In the past, the relative sea level has been several feet higher than it is now, even without Anthropogenic Global Warming (AGW). It is possible that the current level of the sea is lower than it should be. We’re not sure. One thing we do know is that sea levels will go up as glacial ice melts. Notably, over the last few years, ice has been melting at a higher rate than expected. Estimates of sea level rise over coming decades have generally been modest, but if we are under-estimating the rate of ice melt, then we must also be under-estimating the rate of sea level rise.

Before considering this any further, however, I’d like to discuss something related, less urgent, but perhaps more interesting to some. My own interest in climate change began before concern over AGW was as clearly defined as it is now, and had to do with historical sea level rise. I was doing prehistoric archaeology in a coastal region, in New England. That region was first occupied by humans at the end of the last “Ice Age” when sea levels were very low because so much water was trapped in the enormous continental glaciers that covered much of North America and Eurasia. In northern New England, there was so much ice, and it was so heavy, that during the maximum glacial the land was depressed by hundreds of feet. In southern New England (and elsewhere) the land was not depressed…in some places it was actually elevated because of bulging that occurs when the Earth’s crust nearby is depressed…and much more land was exposed because of the lower sea levels. Sea levels were so low that almost everywhere in the world the very margin of the continental land masses was exposed, with the deep sea floor being just off shore. When the glaciers melted, sea level rose very quickly for a few thousand years, then the rate of sea level rise slowed but was probably still an important factor in the formation of coastal features such as barrier islands, and then eventually, about 3,000 years ago, the rate of sea level rise slowed to a crawl. However, that earlier rise in sea level is still having an effect on the morphology of modern coast lines.

Imagine yourself as a hunter gatherer living on Australia’s Nullibar Plain sometime around 14,000 years ago. This vast very flat region of southern Australia is edged on its southern border by a cliff below which the plain extends a great distance beneath the ocean. During the last Ice Age, with so much water trapped in glaciers, sea levels were much lower and this part of the Plain was dry land. So imagine you are a hunter gatherer living there, on the coast, exploiting the local seafood. Tiring of cockles and clams, you leave your sea-side camp to head inland for a bout of kangaroo hunting. You get up early in the morning and walk several kilometers north, away from the sea. You eat a Kangaroo or two, make camp, and go to sleep. The next morning, when you wake up, the sea has caught up to you. The sea is rising at the same rate that you are walking, or a bit slower. Or, on some days, a bit faster.

Is this possible? No one really knows how fast the sea transgressed broad flat areas like the Nullibar Plain during these early days of glacial retreat, but if you do the math, there may well have been days like that. There was a period of time, around 14,000 years ago, when sea levels globally rose about 30 meters in about 1,000 years. During this period is a time referred to as “Meltwater Pulse 1A” during which it is possible that sea levels rose 20 meters in as little as 200 years. If that was gradual and steady, the sea would rise between 3 and 10 centimeters per year on average, depending on the year. But this could have been in fits and starts. For instance, ice would almost certainly have been melting a lot more for certain months of the year than others, and although the dispersal of water across the globe would smooth that out to some extent, there would probably be seasonal oscillation, concentrating the rate of rise. A 3 cm per year rise may have happened mainly during four of that year’s months. Perhaps for several years the melting would be minimal, or glaciers might even be re-growing briefly. During the Meltwater Pulse it is quite possible that a) half the rise in sea level occurred in one fourth of the period in question (i.e., 10 meters in 50 years) and during this period, more occurred during certain months than others. How does that play out on a day-by-day basis? We have no idea. If there were surges of 10 or 20 centimeters in a day, that might have left geological evidence, but not of the kind we would be likely to see today, for various reasons. A nearly perfectly flat plain with an edge at the sea could have experienced unexpected flooding of many kilometers in a day or two with spring tided and storms. Certainly, observant people living on flat coastal plains would have noticed the movement of the strandline on a multi-year or a generational basis.

I have had this experience myself, in relation to the coastal landscape still catching up to historical sea level rise. When I was a 14 year old amateur radio buff, I was quite impressed with the footings, spaced about 30 meters apart, of Marconi’s old radio antenna on Cape Cod, built in 1902. By the time I was 30, that entire structure and all the land beneath it had been eaten by the sea, which has been busy transgressing the Cape. Well over 30 meters of land had retreated along the Outer Cape’s sea cliff. This was not due to sea level rise that happened during those years. This is the long term result of sea level rise that had happened previously, over the last few thousand years. You see, first, the sea goes up, then it goes across, with that transgressive erosional process being very variable in speed. Cape Cod is probably still a “cape” (I’ve not been there in a long time) but starting in the late 20th century, the outer reach of the cape started to become an island during storm-level tides. Eventually, there will be Cape Cod and Cod Island (or whatever they name it) and then, just a truncated Cape Cod and people will wonder what life in P-Town must have been like before it was engulfed by the sea. But again, all that is from the sea level rise that has happened already, not having much to do at all with Anthropogenic Global Warming.

