Migration involves both push and pull factors. For the Chinese who came to the Americas, the push factors included political turmoil and economic instability in China as well as increased population, natural disasters, the opium wars, and the corruption of the Ch’ing Dynasty. The initial pull factor was the California gold rush. Between 1850 and 1880 more than 300,000 Chinese came to the United States.

Like many Western towns, The Dalles, Oregon has a Chinese heritage which is no longer visible. Chinese began moving into The Dalles in the 1860s, and by the 1880s there were a number of Chinese merchandise stores. By 1880, there were 9,510 Chinese living in Oregon and 116 in The Dalles. Today, however, The Dalles Chinatown is almost forgotten. One gallery in the Wasco County Historical Museum is dedicated to telling the story of the Chinese people who once lived here through archaeology and history.

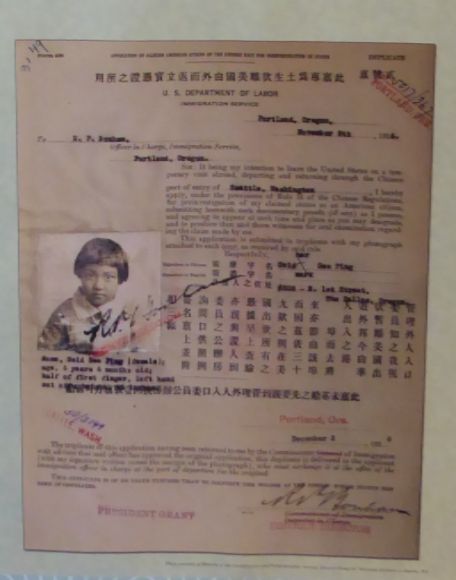

The Chinese Exclusion Acts of 1882 and 1892 restricted the immigration of the Chinese. Chinese had to obtain and carry with them at all times a certificate of identification as proof that they were legally in the country. According to the Museum display:

“Enforcement of the act, and an increasingly complex immigration policy, necessitated the creation of an entirely new federal agency, the Office of the Superintendent of Immigration. The agency’s regional office in Portland occasionally sent Inspectors to The Dalles to check the registration of Chinese residents, investigate their travel requests, and inspect their mercantile stores.”

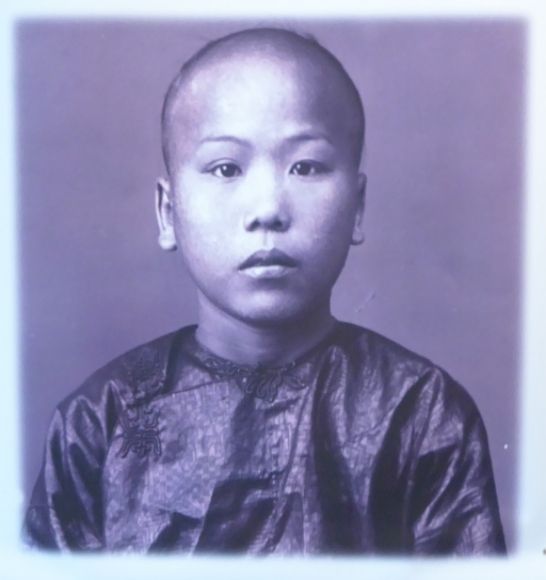

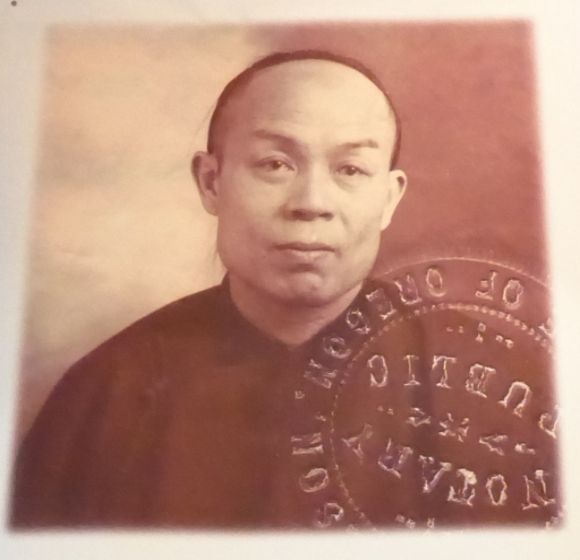

The National Archives and Records Administration in Seattle now preserves the documents written by the “Chinese inspectors.” In these archives, there are about 80 individual Chinese who called The Dalles home. According to the Museum display:

“These documents, produced by a government hostile to their presence in this country, are perhaps the best foundation we have to help rebuild the story of Chinatown and the people who lived there, they have finally given us the gift of names and faces to the otherwise forgotten Chinese residents of The Dalles.”

