I'm reclined back in the passenger seat, eyes closed, the slap of the wipers and the drumroll of road spray off the tires splattering against the floor pan providing background as Randi Rhodes harangues a conservative caller who thought he'd come up with the perfect squelch to the tirade against the Bush administration Randi has been on for the last half hour.

The half-frozen slush we were driving through earlier has turned now to a solid drizzle of rain. I venture to open my eyes and steal a peek at the gray overcast. The disturbing scallop of darkness in the upper-right quadrant of vision in my right eye is still there, but it hasn't gotten any worse.

We are on I-80 between La Salle and the Quad Cities. There is still a long way to go before we get to Iowa City; we are going to be horribly late. I knew the ETA the nurse at the ophthalmologist's office had given them was spectacularly optimistic, and the road conditions have only made it worse.

Mrs. d is at the wheel. She senses I'm alert and smiles at me. "Well, Mr. d, life with you has certainly been an adventure."

I return a weak smile. "I guess I'm just not put together very well, Dear."

It's a double-edged sword, this trip. On the one hand, just six days before Christmas, every retinal specialist within a hundred miles of home is either gone on vacation or refuses to accept my group medical plan. Iowa City is the closest the ophthalmologists' office could find that would take my insurance -- no one wants to have anything to do with them except the attorneys general of several states.

On the other hand, the Eye Clinic at the University of Iowa hospital is one of the premier eye surgery facilities in the country. If we have to drive over three hours to get eye care, it would be hard to come up with a better destination.

Once upon a time, I considered myself a pretty healthy guy. Still do, in my mind at any rate, except that I'm dragging around this medical history more appropriate for an eighty-year-old man. A heart attack, a couple of open-heart surgeries, an irregular heartbeat controlled with medication, a stent, a detached retina in my left eye over a decade ago, cataract surgery and laser capsulotomies in both eyes, a handful of various minor procedures -- I won't bore you with all the details -- and now this. And healthy though I may imagine myself, there's a recognition that at any moment something could go horribly wrong, my run of good outcomes could elude me, and I could find myself among the disabled.

-------------------------

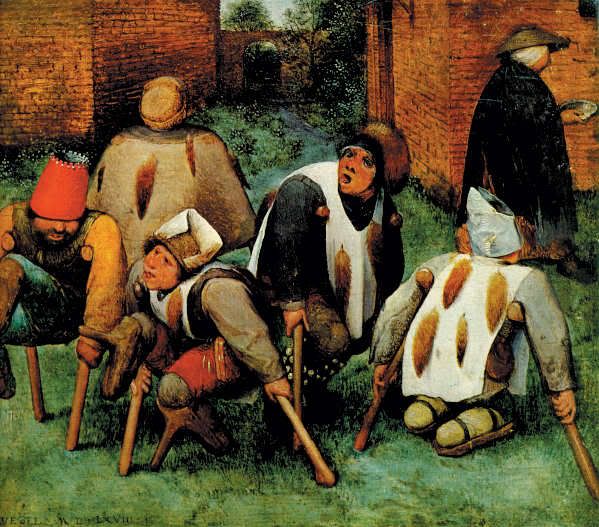

The Beggars (1568)

Pieter Brügel the Elder

|

Society long dealt with the disabled mostly by ignoring them, shunting them to the margins of society. And while the claim that the word "handicap" derived from a reference to panhandling by the disabled proves to have

no basis in historical fact, the truth is that for much of our history many disabled were, in fact, reduced to begging and reliance n other forms of charity for their survival.

While groups and individuals involved themselves charitably in the care of the disabled prior to the twentieth century, the demand far outstripped the resources, and "care" often translated into warehousing disabled individuals in institutions.

In 1900, the average lifespan in the United States was just 47 years, but improving medicine, sanitation, and nutrition quickly increased life expectancies in the twentieth century. Since the frequency of disabling conditions increases as a people grow older, the aging population resulted in an increasing number of Americans suffering disabilities.

