Adapted from a diary written in 2008.

As we remember and celebrate the life of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. on the 83rd anniversary of his birth, events include a celebration of his legacy of environmental and social justice. This diary remembers those dimensions of his work as they relate to his final campaign.

One of the many corrosive effects of racial segregation in the United States is the unequal exposure to wastes and hazardous substances faced by people of color in both urban and rural areas across the nation. Consciousness of environmental racism grew in the 1980s, after a variety of incidents (including the siting of hazardous waste sites in Houston and the 1982 protests of a polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB) dump in Warren County, North Carolina that marked the first time Americans had been arrested for protesting a landfill) became public. Parents worried about children getting sick. Cancer rates in affected areas skyrocketed. In the years after the federal government evacuated the neighborhoods surrounding the Love Canal chemical dump site in upstate New York, worries grew that more communities were affected. These worries were acute in African-American communities, where similar health complaints were not unusual.

The series of events led the United Church of Christ's Commission for Racial Justice to conduct a study of hazardous waste siting in the United States. The report, issued in 1987 as Toxic Wastes and Race in the United States: A National Report on the Racial and Socio-Economic Characteristics of Communities with Hazardous Waste Sites, concluded that:

-- Race proved to be the most significant among variables tested in

association with the location of commercial hazardous waste

facilities. This represented a consistent national pattern.

-- Communities with the greatest number of commercial hazardous waste

facilities had the highest composition of racial and ethnic residents.

In communities with two or more facilities or one of the nation's

five largest landfills, the average minority percentage of the

population was more than three times that of communities without

facilities (38 percent vs. 12 percent).

-- In communities with one commercial hazardous waste facility, the

average minority percentage of the population was twice the average

minority percentage of the population in communities without such

facilities (24 percent vs. 12 percent).

-- Although socio-economic status appeared to play an important role

in the location of commercial hazardous waste facilities, race still

proved to be more significant. This remained true after the study

controlled for urbanization and regional differences. Incomes and

home values were substantially lower when communities with commercial

facilities were compared to communities in the surrounding counties

without facilities.

Commission for Racial Justice, United Church of Christ, Toxic Wastes and Race in the United States: A National Report on the Racial and Socio-Economic Characteristics of Communities with Hazardous Waste Sites (New York, NY, 1987), p. xiii.

In the quarter century since the report, debate and study of environmental racism has proliferated in academic and policy circles, as have organization and protests to remediate environmental inequities. The organized response to environmental racism has grown in the last quarter of a century, fighting a battle that is far from over, yet doing so in ways that will not be easily dismissed, ignored, or dissolved.

All of this happened many years after Martin Luther King died in Memphis more than 40 years ago. Yet Dr. King's work shaped today's struggle for environmental justice; indeed, the last work he ever did was in order to improve the lives of African-Americans in Memphis affected by waste -- the city's sanitation workers.

The event that triggered the strike took place on February 1, 1968. Two workers, Echol Cole and Robert Walker, were on a garbage truck. By "on" I mean they were riding on the back of the truck as was procedure in Memphis's Department of Public Works. In a pouring rain, the two men tried to take cover as best they could by climbing onto a perch between a hydraulic ram used to compact the garbage and the inner wall of the truck. Somewhere along the drive, the ram activated, crushing the two men to death. One had tried to escape, but the mechanism caught his raincoat and pulled him back to his death.

The deaths angered union organizer T.O. Jones, who called them "a disgrace and a sin." In the days ahead, workers, local clergy such as Robert Lawson, and union activists mobilized to demand safer work conditions, better pay, and the right of union representation. When Echol Cole and Robert Walker died, a movement was born.

In reality, though, those men's deaths merely were the culmination of decades of subjugation, made worse by recent worsening of treatment by the mayor's office. The subjugation was not simply of working people, but of African Americans. In Memphis, African Americans were the sanitation department -- more than 1,300 black workers, some who grew up in the city, others who had left the crushing poverty of the cotton fields in Mississippi, picked up the garbage and yard wastes of all Memphians.

Effective sanitation services are vital to all cities, but the sanitation department in Memphis has a special place in that city's history. Memphis, a hot humid city, suffered from epidemic diseases as it grew in the mid-nineteenth century. Yellow fever almost wiped the city off the map in the 1870s; after thousands died, more fled, and almost every person who stayed became infected in 1878, the state of Tennessee repealed the city's charter. The creation of the Sanitation Department under Col. George Waring in order to build modern sewers, pick up garbage, keep the streets clean and reduce the presence of infectious materials in the community as much as possible literally saved Memphis in the 1880s. (Waring later revolutionized New York City's streets and sanitation department. His work protected hundreds of thousands of lives and established the model of modern municipal sanitation in the United States that we enjoy today, but that is a story for another time.)

