What You Should Know About California And Forest Fires

This situation sucks. It really, really sucks. The death toll and damage are horrific, and when the ash settles, tens of thousands of lives will never be the same. As is the norm with these tragedies, the lion’s share of pain will be borne disproportionately by those least equipped to sustain it: the elderly, the young, and the underprivileged.

As I’m writing this, the deadliest, most destructive fire in California’s History is incinerating swaths of our largest state. Over eighty people are confirmed dead, over a thousand are unaccounted for, and nearly eighty-thousand have been evacuated and may have no home to return to. The two attached graphs demonstrate just how out of the ordinary this current disaster is.

Source: The 2018 “Camp Fire” is already the most destructive fire in history — and it’s still burning.

Source: The 2018 “Camp Fire” is already the most destructive fire in history — and it’s still burning.

Even in the areas unaffected by flames, smoke is polluting the air, turning the simple act of breathing into a dangerous habit — especially for the immunocompromised. Smoke masks have been sold out for days and there are now efforts to fund shipping to send more masks into the area.

Like I said, the situation really, really sucks. So please do not mistake my casual writing tone for one that does not recognize the gravity of the horror. And please forgive me if it seems that my decision to write on this topic through a political lens is imprudent. My aim is not to “politicize” this tragedy, rather it is to note that this tragedy is to a degree political to begin with, and preventing it in the future requires political solutions. As grim as it is to say, we now have an opportunity to learn lessons, and if we don’t learn now, then we are simply asking to suffer and re-suffer this destruction for the years to come.

I’ve divided this piece into six main sections, each viewing the problem and solutions from a different angle.

-

The section where Smokey Bear is wrong.

-

The necessary section about climate change and fires.

-

The obligatory section about President Trump.

-

The section about fixing all the problems.

-

The section where I tell you what you should remember.

THE SECTION WHERE SMOKEY BEAR IS WRONG

And yes, it’s “Smokey Bear,” not “Smokey The Bear.” But whatever you call him, he was wrong — or at least unhelpful.

Smokey Bear was the furry spokesbear for a cultural movement that, while well-intended, eventually inadvertently led to the destruction of homes and human life.

In the early 1900s, after the establishment of the U.S. Forest Service, the government placed swaths of land under governmental protection. In this era, “protection” meant preventing the area from being consumed by fire — an instinctively logical standpoint. As a result of this, throughout the early-mid 1900s, anti-wildfire campaigns sprung up to alert the public to the dangers of wildfire, Smokey Bear being one of them. These campaigns were a combined force of government agencies interested in “preservation” and private interests such as recreational groups and the timber industry who knew that a lush forest was more marketable and profitable to customers than a flaming pile of ash. These anti-wildfire campaigns were so effective that some of their slogans and imagery are still around today, for better or worse.

It wasn’t until the mid-late 1900s that we began to realize what Native Americans had known long before us: Fire suppression doesn’t work. In fact, the very steps we were taking to protect our forests and the property surrounding them were the same steps that led to their destruction. This effect is known as the “Smokey Bear Effect.”

Fire suppression fails for one simple reason: Fires are supposed to happen. Fires reset the cycle of a wildland and they keep ecosystems in check. But in a fire suppressed forest, this reset doesn’t occur. So, as forests mature uninhibited and more and more carbon is converted into wood, the pot of fuel that a flame may access becomes larger and larger. Then, when a fire is finally lit, it burns hotter and longer than it may have otherwise.

And while fire suppression isn’t the only cause, statistics do show that fires have gotten bigger in recent years. Especially recently. Last year (2017) was the most destructive year on record for wildfires in California — that is, until this year was correctly predicted to be even worse (Source, Source). And though 2018’s fire season is still raging and the damage is not yet fully assessed, California is currently experiencing its deadliest wildfire on record (Source). The graph below from a California EPA report demonstrates that while small fires have remained relatively constant and predictable since the 1950s, large fires have worsened dramatically.

