On Tuesday, the Supreme Court heard oral arguments in two critical cases challenging a Democratic congressional gerrymander in Maryland and a Republican one in North Carolina that could determine whether the court will finally start curtailing partisan gerrymandering or give mapmakers free rein to try to rig the lines to favor their party even when the other side wins more votes. However, now that hardline Republican Justice Brett Kavanaugh has replaced conservative swing Justice Anthony Kennedy, the plaintiffs are not expected to meet with much success.

Since the 1980s, the Supreme Court has repeatedly held that partisan gerrymandering could theoretically violate the Constitution. However, it has never actually invalidated any particular map on such grounds, saying it lacks a standard to decide when to do so. Indeed, when both of these cases came before the high court last year, the conservative majority sent the North Carolina case back to the lower court by requiring the plaintiffs to prove they were harmed in each individual district and not just on a statewide basis, and it refused to expedite the Maryland case.

Both cases saw district courts strike down the maps later in 2018, with the North Carolina litigators making sure they had plaintiffs from each of the challenged districts. Consequently, if the Supreme Court upholds either of these decisions, it could establish such a standard against gerrymandering, setting a far-reaching precedent that could finally begin to place limits on the epidemic of gerrymandering that has swept the nation.

The North Carolina case consists of two lawsuits, Rucho v. League of Women Voters and Rucho v. Common Cause, that were combined for the purpose of this litigation. North Carolina Republicans had drawn a congressional gerrymander in 2016 where they explicitly said they drew 10 Republican seats and only three Democratic districts because they did not believe it was possible to draw an 11-to-two advantage. Astonishingly, state Rep. David Lewis stated unequivocally that the map was a "political gerrymander" as part of the GOP's legal strategy to stave off accusations of racial gerrymandering, which had doomed their previous map in 2016 (both maps are shown at the top of this post).

The plaintiffs here are relying primarily on the 14th Amendment's Equal Protection Clause and a variety of statistics showing that the GOP's congressional gerrymander is one of the most brutally effective gerrymanders ever constructed in the modern era, which dates back to the Supreme Court requiring that districts have equal population in a 1964 ruling called Wesberry v. Sanders. This approach is similar to one used by plaintiffs challenging Wisconsin’s GOP Assembly gerrymander, and one unfortunate downside is that it would require at least one if not two elections to take place and demonstrate how unfair the map is before a court could step in.

Meanwhile, the Maryland case, which is called Lamone v. Benisek, has the plaintiffs taking a different approach by relying strictly on the First Amendment to argue that partisan gerrymanders violate voters’ rights to freedom of association by illegally retaliating against them based on their partisan affiliation. This case was tailored toward one of Kennedy's past decisions, where he appeared more hospitable to First Amendment-based arguments, but that strategy may be doomed to failure now that he is off the bench.

So instead of relying on a statistical test to decide when gerrymandering has gone too far, the Benisek plaintiffs argue that any discriminatory partisan intent should render a district invalid. Indeed, former Gov. Martin O’Malley has explicitly admitted that Maryland Democrats drew the congressional map to achieve partisan ends. Critically, the Benisek standard wouldn’t require waiting for multiple elections to take place before the courts could intervene, unlike in the North Carolina case, which could allow mapmakers to get away with illegal gerrymanders for at least an election or two while opponents try to demonstrate unfair effects.

