In the last few weeks there have been many demonstrations and commemorations regarding the Nakba, the 'Catastrophe' of 1948 when over 800,000 Palestinians were ethnically cleansed from their homes. But this week, the commemorations have increased, coinciding with the Israel's Independence declaration, May 14, 1948 (and the visit of the Pope to Israel/Palestine, of course). What is most often covered in regard to the Nakba are the commemorations by Palestinians under occupation, as well as Palestinians in the diaspora. We will look at them eventually, but first, let's discuss the Palestinian citizens of Israel, for whom the Nakba is just as real, and who face increasing amounts of pressure and violence from the state of Israel.

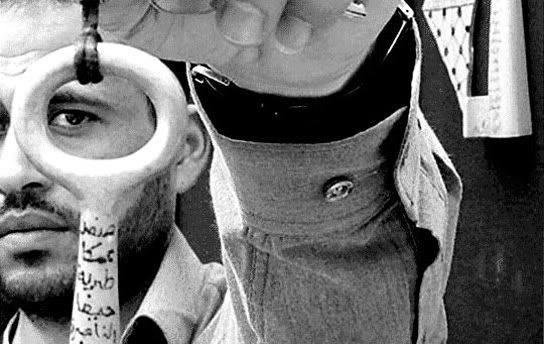

Nasser Flaifel carries his handmade "key of return" ornamented with the names of Palestinian cities. (Sami Abu Salem, WAFA)

The Palestinian citizens of Israel have been designated by the state of Israel as 'Israeli Arabs,' mainly as a means of de-nationalizing their identity. With the refugees from Palestine outside their borders and not under their direct control, here was the remainder of Palestinian citizenry left in what had become Israel, and the last thing that they wanted to do was to acknowledge the existence of Palestine and Palestinians within the state of Israel. As Golda Meir stated years later they simply did not exist, therefore referring to them as such was not even considered. To this day, many Zionists and/or Jewish Israelis refer to Palestinians simply as 'Arabs' and they most certainly do not recognize the reality of Palestine within Israel itself. But let's hear it from some actual Palestinian citizens of Israel, why don't we;

History of the Palestinians in Israel

Today, Palestinian citizens of Israel comprise close to 20% of the total population of the country, numbering over 1,000,000. They live predominantly in villages, towns, and mixed Arab-Jewish cities in the Galilee region in the north, the Triangle area in central Israel, and the Naqab (Negev) desert in the south. A part of the Palestinian people who currently live in the West Bank, Gaza Strip and the Diaspora, they belong to three religious communities: Muslim (81%), Christian (10%), and Druze (9%). Under international instruments to which Israel is a state party, they constitute a national, ethnic, linguistic, and religious minority.

Establishment of the state

In 1947, the Palestinians comprised some 67% of the population of Palestine. On 14 May 1948, the State of Israel was established. During the Arab-Israeli war that immediately followed, approximately 780,000 of the pre-1948 Palestinian population fled or were expelled, forced to become refugees in the neighboring Arab states and in the West. Of the 150,000 Palestinians who remained in the new state, approximately 25% were displaced from their homes and villages and became internally displaced persons as the Israeli army destroyed over 400 Arab villages. As a result of the war, the Palestinian population in Israel found itself disoriented and severely weakened. They had been effectively transformed from members of a majority population to a minority in an exclusively Jewish state. They lacked political as well as economic power, as their leadership, as well as their professional and middle classes, were refused the right to return and compelled to live outside of the state.

Successive Israeli governments maintained tight control over the community, attempting to suppress Palestinian/Arab identity and to divide the community within itself. To that end, Palestinians are not defined by the state as a national minority despite UN Resolution 181 calling for such; rather they are referred to as "Israeli Arabs," "non-Jews," or by religious affiliation. Further attempts have been made to split the Palestinian community into "minorities within a minority" through separate educational curricula, disparate employment and academic opportunities, and the selective conscription of Druze and some Bedouin men to military service. Israeli discourse has legitimated the second-class status of Palestinian citizens on the basis that the minority population does not serve in the military; however, the selective conscription of Druze and some Bedouin has not prevented discrimination against them.

