In Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and Montana during the nineteenth century, American settlers formed militia groups for the purpose of killing Indians. While supposedly formed for the purpose of “defense”, the militias were often fueled by a genocidal bloodlust which was satiated by murdering Indians and mutilating their dead bodies to obtain “trophies” in the form of body parts—ears, heads, hands, genitals—which were proudly displayed when they returned to their communities. While the Indians were accused of many crimes, many of which were imaginary, the militias had no concern for justice, for finding the people who had actually committed the crimes and bringing them to an actual trial in an actual court of law. For the militias, all Indians were the same so they killed Indians regardless of age—ranging from infants to elders—and without regard to gender.

In 1855, war broke out between the Indians of the Columbia Plateau and the American settlers who were invading the region. The Oregon Volunteers, frustrated by their inability to locate Yakama leader Kamiakin, whom they blamed for the war, turned their attention to the friendly Walla Walla and their leader Peopeo Moxmox.

At the Touchet River, the Oregon Volunteers encountered Peopeo Moxmox with a group of about 60 Walla Walla and Palouse warriors. Peopeo Moxmox and three other chiefs approached the Americans under a white flag of truce. Peopeo Moxmox asked the Americans why they were there and was told that the Army was there to punish him and his people. Peopeo Moxmox denied committing any crimes. The Army then violated the flag of truce and held Peopeo Moxmox and his companions as hostages.

The capture of Peopeo Moxmox angered many Indians. The army marched on the peaceful Walla Walla and Palouse village, but found it deserted. When a general battle with the Indians started, Peopeo Moxmox was murdered and his body mutilated.

One of the Oregon volunteers reported that there had been an attempt to escape on the part of the captive Indians. He described the scene:

“It was all over in a minute, and three of the five prisoners were dead; another was wounded, knocked senseless and supposed to be dead, who afterward recovered consciousness, and was shot to put him out of his misery, while the fifth was spared because he was a Nez Perce.”

In another report, Peopeo Moxmox was knocked to the ground and the volunteers fired their weapons point blank into his body.

In their book Renegade Tribe: The Palouse Indians and the Invasion of the Inland Pacific Northwest, Clifford Trafzer and Richard Scheuerman write:

“The volunteers murdered Peopeo Moxmox but defended their actions as justifiable because they felt that the chief was stalling for time to allow the Indians to mobilize their forces. Besides, the soldiers maintained that if released, the chief would rise up against the Americans.”

Background: The Americans

In 1848, Oregon Territory had been established to provide a more formal political structure with which to deal with the Indian nations and the fears of American settlers regarding potential Indian attacks. Two years later, Congress passed the Oregon Donation Land Law which granted non-Indians the right to occupy lands in the territory regardless of the Indians who might be living there. The tribes did not receive compensation for the land which was taken from them and given to the American settlers.

The American right to simply take land away from the Indians was inspired in part by the philosophy of Manifest Destiny—that America was destined (possibly by God) to expand from ocean to ocean—and by the legal notion of the Discovery Doctrine—Christian nations have the right, if not the obligation, to rule over all non-Christian nations. Americans ignorantly assumed that Indians had no concept of land ownership and that Indians did not develop the land, that the land was free for the taking.

Americans viewed, and many still view, Indians through the lens of racism which sees Indians as innately inferior, perhaps even subhuman, and thus killing an Indian is of little religious or civil consequence. Historian Francis Haines, in an essay in Idaho Yesterdays, writes:

“Many of the settlers were professed Christians. They needed some sort of rationalization to justify their extermination of the natives and the seizing of their land. Hence their insistence that the Indian was really a predatory wild animal, and that his extermination was both justified and desirable.”

American Army officers who had been trained at West Point were required to take a course in Christian ethics which used Emer de Vattel’s 1758 text: The Law of Nations, or, the Principles of the Law of Nature Applied to the Conduct and Affairs of Nations and Sovereigns. According to this book:

“When we are at war with a savage nation, who observe no rules, and never give quarter, we may punish them in the persons of any of their people whom we take (these belonging to the guilty), and endeavor, by this rigorous proceeding, to force them to respect the laws of humanity.”

Executing a prisoner was an acceptable action if the prisoner was a member of a ‘savage nation.’ There was also an assumption that Indian nations were “savage” nations, without law, morals, or rules.

Background: PeoPeo MoxMox

Like many other Indian leaders in the Columbia Plateau area in the first half of the nineteenth century, Walla Walla chief Peopeo Moxmox saw some advantages in having a son who would be familiar with American culture and who spoke English. Thus, in 1836, he enrolled his son To-ayah-nu at the Willamette Mission School in Oregon. The missionaries, in their zeal to strip all vestiges of Indian culture from their students, gave To-ayah-nu the English name Elijah Hedding after the Bishop of the Methodist Episcopal Church. After six years in the mission school, Elijah Hedding, as he was now known, returned home to the Walla Walla.

In 1842, the United States appointed Elijah White as the Indian agent for the Oregon Territory which was jointly claimed by both Great Britain and the United States. White is generally described by historians as “a scheming man,” “contentious,” and “somewhat of a flimflammer.” He was unconcerned that Indian nations were sovereign entities and sought to impose American concepts on them, including Christianity and the rule of a single, autocratic chief.