When the sea rises it cuts into the land horizontally, with the material removed by that erosional process being reformed into a mostly sandy sheet below low tide, or into barrier islands or other features. (Finer sediments are washed out to sea.)

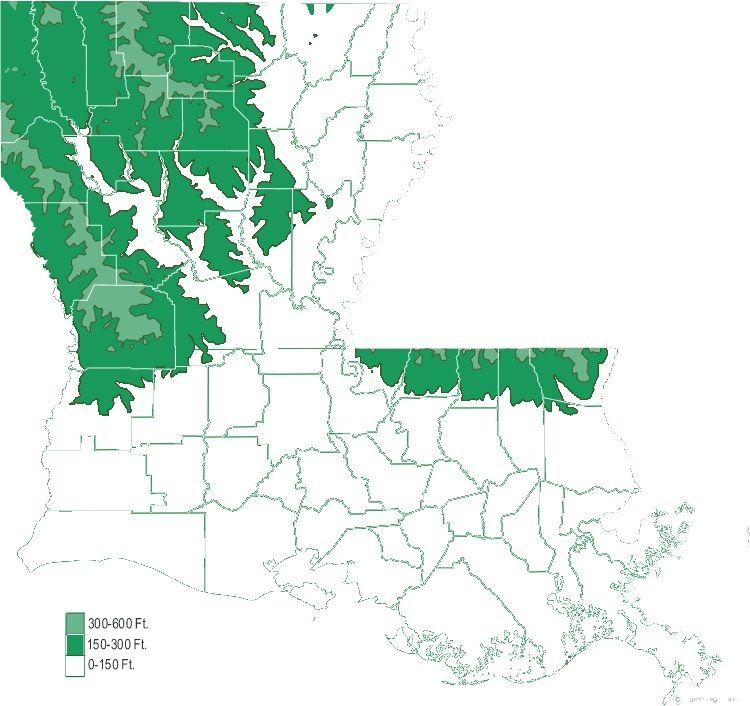

So, when we add 3 centimeters here and 2 centimeters there, vertically, we are adding an unknown but potentially quite large amount to the horizontal transgression. That has to be kept in mind when thinking about future sea level. If you guess that there will be a one meter sea level rise over several decades, you can’t just look for the topographic line one meter above the current sea level and assume the sea will rise to that point. The edge of the land at the sea is almost never a gradual uninterrupted slope. It is usually a wall or cliff of some sort, indicating an active erosional process. Think of it this way. In the absence of any sea level rise at all, if there was no uplift (as in mountain building) or volcanic activity, the sea would eventually eat all of the continents, eroding every single thing down to sea level. That would take a very long time, but it is in fact happening right now. With sea level rise, this horizontal erosional process is quickened, in some places quite a bit. Among the worst-case scenario models even if we limit AGW now, sea level rise may be as much as 6 meters (I’ll explain where this worst-case number comes from in a moment). If you look at a map of the southern US, you can estimate how far inland the sea might extend if it was 6 meters (close to 20 feet) higher. Only the southern most parishes of Louisiana have much land that is 20 feet or less above sea level at the gulf coast. But the sea rising across this landscape would produce an erosional front. If you wanted to draw a line seaward of which you’d want to avoid long term investment in land, you would probably want to look at the 50 to 70 meter (150 or 200 foot) level except where the bedrock is very solid. All areas of non-hard sediment at that elevation from the sea level in would be subject to very rapid erosion. Beach homes, ball parks, and camp grounds, sure. Cities and nuclear power plants, no. To give you an idea of the potential effects, here is a map of Louisiana with everything lower than 150 feet removed (Parish boundaries left intact):

That is an extreme case if we limit AGW soonish. Let’s look at an even more extreme case that could apply if it turns out that human beings have no self control at the societal level.

