World War I was the first “mechanized” war, with tanks and trucks on the ground and airplanes in the sky. During this time, aviation and airplanes developed dramatically. The Early Years Gallery of the National Museum of the United States Air Force in Dayton, Ohio features several World War I airplanes.

According to the Museum:

World War I began in August 1914. In contrast to the United States, which had fewer than a dozen military airplanes at that time, Germany, France and England had 180, 136 and 48 aircraft, respectively. These nations soon discovered the immense value of aerial reconnaissance to their armies and a race began to build up their flying forces. Within a short time, each realized the importance of denying this aerial reconnaissance to the enemy; thus aerial combat was born. During the first several years of the war, great strides were made in airplane design and performance, in the development of gunnery and bombing equipment, and in aerial combat tactics and techniques. The airplane became a true weapon of destruction over the battlefield of Europe.

Avro 504K

According to the Museum:

In July 1913, the British A.V. Roe (Avro) Co. tested its first model 504 aircraft, and numerous variants followed—based upon the type of engine installed. The Avro 504 briefly saw combat in 1914-1915, but was quickly identified as obsolete and relegated to training duty. As a trainer, it gained fame for its simple, sturdy construction and superior handling—characteristics which made the Avro 504 one of the most impressive and widely produced training aircraft of World War I.

After America entered WW I, it took many months to build the training facilities needed by the US Army Air Service. Meanwhile, many American student pilots went overseas for flight training. Those sent to Great Britain learned on the Avro 504K trainer before advancing to combat aircraft. The Air Service eventually established its main training center at Issoudun, France, and in July 1918, the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) commanders ordered 52 Avro 504K aircraft for teaching aerobatics at Issoudun. After the war, the Air Service brought a few Avro 504K aircraft back to the United States, and they remained in training service for several years.

This aircraft had a top speed of 95 mph, and a ceiling of 13,000 feet.

Nieuport 28

According to the Museum:

The French-built Nieuport 28 became the first fighter airplane flown in combat by pilots of the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) in World War I. On April 14, 1918, resulted in two victories when Lts. Alan Winslow and Douglas Campbell of the 94th Aero Squadron each downed an enemy aircraft -- the first victories by an AEF unit.

The lightly built Nieuport 28 developed a reputation for shedding its upper wing fabric in a dive, and by the spring of 1918, many considered the Nieuport 28 obsolete. Even so, American pilots maintained a favorable ratio of victories to losses with it. Many American aces of WWI, including 26-victory ace Capt. Eddie Rickenbacker, flew the Nieuport at one time or another in their careers. The less maneuverable, but faster and sturdier, SPAD XIII began replacing the Nieuport 28 in March 1918.

This aircraft had a top speed of 122 mph, a range of 180 miles, and a ceiling of 17,000 feet. It was powered by a Gnome N-9 rotary engine of 160 hp. It carried two Vickers .303 caliber machine guns.

The plane on display is a reproduction containing wood and hardware from an original Nieuport 28.

Fokker Dr.I

According to the Museum:

Few aircraft have received the attention given the Fokker Dr. I triplane. Often linked with the career of World War I's highest scoring ace, Germany's Rittmeister Manfred von Richthofen (the "Red Baron"), the nimble Dr. I earned a reputation as one of the best dogfighters of the war.

The German air force ordered the Fokker Dr. I in the summer of 1917, after the earlier success of the British Sopwith triplane. The first Dr. Is appeared over the Western Front in August 1917. Pilots were impressed with its agility, and several scored victories with the highly maneuverable triplane. Von Richthofen score 19 of his last 21 victories were achieved while he was flying the Dr. I. By May 1918, however, the Dr. I was being replaced by the newer and faster Fokker D. VII.

This aircraft had a top speed of 103 mph, a range of 185 miles, and a ceiling of 19,685 feet. It was powered by a Oberursel Ur II engine of 110 hp or a LeRhone of 110 hp. It carried two 7.92mm Spandau LMG 08/15 machine guns.

A total of 320 of these airplanes were built and none have survived. The airplane on display is a reproduction.

Fokker D.VII

According to the Museum:

First appearing entering combat in May 1918, the Fokker D. VII quickly showed its superior performance over Allied fighters. With its high rate of climb, higher ceiling and excellent handling characteristics, German pilots scored a remarkable 565 victories over Allied aircraft during the month of August alone.

Designed by Reinhold Platz, the prototype of the D. VII flew in a competition against other new fighter aircraft in early 1918. After Baron Manfred von Richthofen, the famous Red Baron, flew the prototype and enthusiastically recommended it, the D. VII was chosen for production. To achieve higher production rates, Fokker, the Albatross company and the Allgemeine Elektrizitats Gesellschaft (AEG) all built the D. VII. By war's end in November 1918, these three companies had built more than 1,700 aircraft.