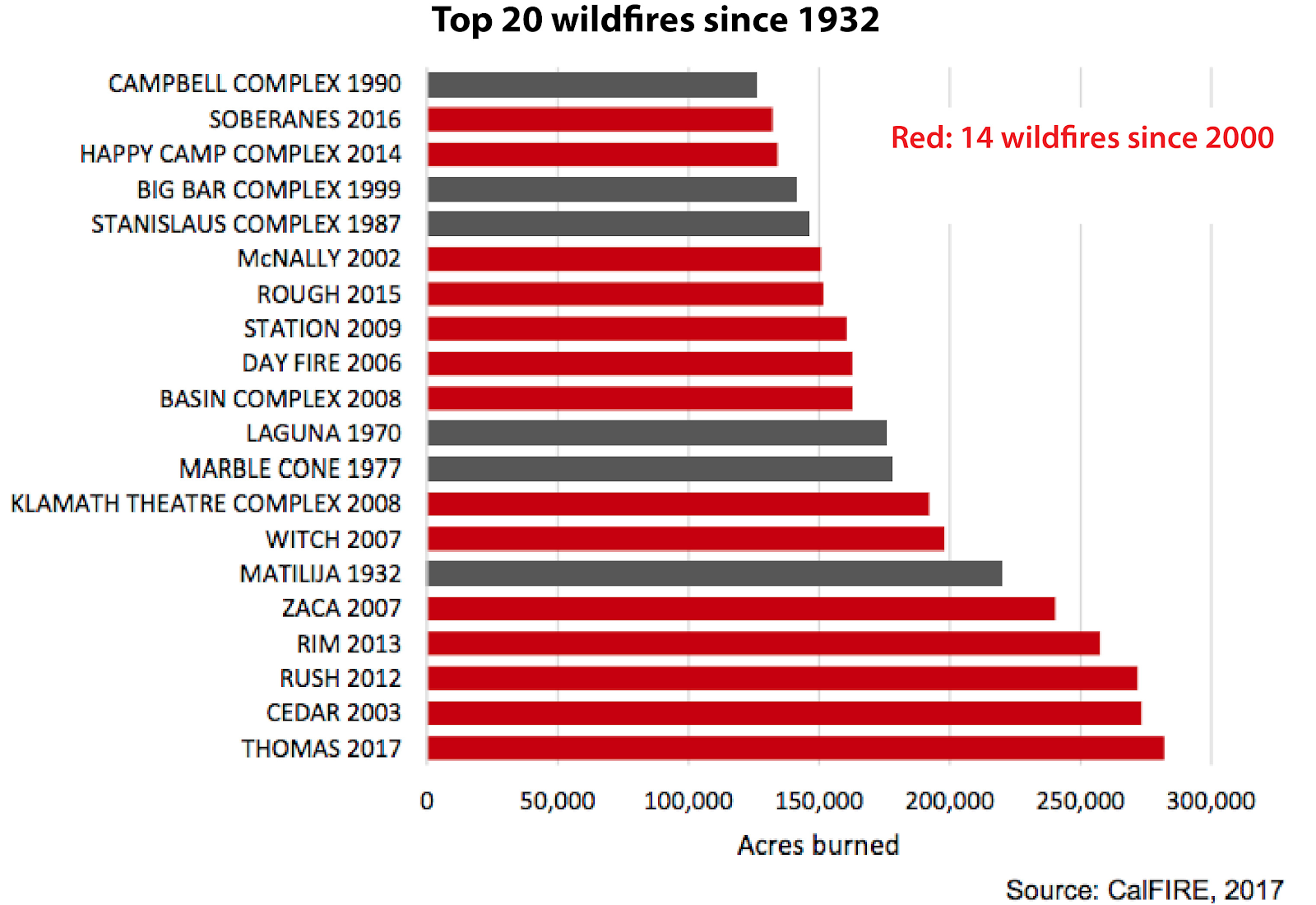

And as the below chart below shows, out of the top 20 wildfires from 1932-2017, 14 have happened since 2000. This chart will become even more startling once 2018’s Camp Fire and possibly Woolsey Fire are added. Camp Fire is currently 80% contained and has burned over 150,000 acres.