Disabled man begging during the Great Depression

|

Following World War I, as thousands of soldiers returned to civilian life missing limbs, suffering "shell-shock", or poisoned by chemical weapons, the first government-funded vocational rehabilitation programs were initiated through the (Smith-Hughes) Vocational Education Act of 1917 and the Soldier's Rehabilitation Act of 1918 to help the veterans learn to deal with their disabilities.

The office of Vocational Rehabilitation was created by the Vocational Rehabilitation Act signed by Woodrow Wilson in 1920. Although states' participation was voluntary, by 1920, thirty-six of the then-forty-eight states were involved.

Early statistics maintained by VR indicated a modest expenditure of $12,000,000 had rehabilitated 45,000 people between 1921 and 1930. This averaged out to a cost of about $300 per person. By 1930, nine more states participated in the program. A total of 143 rehabilitation workers were employed in 44 states. VR's apparent efficiency led to its renewal in both 1930 and 1932 with increased levels of funding support. Vocational rehabilitation became a permanent program in 1935

[...]

[I]n 1940, Congress extended vocational rehabilitation services to people with disabilities working in sheltered workshops, those who were homebound, and those in the workforce who required services to remain employed. This significant increase in responsibility set the stage for a decade of greater funding and responsibility. VR grants increased 75% in 1940 and continued to increase throughout the 1940s. In July of 1943, services were broadened to include physical restoration and people with mental illness as clients

Disability Research Initiative: Freedom of Movement

The expansion of services and vocational training to the disabled continued through the nineteen-fifties and sixties as Mary Switzer guided the Office of Vocational Rehabilitation and effectively lobbied Congress to broaden -- such as through the Vocational Rehabilitation Act of 1954 -- both the services offered by the agency and the population eligible to receive those services.

The social movements of the middle-twentieth century had a profound impact on the push for recognition of the rights of many disadvantaged minorities, the disabled among them. As the movements that had begun with the civil rights movement of the nineteen-fifties manifested themselves and expanded, success fed upon success, and the empowerment of each successive group spurred agitation to correct deficiencies in society's attitudes toward, and treatment of, other groups.

The Civil Rights Movement of the 1960's gave rise to other civil rights movements, most notably the Women's Rights Movement and the Disability Rights Movement. While minorities and women were protected by civil rights legislation passed by the United States Congress during the 1960's, the rights of people with disabilities were not protected by federal legislation until much later.

[...]

The Civil Rights Act of 1968 includes Title VIII which prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, religion, national origin and sex in the sale and rental of housing. In this legislation, women have been recognized as a covered class, but the Fair Housing Act, like the Civil Rights Act of 1965, did not protect people with disabilities.

Mountain State Center for Independent Living: History of the ADA

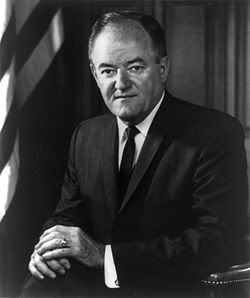

Hubert H. Humphrey (1911 - 1978)

Mayor, Senator (twice), Vice-President, Presidential candidate, champion of rights of the disabled.

|

The next significant action to establish the rights of disabled citizens, spearheaded by Senator Hubert Humphrey -- who had a first-hand acquaintance with the problems faced by the disabled via a grandchild with Down Syndrome -- was an attempt to amend the 1964 Civil Rights Act to include the disabled. There was, however, a potentially serious pitfall to using the Civil Rights Act to establish the rights of the disabled. Democratic congressional leaders were reluctant to expose the 1964 act to potential mischief on the floor of Congress.

The election of 1968 had represented a sea-change in American politics. Lyndon Johnson's prophecy that the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act had "lost the South for a generation" came to fruition as Richard Nixon defeated Humphrey in what was a bitter campaign from the very beginning of the primaries. The widespread public acceptance of the programs of New Deal and the Great Society began to unravel as cynical politicians convinced many working-class white voters that shiftless, freeloading ni**ers were being handed their hard-earned wages. While Democrats retained control of Congress, that caucus still included a significant contingent of conservative (and often racist) Dixiecrats. Laying the Civil Rights Act open to amendment was judged too great a risk. Ultimately, Humphrey's colleagues convinced him to agree to a different approach.