Among the anti-Chinese laws:

- 1857: Oregon required Chinese miners to pay a tax of $2 per month

- 1862: Oregon required all persons of Chinese ancestry to pay a $5 per year tax for residing in Oregon

- 1866: Oregan banned interracial marriage (not repealed until 1951)

- 1870: U.S. deny Chinese the right to naturalization

- 1882: Chinese Exclusion Act denies entrance to, or travel in and out of the U.S., by men of Chinese ancestry, with the exception of merchants, teachers, students, and diplomats

- 1885: The City of The Dalles banned the practice of carrying laundry baskets that hung from a pole resting over one’s shoulders

- 1889: In U.S. v. Wong Kim Ark, the Supreme Court granted Wong Kim Ark, an American born Chinese, citizenship

- 1917: the U.S. Immigration Act banned immigrants of Asian ancestry

- 1924: U.S. establishes national origin quotas and bans anyone not eligible to become an American citizen (Chinese and Japanese could not become citizens)

- 1943: the Chinese Exclusion Act was repealed and limited Chinese immigration was allowed

According to the Museum display:

“Their appearance, their style of dress, their pigtails and their language set the Chinese apart from the predominantly European American population in The Dalles. Their foreign ways were often disparaged, mocked and misunderstood, and were the basis for discrimination. The Chinese brought their culture to their new community through the items sold in their stores, the meals cooked and served in their restaurants, and with their celebrations and funerals.”

A strong Anti-Chinese Movement began in the western states in the 1870s. Chinese immigration had begun at a time when employment was on the rise. With the recessions of the 1870s and 1880s, many Americans blamed the Chinese for the lack of jobs. In addition, cultural differences fueled anti-Chinese prejudice. According to the Museum display:

“Many Americans felt that Asian cultures could never assimilate to the ‘American Way of Life’ and many thought the Chinese were ‘inferior’ to whites.”

The Dalles Chinatown faded away. According to the Museum display:

“Single Chinese men had few opportunities to marry and start a family. Some never intended to stay long, only long enough to earn enough, and then return home. With only a few children born into the community, and a declining need for their goods and services, there were few incentives to remain. The nearby much larger Chinatown of Portland beckoned.”

Shown above are some of the archaeological findings from the Chinatown site.

Shown above are some of the archaeological findings from the Chinatown site.

More archaeological findings.

More archaeological findings.

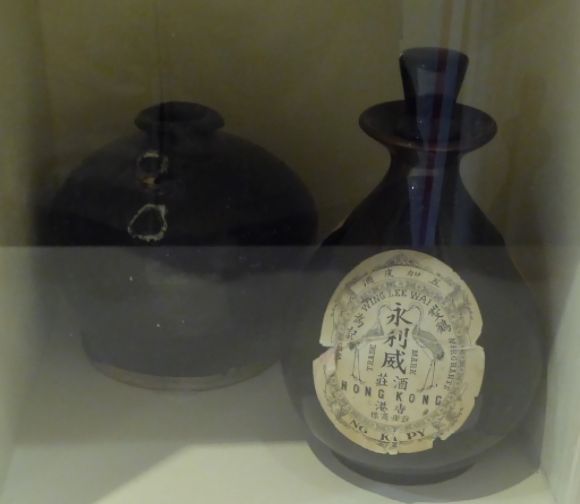

Some of the bottles uncovered in the archaeological dig.

Some of the bottles uncovered in the archaeological dig.

Both Chinese and European ceramics were uncovered.

Both Chinese and European ceramics were uncovered.

The coin sword shown above was found within a wall in a house. Coin swords were used for good luck and to ward off evil influences.

The coin sword shown above was found within a wall in a house. Coin swords were used for good luck and to ward off evil influences.