Donald Trump’s presidential campaign has imploded after he was caught on tape bragging about committing sexual assault. Many Republican Congress members have disavowed him, while party elites like House Speaker Paul Ryan stopped defending him. This abandonment has set Trump up for a decisive loss, and Hillary Clinton currently leads by 7 points in the national polling average. Her lead could expand even further, particularly if Republican turnout drops thanks to growing disgust with Trump, and if his bogus cries of a “rigged” election discourage Republicans from voting. And on top of Clinton’s likely victory, many analysts—including Daily Kos Elections—project that Democrats are modestly favored to retake the Senate.

Very few, however, expect Democrats to win the House, despite the polls showing voters favor Democratic candidates. Why is it that the lower house, supposedly designed to be the more democratic of the two chambers, is more insulated from public opinion? There are many reasons, but one one of the most crucial is gerrymandering. Some critics contend that gerrymandering is unimportant and largely a consequence of geography—Democrats are heavily packed into dark-blue cities while Republicans are more efficiently spread out in light-red suburbs and rural areas—but this argument doesn't bear deeper scrutiny. Gerrymandering is indeed a serious problem.

In 2015, Daily Kos Elections published a series of articles where we attempted to draw entirely nonpartisan congressional maps for every state—the sort of maps you’d expect a court or a non-political redistricting commission to produce. These hypothetical maps take into account traditional nonpartisan redistricting criteria, such as respect for the Voting Rights Act, city and county integrity, communities of interest like shared culture or demographics, and geographic compactness, and they ignore things like partisanship or where incumbents live.

We then calculated the 2012 election results for president and other races for these hypothetical districts on the map shown at the top of this post (you can find a larger version here). From there, we estimated how the 2012 House elections might have turned out under these nonpartisan districts to try to measure the impact of gerrymandering.

Our conclusion was both astounding and infuriating: Gerrymandering likely cost Democrats a net of 25 seats in 2012, more than the 17 they needed to claim a majority that year, and far more than the eight they actually did gain.

With only some small exceptions, the same maps will be used again this year, and Daily Kos Elections and other analysts currently project Democratic gains of only around 10 to 20 seats, well short of the 30 the party now needs for a majority, following heavy losses in 2014. As a result, gerrymandering could once again cost Democrats a majority in 2016 even if they win more votes cast in House races nationwide than Republicans do—as they did in 2012.

How did this state of affairs come to pass? Republicans worked diligently to gain key legislative and governor’s offices ahead of the 2010 redistricting cycle, aided massively by that year’s midterm wave. The map below, which scales every congressional district to the same size, demonstrates just how successful they were:

Click here for an interactive version of this map that explains each state

Click here for an interactive version of this map that explains each state

Thanks to their success in 2010, Republicans were able to draw 55 percent of congressional districts to favor their party; Democrats did the same with just 10 percent of all seats. Making this disparity even worse, Republican gerrymanders tend to be more aggressively partisan than Democratic ones, while Democrats failed to maximize their advantage in most of the few states where they had control of redistricting, unlike Republicans.

