At the moment, Hillary Clinton maintains a strong 8-point lead over Donald Trump in national polls. Meanwhile, Democrats have a good chance of gaining the four seats they would need to regain control of the Senate chamber if Clinton wins, since a Vice President Tim Kaine would be able to break ties. But while election analysts of all stripes have long viewed the battles both for the presidency and Senate as competitive, many have assumed that the fight over the House of Representatives would not be—at least until Trump’s unique toxicity began testing that proposition. So why have prognosticators generally been down on the Democrats’ chances of gaining the 30 seats they’d need to wrest the speaker’s gavel away from Paul Ryan? That’s what we’ll explore.

Congressional district lines are one of the most important reasons. Despite recent court-ordered redistricting in Florida, Virginia, and North Carolina, 224 congressional districts voted for Mitt Romney and just 211 for Barack Obama, even though Obama won the national popular vote by 3.9 percent in 2012. If we ranked every district from reddest to bluest according to how they voted in the last presidential election, the median seat—the one that would get Democrats a bare majority of 218 if they won every seat bluer than that mid-point seat—you’d land on Arizona’s 2nd District, which Romney carried by a margin of 1.6 percent.

If you could imagine every district in American shifting exactly in step with every change in the national presidential vote (it wouldn’t, but this concept of a “uniform shift” is still helpful in thinking about this problem), Obama would have had to win the popular vote by 5.5 percent just to carry half of the districts in the House. In other words, with a 1.6 percent bump in the popular vote, Obama would have theoretically carried Arizona’s 2nd, just barely turning it blue. And in this polarized era, another 1.6 percent of the vote is a lot to ask for.

Correlation of 2012 congressional and presidential election results by district

Correlation of 2012 congressional and presidential election results by district

This bias is crucial for Republicans because split-ticket voting is at historic lows: Few voters now cast their ballots for one party for the presidency but for the other party for congressional races. As a result, presidential election results are extremely correlated with congressional election results. In 2012, just 26 of 435 districts, or 6 percent, sent a Democrat to the House but voted for Romney, or elected a Republican but went for Obama. So if voters are mostly voting a straight ticket, and most House districts favored Romney, then you’re simply going to wind up with more Republicans than Democrats in the House.

Remarkably, House Republicans didn’t only overcome Obama’s 4-point win in 2012. That same year, the combined vote for all House candidates nationwide favored Democratic candidates by a 1.2 percent margin, so winning a majority of votes doesn’t translate into a majority of seats. And looking toward 2016, even if Democrats somehow won all 28 Obama districts that Republicans currently hold, they’d still fall short of taking control of the House.

So why is the playing field this biased, and how big of a margin in the House popular vote would Democrats likely need to win the House? Let’s take a look.

There are two key reasons districts are so tilted toward Republicans, though one is far more crucial than the other. First, Democratic voters are typically more geographically concentrated than Republicans. Districts comprising inner cities overwhelmingly vote Democratic while many suburban and rural seats lean Republican by much more modest margins. Consequently, Democrats get packed into a smaller number of districts which, on average, are considerably bluer than Republican districts are red. This means that Democrats “waste” more votes than Republicans do, giving the GOP a natural advantage. (You can see this illustrated in the chart just above.)

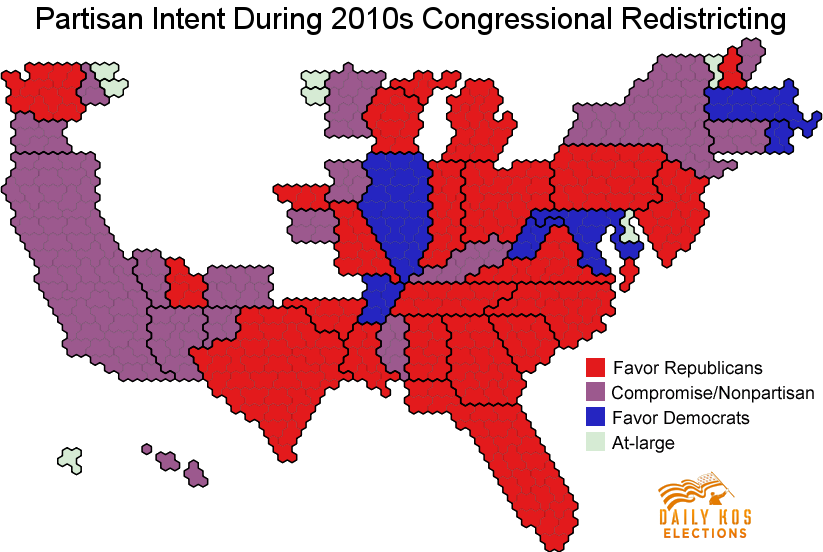

Equal-area district map of partisan intent by state in the 2010 congressional redistricting cycle