I will point out one slight error in the above information. If one looks at the current studies done on the subject of the Nakba by both Israeli and Palestinian historians, it is clear that the expulsion did not begin on May 14th. It actually began months before that, as the Yishuv began to ethnically cleans the Palestinian villages in and around Jewish settlements. By the time Israel proclaimed its independence, roughly 300,000 Palestinians were expelled, followed by hundreds of thousands more Palestinians in the following months. It even continued as the actual fighting between Israel and Jordan had long since ended; the Israeli town of Ashkelon was before it the Palestinian town of Majdal. The Palestinians there were forced to flee to the Gaza Strip in 1950. Here are two accounts;

History Erased

By Meron Rapoport

In July 1950, Majdal - today Ashkelon - was still a mixed town. About 3,000 Palestinians lived there in a closed, fenced-off ghetto, next to the recently arrived Jewish residents. Before the 1948 war, Majdal had been a commercial and administrative center with a population of 12,000. It also had religious importance: nearby, amid the ruins of ancient Ashkelon, stood Mash'had Nabi Hussein, an 11th-century structure where, according to tradition, the head of Hussein Bin Ali, the grandson of the Prophet Muhammad, was interred; his death in Karbala, Iraq, marked the onset of the rift between Shi'ites and Sunnis. Muslim pilgrims, both Shi'ite and Sunni, would visit the site. But after July 1950, there was nothing left for them to visit: that's when the Israel Defense Forces blew up Mash'had Nabi Hussein.

al majdal is named after one of the Palestinian cities in the south of Palestine, home to some 11,000 Palestinian women, men, youth, and children, which was brought to a sudden end by the forceful superimposure of the Israeli city of Ashkelon. Unlike many other towns and villages in Palestine, not all of the people of Majdal Jad, as it was known, had vacated their town during the war of 1948. More than 1,500 residents remained steadfast until 1950, when they were finally evicted by a combination of Israeli military force and bureaucratic measures reminiscent of the current Israeli policy of ethnic cleansing applied against the Palestinian inhabitants in the eastern areas of occupied Jerusalem, in particular, and against Palestinians remaining in the area of historic Palestine. Thus, Palestinians of Majdal Jad were turned into refugees, most of them finding shelter in the nearby Gaza Strip. Like other Palestinian refugees, they have not disappeared. They have remained close to their homes and lands. Of old age now, they, their children and grandchildren have built new hopes and dreams based on the international recognition of their right of return, and struggled for the day when they would live a free citizens in al-Majdal/Ashkelon.

The Palestinians citizens of Israel, the ones that are refugees from al-Nakba, they are referred to as 'present absentees.' The 'absentees' are the ones that were expelled/fled in 1948 and are now outside the pre-1967 borders of Israel, from Balata Refugee Camp to Sabra and Shatila, and who knows, maybe down the street from you. The 'present absentees' are the ones that remained within the state, but since they were away from their home, or forced away from it, they are essentially internal refugees. Pretty Orwellian, no?

So the 'Israeli Arabs' are also Palestinians, which is slowly becoming clear to the news media of the world, despite their clinging to such terms, and they have, and they will continue to mark this day as crucial to their identity. Here's a few media notes on this years commemorations so far;

Arab-Israelis march for right of return

As Israel celebrated its 61st anniversary, some 2,000 people demonstrated on Wednesday for Arab-Israelis' right of return to the lands from which they were chased in 1948. The protest took place on the site of Al-Kafrayn, an Arab village among the more than 500 that were razed by Israeli forces at the time of the creation of the Jewish state in 1948.

Family members of some of the refugees visited sites of demolished villages on Wednesday just as Israel celebrated the 61st anniversary -- in the Hebraic lunar calender -- of its creation. "We have come to tell Israelis we will never forget," Fatima Chalabi, one of the protesters, told AFP.

Israeli Arabs mark 61st anniversary of Nakba

By Yoav Stern and Jack Khoury, Haaretz Correspondents

Hundreds of Israeli Arabs on Wednesday visited the sites of Palestinian villages that had been demolished during the War of Independence as part of the Nakba Day events, which commemorate the defeat of the Palestinian Arab community in the war.