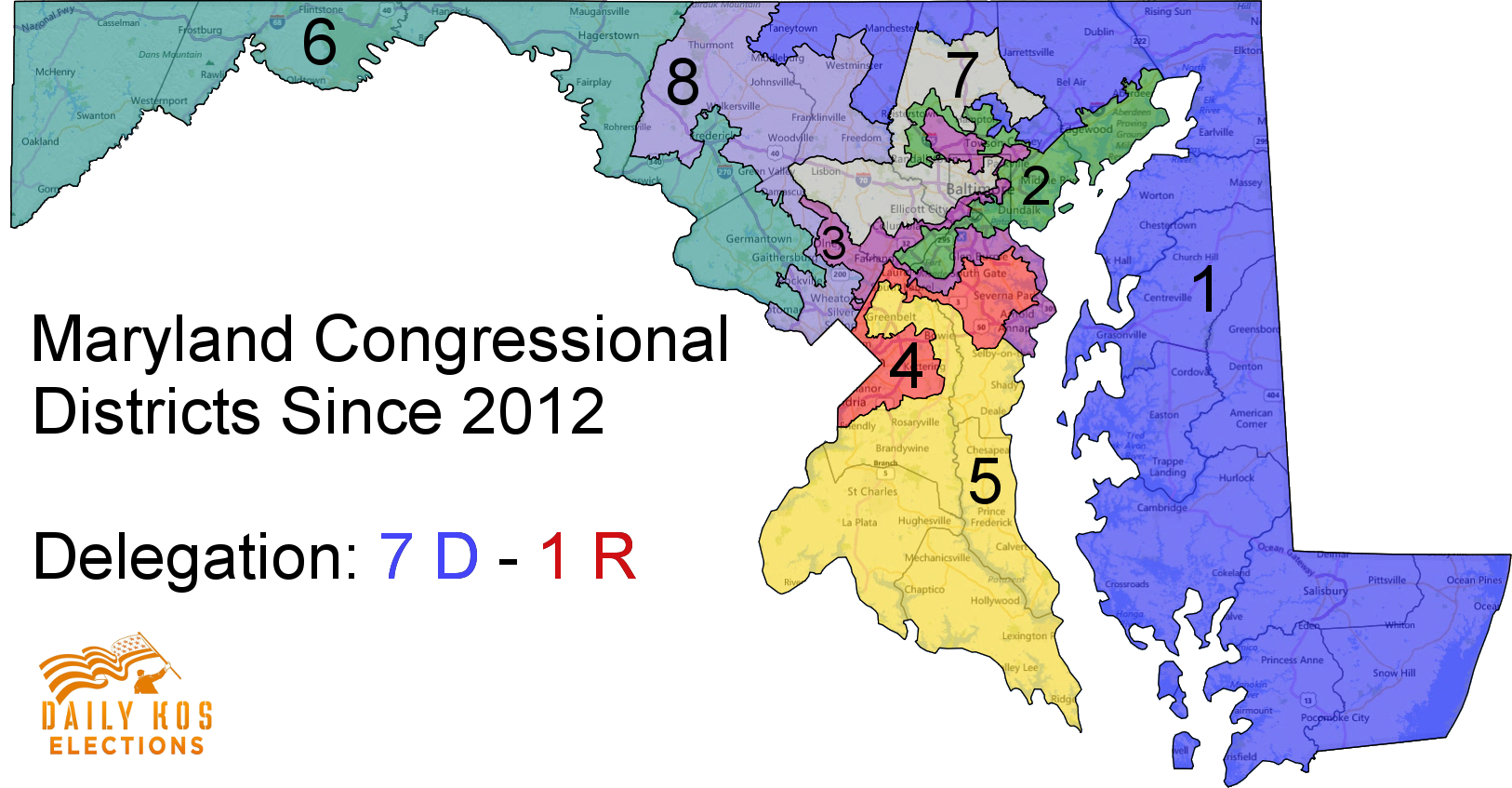

Consequently, the Benisek plaintiffs are only targeting an individual district instead of the whole map, which is shown below. They argue that Democratic lawmakers retaliated against Republican voters in the 6th Congressional District when they turned what had long been a Republican seat into one that heavily favored Democrats. (Indeed, longtime GOP Rep. Roscoe Bartlett immediately lost to Democrat John Delaney in 2012, in the first election held under the new lines.)

Not having to wait for flawed elections to take place could make it much easier to challenge gerrymanders under Benisek, but this approach isn’t without drawbacks. The North Carolina plaintiffs’ reasoning targets every district, and by using a statistical test to measure gerrymandering, legislators could be forced to redraw a large swath of the map to remedy a violation of that test. Indeed, the district court in 2018 struck down all but one of the 13 congressional districts following the Supreme Court's order to reconsider its previous ruling.

By contrast, the Benisek challengers might struggle to successfully convince a court that every flawed district in a single state is illegally gerrymandered, since the evidence may be stronger with some districts than others, even though they’re all part of the same partisan map. Furthermore, the Benisek standard could make it too difficult to challenge districts that have been gerrymandered for multiple decades’ worth of maps, rather than one that mapmakers just recently flipped from blue to red.

After Maryland's 6th District was struck down last year, Republican Gov. Larry Hogan created a bipartisan emergency commission to consider how to redraw it and to submit a proposal to the legislature. Daily Kos Elections' Stephen Wolf submitted a proposed redrawn map to Hogan's commission, which only redrew the 6th and neighboring 8th Districts, and the commission unanimously recommended that map. Wolf wrote about why he only redrew those two districts, and he also published an alternate plan that would have redrawn every gerrymandered district if the court ruling had made that possible.

Unfortunately, now that Kennedy has retired, Chief Justice John Roberts is likely to be the deciding vote, to the detriment of the plaintiffs. Even a best-case scenario would probably only leave reformers with the ability to challenge the most egregious gerrymanders, where partisan intent is as openly on display as it was in both of these cases. Such an outcome would be of limited value, though, as legislators would inevitably adapt to craft stealthier gerrymanders.

Consequently, the best ways forward for fighting gerrymandering are breaking single-party grips on state governments; using ballot initiatives; establishing progressive state supreme courts that can use state constitutional protections to ban gerrymandering in a way that's insulated from federal review; and passing national reforms at the congressional level as House Democrats just did in early March when they passed the For the People Act, which would require every state to create a nonpartisan commission for congressional redistricting.