Equal-area district map of partisan intent by state in the 2010 congressional redistricting cycle

However, some analysts vastly overstate the importance of geography compared to the main culprit: gerrymandering. As a result of the 2010 Republican wave, the GOP took over state legislatures and governorships all across the country. When it therefore came time to draw new congressional districts following the decennial census, Republicans got to play cartographer for 55 percent of House districts nationwide; Democrats, by contrast, only wielded the mapmaker’s pen in 10 percent of seats (the rest were produced by nonpartisan panels or were the results of compromises in states where power was divided between the two parties).

As we outlined in a series of articles last year, Obama and House Democrats likely would have won a majority of districts in 2012 had there been no gerrymandering at all by either side (or more realistically, had nonpartisan authorities drawn every map). But fairly or unfairly, we have to contend with the gerrymandered districts we've got.

Polling trend for the national congressional generic ballot

Polling trend for the national congressional generic ballot

One way we measure the standing of both parties in the fight for House control is through generic congressional ballot polls, which don’t try to test actual candidates. Rather, pollsters conducting national surveys will ask respondents questions like, “If November's election for Congress were held today, which party's candidate are you more likely to vote for in your district?” We often use these results to approximate where the final House popular vote result might wind up. Currently, Democrats lead on this question by around 7 percent in the Huffpost Pollster average, but such pollsters ask questions on this topic much less frequently than they ask about presidential matchups, making us less confident in these numbers. Still, they can be a useful guide.

As we noted above, Democrats won the House popular vote by 1.2 percent but only won 201 seats, or 46 percent in 2012. One way we can estimate how big of a House popular vote margin Democrats would need in 2016 is to apply the uniform swing model we discussed earlier, except this time, we’ll look at the actual results of each House race for each district, rather than the presidential results in each seat. In other words, if we ranked every congressional election from least to most Democratic, and every seat swung toward Democrats by the same percentage, how big would that swing have to be for Democrats to take a majority?

In 2012, the median seat by this metric was North Carolina’s 9th District, which Republicans won by 6.3 percent. That’s considerably redder than the median presidential district that we described earlier (Arizona’s 2nd), and it means that Democrats would have needed to expand their 1.2 percent margin in the House popular vote all the way to 7.5 percent for just the barest majority when applying a uniform swing.

Of course, uniform swing isn’t a perfect model, because some districts are outliers thanks to multiple factors. Broadly speaking, not all districts have the same characteristics: Some segments of the electorate are more prone to swinging between the parties or are more likely to see disparate turnout levels between election cycles, and the composition of each district is going to be different.

There is also the matter of incumbency: Parties are almost always more likely to win if their current officeholder seeks re-election, but the roster of open seats changes every cycle. Although increasing polarization has decreased the value of incumbency, it still creates a very real advantage. Name recognition plays a big role for incumbents, and they often maintain large fundraising advantages that allow them to dominate the public conversation in the heat of the campaign.

Incumbency gives Republicans an even further advantage because two years ago, they won their largest House majority in any election since before the Great Depression, taking 247 seats. While 25 GOP members are retiring or seeking another office, the vast majority aren’t. Democrats, in other words, will have to contend with a lot of entrenched Republican incumbents, and that includes swing districts that might otherwise be predisposed to supporting Democrats in an open-seat race.

Incumbency also wreaks havoc with national generic ballot polls, because voters might prefer one party in the abstract but ultimately wind up voting for the other party simply because of who their district’s incumbent is. Therefore, we shouldn’t be surprised if Democrats’ popular vote margin ultimately underperforms the generic ballot polls by a modest amount. However, it’s worth noting that Democrats actually slightly overperformed their 2012 generic ballot polling, but that should be expected when the party also won by more than the polls predicted in the presidential race that year.

