The National Museum of the United States Air Force in Dayton, Ohio includes displays of World War I memorabilia.

According to the Museum:

World War I began in August 1914. In contrast to the United States, which had fewer than a dozen military airplanes at that time, Germany, France and England had 180, 136 and 48 aircraft, respectively. These nations soon discovered the immense value of aerial reconnaissance to their armies and a race began to build up their flying forces. Within a short time, each realized the importance of denying this aerial reconnaissance to the enemy; thus aerial combat was born. During the first several years of the war, great strides were made in airplane design and performance, in the development of gunnery and bombing equipment, and in aerial combat tactics and techniques. The airplane became a true weapon of destruction over the battlefield of Europe.

Shown above are some of the squadron emblems.

Shown above are some of the squadron emblems.

Eugene Jacques Bullard

According to the Museum:

In August of 1917 Eugene Jacques Bullard, an American volunteer in the French army, became the first African American military pilot and one of only a few blacks pilot in World War I. Born in Columbus, Ga., on Oct. 9, 1894, Eugene Bullard left home at the age of 11 to travel the world, and by 1913, he had settled in France as a prizefighter. When WWI started in 1914, he enlisted in the French Foreign Legion and rose to the rank of corporal. For his bravery as an infantryman in combat, Bullard received the Croix de Guerre and other decorations.

During the Battle of Verdun in 1916, Bullard was seriously wounded. While recuperating, he accepted an offer to join the French air force as a gunner/observer, but when he reported to gunnery school, he obtained permission to become a pilot. After completing flight training, Bullard joined the approximately 200 other Americans who flew in the Lafayette Flying Corps, and he flew combat missions from Aug. 27 until Nov. 11, 1917. He distinguished himself in aerial combat, as he had on the ground, and was officially credited with shooting down one German aircraft. Unfortunately, Bullard -- an enlisted pilot -- got into a disagreement with a French officer, which led to his removal from the French air force. He returned to his infantry regiment, and he performed non-combatant duties for the remainder of the war.

After the war, Bullard remained in France as an expatriate. When the Germans invaded France in May 1940, the 46-year-old Bullard rejoined the French army. Again seriously wounded by an exploding shell, he escaped the Germans and made his way to the United States. For the rest of World War II, despite his lingering injuries, he worked as a longshoreman in New York and supported the war effort by participating in war bond drives.

Bullard stayed in New York after the war and lived in relative obscurity, but to the French, he remained a hero. In 1954 he was one of the veterans chosen to light the “Everlasting Flame” at the French Tomb of the Unknown Soldier under the Arc de Triomphe, and in 1959, the French honored him with the Knight of the Legion of Honor.

On Oct. 13, 1961, Eugene Bullard died and was buried with full military honors in his legionnaire’s uniform in the cemetery of the Federation of French War Veterans in Flushing, N.Y. On Sept. 14, 1994, the Secretary of the Air Force posthumously appointed him a second lieutenant in the United States Air Force.

Shown above are Eugene Jacques Bullard’s medal. Bullard was an American volunteer in the French army and the first African American military pilot.

Shown above are Eugene Jacques Bullard’s medal. Bullard was an American volunteer in the French army and the first African American military pilot.

Shown above is Eugene Jacques Bullard

Shown above is Eugene Jacques Bullard

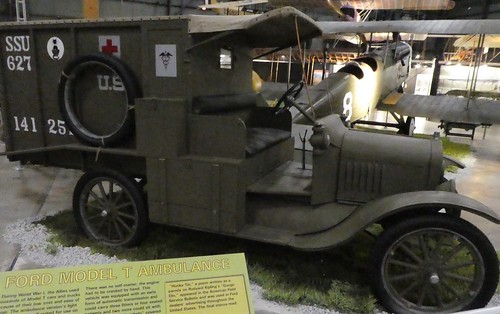

Ford Model T Ambulance

During World War I, the Allies used thousands of Model T cars and trucks because of their low cost and ease of repair. The ambulance version's light weight made it well-suited for use on the muddy and shell-torn roads in forward combat areas. If stuck in a hole, a group of soldiers could lift one without much difficulty. By Nov. 1, 1918, 4,362 Model T ambulances had been shipped overseas.

The light wooden body was mounted on a standard Model T auto chassis. The 4-cylinder engine produced about 20 hp. There was no self-starter; the engine had to be cranked by hand. This vehicle was equipped with an early form of automatic transmission and could carry three litters or four seated patients and two more could sit with the driver. Canvas "pockets" covered the litter handles that stuck out beyond the tailgate. Many American field service and Red Cross volunteer drivers, including writers Ernest Hemingway and Bret Harte and cartoonist Walt Disney drove Model T ambulances.

More World War I museum exhibit photo tours

Museum of Flight: World War I Sopwith airplanes (photo diary)

Museum of Flight: World War I French, British, and American airplanes (photo diary)

Museum of Flight: World War I German airplane models (photo diary)

Museum of Flight: World War I multi-engine models (photo diary)

Museum of Flight: World War I seaplane models (photo diary)

Museum of Flight: World War I French and British airplane models (photo diary)

Museum of Flight: World War I memorabilia (photo diary)

Veterans Memorial Museum: World War I (Photo Diary)