Welcome to the third and final (I promise) installment of my trip last week to Vancouver, B.C., an attempt to fit a series of ecocity workshops with all kinds of sustainable design and planning concepts into a visual real life, on the ground, context.

Here's what happened so far:

Carless in Vancouver, Part 1: Boots on the Ground

Carless in Vancouver, Part 2: Going for the high-hanging fruit

On the technical end, I was there to discuss the

International Ecocity Framework and Standards (IEFS), an initiative currently being developed by

Ecocity Builders and an

international committee of expert advisers that seeks to provide an innovative vision for an ecologically-restorative human civilization as well as a

practical methodology for assessing and guiding progress towards the goal.

On the real life, human-being-traveling-to-another-city end, I was there to immerse myself in a new place, take in its sights, sounds, tricks and kicks, to enjoy the pretty face of one of the the greenest cities in North America...

but also let myself drift into Vancouver's less advertised features that give its residents an environmental footprint of almost four times the sustainable level, meaning if everyone on earth lived as Vancouverites do today, we would need three to four planets to support that level of consumption...

After four days of commuting carlessly from presentations at the waterfront convention center and workshops at BCIT's downtown and Burnaby campuses that had taken me through dense inner city blocks, sprawling suburbs, and everything in between, I was ready for the weekend grande finale: A gathering of Core IEFS Advisers in West Vancouver, and a tour of the former brownfield industrial site turned vibrant waterfront mixed-use community South False Creek neighborhood, led by BCIT Director of Sustainable Development and IEFS Core Adviser Jennie Moore.

Saturday, February 11th

Getting on a bus to analyze flows and forms that result in illumination

Cities take resources from nature. The new challenge is for cities to find ways to continuously help regenerate natural systems from which they draw resources.

- from the World Future Council's Regenerative Cities report

I got up early Saturday morning, hopped on the Canada Line and transferred downtown to the 250 Bus en route to Horseshoe Bay. The IEFS meeting was going to be at Jennie and her partner Jonn's place in West Vancouver, and I gave myself enough time for a cup of coffee on Seymore St. near the bus stop. The 250 arrived punctually, all passengers neatly lined up on the sidewalk, orderly embarking for the special 1-Zone Saturday fare. I grabbed a window seat towards the back and settled in with the blissful feeling of knowing that all I had to do for the next half hour was look out the window and enjoy the ride.

As we crossed Lions Gate Bridge to a stunning view of Burrard Inlet, two guys in their twenties sitting behind me were having a conversation that served as a reminder of how different human perception can be about the same experience, from literally inches apart.

Guy 1 to Guy 2: "I can't wait to get my car back."

Guy 1 to Guy 2: "I can't wait to get my car back."

Me (daydreaming): "I'm so happy kicking back here."

Guy 2 to Guy 1: "Yeah man. This sucks. Are you going to get that (insert fancy brand & specs) stereo? Nothing better than cranking tunes on the road."

Me (daydreaming): "Sweet silence."

Guy 1 to Guy 2: "And sitting in a comfortable car seat. This bus is crap. What's up with these uncomfortable seats. Who the hell designed them? He should be fired.

Guy 1 to Guy 2: "And sitting in a comfortable car seat. This bus is crap. What's up with these uncomfortable seats. Who the hell designed them? He should be fired.

Me (getting annoyed): These seats are just fine. You're getting a ride for two bucks in a clean vehicle, getting where you need to go without lifting a finger, great views included."

Guy 2 to Guy 1: "Yeah, why couldn't they put some upholstery on these seats? This city is run by a bunch of cheap suits."

Me (imagining slapping my forehead): "Dude, do I need to tell you what's on those upholstered BART seats?"

Guy 1 to Guy 2: "God, how I HATE public transportation!"

Me (smiling inside): "God, how I LOVE public transportation!"

When I got to Jenny and Jonn's highrise, the crew had already gathered in the community room downstairs. While not everyone on the committee had been able to make it to Vancouver, we had a nice core group of Jennie, Jonn, Kirstin Miller, Richard Register, and special guest Sebastian Moffatt, visionary building scientist, environmental planner, and co-author of

Eco2 cities: ecological cities as economic cities, who was joining us for the day to share some of his methods of measuring material flow in an organism as complex as a city.