Complicating matters further, Democrats might not improve on their previous results uniformly. For instance, if they do better in heavily Republican districts but still lose, or run up the score in Democratic-held seats they were going to win anyway, that improvement will show up in the final House popular vote tallies—but it won’t help the party increase its seat share in Congress. This adds additional uncertainty to the overarching question of what House popular vote margin would be necessary for a Democratic majority, because Democrats really need is to improve enough in winnable Republican-held districts.

Note: Some states don’t put the election on the ballot at all if one candidate is unopposed

Note: Some states don’t put the election on the ballot at all if one candidate is unopposed

One final factor that affects the House popular vote compared to the generic ballot is uncontested seats. In 2016, one in seven congressional districts lacks candidates from both major parties on the ballot. Running for office is a costly venture and oftentimes parties simply won’t field candidates at all in seats they can’t win. Other states, most notably California, can wind up with two candidates of the same party in the general election, thanks to the use of the so-called “top-two” primary. Come November, the winning party in districts like these can win hundreds of thousands of votes while the party without a candidate wins zero.

These seats can thus skew the national popular vote result compared to what we might expect from the generic congressional ballot polls, because a voter might tell a pollster she plans to vote for a Democrat, say, only to find out that there’s no Democrat on her ballot.

If we use a simple model to estimate what the effect of this “missing candidate” skew is, Democrats might have expanded their House popular vote margin from 1.2 points to closer to 2 points had both parties fielded at least a token nominee in every district. That would have barely changed the outcome in terms of seats that year, but it means that the generic ballot could overstate the House popular vote total Democrats can expect to end up with. Fortunately (for analysts, not for democracy), both parties left a similar number of seats uncontested in 2016, so this factor is less likely to distort the outcome to the extent it did in wave elections like 2006 or 2010.

Of course, the biggest elephant in the room is Donald Trump. Election analysts have been intensely debating whether he could shake up the traditional electoral map, and if so, by how much and in what ways. Polls consistently find Trump performing much better with non-college educated white voters, particularly men, than Romney did relative to his national performance. At the same time, they also find Trump uniquely weak with college-educated whites and with minority voters. If this trend holds in November and filters down the ballot, congressional seats might swing in a decidedly nonuniform way.

For instance, Democrats might be able to win Republican-leaning seats that previously looked safe for Team Red, like Minnesota’s heavily suburban and highly educated 3rd District. On the other hand, Democrats might have a harder time picking off more heavily white working-class districts that had looked like prime offensive opportunities earlier in the cycle, like Maine’s rural 2nd District.

It’s difficult to predict how these trends could affect the precise House popular vote margin Democrats need to win the House, but it’s possible that the median district according to the 2016 presidential results won’t be as Republican-leaning as it was after 2012. Furthermore, Trump’s radioactive persona and his ideological divergence from Republican orthodoxy could lead to a geographically uneven increase in ticket-splitting compared to previous elections. So far, though, Democrats are faring well even in downballot polls.

House election results have become increasingly correlated with presidential election results in recent years

House election results have become increasingly correlated with presidential election results in recent years

Analysts at FiveThirtyEight, Larry Sabato’s Crystal Ball, the Princeton Election Consortium, and elsewhere have tried to come up with estimates for the House popular vote margin Democrats might need based on recent elections. However, comparing 2016 to previous elections when Democrats won majorities, even those as recent as 2006 or 2008, is a fraught exercise because split-ticket voting has declined sharply and gerrymandering has grown more potent than it was just a few cycles ago. In years like 2006, Democrats could count on winning over many rural moderate and conservative white voters, particularly in the South, but the experience of the intervening years suggests that’s exceedingly unlikely in 2016.

So when it comes down to it, we really can’t say with much precision what popular vote margin Democrats need to win the House in today’s environment, but 7 to 8 percent seems reasonable. What we can say with confidence is that, if 2016 is anything like the polarized elections of 2012 and 2014, Democrats could need a true wave election like 2006 or 2008 for a majority. That margin could be difficult—but Donald Trump just might make it possible.