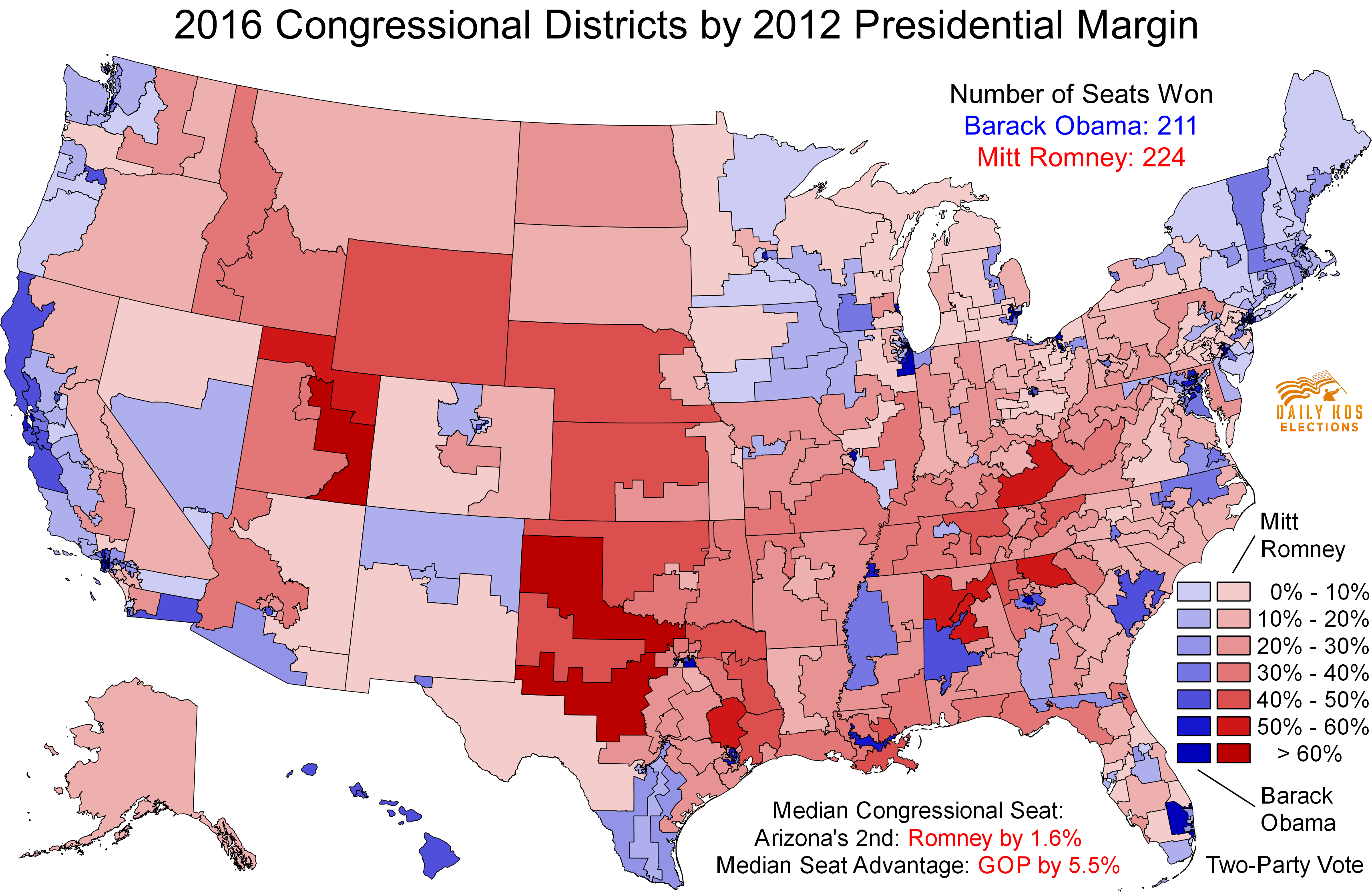

As a result, 224 congressional districts (under lines in use for 2016) voted for Mitt Romney while just 211 supported Barack Obama—even though Obama won by almost 4 percent nationwide! The map below illustrates the 2012 election outcome between the two major-party candidates, and you can see that Romney carried the vast majority of districts even in states Obama prevailed in, such as Michigan, Ohio, and Pennsylvania.

Click to enlarge

Click to enlarge

Romney’s advantage is crucial because 2012 saw the lowest rate of ticket-splitting in 92 years, and the presidential result was extremely correlated with the congressional result, as this scatterplot demonstrates:

Despite Obama winning the national popular vote by 3.9 percent, Romney carried the median district by 1.6 points—meaning half the districts voted for Romney by that margin or greater, while the other half were more Democratic (though Romney still won some of districts in the “bluer half” as well). Obama would have needed to win the national popular vote by wider a 5.5 percent just to carry a bare majority of districts, assuming they all swung toward him by the same amount. While 2016 is unlikely to experience that sort of perfectly uniform swing, it’s highly likely that Hillary Clinton would need to win by a similar margin if she is to carry a majority of these districts.

The graph below plots the distribution of districts compared to the national result, so that districts in blue gave Obama a higher share of the two-party vote than the nearly 52 percent he won nationwide, while those in red voted less Democratic. This comparison, called the Partisan Voter Index, or PVI, allows us to imagine what the result might look like if the national result were 50-50.

Doing so underscores how these districts lean distinctly Republican overall, with the most common partisanship in the range where Romney prevailed with about 57 percent of the vote or more. That’s a pretty safe level for a Republican incumbent in a normal environment, and it would likely take a wave on par with 2006 or 2008 for Democrats to win a majority.

By contrast, this is how the nonpartisan districts in the map at the top of this post break down:

Although our nonpartisan districts still exhibit a very slight Republican lean (attributable to geographic clustering of Democratic voters), it is nowhere near as prohibitive against a Democratic majority as gerrymandering is. Obama would have won 237 districts to Romney’s 198, a net increase of 28 for Obama. Instead of voting for Romney by 1.6 percent, the median seat would have favored Obama by 3.3 points. That’s just 0.6 percent less than the president’s national margin of victory, far less than the 5.5 percent disparity under the actual districts.