Granted, the most recent worsenings may also be due in large part to climate change, which will be discussed shortly, but historically improper forest management and a hard-to-expunge anti-fire sentiment in the agencies and interests who manage forests have certainly contributed.

To understand the problem with fire suppression comprehensively, though, we must also understand some ecological principles.

Fire suppression is bad ecologically because nature actually needs fires. For instance, jack pines and giant sequoias both carry their seeds in cones that only open up and release the seeds when exposed to a fire’s heat. The trees evolved this way because the fire heat acts as an indicator to trees that there is likely to be low competition from underbrush and a sapling may thrive in the post-fire environment. Sequoias also rely on fires to reduce the growth of smaller tree species that would otherwise out-compete them. These competitors are species such as white fir or incense cedar, which are both able to survive in the shade of a thick forest.

Fire is also beneficial in culling invasive species that are well-adapted to the environmental conditions otherwise, but are incapable of rebounding after a fire. As noted above, fire is essential in “resetting” an ecosystem in a number of ways. For one example, wood ash is a stellar natural fertilizer and it can act as a liming agent that improves regrowth of small plants. Compounding this effect, fire removes the upper leave canopy which permits rain and sunshine to reach the forest floor, further providing nourishment to the plants on the forest floor.

These benefits, among others, make fire not just helpful, but essential to ecosystems.

However, for all that Smokey Bear got wrong, he got one thing right: humans are the main cause of forest fires. Only about 10% of wildfires originate from natural causes. The other 90% of fires are caused by sparks from electrical equipment, improperly extinguished cigarettes, unattended campfires, arson, or any of the other fire-genic activities humans partake in (Source). For an example, the currently burning Camp Fire is most likely traceable back to a power line problem from PG&E (Source).

Forest management is undoubtedly a factor in forest fires. However, as mentioned previously, it is only one facet of the problem. Climate change plays an increasingly starring role in our natural disasters.

THE NECESSARY SECTION ABOUT CLIMATE CHANGE

Climate change is hitting California hard. Recent droughts, while not entirely attributable to climate change, have left landscapes parched, and the dryness can turn a previously lush forest into a landscape of mega-matchsticks. Attached is a graphic from a California EPA Report on the severity of droughts going back to 1985.

Data also shows that the annual average temperature of California is rising. This raises concerns for drought because with every 1.8 degrees Fahrenheit that the average air temperature rises, 15% more rain is required to rehydrate plants (Source: fire scientist Mike Flanigan to AP). Without this extra water, the dryness creates a habitat suited perfectly for a wildfire.

The higher temperatures, combined with unpredictable weather, changing wind patterns, and altered snow melt can lead to a more dangerous, volatile environment in which fires can thrive.

THE OBLIGATORY SECTION ABOUT PRESIDENT TRUMP

As I transition to discussing responses, I’ll begin with the absolute worst one, provided free of charge by our nation’s leader.

There is no reason for these massive, deadly and costly forest fires in California except that forest management is so poor. Billions of dollars are given each year, with so many lives lost, all because of gross mismanagement of the forests. Remedy now, or no more Fed payments! (Source)

While Mr. Trump retreated from this statement in later tweets, but he eventually doubled down on the sentiment that inept Californian land management was to blame and that climate change played no part (Source). He even reiterated his conspiracy theory that climate change is an insignificant, invented threat (Source).

In response to Mr. Trump, Harold Schaitberger, the President of the International Association of Fire Fighters, composed a statement saying:

"The early moments of fires such as these are a critical time, when lives are lost, entire communities are wiped off the map and our members are injured or killed trying to stop these monstrous wildfires. To minimize the crucial, life-saving work being done and to make crass suggestions such as cutting off funding during a time of crisis shows a troubling lack of real comprehension about the disaster at hand and the dangerous job our fire fighters do. His comments are reckless and insulting to the fire fighters and people being affected." (Source)

Fire fighters weren’t having it from Trump — and with good reason. Mr. Trump wasn’t useful in providing facts, he wasn’t useful in providing empathy, and he wasn’t useful in generating fruitful debate. But within Mr. Trump’s tweet, there is one small sliver of ignorance that is worth dissection, and I will point it out. So for now, as difficult as it is to put aside the gross indelicacy with which he addressed the heartbreaking loss of life, we must do our best and focus on this one idea.