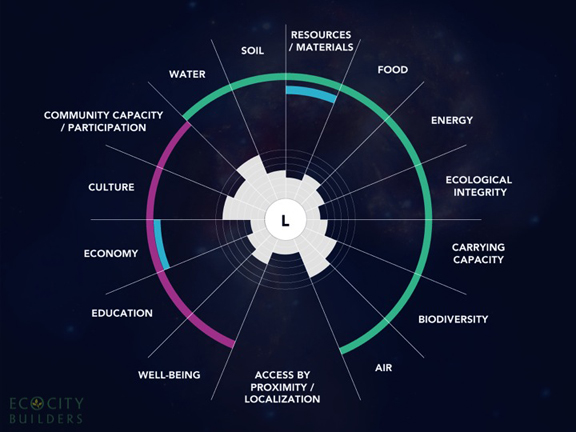

The objective of the meeting was to fine-tune some of the language on the 15 IEFS indicators by which cities can assess their progress in becoming ecocities.

Here's a way to visualize an ecocity assessment along these 15 conditions, color-coded for natural, social, and financial capital.

Our task was to refine some of the specific indicators by which these conditions can be assessed. When it comes to figuring out the Resources/Materials dimensions of a city, Sebastian has very clear ideas of how it can best be done. His material flow analysis method looks at a city's infrastructure like a living organism, with the natural and cultural environments feeding into and out of the built environment.

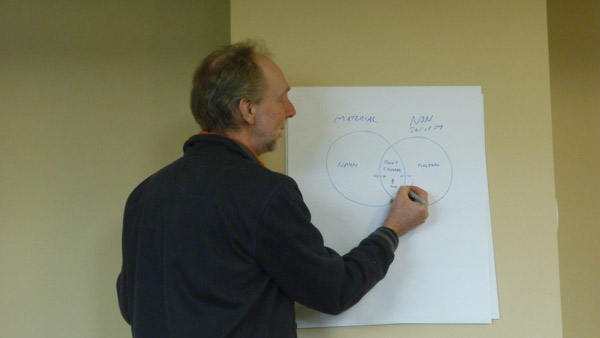

It's really all about connecting circles and understanding the whole picture...

Sebastian gave us a rundown for his preferred method of analyzing flows and forms, meta diagrams. Meta diagrams are basically visualization tools that illustrate complex information in simple and standard ways, as well as tools to calculate the flows of energy, water and materials through cities. Simply put, it's a way to track all that goes into a city, all that comes out on the other end, and what happens in between, which is what you need in order to assess a city's overall energy efficiency and ecological footprint. In fact, in most cities there currently is nobody who can describe the entire energy system and understands the whole input/output picture.

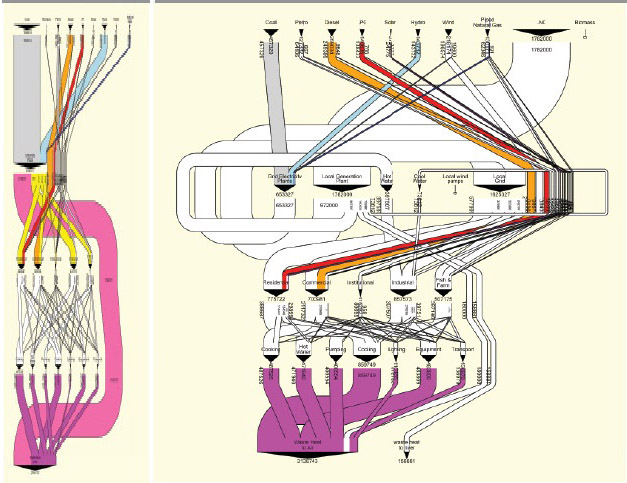

The actual visualization happens through a type of a Sankey diagram that Sebastian says is worth a thousand pie charts. If you think of it like an onion, with materials going in at the top and coming out at the bottom, then the fatter the middle the more efficiently a city is using its resources and the closer to ecocity level it is getting.

Here's an example from Eco2 cities that shows a meta diagram of the current energy system of Jinze, Shanghai on the left, and a scenario for an advanced system on the right.

The meta diagram on the right provides a scenario for an advanced system that helps reduce emissions and costs and increase local jobs and energy security. For example, a local electricity generation facility is powered by liquified natural gas and provides a majority of the electricity needs and hot and cool water for industry (cascading).

Source: Author elaboration (Sebastian Moffatt) with approximate data provided by Professor Jinsheng Li, Tongii University, Shanghai.

Pretty heady stuff, though actually quite entertaining to listen to someone with as much heart and soul as Sebastian. There were several times when Richard and Sebastian were immersed in an animated tango of ideas that reminded me just how blessed I was to be a fly on the wall with these two pioneers. I really love this shot I took of them as we were heading to lunch.

Sebastian & Co...

The whole crew having a great old time...

After lunch we went through a few more of the IEFS Indicators, refining, tweaking, and streamlining language and definitions, also with an eye toward the Road to Rio.