Though the work was vital to the city's well-being, it was dangerous, brutal, and ill-paying. The workers were not respected by their employers, or by many of the residents and businesses who benefited from waste removal. Aside from the hazards the trucks posed, sanitation workers had to handle all sorts of materials from tree limbs to broken glass to biological wastes that could infect, poison, or injure them. In the Memphis summers, this work was conducted under temperatures regularly exceeding 90 degrees often without shade or breaks to get water. Winter conditions were such that the risk Cole and Walker took in that truck seems understandable in context. Sanitation workers could be maimed at any time, and crippling injuries were common. Once disabled on the job, the worker had little recourse for compensation and was vulnerable to a life of poverty.

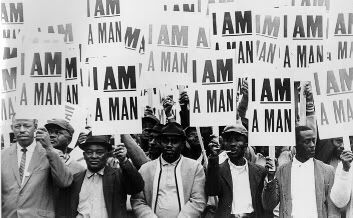

This was work white people in Memphis considered beneath them. The city found this out the hard way when it tried to recruit whites to fill the jobs during the strike. In Memphis, the necessary, vital work of keeping the neighborhoods clean was not respected by the government, nor by most of the citizens. It was dirty work, done by inferiors as far out of sight and out of mind as possible. Even as garbage piled up, the city (and in particular the staunch anti-union Mayor Henry Loeb) demeaned the workers as infantile and disrespectful, treatment that inspired the proud, defiant strike slogan: I AM A MAN!

I AM A MAN!

It needed to be shouted, it needed to be repeated on hundreds of tongues and hundreds of signs. It needed to be said over and over, because it was believed by too few. Too many in February of 1968 took for granted and demeaned the people who made their lives better. As all residents of Memphis quickly learned, the work was necessary to their quality of life, and tensions rapidly escalated just days into the standoff.

The strike quickly became a national focal point for labor activism and civil rights. Memphis's churches and local NAACP chapter saw it as the launching point to address the systemic ills of segregation plaguing the city. The American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME), caught by surprise by the sudden walkout, saw it as an opportunity to unionize municipal workers in a city that had resisted unionization. Dr. King saw the strike as an ideal forum for his Poor People's Campaign, as he had in recent months pushed the notion of economic opportunity as crucial to the realization of civil rights now that voting rights had received federal protection.

The timeline of events in the strike that lasted from February to April is too rich to recount in a diary: AFSCME has a brief chronology online, but a true appreciation of the diverse interests and activists brought together in Memphis requires a longer read. I recommend reading Michael Honey's Going Down Jericho Road to gain an appreciation of why thousands of people in Memphis and nationwide mobilized as a result of the strike. It is an engrossing and moving chronicle of why so many people were spurred to take action despite the risks.

In early 1968, Dr. King's campaigns had expanded beyond breaking the color line in the South to attempt desegregation in the urban north (including a contentious effort in Chicago in 1966) and to oppose unjust wars (speaking out against the American presence in Vietnam). His vision of equality increasingly incorporated economic issues and the rights of poor people. The criticism Dr. King received for these stances was fierce, and media coverage even among the outlets that had given sympathetic perspectives on the Civil Rights marches in the South began to echo the J. Edgar Hoover accusations that Dr. King was a Communist and subversive. Frustrated with a lack of progress on racial equality (despite the 1964 Civil Rights Act, violence in several cities between 1965 and 1967 underlined the continued racial and economic inequalities that plagued the United States), Dr. King proposed a Poor Peoples' Campaign that would ideally produce "distributive justice" in the form of government programs to abolish poverty by providing poor people enough money to pay for their own housing, education, and necessities. Far from the image of "welfare queens" that Ronald Reagan infamously demonized, these programs would allow participants to get the training required to get and keep a good job and work one's way out of poverty without being beaten down by perpetual debt while reducing the problems of crime, violence, and substance abuse that accompanied poverty. Dr. King's proposals were not unique at the time as many politicians and academics proposed similar antidotes for the ills of poverty. Yet the scorn he received for advocating these ideas helped make a sustained campaign difficult. In the winter of 1968, Dr. King made several speeches to build the campaign, yet with few organizational achievements. He was frustrated.