Here, I wish to focus on Mr. Trump’s claim that poor modern day Californian land management is to blame for the disaster currently on display.

To begin, we must note that bashing Californian politics is a favorite pastime of right-wing pundits and politicians. Aside from the run-of-the-mill “out-of-touch coastal elite” slurs that grace the lexicon of the right-wing punditry, provocateurs also bemoan the state’s policies on sanctuary cities (Example) and income taxes (Example). Furthermore, President Trump has habitually picked personal fights with Democratic Governor Jerry Brown (Example) and former Republican Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger (Example). To understand the motivations behind President Trump’s statements, we must keep these grudges in mind.

But now, let’s return to the facts behind the idea that California is to blame for its mismanagement of its environment.

The truth is, 57% of California’s forestland is federally owned and managed. This means that the management of these forests is under federal agencies such as the U.S. Forest Service and the Department of the Interior, both of which work under President-appointed leadership. Of the other 43% of forestland, 40% is privately owned by interests such as timber companies or Native American tribes. The final 3% is either state or local agency owned. So, quite frankly, California’s state government actually does extremely little forest management. Instead, the majority of government-managed forest is under the executive agencies of the USFS and the DOI, each of which have been subject to President Trump’s policy wishes.

President Trump has consistently proposed budgets that would slash the ability of the USFS and DOI to function as they desire. For instance, in his proposed 2019 budget, he requested a 19% reduction in the USFS research budget, along with a proposed 8% cut in the research budget National Parks Service and a 26% cut to the research budget of the U.S. Geological Survey (Source). Each of these agencies is tasked to some degree with learning about wildfires and proper land management, and when their budgets are cut, their efforts are weakened. While the President did propose a small budget boost toward reducing fire risk, many interest groups pointed out that he did not go nearly far enough. The below is a February, 2018 response from “American Forests,” a group dedicated to forest conservation (Source).

“While the Administration’s budget proposes a slight increase in funds to reduce wildfire risk on America’s national forests, it does not propose a comprehensive fix to the wildfire suppression budgeting issue, especially regarding the erosion of the U.S. Forest Service’s budget due to the rising costs of suppression. The budget ultimately reduces overall funding for the National Forest System by more than $170 million. Of equal concern, the budget proposes to eliminate key programs from the State and Private Cooperative Forestry division including Urban and Community Forestry, Forest Legacy, Community Forests and Open Space, and Landscape Scale Restoration.

“The proposed reductions to the national forests and to state and private forestry also come at a time when U.S. forests are needed to help slow climate change, yet also face existential threats from a changing climate. America’s forests and forest products currently sequester and store more than 14 percent of annual U.S. carbon emissions, a natural climate solution that requires continued investment in keeping forests as forests, and managing for healthy forests in a changing climate.”

So, while Mr. Trump may point fingers of blame at others for what he considers poor land management, the buck, or at least a good portion of the buck, actually stopped with him.

But as the Associated Press pointed out, land management is actually likely not the biggest contributor to the severity of recent fires (Source). Instead, scientists from all across the world said that, in fact, climate change and poor luck are perhaps larger factors. The first nine months of 2018 were the fourth-warmest on record for California, and the summer was the hottest on record. Add to this the previous years of drought and the result is swaths of shriveled shrubs and bone-dry trees for tinder and fuel respectively.

In conclusion to this obligatory section about President Trump, our President is wrong. Very wrong. He tried to talk about something he knew little about, and when interest groups saw the absolute ignorance he was spreading, they spoke up. While poor forest management may have played a role in the rampant fires we see now, it was not a prominent one, and the fault for the poor management actually likely falls on the United States Executive Branch or private industry — not California.

THE SECTION ABOUT FIXING THE PROBLEMS

So, we understand the problem — or at least we understand how complex the problem is. So what are some solutions?