When I finally got on the bus back to Vancouver Island, the sun had already set and I was ready to get back to my abode to get some well-deserved rest, but travel has a way of thwarting your plans in mysterious way. I'm not sure why I decided to walk across downtown to the Yaletown station instead of connecting directly to the Canada Line at City Centre, but sometimes you just have to follow your intuition into the light.

I had accidentally discovered Illuminate Yaletown, a street party featuring amazing light installations from local artists.

From flickering ice sculptures...

to fiery dance parties...

from futuristic digital projections...

to good old fashioned pedaling for the light...

it was a perfect in-the-body ending to an in-the-head day. It brought me back to my basic understanding of what it is about cities that makes them such fertile grounds for the kinds of ideas and interactions that will help humanity transition into a world with fewer fossil fuels: their capacity to bring us closer to each other, to make us marvel at the small things in life, and just perhaps, to get a little closer to each other.

Sunday, February 12th

In search of a model sustainable community

Until we have ecocities we won't even know the potential they have.

- Richard Register

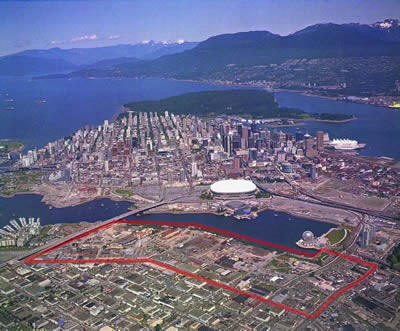

I think we all felt pretty satiated with good theory nutrients, so when Jennie offered to give us a Sunday tour of the neighborhoods at the southern end of

False Creek, the inlet that separates downtown Vancouver from the rest of the city, spanning Burrard Street Bridge on its western end,

all the way east to Science World,

none of us complained.

But lest you think this was going to simply be an act of gratuitous tourism, worry not. The False Creek villages are living breathing laboratories of some of the most progressive and visionary urban planning ideas put to the test in the last 40 or so years, and we were going to learn quite a bit about the history of this long and illustrious process to transform the former industrial heartland of Vancouver into the kind of walkable, resilient, human-scale communities that could thrive for generations.

The South False Creek developments really happened in two stages. The original South False Creek Village, conceived and built in the 1970s, runs from Cambie Street Bridge west to Granville Street Bridge. The newer Southeast False Creek Village, first outlined in the 1990s and completed in time to serve as the 2010 Olympic Village, runs from Cambie Street Bridge east to Science World.

Left: Aerial of South False Creek Village; right: Aerial of Southeast False Creek Village. Photo credits: City of Vancouver

We met at the Sandbar Restaurant on Granville Island for lunch, which was just a short bus ride on the 50 for me. Granville Island is another former industrial manufacturing area that has been turned into a lively commercial district with galleries, artist studios, a marina, and a public market...

that is bustling with hundreds of stalls with local Vancouver craft and culinary offerings.

What makes this place really cool and attractive is that they've kept a lot of the buildings like machine shops and concrete plants from the island's industrial heyday intact,

an aesthetic accent that gets completely neutralized by the sheer number of cars and horrendous traffic...

I really don't understand why they allow cars other than delivery vehicles on this beautiful 35 acre patch. It's the kind of place that would be perfectly suited for a pedestrian zone, with its narrow streets and layout, and just a short walk across the bridge (or electric shuttle ride?) to get there. Having an unlimited number of cars on this small island sucks for everyone, whether you're a pedestrian constantly trying to dodge cars and breathing in exhaust or a driver stuck in traffic. You really have to be a bird to enjoy that kind of mayhem...

How different a car-free urban environment feels became quickly apparent when we crossed into South False Creek Village that starts with the community center and playground at the eastern end of Granville Island.

And that was just the beginning. From there on the next mile or so was along pedestrian and bicycle paths that weave along the waterfront and all through the South False Creek neighborhood.

Richard looked like a happy walker...

It's not that people who live here don't have any cars at all, but as Jennie explained, the whole idea behind the design was to put car space much lower on the priority totem pole than people space. Every now and then she would point out a "parkade" — one of the existing parking areas relegated to a few tucked away spots around the village where residents can park their cars. These parkades not only keep the aesthetic focus on green space and people space, but by being spread out in a few centralized locations around the village they make the act of driving a little less convenient and impulsive, causing people to drive less and perhaps even not own a car at all.

The other thing that immediately jumps out here is the architecture of the buildings...

and the context within which the buildings occur...