If all the ice stored today in the world’s major glaciers were to melt, that would raise the sea level by close to 80 meters (ca 260 feet), according to the USGS. This is probably an underestimate. Under those conditions, a straight forward displacement of land by sea in the southern US would cover most of Louisiana and much of Arkansas and surrounding low areas in other states. But if we add our 50 meter buffer to account for horizontal erosion, and add several meters for the land sinking under the weight of the ocean as it moves across the continent, the safe-estimate topographic limit for long term investment in land based projects might be something like 150 meters (about 500 feet). The sea would eventually (it might take centuries or even a couple of thousand years) extend into Missouri, Illinois and Indiana, there would be no more Florida, the broad coastal plains of Georgia, the Carolinas and Virginia would be excellent fishing grounds, and the eastern New Jersey and New York City metropolitan areas as well as Cape Cod, would be gone. In other words, if we burned all the fossil fuel we could find, and the total amount of carbon in the atmosphere went up so high that our planet would experience summer-like conditions for most of the year at the poles, and there would be no ice anywhere, ever, except maybe for brief periods, this would happen. Did you ever go to a museum in a place like Red Rock Canyon in Las Vegas or the American Museum of Natural History and see one of those maps of ancient times that says “And, this vast area was covered by a giant inland sea, the vestiges of which we find today in nearby roadcuts as limestone rock”? That Inland Sea…we would have that.

That of course is the most extreme scenario possible and it would take a long time to burn that much carbon off into the atmosphere. The last time the earth was so warm that the poles were essentially winter free, CO2 was probably over 2,000 PPM. Before recently accelerated AGW CO2 was about 300 PPM. It is now about 395 PPM. It took about 50 years to go from about 315 to 395. Taking the higher end of this rate (since we are talking mainly about worst case scenarios) we seem capable of raising the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere by about 2 PPM per year. SO, to go from 400 to 2000 (roughly) would take about 800 years. If we accelerate our use of fossil fuels a lot, that could be much less time (a few hundred years). The Founding Fathers of the United States did not know how to predict the future as well as we do today (and we’re still pretty bad at it) but if you were designing a new society now and knew that a) we can’t really stop ourselves from burning off this Carbon and b) that the society you were designing was going to last a few hundred years, then you would have to write into your constitution provisions for what happens when entire states are eradicated because of climate change, and you’d have to work out land ownership laws differently to avoid civil war when half the population needs to move.

But again, these are worst case scenarios. What I find both interesting and scary about worst case scenarios for sea level rise is that they are not at all extreme when sea level rise is viewed in the Big Picture, across Deep Time, considering Big Geology. Think of it this way. If you spent all your life living in a small scale society, like those Foragers we imagined earlier on the Nullibar Plain in Australia, and someone told you that people were capable of getting into groups thousand strong and rioting, burning and destroying everything around them, or mobbing and trampling dozens of people to death by accident at a sports game, that sort of thing, you’d think the person telling you this was crazy. It is too extreme. All the pertinent variables are outside your range of experience. It can’t happen. But it does happen, it is just something that happens rarely and must be seen to be believed. Sea level rise is like that. There were rather large islands out of sight of land that were certainly occupied by humans, that were eventually engulfed by the rising oceans. This is as unimaginable as it is indubitably true.

Now, why is a 4–6 meter rise in sea level even if we kinda-sorta manage AGW over the next several decades possible? Because that is the level of the sea at previous times when we had about the same amount of CO2 in the atmosphere as we have now, or actually, less.

During the last interglacial, the Eemian, the sea was about 6 meters higher than it is today. If the amount of ice that typically seems to melt during an interglacial ever, plus a little more to account for global warming, were to to be added to the sea, the ocean would be several meters higher than it is now. If we do not burn another drop of fossil fuel, and compare our current CO2 amount with the Eemian, we find that the normal range of variation of sea level stand is at least a few meters, maybe even 6 meters higher, above (and maybe below) the present level. In other words, it will not necessarily take much global warming, if any, to shift the normal heat in the earth’s atmosphere and oceanic systems around to cause a lot of ice to melt. Other things, presumably, could cause that. Things that were happening during the Eemian that we are pretty vague on today, that we don’t totally understand. When people talk about sea level change of “1.8 mm a year” we Paleo people laugh. Nervously. I can think of no good reason to rule out the possibility that without global warming the sea level could go up a meter or two because of large scale changes in the internal dynamics of the Earth’s atmosphere. With Anthropogenic Global Warming added to the mix, I assume the chances of a major amount of melting is not small.

Sea level rise is important independently of global warming, but it is more important in a warming world. The amount of natural variation in sea level vis-a-vis CO2 levels is probably underestimated. The amount of melting of glacial ice is probably being underestimated. In thinking about sea level rise, people tend to ignore horizontal transgression of the sea across the landscape due to erosion, and that is more important than the actual level of the ocean. The effects of sea level rise are very long term. There are important unknown variables related to sea level rise. That we don't understand the system as well as we would like does not mean that sea level rise caused by global warming is not important. It is very important.

I recommend buying some knickers.