Mapping out the partisanship of our non-gerrymandered districts, we can see some stark changes, particularly in six large states that Obama won but where a majority of the actual districts voted for Romney. Obama would have instead carried most seats in Florida, Michigan, and Wisconsin, exactly half in Ohio, and just under a majority in Pennsylvania and Virginia. Even dark red states like Texas would have added several Obama districts, too.

Click to enlarge

Click to enlarge

While low ticket-splitting makes the presidential result a very strong factor in predicting congressional results, we weighed several factors when determining whether our new maps would have caused the parties to gain or lose seats in 2012. Although the power of incumbency has declined in recent decades, it’s still almost always a valuable asset. Likewise, some districts still tend to favor one party more downballot than their presidential result might suggest if we look at other races like governor or senator.

In total, the map atop this post shows our median estimate that Democrats would have gained a net 25 districts and thus a majority in 2012 by ending gerrymandering and substituting in nonpartisan maps for every state. We also produced both a more cautious and more optimistic estimate for a total range of a Democratic gain of 17 to 36 seats. Even the lowest number in that range was sufficient for a 218-217 Democratic majority.

Partial court victories against gerrymandering have forced the creation of new districts in Florida, North Carolina, and Virginia since the 2014 elections, and the new maps would have likely granted Democrats two extra seats by default had they been used in 2012. However, all three states are still decidedly gerrymandered to favor Republicans.

After this election, we will calculate the 2016 presidential results by both the real districts and our nonpartisan hypotheticals. We hope to run this exercise in full once again to see which specific districts might have flipped in 2016 without gerrymandering.

Of course, conditions could change in 2016. Ticket-splitting seems almost certain to rise thanks to Donald Trump’s unique candidacy. Nonetheless, unlike in past eras such as the 1970s—when voters in certain regions like the South were more likely to split their tickets than those elsewhere—we could simply see a more geographically even distribution of those voting against Trump but in favor of downballot Republicans. However, we can’t simply look at the actual House election results to see which districts Democrats might have won without gerrymandering in 2016, because campaigns themselves respond to rules changes.

Stronger candidates are less likely to run when both the chances of serving in the minority and partisan polarization are high, which is how things looked for Democrats in 2015 before Trump. Many ambitious Democrats likely didn’t want to run tough races just to have a Republican House majority out-vote them on everything.

That helped create a self-fulfilling prophecy: Conventional wisdom said Republicans couldn’t lose control, so many strong recruits didn’t run, almost guaranteeing that the House couldn’t flip. By contrast, Democrats succeeded in landing solid candidates earlier in 2015 to challenge the GOP’s Senate majority, which nearly all analysts agreed was vulnerable. If House Democrats had been as optimistic about regaining power last year as their Senate counterparts, they could have had much greater recruiting successes earlier in the cycle, before key filing and fundraising deadlines started to pass.

If Democrats gain around 15 seats in 2016 like some analysts predict, ending gerrymandering likely would have eliminated the remaining 15-seat deficit based on our 2012 assessment, particularly when you account for the detrimental effect gerrymandering itself had on 2016 Democratic recruitment. Given current polling, it seems likely that both Hillary Clinton and congressional Democrats would win a majority of districts under our nonpartisan map proposals.

Fortunately, we have reason to be optimistic that we can fight gerrymandering during the next round of redistricting after the 2020 census, but it won’t be easy. Democrats are focusing on winning gubernatorial, state legislative, and state Supreme Court elections so that they can oppose gerrymanders. Nonpartisan advocacy groups have organized ballot initiatives to curtail gerrymandering or establish independent redistricting commissions. Meanwhile, if Democrats win the Senate in 2016, a Democratic president can appoint a fifth liberal Supreme Court justice who could help the court significantly curtail partisan gerrymandering.

But for now, thanks largely to gerrymandering, Democrats still face a very uphill path to a 2016 House majority. Although we rightly condemn Donald Trump for undermining democracy when he falsely claims that vote-counting is “rigged,” we must acknowledge just how systematically undemocratic our congressional elections actually are. One party should not be able to consistently lose the national popular vote yet easily retain its majority, and voters should pick their representatives, not the other way around. We simply cannot have a government of the people, by the people, and for the people until we end partisan gerrymandering.

For further details about each individual nonpartisan map and its possible impact, read the rest of our 2015 series on gerrymandering.