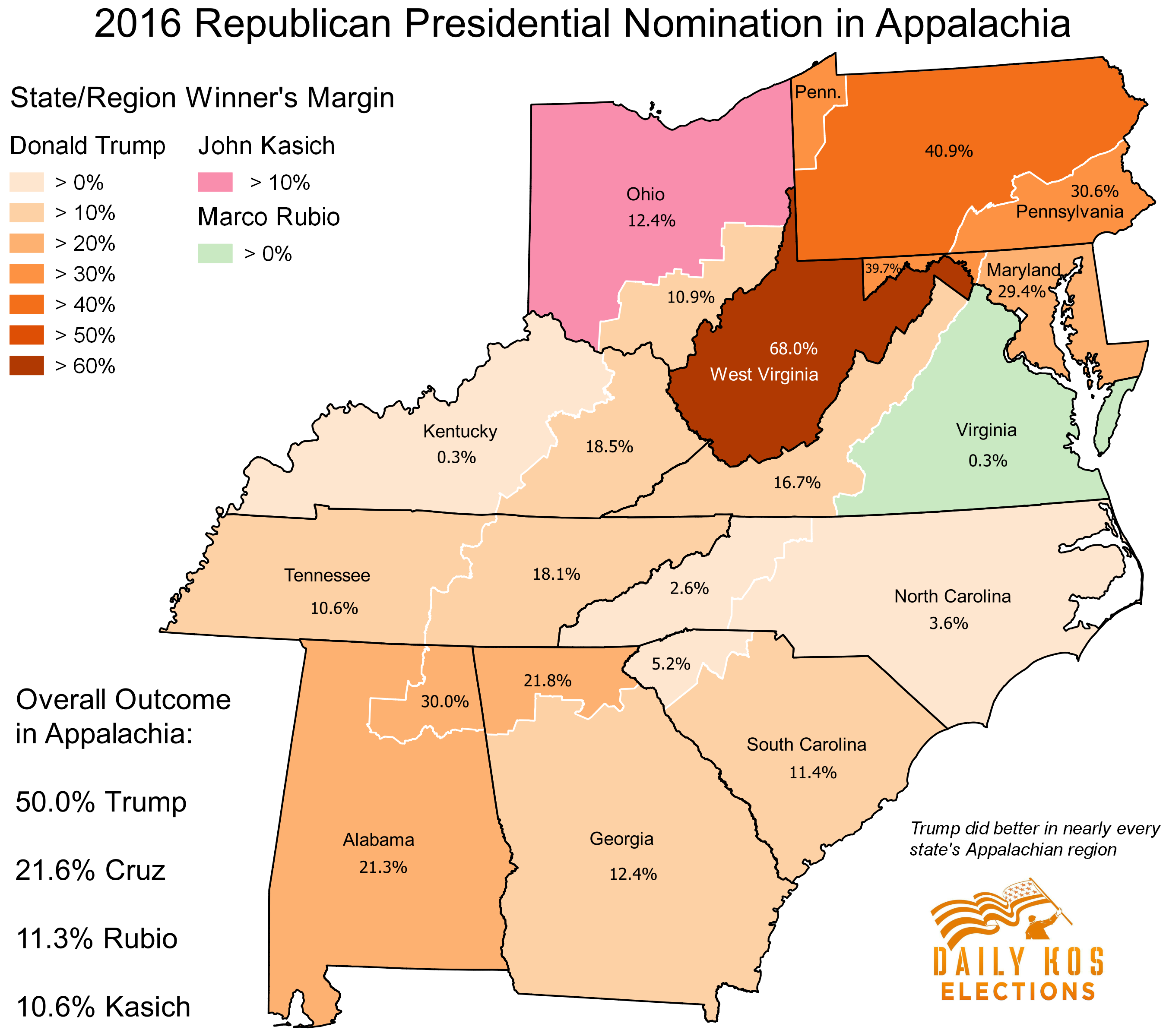

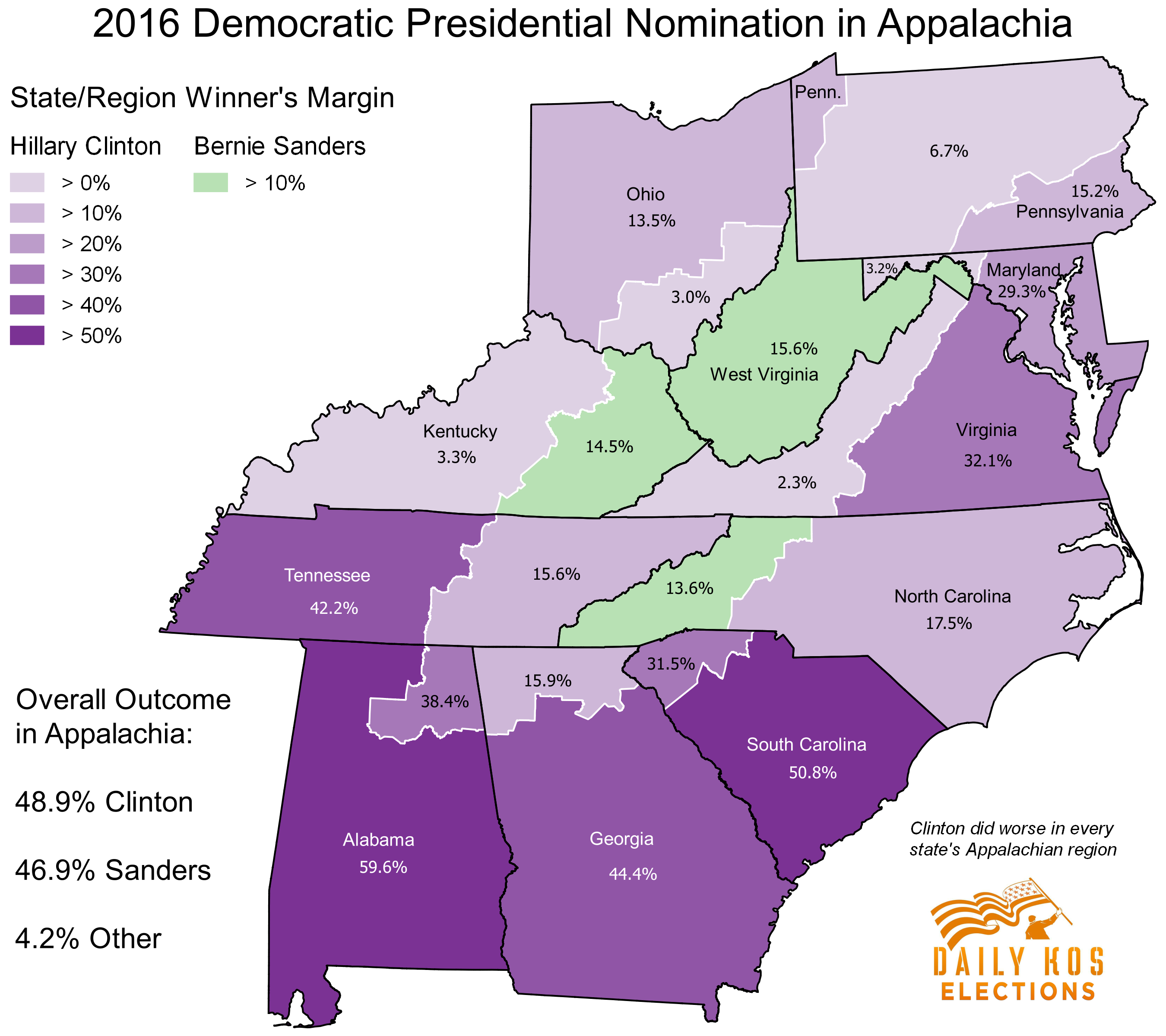

Trump won a complete landslide in the region and carried 295 county units. He performed nearly 10 points better in Appalachia than he did nationally and narrowly won an outright majority of the vote against badly-divided opposition. Hillary Clinton, on the other hand, barely eked out a plurality of 49 percent to 47 percent over Bernie Sanders despite leading him by nearly 14 points in the national popular vote to date. That stands in sharp contrast to Clinton’s dominance in 2008, when she crushed Obama by 32 points in Appalachia, and it would have been her fourth best state or territory nationally that year.