In Israel, Jews and Arabs aim to bridge 'independence' and 'catastrophe' narratives

"I felt after this last war in Gaza, I couldn't just celebrate Independence Day as usual, so I was glad to find another framework entirely," says Beni Gassenbauer, a dentist who lives in Jerusalem and immigrated to Israel from France 30 years ago. "I didn't see myself staying in Jerusalem and having a party as if nothing has happened."

Still, the idea of sharing the most important secular holidays in the Israeli calendar – Tuesday was Memorial Day, honoring war veterans and victims of terrorism, and Wednesday is Independence Day – with Palestinians commemorating the Nakba (officially celebrated May 13 this year) was one he felt he'd do better to keep from his family.

"My family is very right-wing, and we find it harder and harder to speak about politics," Dr. Gassenbauer says. "I didn't tell my father I was coming here."

But this commemoration and identification as Palestinians is threatened by violence and frightening legal action by the state of Israel it seems. Of course, last year there was the police riot at the march to the ruins of Saffuriya;

Rights groups accuse police of brutality during Nakba protest

By Yoav Stern, Haaretz Correspondent

Activists and Arab rights organizations are accusing the Israel Police of brutality against protesters during a procession marking Nakba day 10 days ago in a pilgrimage to the abandoned village of Saphoria in Tzipori.

Nakba day, meaning "day of the catastrophe" is an annual day of commemoration for the Palestinian people of the anniversary of the creation of Israel in 1948 (on the same day Israelis celebrate independence), which resulted in their displacement from their land.

At a press conference held Monday, the activists presented video footage and photographs showing police officers beating journalists and even smashing the head of one of the protesters who was already handcuffed and sitting on the ground.

And the video, of course

more video here

And now with Netanyahu and Lieberman in office, can we expect more of the same? Actually, not surprisingly, it seems that things are going to get worse, before they get better;

Lieberman's party proposes ban on Arab Nakba

Foreign Minister Avigdor Lieberman's party wants to ban Israeli Arabs from marking the anniversary of what they term "the Catastrophe" or Nakba, when in 1948 some 700,000 Arabs lost their homes in the war that led to the establishment of the state of Israel. The ultranationalist Yisrael Beitenu party said it would propose legislation next week for a ban on the practice and a jail term of up to three years for violators.

The initiative could fuel racial tensions stoked by Lieberman's February election campaign call to make voting or the holding of public office in Israel contingent on pledging loyalty to the Jewish state. Arabs, who make up 20 percent of Israel's population, said the allegiance demand was aimed at them and accused Lieberman of racism.

This is not surprising, nor is it new or something we can just blame on Lieberman; it is sign of just how threatened the Zionist consensus and discourse on Israel and its 'Jewish character' has become, as well as the willful ignorance of many Jewish Israelis regarding the Nakba. One year it is beatings and police brutality, but next, we'll just try and make the whole observance of Nakba day illegal, how about that? Who knows, as the interview with Benny Morris indicates, 'transfer' is still an option in the minds of many; racist minds, of course,

Including the expulsion of Israeli Arabs?

"The Israeli Arabs are a time bomb. Their slide into complete Palestinization has made them an emissary of the enemy that is among us. They are a potential fifth column. In both demographic and security terms they are liable to undermine the state. So that if Israel again finds itself in a situation of existential threat, as in 1948, it may be forced to act as it did then. If we are attacked by Egypt (after an Islamist revolution in Cairo) and by Syria, and chemical and biological missiles slam into our cities, and at the same time Israeli Palestinians attack us from behind, I can see an expulsion situation. It could happen. If the threat to Israel is existential, expulsion will be justified."

As Americans, we have the shame of the treatment of Japanese-Americans in WWII, and among others, the horrible treatment of Muslims, Middle Easterners and other immigrants and citizens after 9/11. But here a respected 'liberal' Israeli talks of expelling over 1 million of its citizens, and he us by no means the only one (and now of course, we have Lieberman in office to administer the loyalty tests, don't we?).

