Archaeologists use the term Mesoamerica in referring to Mexico and the adjacent areas of Central America which were the home to Native American civilizations prior to the Spanish invasion. The Formative Period in Mesoamerica is an era of spectacular social transformation marked by the development of social stratification and monument building.

With regard to dating, the Formative Period is generally seen as beginning about 2000 BCE and lasting until about 200 CE. Archaeologists often divide the Formative Period into Early (2000 BCE to 900 BCE), Middle (900 BCE to 500 BCE), and Late (500 BCE to about 200 CE). It should be noted that some researchers feel that the period begins somewhat later (1500 BCE) and ends somewhat later (250-290 CE).

During the Early Formative there is increasing social stratification (social ranking) which is indicated by elaborate household structures in some areas. Construction of ritual architecture—temples and pyramids—begins in a number of sites. There are also motifs which represent some of the supernatural entities which are important in cosmological beliefs. These motifs are seen on pottery vessels, pottery figurines, and stone carvings.

During the Middle Formative there appears to be a population increase with settlements becoming larger and more abundant. During this time, some of the monumental architecture was placed around a rectangular plaza. With regard to social stratification, D. C. Grove, in an entry on this period in The Oxford Companion to Archaeology, reports:

“Exotic objects found in some of the Middle Formative Period graves provide evidence of an emerging elite who marked their special social rank with jade ear ornaments and jewelry, and iron ore mirrors.”

The transition from the Middle Formative Period to the Late Formative Period is marked by the appearance of large population centers, such as Monte Albán and Cuicuillco. The intensification of agriculture includes the use of irrigation systems. D. C. Grove writes:

“With nucleation and intensive agriculture, Mesoamerica began its urban revolution. Writing and calendrical systems, often considered by archaeologists to be characteristics of civilization, appeared for the first time on Late Formative monuments and inscriptions in several regions of southern Mesoamerica.”

The figures shown above are from Zacatecas. These are on display in the San Bernardino County Museum in Redlands, California.

The figures shown above are from Zacatecas. These are on display in the San Bernardino County Museum in Redlands, California.

The pottery from Central Mexico is shown above. These are on display in the San Bernardino County Museum in Redlands, California.

The pottery from Central Mexico is shown above. These are on display in the San Bernardino County Museum in Redlands, California.

This ceramic figure from Nayarit dates to the Late Formative Period. Notice the interesting nose piece. This piece is on display in the Portland Art Museum.

This ceramic figure from Nayarit dates to the Late Formative Period. Notice the interesting nose piece. This piece is on display in the Portland Art Museum.

This ceramic piece is from Nayarit. Notice the large nose pieces on the figures. With the drummer seated in the middle, the dancers appear to be engaged in a circle dance. This piece is on display in the Portland Art Museum.

This ceramic piece is from Nayarit. Notice the large nose pieces on the figures. With the drummer seated in the middle, the dancers appear to be engaged in a circle dance. This piece is on display in the Portland Art Museum.

The Chupicuaro pieces from Guanajuato are shown above. These are on display in the San Bernardino County Museum in Redlands, California.

The Chupicuaro pieces from Guanajuato are shown above. These are on display in the San Bernardino County Museum in Redlands, California.

Chupícuaro is the burial ground for a village in the state of Guanajuato, about 80 miles northwest of the Valley of Mexico. Archaeologists uncovered the skeletons of 390 individuals who had been buried in simple graves with abundant offerings of pottery, figurines, jade, and clay objects. In their book Mexico: From the Olmecs to the Aztecs, Michael Coe and Rex Koontz report:

“The pottery vessels found in the cemetery are in both shape and decoration quite exuberant.”

This ceramic figure from Chupicuaro is on display in the Portland Art Museum.

This ceramic figure from Chupicuaro is on display in the Portland Art Museum.

The ancient people of Mexico had two domesticated animals: the dog and the turkey. Dogs seem to have had special mortuary significance. This ceramic figure from Colima is on display in the Portland Art Museum.

The ancient people of Mexico had two domesticated animals: the dog and the turkey. Dogs seem to have had special mortuary significance. This ceramic figure from Colima is on display in the Portland Art Museum.

The tropical Gulf coast of southern Mexico was dominated during the Early and Middle Formative Periods by an archaeological culture called Olmec. D. C. Grove writes:

“The Olmec stand out as the first society in Mesoamerica to create stone monuments, and these impressive creations are the distinguishing trait setting the Olmec apart from other Mesoamerican societies at that time.”

The designation Olmec is from Olmeca meaning “rubber people.” One of my archaeology professors, Wigberto Jimenez Moreno, preferred to call them Tenocelome, meaning “jaguar people” in reference to the jaguar theme in much of their art. We don’t know what they called themselves or what language they spoke.