Remember, this was conceived and built in the 1970s, so some of the looks may seem a bit dated, but notice how carefully this was designed to avoid one approach from dominating the whole development. Adding interesting twists on multiple-unit buildings, each unit, regardless of its value, has windows on either side of the east-west or north-south axes to ensure adequate access to light, with winding paths and roads to create breathing space in between. Even for today this kind of layout that mimics the type of historical spider web growth of European cities is still pretty unusual, but imagine these ideas not only being espoused but implemented in the 70s.

Jennie told us a little bit about the planners, architects and engineers behind South False Creek Village, a group of intrepid pioneers who at the time worked for a major Vancouver architecture firm named Thompson, Berwick, Pratt and Partners (TBP&P). Not only did they have the know-how to draw up such an ambitious blueprint but they provided the strategic connection between the two worlds of government and citizens. Too often, these kinds of ideas either never make it past the drafting stage, or if they do, they turn into developments that look good on paper but ultimately nobody wants to live in. In the case of South False Creek Village, it's still popular 40 years later, among its domesticated residents...

as well as the wild ones...

Inspired by legendary writer, urban planner and activist Jane Jacobs' philosophy of a mindful development of cities that empowers its citizens to trust their common sense and be engaged in the process of shaping their place, the young TBP&P design team drew up the plan for this new kind of urban community. A fascinating article entitled How to Grow a City — South False Creek’s Forgotten Visionaries by Cory Verbauwhede, whose father Jos had been part of the TBP&P team, describes at great length the thinking and process that went into creating this socially-conscious and carefully designed community.

Here's a nice passage from the article about how they were really trying to reach residents from across the social spectrum with their design, making it affordable, inclusive, and beautiful, something that would be attractive to old and young, low and middle income folks, and all ethnic backgrounds.

It was hoped that this kind of inclusive planning would not only make the risky venture of socially mixed housing work, but also encourage a feeling of community and neighbourliness. The enclaves would give residents a sense of ownership of the area surrounding their homes, and families were to feel comfortable letting youth play in the communal open area separated as it was from the outside world by an intricate set of pathways and covered passages.

The challenge of keeping sustainable urban living available to all segments of society and not just as a feelgood status symbol of the well-off is an ongoing one, and especially some of the new downtown Vancouver

eco-density developments seem to be straying far from the original South False Creek vision.

Jennie describes it best, along with a photo:

Here is a photo I took of a new building being constructed in Coal Harbour. I think it really summarizes the extreme green that is happening in Vancouver, devoid of any real social equity effort (witness the downtown east-side, Canada's lowest income per capita neigbhourhood by postal code a mere five blocks away). Take a peak at the home prices - yup! Starting at $5 million. (Maybe the community that moves in will donate the Ferrari to charity and buy a community Smart Car or bus passes instead?)

photo by Jennie Moore

I also love the fact that the construction workers in the foreground who are building this thing are just getting on with the work at hand, contrasting the grit of daily life against the dream of what is to my mind the ULTIMATE example of greenwash.

We walked underneath Cambie Street Bridge past the Neighborhood Energy Utility (see

Part 2), where Jennie told us about the struggles between the idea people and the forces of the status quo, or as Cory Verbauwhede calls it, "the hippies and the suits." As we entered Southeast False Creek, she pointed out how the Olympic Village, celebrated around the world for its cutting edge sustainable design, would never have happened in its current form without the dedicated efforts of a handful of citizen activists. In wise anticipation of the problems we would be facing worldwide, they helped to draft the first municipal blueprint for responding to global warming with everything from bicycle infrastructure to energy-efficient land use back in 1990,

The Clouds of Change report.

Conceived and put together by a whole team of visionaries that included University of British Columbia Professor William Rees and former City Council member Gordon Price, this was a body of work that gave rise to the City of Vancouver's mandate to incorporate sustainability into all City operations as a "way of doing business." By the time the Winter Games were being awarded, the foundation had long been laid for the most energy-efficient Olympic Village in history that is now one of the greenest communities in the world.

The jury on whether Southeast False Creek will be a success is still out. Strolling through the village center one definitely feels a pulse, but it is also clear that this is a work in progress.

The 2010 Olympic Games seem but one stage in a long and sometimes arduous process of creating the kind of urban living that is easy on the earth, economically viable, and fun, attractive and attainable for a wide range of people. The South False Creek area, and to some extent the whole City of Vancouver, is ultimately an experiment in the age-old challenge to find the right balance between our human needs and the laws of nature that do not allow us to extract more from this planet in a sustained way than we replenish.

To borrow from Winston Churchill, the way we shape our environment will determine how our environment shapes us.

o~O~o~O~o~O~o~O~o~O

crossposted at A World of Words

Carless in Vancouver, Part 1: Boots on the Ground

Carless in Vancouver, Part 2: Going for the high-hanging fruit