The question for us all, Jews, Americans, Israelis, Democrats, Republicans and the like, is what does this mean for us? Why is the Nakba important? My answer is that because the Nakba is not over and continues to the present moment, and because recognition of the Nakba is what is needed to reach real peace and justice.

Many people, of course, think that if we just get back to those 1967 lines and such, then all will be well. I am not one of those folks. For some time, I only saw the conflict through the Zionist narrative and historiography. This has been largely revealed to be mostly mythological, and has been debunked by a variety of scholars, including, of course Israeli academics. See here how this is summed up;

In Beyond Chutzpah I argued that across the political spectrum historians have now reached a broad consensus on the Israel-Palestine conflict's origins. A recent study strikingly confirms this thesis. Shlomo Ben-Ami was Israel's Foreign Minister and key Israeli negotiator at the Camp David and Taba meetings in 2000-1. In his new book, Scars of War, Wounds of Peace: The Israeli-Arab Tragedy (Oxford: 2006), Ben-Ami covers a lot of the same ground as my own Image and Reality of the Israel-Palestine Conflict (Verso: 2003). From the excerpts below readers will note that, although describing himself as "a Zionist, and an ardent one at that" (p. xii), Ben-Ami echoes many of my arguments, even citing the identical evidence.

And one can read the discussion the two of them had on Democracy Now, of course;

SHLOMO BEN-AMI: Well, you see, there is a whole range of new historians that have gone into the sources of — the origins of the state of Israel, among them you mentioned Avi Shlaim, but there are many, many others that have exposed this evidence of what really went on on the ground. And I must from the very beginning say that the main difference between what they say and my vision of things is not the facts. The facts, they are absolutely correct in mentioning the facts and putting the record straight.

One of the main issues that the new consensus has dealt with of course, is the Nakba, and how central this act of dispossession is to the conflict. It is central to Palestinians and their national identity, as the majority of them, close to 7 million by some counts, are refugees, and millions more are under direct occupation by Israel. It is also central to Zionism and the state of Israel, for as a settler-colonial nation, this dispossession was built into Zionism; in order to create a Zionist Jewish state in Palestine, it required the expulsion and/or subjugation of the indigenous Palestinian population. As Zeev Jabotinsky saw very clearly, Palestinians were not going to flee or give up their country without force, and as he put it, the Iron Wall;

"Zionist colonization, even the most restricted, must either be terminated or carried out in defiance of the will of the native [Palestinian] population. This colonization can, therefore, continue and develop under the protection of a force independent of the local population --an iron wall which the native [Palestinian] population cannot break through. This is, in to, our policy towards the Arabs. To formulate it any other way would be hypocrisy." (Expulsion Of The Palestinians, p. 28)

"They look upon Palestine with the same instinctive love and true favor the Aztecs looked upon Mexico or any Sioux looked upon his prairie. Palestine will remain for the Palestinians not a borderland, but their birthplace, the center and basis of their own national existence." (Righteous Victims, p. 36)

So, with the Lieberman government arguing to erase the Palestinian identity and basic rights of Israeli citizens, if not to 'transfer' them out of the state due to their lack of loyalty, what is the truly 'progressive' position? I would say that Shlomo Sand and Rabbi Rosen do an excellent job of summing it up;

What is so dangerous about Jews imagining that they belong to one people? Why is this bad?

"In the Israeli discourse about roots there is a degree of perversion. This is an ethnocentric, biological, genetic discourse. But Israel has no existence as a Jewish state: If Israel does not develop and become an open, multicultural society we will have a Kosovo in the Galilee. We must begin to work hard to transform our place into an Israeli republic where ethnic origin, as well as faith, will not be relevant in the eyes of the law. Anyone who is acquainted with the young elites of the Israeli Arab community can see that they will not agree to live in a country that declares it is not theirs. If I were a Palestinian I would rebel against a state like that, but even as an Israeli I am rebelling against it."

The question is whether for those conclusions you had to go as far as the Kingdom of the Khazars.

"I am not hiding the fact that it is very distressing for me to live in a society in which the nationalist principles that guide it are dangerous, and that this distress has served as a motive in my work. I am a citizen of this country, but I am also a historian and as a historian it is my duty to write history and examine texts. This is what I have done."