When Dr. King heard that Memphis's sanitation workers were walking off their jobs to protest the poor working conditions and benefits that this exclusively African-American workforce put up with while removing the wastes of the city of Memphis, he recognized a perfect setting for the Poor People's Campaign. Dr. King famously said "the movement lives or dies in Memphis."

On March 18, 1968, Dr. King came to Memphis. Speaking at the Mason Temple in front of 25,000 people (the largest indoor mass meeting of the civil rights movement) he declared:

We are tired of being at the bottom. We are tired of being trampled over by the iron feet of oppression...We are tired of having to live in dilapidated, substandard housing conditions where we don't have wall-to-wall carpets but so often we end up with wall-to-wall rats and roaches...We are tired of working our hands off and laboring every day and not even making a wage adequate to get the basic necessities of life. We are tired of our men being emasculated so that our wives and daughters have to go out and work in the white lady's kitchen leaving us unable to be with our children and give them the time and attention that they need. We are tired.

The crowd, fully into Dr. King's speech, enthusiastically agreed when he extended the strikers' plight to that of all African-American Memphians and asked them all to -- if the city did not come to terms with the strikers -- have a general work stoppage. From there, action (and tensions) in Memphis snowballed. Dr. King led a march in Memphis on March 28, 1968 that was chaotic and marred with violence. Days later, he regrouped and gave his final speech, the "I Have Been to the Mountaintop" speech in support of the strike. Dr. King broadened the focus of the strike to extend to economic equity for all Memphians as he called on the people of Memphis to boycott businesses that didn't support the strikers.

We don't have to argue with anybody. We don't have to curse and go around acting bad with our words. We don't need any bricks and bottles, we don't need any Molotov cocktails, we just need to go around to these stores, and to these massive industries in our country, and say, "God sent us by here, to say to you that you're not treating his children right. And we've come by here to ask you to make the first item on your agenda fair treatment, where God's children are concerned. Now, if you are not prepared to do that, we do have an agenda that we must follow. And our agenda calls for withdrawing economic support from you."

And so, as a result of this, we are asking you tonight, to go out and tell your neighbors not to buy Coca-Cola in Memphis. Go by and tell them not to buy Sealtest milk. Tell them not to buy—what is the other bread?—Wonder Bread. And what is the other bread company, Jesse? Tell them not to buy Hart's bread. As Jesse Jackson has said, up to now, only the garbage men have been feeling pain; now we must kind of redistribute the pain. We are choosing these companies because they haven't been fair in their hiring policies; and we are choosing them because they can begin the process of saying, they are going to support the needs and the rights of these men who are on strike. And then they can move on downtown and tell Mayor Loeb to do what is right.

He died at the Lorraine Motel the next evening. Much pain and suffered followed, in Memphis and throughout the United States. Yet even in the narrow confines of the sanitation workers' strike, his death was not in vain. The city quickly forged an agreement with the strikers that gave sanitation workers in Memphis new powers to organize and new protections on the job. A terrible price had been exacted, but Dr. King's final campaign produced progress in Memphis.

The Memphis strike also provided a roadmap for the advocacy of environmental justice. Though existing organizations such as the Sierra Club and Environmental Defense Fund did not concentrate on the effects of wastes in communities of color, the churches that spawned the Civil Rights movement did. It is no coincidence that the landmark report on toxic wastes and race came from the United Church of Christ's Commission for Racial Justice. (Its executive director was Dr. Benjamin Chavis, who would go on to head the NAACP.) The nonviolent resistance that was a staple of Dr. King's campaigns in the South was adopted in Warren County, where residents laid down in front of bulldozers en route to digging the dump. The focus on specific, localized environmental factors predated an expanded concern for environmental remediation that would see accomplishments like the asbestos remediation at Chicago's Altgeld Gardens. Much work is left to do to relieve the unequal environmental burdens on communities of color, but the attention on these problems will not soon go away.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. died more than a decade before the environmental justice movement came into being, but his work and his example were direct influences on people like the protesting residents of Warren County, on Benjamin Chavis, on environmental justice pioneer Professor Robert Bullard (read an interview with Dr. Bullard for more on his work), and on the communities across the nation and the world who recognize that racial and economic forces shaped environmental inequalities today and fight and hope to overcome these inequalities. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. may never have heard the term "environmental justice" but today as we celebrate his birthday, those of us involved in the struggle for environmental justice give thanks for his example, for his contributions, and for his hope.