This aircraft had a top speed of 120-124 mph, and a ceiling of 18,000 feet. It was powered by a Mercedes engine of 160 hp or a BMW of 185 hp. It carried two 7.92mm Spandau machine guns.

The plane on display is a reproduction.

Sopwith F.1 Camel

According to the Museum:

The British Sopwith F.1 Camel shot down more enemy aircraft than any other Allied World War I fighter. Best characterized by its unmatched maneuverability, the camel was difficult to defeat in a dogfight. Tricky handling characteristics, however, made the Camel a dangerous aircraft to fly. More than 380 men died training to fly the aircraft, nearly as many who died while operating it in combat.

The Camel first went into action in June 1917 with No. 4 Squadron, Royal Naval Air Service where it was hailed for its superiority over German aircraft. Earning a fearsome reputation, the Camel was widely distributed through British aviation squadrons and later also equipped several U.S. Army Air Service squadrons.

Two of these squadrons, the 17th and 148th Aero Squadrons, saw combat while assigned to British forces during the summer and fall of 1918. Armed with their Camel fighters, these units counted a number of high-scoring American aces among their ranks. Famous aces Capt. Elliot White Springs, Lt .George A. Vaughn, and Lt. Field E. Kindley all gained fame with the 17th and 148th Aero Squadrons. Another American unit, the 185th Aero Squadron, used the Camel as a night fighter during the last month of the war.

This aircraft had a top speed of 112 mph, a range of 300 miles, and a ceiling of 19,000 feet. It was powered by a Clerget rotary engine of 130 hp. It carried two Vickers .303 caliber machine guns.

A total of 5,490 Camels were built. The airplane on display is a reproduction.

Halberstadt CL IV

According to the Museum:

Introduced into combat during the last great German offensive of World War I, the CL IV supported German troops by attacking Allied ground positions. Equipped with both fixed and flexible machine guns, hand-dropped grenades and small bombs, the CL IV proved very effective in this role, but it lacked the armor necessary for protection against ground fire.

The CL IV became a hunted target of Allied pursuit squadrons, but it gave a very good account of itself in dogfights. A versatile machine, the CL IV also performed as an interceptor against Allied night bombing raids and served as a night bomber against troop concentrations and airfields near the front lines.

This aircraft had a top speed of 112 mph, a range of 300 miles, and a ceiling of 21,000 feet. It was powered by a Mercedes D III 6-cylinder in-line, water-cooled engine of 160 hp. It carried one or two fixed 7.92mm Spandau machine guns, and one flexible 7.92mm machine gun.

The airplane on display has been restored from a badly deteriorated airplane.

Spad XIII C.1

According to the Museum:

In 1916 a new generation of German fighters threatened to win air superiority over the Western Front. The French aircraft company, Société pour l'Aviation et ses Dérives (SPAD), responded by developing a replacement for its highly successful SPAD VII. Essentially a larger version of the SPAD VII with a more powerful V-8 Hispano-Suiza engine, the prototype SPAD XIII C.1 ["C" designating Chasseur (fighter) and "1" indicating one aircrew] first flew in March 1917.

With its 220-hp engine, the SPAD XIII reached a top speed of 135 mph -- about 10 mph faster than the new German fighters. It carried two .303-cal. Vickers machine guns mounted above the engine. Each gun had 400 rounds of ammunition, and the pilot could fire the guns separately or together. Technical problems hampered production until late 1917, but nine different companies built a total of 8,472 SPAD XIIIs by the time production ceased in 1919.

Since the United States entered World War I without a combat-ready fighter of its own, the U.S. Army Air Service obtained fighters built by the Allies. After the Nieuport 28 proved unsuitable, the Air Service adopted the SPAD XIII as its primary fighter. By the war's end, the Air Service had accepted 893 SPAD XIIIs from the French, and these aircraft equipped 15 of the 16 American fighter squadrons. Today, Americans are most familiar with the SPAD XIII because many of our aces -- like Rickenbacker and Luke -- flew them during WWI.

Standard J-1

According to the Museum:

The Standard Aircraft Co. J-1 was a two-seat primary trainer used by the U.S. Army Air Service to supplement the JN-4 Jenny. Similar in appearance to the JN-4, the J-1 was more difficult to fly and never gained the popularity of the legendary Jenny.

Standard developed the J-1 from the earlier Sloan and Standard H-series aircraft designed by Charles Healey Day. Four companies -- Standard, Dayton-Wright, Fisher Body and Wright-Martin -- built 1,601 J-1s. The government cancelled about 2,700 more J-1s on order after the signed of the Armistice in November 1918.

