Another myth of good wars versus bad wars is that only the combat veterans from Vietnam suffered lasting adjustment problems; the 1945 vet came home to enjoy prosperity, satisfied with a job well done, and with few qualms about the war...But some suffered an anguish that damaged their lives and that of their families. For some, the stress continues even today.–Michael C.C. Adams, The Best War Ever: America and World War II

When do we let go of the myth that only in "bad" wars do combat veterans suffer from mental wounds? When do we let go of the idea that only weak people are affected by the overwhelming mental stress of combat? Because, as Illona's powerful diary bears witness, that myth is killing America's young veterans today. The justness or injustice of the cause does not cause PTSD; if it did, then the "Greatest Generation," fighting in the Second World War, would have had no problems, right? Yet they did. Below the fold is a look at how PSTD affected combat veterans in "the Best War Ever."

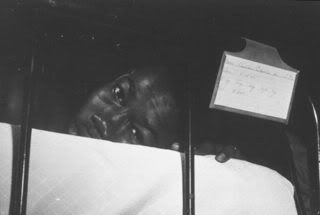

Cross-posted at Progressive Historians and Never In our Names Warning! Some disturbing images follow.

Awareness of Combat Stress

Ilona's diary struck me because, not only have I been reading Adams' book recently, I've also long been interested in the way men reacted to combat stress in World War I. I've diaried about PTSD and WW I, but perhaps it bears noting again that "shell shock" was widely documented by the time the Second World War broke out, thanks to the horrors of the previous conflict. While imperfectly understood at the time, many military physicians noted the strange sickness that afflicted many combat veterans–stuttering for some, silence for others. Panic attacks at cars starting or at fireworks. A slow retreat into depression and alcohol abuse. Suicidal thoughts and actions. All the signs were there.

But since U.S. involvement in the war was so late and so limited, perhaps it is understandable that by the time the Second World War rolled around, "shell shock" wasn't something most soldiers or their families were familiar with. Besides, large numbers of American military personnel never saw combat in WW II.

Of sixteen million military personnel, 25 percent never left the United States, and less than 50 percent of those overseas were ever in a battle zone.—Adams, p. 70

So if I've done my math correctly, only 35-40% of American troops were ever even in a combat zone. That' s still a lot, of course, but it also means that many American civilians might not actually encounter any of the men (much less the handful of women) who had been near combat. But for those who were in combat zones, they were destined to remain overseas for most of the war, with little respite or rest–a terrible formula for their mental health.

The Battlefield Reality

At induction, the Army classified men as clerical, technical, or infantry. If classified as infantry, you stayed in the infantry. There was little hope of being rotated out unless you were wounded, the war ended...or, of course, you were killed. Knowing little of this, America civilians at home tried to believe that not only was this war morally justified (which I believe it was) but it was also psychologically "clean," even when the battlefields were dirty.

But it wasn't. Try to imagine YOUR reaction to D-Day, not Hollywood's D-Day but as recorded by Ernie Pyle and recovered in interviews by Studs Terkel:

...for a mile out, the coast was littered with chattered boats, tanks, trucks, rations, packs, buttocks, thighs, torsoes, hands, heads... Hostile fire swept the beach, creating more confusion and casualties among the men, who naturally went to earth in the face of sch carnage...Timuel Black, and African-American GI, recalled that on Utah Beach on D-Day there were "young men crying for their mothers, wetting and defecting themselves, others tellin' jokes..." ...To make a shattered naval officer take his men within wading distance of the shore on D-Day, Elliott Johnson had to shove his pistol in the man's mouth and order his every movement—Adams, 101

Adding to the mental confusion were the rapidity, noise, and disjointed experience of modern warfare. Bullets and shells came from all directions, even from one's own lines (friendly fire was a problem in World War II as it still is today). In the jungles, snipers were as deadly and invisible in WW II as they were in Korea or Vietnam. In the 1980s, one of my mothers' doctoral professors mentioned that birdsong still made him tense. The reason? Japanese snipers imitated birdsong as a means of communication. 40 years later, a simple, benign walk in the woods could leave him uneasy, with a racing heart and knot of dread in his stomach.

But as bad as snipers and bullets were, the shells may have been worse. Adams notes that 85% of the casualties in the second world came from shells, bombs, and grenades, not bullets (only 10% of casualties came from these). Body armor and helmets provided little protection from many of these weapons. Incoming fire came quickly and vanished just as quickly; battles seldom had a neat climax in which the platoon knew they had "won"; rather, the fighting simply receded, leaving adrenaline, fear, and confusion in its wake. Men remained alive, some untouched, some suddenly and senselessly maimed. It all happened so fast.