If the myth of Zionism is one of the Jewish people that returned to its land from exile, what will be the myth of the country you envision?

"To my mind, a myth about the future is better than introverted mythologies of the past. For the Americans, and today for the Europeans as well, what justifies the existence of the nation is a future promise of an open, progressive and prosperous society. The Israeli materials do exist, but it is necessary to add, for example, pan-Israeli holidays. To decrease the number of memorial days a bit and to add days that are dedicated to the future. But also, for example, to add an hour in memory of the Nakba [literally, the "catastrophe" - the Palestinian term for what happened when Israel was established], between Memorial Day and Independence Day."

and Rabbi Rosen,

As a Jew, as someone who has identified with Israel for his entire life, it is profoundly painful to me to admit the honest truth of this day: that Israel’s founding is inextricably bound up with its dispossession of the indigenous inhabitants of the land. In the end, Yom Ha’atzmaut and what the Palestinian people refer to as the Nakhba are two inseparable sides of the same coin. And I simply cannot separate these two realities any more.

I can’t yet say what specific form my new observance of Yom Ha’atzmaut will take. I only know that it can’t be divorced from the Palestinian reality - or from the Palestinian people themselves. Many of us in the co-existence community speak of "dual narratives" - and how critical it is for each side to be open to hearing the other’s "story." I think this pedagogy is important as far as it goes, but I now believe that it’s not nearly enough. It’s not enough for us to be open to the narrative of the Nakhba and all it represents for Palestinians. In the end, we must also be willing to own our role in this narrative. Until we do this, it seems to me, the very concept of coexistence will be nothing but a hollow cliche.

Incorporation of the Nakba and Palestinian identity into the state of Israel? Making Israel a state of its citizens as opposed what it is now, a state of the Jewish people, which thereby disenfranchises roughly 20% of the population? I'd say that is the progessive response, indeed.

Yet there is the racism and brutality facing Palestinian citizens of Israel that I have pointed out; obviously, there are many Jewish Israelis frightened to death of such a bi-national reality, but the truth is that it is here, now, in Israel, and we need to confront it and the racism it stirs up. As some are pointing out, the ideal of Zionism and the 'Jewish nature' of the state may soon become a thing of the past;

the Zionist ideal is losing its hold within Israel itself. There are reportedly between 700,000 and one million Israeli citizens now living abroad, and emigration has outpaced immigration since 2007. According to Ian Lustick and John Mueller, only 69 percent of Israeli Jews say they want to remain in the country, and a 2007 poll reported that about one-quarter of Israelis are considering leaving, including almost half of all young people. As Lustick and Mueller note, hyping the threat from Iran may be making this problem worse, especially among the most highly educated (and thus most mobile) Israelis. Israeli society is also becoming more polarized...

In the end, this is the true strategic threat to Israel; the ever-increasing cost in violence that it takes to maintain Israel as a Jewish state, with as much territory as can be managed by it, but without an outright declaration of Apartheid rule (which would alienate the EU & the US & most American Jews) or a granting of citizenship to the occupied (which would end Israel as a Jewish State). This is what Israel is dealing with, and all else flows from it

And it all goes back to Israel's goal of being a Jewish State; this guided the Zionist movement and resulted in decades of colonization and the expulsion of the Palestinians, and more importantly, the 61 years since that they have been prevented from returning despite Israel's agreeing to abide by UN res 194. And it flows through the decision to retain the West bank and Gaza and the Labor-Likud settlement consensus, although with a significant problem; the Palestinians did not leave in 67 like 48, as they learned fast what happens when you leave (you can't come back). So now Israel is back to where it started; it has the land, but it does not want the people, and they are not leaving or giving up hope of someday returning.

I'll keep an eye on Nakba-related events as the week goes on, as Palestinians under occupation and the diaspora are very much a part of the issue. I also recently saw the film Salt of this Sea, which was excellent, and I very much would like to comment on it & my reactions to it. But I will leave you with two things. First, the basic mission statement of the Israeli group Zochrot, and then some material from The Institute for Middle East Understanding regarding the Nakba. I have been given full permission to repost as much of their site material as I like, so I'd like to start with some of the basics of the Nakba from their site.