Well, there are a lot of half-solutions. The first thing we must understand is that fire fighting isn’t simply about having more water to douse the fire with. Instead, the best tactic is to cut off access to fuel so that the fire burns itself out. The red-dyed retardant that can often be seen dropping from aircraft does not serve to extinguish the fire, it serves to stop or slow it by reducing the effectiveness of the fuel it covers.

Source

Source

When it comes to making forest fires less destructive, it’s really about keeping fuel quantity under control through smart land management. Fortunately, California has a forward-looking citizenry and legislature that is fully aware of the impending risks that climate change and forest fires expose them to, and a number of reports and recommendations have surfaced to advise policy. The two reports I’ll discuss here are from the California EPA and a watchdog group called the Little Hoover Commission (EPA Report, LHC Report).

The Little Hoover Commission Chair, Pedro Nava, wrote the following in a letter to ranking members of the California Legislature.

“Proacti�ve forest management prac�tices recommended by the Commission gradually will rebuild healthy high-country forests that store more water, resist new insect infesta�tions and check the speed and intensity of wildfires. Inves�ting upfront to create these healthier forests will pay dividends in the long run by curbing the spiraling costs of state firefighting and tree removal while building stronger recreati�on and sport economies in the Sierra Nevada. Forests largely restored to the less crowded natural conditi�ons of centuries ago — through greater use of prescribed burning to replace unilateral policies of fire suppression and mechanical thinning to remove buildup of forest fuels — also will improve wildlife habitat, enhance environmental quality and add to the resilience of mountain landscapes amidst the uncertain�es of climate change.”

In this paragraph, the Chair sets forth a backdrop for what he believes a good solution should accomplish. The report believed that good fire policy isn’t about being anti-fire, it’s about being pro-ecosystems. Good fire policy sees fire as an asset — a tricky asset, but an asset nonetheless.

In regards to specific recommendations, the EPA and the LHC encouraged the California and Federal Governments to adopt the following.

More prescribed burns.

Prescribed burns reduce the amount of fuel available for a fire, thereby weakening it or slowing it — if not entirely preventing it. Prescribed burning has benefits that simple forest clearing does not, as the ecological effects of fire are unique and essential to landscapes.

More accommodating prescribed burn regulations.

California has relatively strict air quality standards which stem from their environmentally conscious legislature. While these standards are in many instances beneficial to the state’s environment, they can create a hindrance to planning and carrying out organized burns. These regulations should be relaxed to allow for better burn planning. Additionally, technology and ecosystem modeling should be used to determine when and where prescribed burns may be used such that air quality will be least adversely affected.

Better interagency communication.

Interagency communication has been the bane of good environmental policy since, well, since there were multiple agencies that needed to communicate. Managers of Californian wildlands are not exempt from the plague.

As noted previously, the majority of California’s forestland is owned federally by the DOI, the USFS, or private interests. These different agencies inevitably have different goals and beliefs of what “good management” looks like. For instance, the USFS, in recognizing the need for natural fire, may permit a wildfire to burn uninhibited throughout a landscape. However, a neighboring timber company may not be so keen to have an unpredictable, profit-destroying force just next door. One step to reducing this interagency conflict is to include more stakeholders in policy meetings and to be sure that communication is always open and honest so that burns and harvests can be coordinated to best reduce the risk of destructive fires.

Expanding the timber and biomass markets.

This answer is the traditionally conservative one and it attempts to harness the power of the private sector to solve a public problem. The solution is valid, but imperfect.

Proponents of this solution argue that if timber and biomass companies are granted greater latitude in their deforestation activities they will both reduce the presence of fire-fuel that has amassed over the years and will do so at no cost to the taxpayer. Though the argument has merit, there are two concerns.

The first is that deforested land becomes highly vulnerable to a non-native species called “cheatgrass,” which is highly flammable and is known to be a good starting tinder for wildfires. The second concern is that many of California’s forests are too dry for use in timber, and the only real market use for the wood is as biomass for producing energy. Unfortunately, Californian biomass facilities have been closing down. To promote more biomass energy production to incentivize dry-wood harvest, California should consider subsidizing the facilities or examining whether they can be retrofitted with greener technology so they will qualify for tax incentives.