When the Vocational Rehabilitation Act came up for re-authorization, Congress crafted an even broader piece of legislation called the Rehabilitation Act of 1972. Congress sought to expand the program beyond its traditional employment focus by identifying ways to improve the overall lives of persons with disabilities: "the final goal of all rehabilitation services was to improve in every possible respect the lives as well as livelihood of individuals served." The new law would extend rehabilitation services to all persons with disabilities, give priority to those with severe disabilities, provide for extensive research and training for rehabilitation services, and coordinate federal disability programs. The act would be carried out by a Rehabilitation Services Administration (RSA) housed in the Department of Health, Education and Welfare (HEW).

National Council on Disability: Equality of Opportunity -- The Making of the Americans with Disabilities Act

The act departed significantly from tradition in more ways than simply dropping the word "vocational" from its title. It required federal executive branch agencies to utilize affirmative action and practice nondiscrimination in employment of the disabled. It also required the same of government contractors and subcontractors with federal contracts of more than $10,000. The act established an Architectural and Transportation Barriers Compliance Board (ATBCB) to ensure compliance with the

Architectural Barriers Act of 1968, requiring the government to identify and eliminate structural impediments to access by the disabled to facilities designed, built, altered, or leased with federal funds, and in accessibility to transportation and housing receiving federal funding, which had been ignored by the Nixon administration that had taken office five months after the Architectural Barriers Act's passage.

But what would prove to be the most contentious aspect of the bill as it wound its way through the legislative process was a provision to provide money to the states to fund programs to train the disabled to live independently, even absent prospects of being able to be trained for employment.

The Rehabilitation Act of 1972 was passed by Congress after a contentious battle; however, with Congress then out of session, President Nixon executed a pocket veto and killed the legislation. Nixon cited "congressional irresponsibility" in passing the $17 billion package, claiming the legislation would divert the program from its traditional objectives of vocational rehabilitation and medical treatment, and create numerous committees and commissions to administer the act.

Protests against Nixon's pocket-veto of the law followed quickly. Though generally small, they drew considerable attention -- it would be hard to conceive of a more sympathetic cohort. When the new Congress convened in January, 1973, they quickly assembled another bill, virtually identical to the original, which Nixon formally vetoed, again citing the costs of the independent-living provision. Congress once again went to work. Falling six votes short of passing the bill over the President's veto in the Senate, they were ultimately forced to compromise, eliminating the independent-living funding provisions from the bill. The bill was sent to the President, who signed it into law September 26, 1973. The Rehabilitation Act of 1973 was now the law of the land.

And part of that law was a little, hitherto unremarked snippet of text called Section 504.

Nondiscrimination Under Federal Grants and Programs

Sec. 504.(a) No otherwise qualified handicapped individual in the United States shall, solely by reason of his handicap, be excluded from the participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.

The Rehabilitation Act Amendments of 1973 (Link is to amended version)

The wording of Section 504 directly echoes Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. In its parallel language it adds disability to the conditions of "race, color, or national origin" for which discrimination by federally-funded programs is prohibited. Yet Section 504 is also a bit of a gobsmacker. According to accounts of the history of the Rehabilitation Act, Section 504 was never brought up by either side in the bitter debates over the bill in either chamber of Congress leading up to any of the three votes on the proposed law. Exactly how and why the provision got into the bill is apparently still a bit of a mystery -- speculation seems to center around congressional staffers inserting the wording without formal direction from elected representatives late in the bill's evolution. Nixon, in his two vetoes of the bill of the bill, never so much as mentioned Section 504 nor anything in it. It seems in some ways to be the ultimate piece of stealth legislation.

But what Section 504 was about to do would prove to be profound.