Mangled Bodies, Disappeared Men

All too often, a friend or comrade was simply no longer there, save for a few pieces of what had once been a man:

At one burial, the only recognizable parts were a scalp and a rib cage...Reporter Martha Gelhorn, examining a Sherman tank that had taken a direct hit from a German 88-mm shell, saw only "plastered pieces of flesh and much blood." There were seventy-five thousand missing in action (MIAs) in World War II. Most had been blown into vapor. A WAC who assisted families coming to Europe to visit their relatives' graves said, "I don't think they know that in many cases, what remains in that grave. You'd get an arm here, a leg there."–Adams, 105

In films, death comes with nobility; cradled in his sergeant's arms, the young recruit gets to gasp out a dying message of purpose: "We did it, Pops, didn't we? We got them Nazis"(or "Japs," depending on the film).

In reality, friends and comrades–people who might have laughed with you a moment before-- were just as likely to be suddenly scattered into bits: flesh, blood, and shit spattered on the ground, the trees, one's own clothing, smelling of charred meat and burning hair. Enough left to bury? If you were lucky.

A tank officer found he was choking on bone fragments from his shattered left hand. A GI was killed by his buddy's flying head, another by the West Point ring on his captain's severed finger. ..A new phosphorus shell, developed in 1944, threw out pellets, which ignited with air to cause massive burns: one member of a forward observer team cracked up when two buddies, hit by friendly fire, flared up "like Roman Candles. "No more killing, no more killing," he sobbed.—Adams, 107

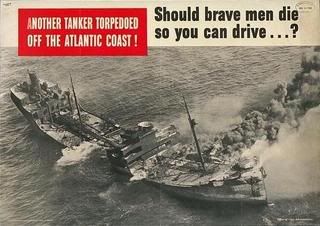

These are only the infantry stories. Although air and naval combatants fought under different conditions, they too saw horror: men burning to death in oil, slow deaths from exposure and quick ones from explosion and fire; men dying of oxygen deprivation because they had vomited into their masks, and more.

Men of all services encountered civilians caught up in the terrible war; victims of bombings, strafings, in the wrong time and place (for when war moved so quickly how could one not be in the "wrong time and place"?) Sometimes they found evidence of massacres and horrors. Worse, sometimes those horrors had been dealt by one's own gun, tank, plane, or ship. Wherever one saw death, it left scars, guilt, and mental conflict.

Mental Casualties

About 25-30 percent of WWII casualties were psychological cases; under very sever conditions that number could reach as high as 70-80 percent. In Italy, mental problems accounted for 56 percent of total casualties. On Okinawa, where fighting conditions were particularly horrific, 7,613 Americans died, 31,807 sustained physical wounds, and 26, 221 were mental casualties.—Adams, 95

There were naysayers–Patton is famous for twice hitting men in mental hospitals, calling them cowards. Some Americans could not believe or understand the depths of what this "good" war was doing to their brave men. A common charge was that men who broke down suffered from "mom-ism," being overprotected by their mothers. (Sounds a lot like those who claim today that PTSD stems from the "feminization" of the military.) But this was contradicted by the Army's own researchers:

The charge that men who had failed in combat had grown up too much under the influence of women, tied to mom's apron strings, was examined by the Stouffer team of army researchers. They found no evidence that psychiatric casualties had more protective or possessive mothers. There were, however, other clear reasons for combat stress. First, we teach children that killing is a sin. The better this lesson is learned, the more traumatizing will be the taking of life...

At some level, the solider was caught between competing and incompatible values: killing was both reprehensible and admirable. Similarly, he was the victim of conflicting loyalties: to be of service to his family, a man had to stay alive and provide for the; to be of use to his nation, he ha dot be willing to die. The tensions between those incompatibles produced nervous breakdowns.

It is not a natural thing to kill others constantly. It is not natural to be at constant risk of instant death oneself. Humans have achieved agriculture, cities, and technology in part because we have achieved long periods of peace. And even though we are animals, with an animal's ability to kill when we believe it necessary, we now kill with mechanized force, dealing instantaneous and violent deaths not seen among the rest of the animal kingdom. In short, we are neither biologically nor culturally disposed to the realities of modern warfare.

Lasting Wounds

The veterans who came back from world war two were affected both physically and mentally in ways that their families could not understand. Penicillin and MASH units allowed many to live who might have died before the war, but some families recoiled from the men with missing digits and arms, from the men so badly burned as to be unrecognizable. The fat of human flesh, like any other fat, melt sunder high temperatures. When that fat is located in the human face, it changes the features irrevocably. Someone wounded in this fashion will have the additional mental stress of dealing with other people's reactions–for the rest of his life.