If the problems stated above can be navigated, the result would be a partial market solution to the problem of forest fires.

Educate Californians — both officials and citizens.

Currently, some Californian environmental groups outright oppose prescribed fire and logging on principle, which makes forward political movement on forest management difficult. By better educating Californians about the environmental and public health benefits of prescribed burns and smart timber harvest, citizen pressure will shift to account for a more comprehensive view of forest policy. Additionally, legislators themselves, both state and federal, must be educated on what makes good wildland policy. Through the provision of information, we can address the problem of forest fires with the complexity that it deserves.

Governor Jerry Brown and the California Legislature have already taken action on some of these suggestions, though whether they have gone far enough is unclear. In 2016, Governor Brown signed SB 859 which acted to expand the use of dried trees for biomass, thereby increasing the market for wood harvest. And in May of 2018, following the California EPA’s report on climate change, Governor Brown signed an executive order to double the amount of land that would be “actively managed” through thinning and prescribed burns. These orders also increased education and outreach to landowners regarding fire prevention on their lands and it implemented training and certification programs that would provide better staffing for performing prescribed burns. Furthermore, in September 2018, Governor Brown signed SB 901, which, among other fire prevention provisions, provided small-landowner incentives to remove dead trees from their land and offered utilities an easier pathway to recoup their losses after a fire — though the latter provision was somewhat controversial.

Suffice it to say that California is certainly aware of the danger that fires pose to their safety. The state has done what they can, though they are seeing now that it wasn’t enough.

The question remains, however, whether it is even possible to “do enough.”

THE SECTION WHERE I TELL YOU WHAT YOU SHOULD REMEMBER

The history of forest fire management is a storied one, and the current state of our land management cannot be understood without the historical context. But equally important to the historical view is the future view. As climate change continues contributing to mass disasters across the world, the human race will have the reality of the threat shoved in our faces in increasingly gruesome, horrific manners.

The death and destruction wrought by this year’s fires is not entirely due to climate change, but the evidence that it played at least some significant role is undeniable. In noting this, I feel obligated to mention that the losses of life we California has experienced are far from the first casualties of climate change. Poorer, less privileged nations across the globe have already been suffering from this crisis for decades, experiencing increasingly volatile weather, more prevalent sickness, and longer droughts.

Now the deaths have reached our shores. And while we can’t ever repent for the suffering the developed world’s pollution has imposed on those less fortunate, we now have a chance to see the suffering up close and realize that the time to mitigate climate change is now.

Part of this mitigation, undoubtedly, requires acknowledging that the brash brand of “leadership” our current president embodies is unhelpful to progress. The smoke screens of blame and misdirection that our President erects compromise our nation’s responses to the deadly threats and cause real damage to communities.

Our responses to these threats cannot be simple. No sound bite can encapsulate what really needs to be done. And while intelligent solutions do exist, their potential to be implemented effectively will likely be limited by the ever-elusive taxpayer dollar. Good solutions need evidence, facts, and creativity, but they also need to be attractively marketable to politicians and the American public.

To close this essay, I must caution that this problem will not be resolved quickly. Climate change is worsening and the fire threat will worsen accordingly. Decades of forest mismanagement cannot be reversed in a matter of a few years. We need patience.

In the years to come, as we will again be forced to watch helplessly as fire yet again consumes our landscapes and towns, frustration, anger, and blame will be tempting. These feelings are instinctive. They may feel rational. When we see destruction, our instinct is to look for justice. But we have to remind ourselves of the historical hugeness of this problem and that it cannot be blamed on any single person or single group — perhaps not even on any single ideology.

Our steady tread toward solutions must be clear-headed and cooperative. It must be intelligent and it must be unified. In the face of forest fires and climate change, our entire human race is in encountering a lethal, horrific force, the severity of which is the result of our own short-sighted greed.

There are going to be more fires, there are going to be more deaths, there is going to be more destruction. But we have some ideas for solutions. Now, we have to use them.

-Ben Chapman