In 1843, White called called a council of the Nez Perce, Cayuse, and Walla Walla. At the council, White attempted to impose on the Indians a set of “laws.” Walla Walla chief Peopeo Moxmox asked White:

“Where are these laws from? Are they from God or from the earth? I would that you might say they were from God. But I think that they are from the earth, because, from what I know of white men, they did not honor these laws.”

In 1844, Elijah Hedding joined a group of about 50 Walla Walla, Spokan, Cayuse, and Nez Perce who traveled to California to buy cattle. In California, they traded horses and furs for the cattle. Before returning north, they stopped to hunt in the mountains where they became involved in a fight with a band of California Indians. As a result of this conflict, they acquired 22 horses and mules. American settlers in the area then claimed that the horses and mules had been stolen from them and demanded their return. The Indians refused. In the ensuing conflict one chief – Elijah Hedding – was killed and the Indians fled without their cattle.

By the time the band returned home, anti-American sentiments were running high. Some warriors suggested exterminating the Americans in Sacramento, while others suggested that the Americans in the Willamette area of Oregon also be wiped out. Peopeo Moxmox, however, eventually convinced them that war against the Americans would be a disaster. He brought up the fact that the laws which Elijah White had attempted to impose upon them provided for the punishment of American offenders.

The Nez Perce leader Ellis talked with the Indian agent and demanded punishment for those who killed Elijah Hedding. The agent, knowing that hanging the American would be impossible, stalled the Indians and promised them money for cattle.

At this time, it would seem that Peopeo Moxmox had adequate reason to dislike and distrust the Americans. However, he continued to advocate peace between his people and the American settlers.

In 1847, four Oblate Catholic missionaries arrived at Fort Walla Walla. The missionaries were befriended by Peopeo Moxmox, who provided them with land for their new mission, St. Rose. The missionaries, however, did not find the Indians eager to convert. However, the American settlers in the region, most of whom were Protestants, hated Catholics as much as they hated Indians. By befriending Catholics, Peopeo Moxmox did not endear himself to the Americans.

In 1848, an American militia group under the leadership of Reverend Cornelius Gilliam, who is described as “a fire-and-brimstone preacher,” left The Dalles seeking to kill Indians (and perhaps some Catholic bishops and priests). The ragtag militia group was lead by a peace delegation carrying white flags.

The militia group had their first encounter with Indians at Sand Hollow where they battled Cayuse warriors under the leadership of Five Crows for three hours without reaching a decisive victory. Following this battle, the Americans were more determined than ever to punish the Indians.

After a forced all night march, the militia found the Walla Walla and Palouse village of Peopeo Moxmox. While Reverend Cornelius Gilliam was informed that Peopeo Moxmox was friendly, he ordered his men gather up the stock that was grazing nearby. Needless to say, the Indians protested this action, and when the militia failed to stop, they defended their property rights. The militia soon found itself under attack by 400 seasoned warriors who had experience in fighting against the Blackfoot and Shoshone. The militia released the stock and retreated.

As a side note, it should be mentioned that Reverend Cornelius Gilliam accidentally killed himself when he removed his gun from the back of a wagon. The militia disbanded.

By the 1850s, there were a number of Indian leaders among the Plateau Indian nations who were calling for armed resistance to the American invasion. In 1854, Yakama leader Kamiakin, Walla Walla leader Peopeo Moxmox, and Nez Perce war chief Apash Wyakaikt (Looking Glass) convened a large intertribal council in Oregon’s Grande Ronde Valley. The tribes spent five days listening to Kamiakin’s account of what was happening to the Indian nations west of the Cascade Mountains. Kamiakin urged a confederacy so that the Americans (suyapos) could be fought with a united front. Kamiakin told the council:

“We wish to be left alone in the lands of our forefathers, whose bones lie in the sand hills and along the trails, but a pale-faced stranger has come from a distant land and sends word to us that we must give up our country, as he wants it for the white man. Where can we go? There is no place left.”

Reaction to the call for war was mixed, with many leaders calling for peace. The proposed confederacy did not materialize.

In 1855, Washington Territorial Governor Isaac Stevens called a treaty conference at Walla Walla for the purpose of creating two reservations for all of the Indian nations in the region. In his essay in As Days Go By: Our History, Our Land, and Our People—The Cayuse, Umatilla, and Walla Walla, Antone Minthorn reports:

“All the tribes attending the Treaty Council understood that the U.S. government was forcing the Indians to choose a place for a reservation to prevent war and to stay out of the way of the settlers rushing in to make claims on their land.”

As usual, the Americans knew little of the Indian cultures and histories, assumed that the Indian leaders were unaware of the long history of American betrayals of Indian treaties, and so they blatantly lied to the Indians. The style of “negotiating” used by Governor Stevens relied upon lying, arrogance, ignorance, and bullying. According to historian Alvin Josephy, in his report on the Walla Walla Council in The Western American Indian: Case Studies in Tribal History:

“The transparency of the speeches of Governor Stevens and Superintendent Palmer is so obvious that it is a wonder the commissioners could not realize the ease with which the Indians saw through what they were saying. One can only assume either that their ignorance of the Indians’ mentality was appalling or that they were so intent on having their way with the tribes that they blinded themselves to the flagrancy of their hypocrisy.”