Some men had mental wounds relating to specific combat situations:

Men who had faced land mines couldn't walk on grass for years afterwards. One pilot had to pull off the road when the thwacking of his tires on the concrete joints reminded him fo the sound fo flak over Germany. Another dived under his in-laws table when planes buzzed overhead.–Adams, 149

Why do we think these reactions were limited to the men of Vietnam? Maybe because in the 1940s and 1950s, it was considered culturally inappropriate for men to talk about feelings with anyone. Not a wife, not a priest, not a"shrink." A later generation was somewhat less reticent in expressing itself, so those on the outside might claim there was something "special" about Vietnam. Its men suffered because they were weak, or were moral cowards, perhaps. Or because Vietnam was a "bad" war.

Either way, many Americans politicized the suffering of Vietnam veterans, assuming it was related only to its time and place. While every war has its distinctive horrors (the experience of Agent Orange in Vietnam, for example), perhaps the Vietnam generation would have been treated more kindly had they been more aware of the suffering that their fathers, uncles and older brothers went through during the Second World War.

When does Normal Come?

But in 1945 and 1946, the United States wasn't ready to deal with its combat veterans. Good Housekeeping told wives that men would cease their "oppressive remembering" in no more than three weeks. The Army's opinion was that it would take about 2 months. No one expected it to take years. Some GIs sought and received counseling, but most simply assumed they should "get over it." Thousands could not. How long does it take to forget the stench, taste, sounds, and sight of constant death?

The divorce rate for veterans under 29 reached 1 out of 29 in late 1945, as compared to a general rate of 1 on 60. Behind those divorces lay a myriad of problems, some of which related directly to the combat experience:

Trying to repress feelings, they drank, gambled suffered paralyzing depression, and became inarticulately violent. A paratrooper's wife would "sit for hours and just hold him when he shook." Afterward, he started beating her and the children: "He became a brute." And they divorced ---–Adams, 150

How many of the wife-beating jokes that 1950s comedians told were a way of quietly acknowledging this ugly reality? How many families hushed the cries and ignored the bruises because they could not understand its caused? Reading about this, I think of the ubiquitous 1950s "cocktail hour" in rather a different light; the boozy Dean Martin fans and suave JFK-look alikes, drinking heavily because it was the only anesthetic that could wipe out the feelings of horror. Don't forget that fictional James Bond was supposed to be a vet. Throwing back martini after martini as he coldly kills for Queen and country, he never stays too long in one relationship, always doing what he must. No wonder Ian Fleming's books sold so well. He offered a powerful redemptive myth for the men struggling with all they had seen and done.

For some the horrors receded, but how many other men never really left the prison camps and the battlefields? And not just the men. The handful of women who had been under fire faced similar problems; the female PTSD victim is not some issue unique to the conflicts in Iraq. As Elizabeth Norman details in We Band of Angels, the nurses of Bataan and Corregidor who had been interned in the Philippines found themselves both hailed as heroes and shunned as "tainted" women by their communities. If Americans could not talk about why their sons came back from the front shattered, how much less could they imagine that their daughters might also have suffered from shells, starvation, and strafing? In open-air jungle "wards" and from beachhead tents that looked out over the carnage of an industrial war, the nurses had seen sights that almost no woman of her era could relate to.

If Not Now, When?

PTSD is not a sign of individual weakness, nor is it a comment on the rightness or wrongness of a war. It's not the fault of the "liberal media" for reporting on what war is actually like. It's just a fact of modern combat.

Mired in the myth of Vietnam as the "bad" war, many politicians seem to fear that if we acknowledge and deal fairly with PTSD, they are admitting fault in Iraq. That's baloney. Even if Osama had been hiding out with Saddam and we had found WMDs, even if Iraq were now humming with the fairy-tale rebuilding we were promised, we would still have men and women coming home with PTSD. Whether they die for oil or die for "democracy," in war, soldiers die. Horribly.

This war seems hopeless and pointless. But that is not the sole cause of PTSD. Even the most moral combat seemed hopeless and pointless when all that remains of your best friend is a couple of fingers. When death can rain down any instant. When birdsong is dangerous. When you've seen and smelled piles of bodies rotting in dank jungle mud. When your legs were crushed by your own tank.

Let's look at the statistics .(h/t Ilona). Let's deal with the facts. Call your representatives, of whatever party, and ask them to support legislation that would give veterans decent care. (h/t Ilona).

After 60 years, isn't it about time we stopped playing politics with PTSD?

Image information: All photographs are believed to be in the public domain of the United States because they are the works of a U.S. Army soldier or employee, taken or made during the course of the person's official duties. All photos and the poster are the work of the U.S. federal government, and therefore in the public domain. Photographs available from NARA and The Army Center for Military History. Poster from the Northwestern Library collection.