So, here's Zochrot, a fabulous group; on your next trip to I/P, do a trip to a destroyed village with them;

Zochrot ["Remembering"]is a group of Israeli citizens working to raise awareness of the Nakba, the Palestinian catastrophe of 1948.

The Zionist collective memory exists in both our cultural and physical landscape, yet the heavy price paid by the Palestinians -- in lives, in the destruction of hundreds of villages, and in the continuing plight of the Palestinian refugees -- receives little public recognition.

Zochrot works to make the history of the Nakba accessible to the Israeli public so as to engage Jews and Palestinians in an open recounting of our painful common history. We hope that by bringing the Nakba into Hebrew, the language spoken by the Jewish majority in Israel, we can make a qualitative change in the political discourse of this region. Acknowledging the past is the first step in taking responsibility for its consequences. This must include equal rights for all the peoples of this land, including the right of Palestinians to return to their homes.

And next, the IMEU FAQ on the Nakba

1. What is the Nakba?

Nakba means "Catastrophe" in Arabic. It refers to the destruction of Palestinian society in 1948 when more than 700,000 Palestinians fled or were forced into exile by Israeli troops. Because the Palestinians were not Jewish, their presence and predominant ownership of the land were obstacles to the creation of a Jewish state. Their exodus, or Nakba, was already nearly half-complete by May 1948, when Israel declared its independence and the Arab states entered the fray.

Many Zionist leaders in Palestine openly favored "transfer" of the indigenous Palestinian population. Zionist forces used clashes that erupted as the British Mandate of Palestine came to an end in 1947-48 to rid as much of the land of its Palestinian inhabitants as possible. By the end of 1948, more than 700,000 Palestinians - two-thirds of the Palestinian population - fled in panic or were forcibly expelled. It is estimated that more than 50 percent fled under direct military assault. Others fled in panic as news of massacres - more than 100 civilians in the village of Deir Yassin and 200 in Tantura -- spread.

Zionist forces depopulated more than 450 Palestinian towns and villages, most of which were demolished to prevent the return of the refugees. (Figures of the number of towns and villages destroyed and depopulated vary. The Israeli daily Haaretz reports 530 lost villages.) These comprised three-quarters of the Palestinian villages inside the areas held by Israeli forces after the end of the war. The newly established Israeli government confiscated refugees' land and properties and turned them over to Jewish immigrants. Although Jews owned only about seven percent of the land in Palestine and constituted about 33 percent of the population, Israel was established on 78 percent of Palestine.

2. Why does the Nakba matter today?

The Nakba is the source of the still-unresolved Palestinian refugee problem. Today, there are more than 4 million registered Palestinian refugees worldwide. The majority of them still live within 60 miles of the borders of Israel and the West Bank and Gaza Strip where their original homes are located. Israel refuses to allow Palestinian refugees to return to their homes and to pay them compensation, as required by UN Resolution 194 of 1948.

Fifty-nine years after the Nakba, Palestinians continue to be denied their freedom and independence. In 1948, 78 percent of Palestine became the state of Israel. Today, the 22 percent that remains continues to be confiscated for the expansion of Israeli settlements and construction of the separation wall. This ongoing denial of Palestinian rights combined with U.S. financial and diplomatic support for Israel fuels anti-American sentiment abroad. A 2002 Zogby poll, conducted in eight Arab countries showed that "the negative perception of the United States is based on American policies, not a dislike of the West." The same poll showed that "the Palestinian issue was listed by many Arabs among the political issues that affect them most personally, in some cases topping such issues as health care and the economy." Resolution of the Palestinian issue would improve America's image and create lasting goodwill in the Arab and Muslim worlds.

3. Who are the Palestinian refugees?

Palestinian refugees are the individuals who were forced from their homes through deliberate Israeli actions since 1948, and their offspring. There are five primary groups of Palestinian refugees and displaced persons:

Palestinians displaced/expelled from their homes in 1948. This includes Palestinians registered as refugees with the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA), created in 1948 to aid Palestinians forced from their homes, and others who either were not eligible for international assistance or chose not to receive it.