The Olmec art style seems to reflect their religion. In their book Mexico: From the Olmecs to the Aztecs, Michael Coe and Rex Koontz write:

“The hallmark of Olmec civilization is the art style. Its most unusual aspect is the iconography on which it is based, through which we glimpse a religion of the strangest sort. The Olmecs may have believed that at some distant time in the past, a woman had cohabited with a jaguar, this union giving rise to a race of were-jaguars, combining the lineaments of felines and men.”

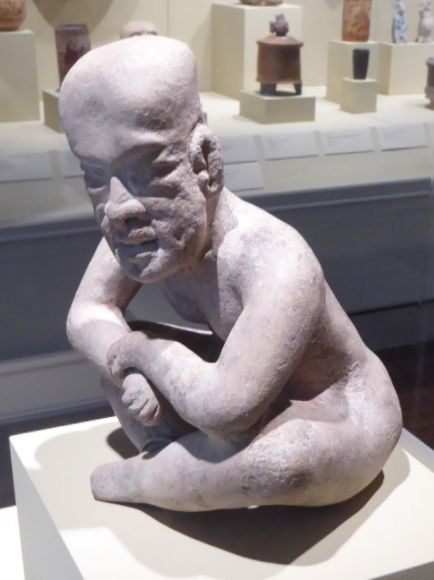

In Olmec art, were-jaguars are often depicted as small, fat babies with snarling mouths. Sometimes they are shown with fangs and even claws. The heads are cleft at the top.

The early archaeologists who worked on the Olmec sites viewed them as more advanced than other Mesoamerican sites at that time and so it seemed logical to view Olmec as Mexico’s mother culture. Michael Coe and Rex Koontz report:

“There is now little doubt that all later civilizations in Mesoamerica, whether Mexican or Maya, ultimately rest on an Olmec base.”

In their Encyclopedia of Ancient Mesoamerica, Margaret Bunson and Stephen Bunson report:

“As the Olmec prospered and began to set their own artistic and cultural goals, the products of their various industries began to appear in the marketplaces of other cultures.”

As the archaeological understanding of non-Olmec sites during the Formative Period has increased, some archaeologists now view Olmec as having a distinctive art style which diffused widely throughout the region rather than as the mother culture of the region. D. C. Grove writes:

“During the Early and Middle Formative Period many regions of Mesoamerica manifested important developments in architecture and social complexity that were apparently endemic to them. In studying the Formative Period it would be a mistake to ignore those regional developments, or to attribute them to Olmec influences that are unproven at this time.”

Shown above is a ceramic Olmec ceramic figure on display in the Portland Art Museum. Notice the cranial deformation which results in the high forehead. The infant’s head is bound, which results in this deformation. This is an indication of high status.

Shown above is a ceramic Olmec ceramic figure on display in the Portland Art Museum. Notice the cranial deformation which results in the high forehead. The infant’s head is bound, which results in this deformation. This is an indication of high status.

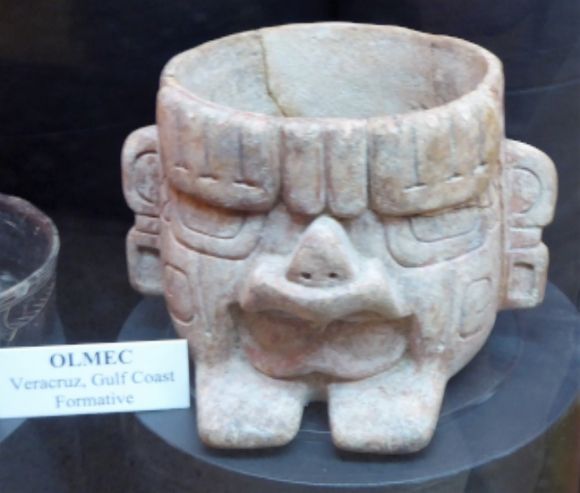

This Olmec bowl is on display in the San Bernardino County Museum in Redlands, California.

This Olmec bowl is on display in the San Bernardino County Museum in Redlands, California.

These Olmec artifacts are on display in the San Bernardino County Museum in Redlands, California.

These Olmec artifacts are on display in the San Bernardino County Museum in Redlands, California.

Ancient Mesoamerica

More about Ancient Mesoamerica:

Ancient Mexico: The Zapotec and Monte Alban

Ancient America: Some Artifacts from Teotihuacan

Ancient America: Some Maya Artifacts (Photo Diary)

Ancient America: Tlatilco, an Ancient Site in the Valley of Mexico

Ancient America: Artifacts from Western Mexico (Photo Diary)