The Americans were apparently unaware that the Indians of the Plateau had been told the story of the Trail of Tears for years by the Iroquois, the Delaware, and the Plains Indians. Peopeo Moxmox told the Americans:

“You have spoken in a manner partly tending to evil. Speak plain to us.”

As usual, the result of the Walla Walla “peace” treaty was to nurture and give birth to warfare in the region. And this war, brought about and encouraged by the Americans led to the brutal death of Peopeo Moxmox, a chief who had been friendly toward the Americans and an advocate of peace. In his book The Nez Perce Indians and the Opening of the Northwest, historian Alvin Josephy calls Peopeo Moxmox:

“[A]n Indian leader with every reason to turn with bitterness against the Americans, but a man who had remained to the end a peace chief, and not a warrior.”

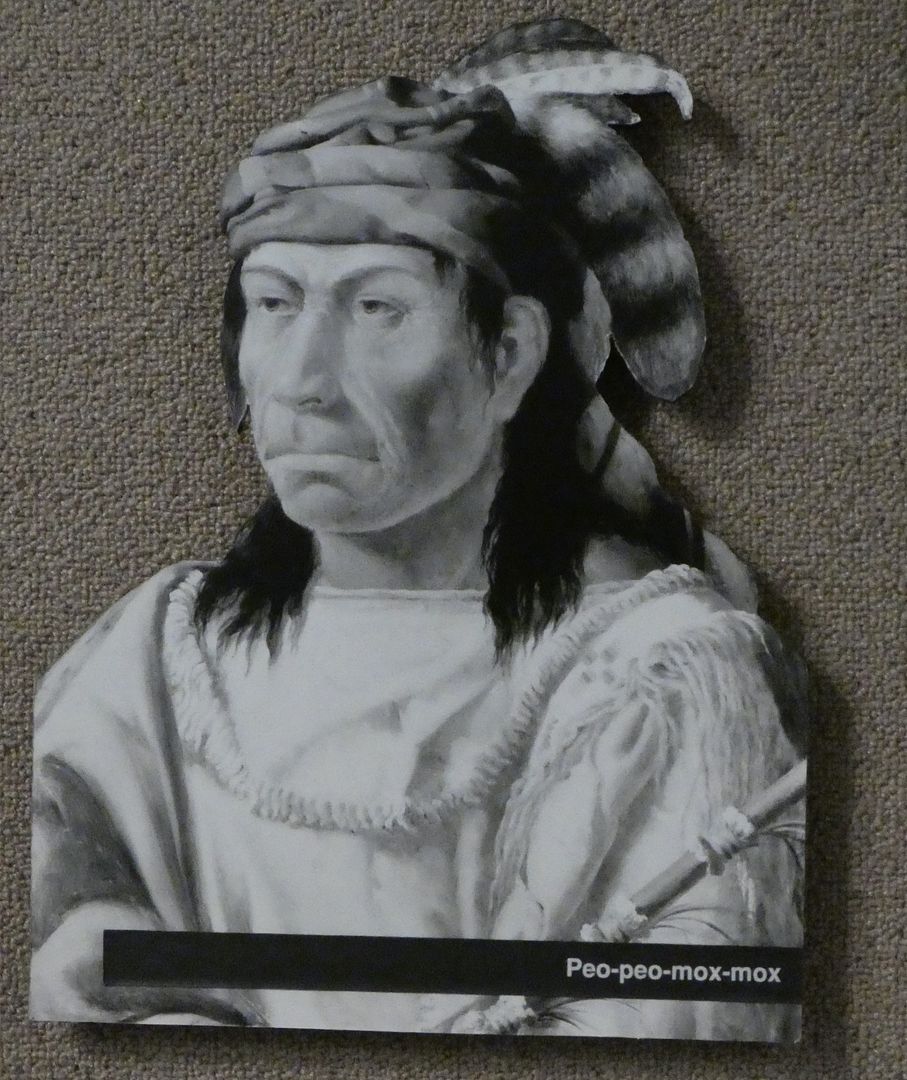

Shown above is a portrait of Walla Walla leader Peopeo Moxmox which is on display in the East Benton County Museum in Kennewick, Washington.

Shown above is a portrait of Walla Walla leader Peopeo Moxmox which is on display in the East Benton County Museum in Kennewick, Washington.

Indians 101

Indians 101 is a series exploring American Indian biographies, cultures, histories, arts, and current concerns. More biographies from this series:

Indians 101: Henry Roe Cloud, Winnebago Educator

Indians 101: Red Jacket, Seneca Sachem

Indians 101: Looking Glass, Nez Perce Chief

Indians 101: Francis La Flesche, Omaha Ethnographer

Indians 101: Kennekuk, Kickapoo Leader and Prophet

Indians 101: Gertrude Simmons Bonnin, Writer, Musician, and Activist

Indians 101: Susette La Flesche, Indian Activist

Indians 201: Natawista, a Trader's Wife