Palestinians displaced for the first time in the June 1967 war from their places of origin in the West Bank, East Jerusalem, and the Gaza Strip.

Palestinians who left the Occupied Territories since 1967 and are prevented by Israel from returning due to revocation of residency, denial of family reunification, or deportation. Some are unwilling to return there owing to a well-founded fear of persecution. Israel deported more than 6,000 Palestinians from the Occupied Territories between 1967 and the early 1990s, revoked the residency rights of some 100,000, demolished 20,000 homes and refugee shelters, and confiscated several thousand square kilometers of land. [Refugee Facts and Figures]

Internally displaced Palestinians who left their homes or villages but remained in the area that became the state of Israel in 1948.

4. How many Palestinian refugees are there?

Reliable figures on the Palestinian refugee and displaced population are hard to find, as there is no centralized agency or institution charged with maintaining this information, and there is no uniform definition of a Palestinian refugee.

The United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA) administers the only registration system for Palestinian refugees, but it only includes those displaced in 1948 (and their descendants) who are in need of assistance and located in UNRWA areas of operation - West Bank, Gaza Strip, Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria. According to UNRWA, in 2006 there were 4,448,429 registered refugees.

BADIL, a Palestinian non-governmental organization, estimated that there were more than 7.2 million Palestinian refugees and displaced persons at the beginning of 2005. [Survey of Palestinian Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons 2004-2005]

This includes Palestinian refugees displaced in 1948 and registered for assistance with the UNRWA (4.3 million); Palestinian refugees displaced in 1948 but not registered for assistance (1.7 million); Palestinian refugees displaced for the first time in 1967 (834,000); 1948 internally displaced Palestinians (355,000); and, 1967 internally displaced Palestinians (57,000).

5. Where do the Palestinians live today?

In 2001, the Palestinian population worldwide was estimated by the Palestinian Academic Society for the Study of International Affairs (PASSIA) at almost 9.4 million. This included:

3,700,000 in the West Bank and Gaza Strip

1,213,000 in Israel

2,598,000 in Jordan

388,000 in Lebanon

395,000 in Syria

287,000 in Saudi Arabia

333,000 in other Arab states

216,000 in the Americas

275,000 in other countries

In 2004, the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics reported that the number of Palestinians worldwide had increased to 9.6 million.

According to the U.S. Department of State's "Country Reports on Human Rights Practices, 2004," 5.3 million Palestinians now live within the borders of former Palestine (that is, in Israel, the West Bank, East Jerusalem and Gaza Strip) as compared to 5.2 million Israeli Jews.

6. Do Palestinian refugees have a right to return to their homes?

Yes, they have the right, although Israel has so far refused to recognize this right. All refugees have an internationally recognized right to return to areas from which they have fled or were forced, to receive compensation for damages, and to either regain their properties or receive compensation and support for voluntary resettlement. This right derives from a number of legal sources, including customary international law, international humanitarian law (governing rights of civilians during war), and human rights law. The United States government has forcefully supported this right in recent years for refugees from Bosnia, Kosovo, East Timor and elsewhere.

In the specific case of the Palestinians, this right was affirmed by the United Nations Resolution 194 of 1948, and has been reaffirmed repeatedly by that same body, and has also been recognized by independent organizations such as Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch.

The U.S. government supported Resolution 194, and voted repeatedly to affirm it until 1993. At that time, the Clinton administration began to refer to Palestinian refugee rights as matters to be negotiated between the parties to the conflict.

Israel refuses to allow the refugees to return to villages, towns and cities inside Israel due to their ethnic, national and religious origin. Israel's self-definition as a Jewish state emphasizes the need for a permanent Jewish majority, Jewish control of key resources like land, and the link between Israel and the Jewish diaspora. Jewish citizens, residents and Jews from anywhere in the world are therefore granted special preferences regarding citizenship and land ownership.

A Palestinian family piles into a truck, becoming part of the Nakba in 1948. (UNWRA)