Appalachia existing as its own primary state would have altered the dynamics of both races by reshaping campaign strategies of where and when to allocate resources. Given the closeness of the Democratic race across the whole region, Sanders likely would have devoted more resources to winning it instead of largely ignoring several southern states, which comprise a significant share of Appalachia. The surrounding states losing their Appalachian regions changes their politics too, and that would have resulted in different outcomes in some. Let’s investigate these results in more detail.

Click to enlarge

Click to enlarge

Trump prevailed in the Appalachian region of all 11 constituent states. His best regions were the states that went later in the primary calendar: Maryland, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia. His narrowest victories were in the Carolinas, with the smallest being just a 2.6 percent win over Ted Cruz in Appalachian North Carolina.

Trump won by a larger margin in the Appalachian region than in the rest of each state in every contest except for in the Carolinas. While Trump carried all of these states except Ohio, Marco Rubio actually would have won Virginia without its Appalachian region by a narrow 0.3 percent. Cruz would have come up just shy of winning the Kentucky caucus without Appalachia by a similar 0.3 percent margin. Although John Kasich easily won his home state of Ohio, Trump carried the Appalachian segment of it by low double digits.

Click to enlarge

Click to enlarge

Trump utterly dominated at the county level, too. He only lost a few places which tended to have relatively more-educated voters like the college town of Lexington, Virginia, and the liberal enclave of Buncombe County, North Carolina, home to Asheville. That isn’t surprising since opposition to Trump was highest among Republicans with higher levels of education. Trump even came close to sweeping every county in Ohio despite it being Kasich’s home state and Kasich dominating in non-Appalachian Ohio.

Trump won Appalachia’s biggest population center around Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, in a landslide, but he also carried the other two biggest population centers of Knoxville, Tennessee, and Greenville-Spartanburg, South Carolina, by narrower margins. While Trump generally performed by similar margins throughout each state’s Appalachian region, he was much weaker in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley than in southwestern Virginia, which like neighboring eastern Kentucky and southern West Virginia maintains more of a coal country influence on its politics.

Overall, Trump’s best county was McDowell, West Virginia, where he won 91.5 percent, His worst was the independent city of Lexington, Virginia, home to Washington and Lee University, where Rubio won with 44.3 percent and Trump was exactly tied with Kasich for second place with just 19.9 percent.

Click to enlarge

Click to enlarge

The Democratic primary exhibited an even starker division between each state’s Appalachian and non-Appalachian regions. While Clinton won every state except West Virginia, she performed worse in every state’s Appalachian region and Sanders easily won Appalachian Kentucky and North Carolina. Sanders also came very close to victory in Appalachian Maryland, Ohio, and Virginia despite Clinton easily winning the remainders of those states. Clinton won by a comfortable margin in southern Appalachia outside of North Carolina, but still performed dramatically worse than in the rest of those states.

These disparities between the Appalachian region and the rest of each state are largely a function of demographics. At 88 percent white according to the 2010 Census, Appalachia is far whiter than the surrounding states. This disparity is especially stark in the Deep South states where the Democratic primary electorate was majority African-American. Nationally, Clinton has performed very strongly with black voters while Sanders does far better with white voters.

Given Sanders’ relatively much stronger performances in each state’s Appalachian region, he likely would have invested campaign resources in southern Appalachian states such as Alabama and Georgia rather than ceding them entirely to Clinton. Whether Sanders’ increased campaign spending there would have moved enough votes to overcome Clinton’s two point victory is impossible to tell, but it isn’t an implausible outcome.

Of course, since the Democratic primaries awarded delegates relatively proportionally, whether or not Sanders could have won Appalachia overall with different strategic decisions makes little difference to the ultimate nomination outcome.

Click to enlarge

Click to enlarge

Clinton and Sanders each won close to half of Appalachia’s counties and independent cities. Clinton prevailed in 168 while Sanders carried 143. Just like Trump, Clinton carried the three most populated areas with a comfortable win in greater Pittsburgh, a narrow win around Knoxville, and a landslide in Greenville-Spartanburg. Also similarly to Trump, Clinton was typically weak in college towns and western North Carolina.

Clinton’s best county was Cherokee, South Carolina, where she won 77.9 percent to 21.3 percent, while Sanders’ best county was Floyd, Virginia, which he carried 70.1 percent to 29.6 percent.