----------------------------

James Cherry was a young disabled man who suffered a rare degenerative muscular disease. But he was a very special kind of disabled person. He was a disabled person with a juris doctorate . A few months after the enactment of the Rehabilitation Act, Cherry began writing letters to the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare asking when they would be issuing regulations under Section 504.

Within a few months of enactment of Section 504, I inquired about the timeline for issuance of the 504 regulation. At the time I was a research patient at the National Institutes of Health (N.I.H.) in Bethesda, Maryland.

The responses I got from the U.S. Dept. of Health, Education and Welfare, whose job it should have been to issue the rules, were negative. DHEW contended that they had no explicit legal duty to issue a regulation under Section 504. Section 504 contained only 44 words and the legislative history was almost non-existent. DHEW spokespersons argued to me that Section 504 was a mere "policy statement" and required no regulatory action.

I aggressively disagreed. I didn't see mere "policy" -- I saw legal rights and power; and I wanted both.

Ragged Edge Online: James L. Cherry, "Cherry v. Mathews: 25 years and counting"

Although HEW was sandbagging Cherry and others who asserted it had a responsibility to regulate in the interest of the disabled, at the same time, President Gerald Ford -- appointed to the Vice-Presidency after Spiro Agnew's resignation two weeks after the Rehabilitation Act was signed into law and newly-ascended to the Presidency with Nixon's resignation in August, 1974 -- quietly directed DHEW's Office for Civil Rights (OCR) to draw up regulations under Section 504.

This was significant because such regulatory agencies as RSA, a potential alternative for writing the Section 504 regulations, focused mostly on community education and voluntary compliance among recipients of federal assistance. OCR, however, based its regulations on its history in dealing with civil rights and segregation, where firm legal foundations rather than mere voluntary compliance was necessary.

Under the leadership of John Wodatch, OCR prepared regulations that offered a new definition of disability, issued mandates for educating persons with disabilities in public schools, and demanded accessible buildings and transportation. But shortly after presenting the regulations to HEW Secretary Casper Weinberger on July 23, 1975, Weinberger was replaced by David Mathews, who was reputed to be "a cautious and indecisive man who tended to be more philosophical than pragmatic in running the department." Mathews did not oppose the regulations outright. But by demanding further analysis of the regulations, rather than taking the usual step of publishing the regulations as a proposal, Mathews delayed action.

National Council on Disability: Equality of Opportunity -- The Making of the Americans with Disabilities Act

Tired of the stalling, James Cherry, represented by Georgetown University's Institute for Public Interest Representation (INSPIRE), filed suit on February 13, 1976 to force DHEW to implement the regulation they believed to be required under Section 504.

Five months later, on July 19, 1976, the U. S. District Court ruled in Cherry's favor and directed DHEW to draw up the regulation. The court victory drew little notice.

The decision to keep quiet about my court victory was nothing more than a tactical decision in a larger strategy, because I realized that there was no real power, except the court, to back me if something went wrong. I didn't want DHEW to come under some outside pressure and appeal my case to the U. S. Court of Appeals. They didn't appeal, and DHEW remained under the federal court order in the Cherry case to develop and publish the Section 504 regulation. Sometimes, silence is golden.

The DHEW bureaucrats scurried around Washington crafting a version of the court-ordered regulation and tried to create some political opposition in Congress, but their efforts failed.

Ragged Edge Online: James L. Cherry, "Cherry v. Mathews: 25 years and counting"

For the next six months DHEW engaged in various stalling tactics, such as endless rounds of revision and public comment. When the regulation was finally presented to HEW Secretary Matthews in January of 1977, he refused to sign and implement it, instead taking the unprecedented step of forwarding it to Senate Committee on Labor and Public Welfare for further review. Frustrated, Cherry and INSPIRE again sued. A contempt of court ruling was issued January 18, 1977, but Matthews still failed to take action. Two days later, Jimmy Carter was sworn in as President and Matthews' term at DHEW was over. He had successfully run out the clock.

The incoming President nominated Joseph Califano, Jr. as Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare. Although Califano allegedly supported the Section 504 regulations in principle, he too delayed implementation.