This aircraft had a top speed of 72 mph, a range of 235 miles, and a ceiling of 5,800 feet. It was powered by a Curtiss OXX-6 engine of 100 hp.

The fabric covering on the fuselage has been removed to illustrate the wire-braced wooden construction typical for aircraft of that time. It also reveals the dual controls and relatively simple cockpit instrumentation. The black tank in front of the forward cockpit is the fuel tank.

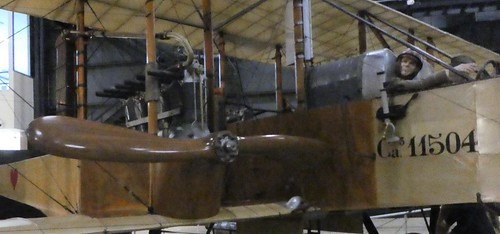

Caproni CA.36

According to the Museum:

During World War I, Italian aeronautical engineer Gianni Caproni developed a series of multi-engine heavy bombers that played a key role in the Allied strategic bombing campaign. His bombers were produced not only in Italy, but also in France and the United States.

In late 1914 Caproni designed the Ca. 31, powered by three Gnome rotary engines. The following year, Caproni produced a new version, the Ca. 32. Very similar to the Ca. 31, it had three FIAT 100-hp water-cooled in-line engines. Three months after Italy's entry into WWI, the first Ca. 32s attacked an Austrian air base at Aisovizza, and by the end of the year, regular raids were being mounted against other Austrian targets.

Caproni continued to refine his successful design with the introduction of the Isotta-Fraschini powered Ca. 33. Toward the end of the war the definitive version, the Ca. 36, went into production. Changes from the Ca. 33 were small but included five-section wings that made disassembly and surface transportation easy. Ca. 36s remained in Italian Air Force service as late as 1929.

This aircraft had a top speed of 87 mph, a range of 372 miles, and a ceiling of 14,765 feet. It was powered by three Isotta-Fraschini V.4B 150hp, water-cooled, 6-cylinder engines. It carried two Revelli 6.5mm machine guns and 1,764 pounds of bombs. It had a crew of four.

A restored plane is on display.

Thomas-Morse S4C Scout

According to the Museum:

The Thomas-Morse Scout became the favorite single-seat training airplane for U.S. pilots during World War I. The Scout first appeared with an order for 100 S4Bs in the summer of 1917. The U.S. Army Air Service later purchased nearly 500 of a slightly modified version, the S4C. Dubbed the "Tommy" by its pilots, the plane had a long and varied career.

Tommies flew at practically every pursuit flying school in the United States during 1918. After the war ended, the Air Service sold them as surplus to civilian flying schools, sportsman pilots and ex-Army fliers. Some were still being used in the mid-1930s for WWI aviation movies filmed in Hollywood.

This aircraft had a top speed of 95 mph, a range of 250 miles, and a ceiling of 16,000 feet. It was powered by LeRhone C-9 rotary engine of 80 hp. It carried one .30 caliber Marlin machine gun.

This is a restored aircraft.

Kettering Aerial Torpedo “Bug”

According to the Museum:

In 1917 Charles F. Kettering of Dayton, Ohio, invented the unmanned Kettering Aerial Torpedo, nicknamed the "Bug." Launched from a four-wheeled dolly that ran down a portable track, the Bug's system of internal pre-set pneumatic and electrical controls stabilized and guided it toward a target. After a predetermined length of time, a control closed an electrical circuit, which shut off the engine. Then, the wings were released, causing the Bug to plunge to earth -- where its 180 pounds of explosive detonated on impact.

The Dayton-Wright Airplane Co. built fewer than 50 Bugs before the Armistice, and the Bug never saw combat. After the war, the U.S. Army Air Service conducted additional tests, but the scarcity of funds in the 1920s halted further development.

Powered by a De Palma 4-cylinder 40 hp engine, it has a top speed of 120 mph and a range of 75 miles.

A full-size reproduction is on display.

More airplanes

Museum of Flight: World War I German airplanes (photo diary)

Museum of Flight: World War I Sopwith airplanes (photo diary)

Museum of Flight: World War I French, British, and American airplanes (photo diary)

Museum of Flight: The First Fighter Plane (photo diary)

Evergreen Aviation: Biplanes (photo diary)

Stonehenge Air Museum: Biplanes (Photo Diary)

Yanks Air Museum: Biplanes (Photo Diary)

WAAAM: Early Airplanes (Photo Diary)