Clinton’s worst region was the coal country of Kentucky and West Virginia, where a very large proportion of the electorate consists of registered Democrats who vote Republican in November. In a closed primary, many of these conservative Democrats voted for Sanders not because they supported his ideology, but because they associate Clinton more closely with Obama, who is extremely unpopular there. This pattern didn’t extend just over the border to southwestern Virginia, where Clinton easily won—and to a large degree that’s because Virginia held an open primary.

Click to enlarge

Click to enlarge

Appalachia is also unique because of the number of Democratic primary voters who chose candidates other than Clinton or Sanders even though they were the only two major candidates. Minor candidates won a larger share of the vote in the Appalachian region within most states and this difference was particularly acute in Maryland and Kentucky. Minor candidates also did extremely well in West Virginia and Appalachian Kentucky in the 2012 primary, even though Obama had no major opposition.

Much of this stems from the same phenomenon driving conservatives to vote for Sanders: closed primaries. In Kentucky, West Virginia, and the Appalachian region of other states there are many voters who voted Democratic for decades until the last several elections. Many of these voters haven’t switched their party registration to reflect their longstanding conservative ideology and newfound tendency to vote Republican. When primaries aren’t open, these registered Democrats became stuck with two options whom they both disliked.

Alabama, Kentucky, Maryland, and Pennsylvania all held closed primaries on the Democratic side, while North Carolina and West Virginia held semi-closed primaries where independents could pick whichever party’s primary they preferred, but those registered with a party could only vote in that party’s nomination contest. Georgia, Ohio, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia held open primaries.

In 2012 Mitt Romney beat Obama in Appalachian Kentucky by more than 46 points, but in 2016 Democrats still hold a 49 percent to 46 percent edge over Republicans among registered voters there. Romney carried West Virginia by nearly 27 points, but Democrats maintain a 47 percent to 30 percent voter registration edge. Since those two states have seen some of the sharpest swings to the right in recent presidential elections, that leaves them with a huge disparity between party registration and actual party preference.

Click to enlarge

Click to enlarge

Minor candidates won a dramatically higher share of votes in particular counties (note the different scale on this map). In Mingo County, West Virginia along the Kentucky border, minor candidates collectively won more than 30 percent of the vote. A relatively-unknown West Virginia resident won 23.7 percent there and actually beat Clinton for second place. Clinton’s 21.4 percent there was her lowest support of any county in Appalachia. Mingo is in the heart coal country and both it and nearby counties in both Kentucky and West Virginia have massive Democratic registration advantages despite voting for Romney in a landslide in 2012.

Again, thanks in large part to Virginia’s open primary, minor candidates did very poorly even in counties like Buchanan, which borders both Kentucky and West Virginia and shares similar demographics with those states. Interestingly, Appalachian Pennsylvania had relatively few votes for minor candidates despite its closed primary, even in the counties bordering West Virginia. However, while it has a disparity between registration and election results, it isn’t nearly as large in as either Kentucky or West Virginia. Romney won Appalachian Pennsylvania by just 8 points and the Democratic registration edge there is also just 8 percent.

Changes in party registration typically lag changes in self-identified partisanship and there is a strong likelihood that minor candidates will continue to win a non-trivial share of the vote in future Democratic primaries, particularly in West Virginia and eastern Kentucky.

Clinton’s overall two-point victory in Appalachia was a dramatic reversal of fortunes from 2008. Her 15 percent collapse in vote share would make Appalachia her fourth worst decline among all the states and territories thus far. The only worse declines were in Oklahoma, which like West Virginia has a large disparity between party registration and voting habits; Utah, which switched from a primary to a caucus (where Sanders typically fares much better); and Vermont, which was Sanders’ home state.

On the other hand, Clinton performed far better in 2016 compared to 2008 in many of the states surrounding Appalachia (such as Georgia) thanks to those states having a much higher proportion of minority voters. These swings are emblematic of the national primary outcome, where Clinton has far more support among black voters and relatively weaker support among white voters compared to 2008. Thus it should come as no surprise that Clinton has fared worse in Appalachia given that the region is so heavily white.

Overall, Appalachia’s voting patterns stand in stark contrast to its neighboring states in the primaries for both parties. Thanks to its differences in racial demographics and educational attainment levels, these disparities are likely to continue in future primary elections.