Califano allegedly supported the concept of Section 504, but he too postponed action on the regulations; he wanted to review them before attaching his name. Califano worried especially about the costs associated with the statute and resisted the inclusion of drug and alcohol abusers as a protected class. When he proposed implementing a more limited concept of making individual programs accessible rather than demanding broad, structural changes, however, his actions drew the ire of persons with disabilities.

National Council on Disability: Equality of Opportunity -- The Making of the Americans with Disabilities Act

While James Cherry had found organizations advocating for persons with disabilities reluctant to join his civil-rights-based assault on the previous administration's failure recognize the requirement for Section 504 regulation, during his confrontation support for the regulation had coalesced from groups agitating for disability rights. Califano's failure to act triggered a reaction from the American Coalition of Citizens with Disabilities (ACCD), a group forged by a coalition of disability advocacy groups. Concerned that regulations were being watered down during the delay, on March 18, 1977, they delivered an ultimatum to President Carter that, if the regulations were not signed by April 4, public demonstrations would follow. The administration did not act.

On Monday, April 4, at 1:30 p.m., Frank Bowe, Dan Yohalem, Deborah Kaplan, and others met with Secretary Califano in his office. Califano tried to explain the delay and expressed support of public demonstrations to urge signing of the regulations. The disability activists, however, stated their demand for immediate signing of the unchanged regulations and then walked and rolled out of the office. Television cameras captured the events on film. The following morning, on April 5, hundreds of disability activists gathered at the Capitol building, where they publicly declared their demand for immediate signing of the regulations. Later in the afternoon, they marched several blocks from the Capitol to the HEW building. Simultaneously, activists staged demonstrations at regional offices in Atlanta, Boston, Chicago, Dallas, Denver, Philadelphia, New York, San Francisco, and Seattle.

National Council on Disability: Equality of Opportunity -- The Making of the Americans with Disabilities Act

The April 5th demonstrations brought out hundreds of activists across the country who staged sit-ins in DHEW offices, as well as many others demonstrating in support of them. At the end of the day, after making their point, most withdrew from the federal offices.

Most.

However, demonstrators at the HEW office in San Francisco, and at HEW headquarters in Washington, DC, continued to hold their positions, and the Carter Administration did not want the embarrassment of arresting "the deaf, the blind, and the crippled." There were conversations going on between ACCD leaders and the HEW. The demonstrators remained in the two offices until April 28, when Califano finally signed the Section 504 regulations.

Ragged Edge Online: Signing the Section 504 rules

The unpalatable prospect of arresting the disabled demonstrators -- or alternatively, the potentially explosive situation of 3,000 disabled individuals who were scheduled to come to Washington in just under four weeks for a White House Conference on Handicapped Individuals joining the sit-in at the DHEW offices instead of attending the Presidential conference -- eventually spurred the administration to act. The long-delayed regulations were at last signed and the full provisions of the law signed almost four years earlier were finally implemented.

---------------------------------------

The Rehabilitation Act of 1973 proved to be -- as it was intended -- a watershed event in the evolution of disabled rights. Providing both a laboratory to develop effective tools and programs and an avenue for "working out the kinks", it laid the groundwork that, thirteen years after the final victory in 1977, expanded most of the provisions and protections of the act beyond the government sector to all facilities serving the public, regardless of whether they received federal funds or not, via the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990. The Americans with Disabilities Act was the culmination of a long process of often incremental improvement in the rights and treatment of the disabled that came about through the regulatory action of our government.

But sometimes, you have to make them do it.

----------------------------------------

And that, dear Kossacks, is where regulation comes from -- not from bored bureaucrats sitting in an office in Washington trying to think up ways to make life miserable and expensive for some innocent and unsuspecting businessman, but from real human suffering and tragedy brought about, all too often, by people who shirk what should be obvious responsibilities. We have to force them, through regulation, to behave as they should have been behaving all along. That's how regulation came to be.

-----------------------------------------

----------------------------------------

Previous installments of How Regulation came to be:

---------------------------------------