One of the few advantages of being a very old person is that I have plenty of that precious commodity, Time on my hands. I have used some of it lately to re-read Tolstoy's splendid WAR AND PEACE which I am convinced is the finest historical novel ever written. I urge anyone who is interested in the Napoleonic wars and who also has time, to read it too. It's a book full of riches--vividly drawn characters both real and imaginary, and historical events of a period of turmoil. More than this, the reader meets the great writer himself and becomes acquainted with his thoughts and ideas which are those of a true liberal and a pacifist.

For no reason that I can fathom, some people are turned off by the opening scene at Anna Palovna Sherer's soiree but it is here that the reader meets several of the principal characters---Pierre, the wily and conniving Prince Vasili, and Prince Andrew. It's easy to identify Pierre with Tolstoy.

In following chapters are met the utterly fascinating Bolkonski and Rostov families, aristocrats all. Impetuous and intuitive, Natasha Rostova is unforgettable. A slightly younger literary contemporary of Elizabeth Bennet and, although different in almost every other way, she shares Austen's heroine's elusive quality of charm. With the magic touch of an artist of words, Tolstoy brings her to breathing, pulsing life as he does with her open-handed father, Count Ilya Rostov, her brothers, Nicholas and Petya and the entire family circle. It's the same with the Bolkonskis. There are Prince Nicholas, domineering and cynical, his long-suffering daughter, Princess Mary, a saintly young woman who is at the same time human and lovable and her brother Prince Andrew, who has inherited some of his father's cynicism.

Sixty-two years ago when I read Tolstoy's panoramic masterpiece for the first time, I was so caught up and intrigued by the family life that I skipped many of the war parts. This was a bad mistake. Male members of the families are army officers and the two parts are interwoven.

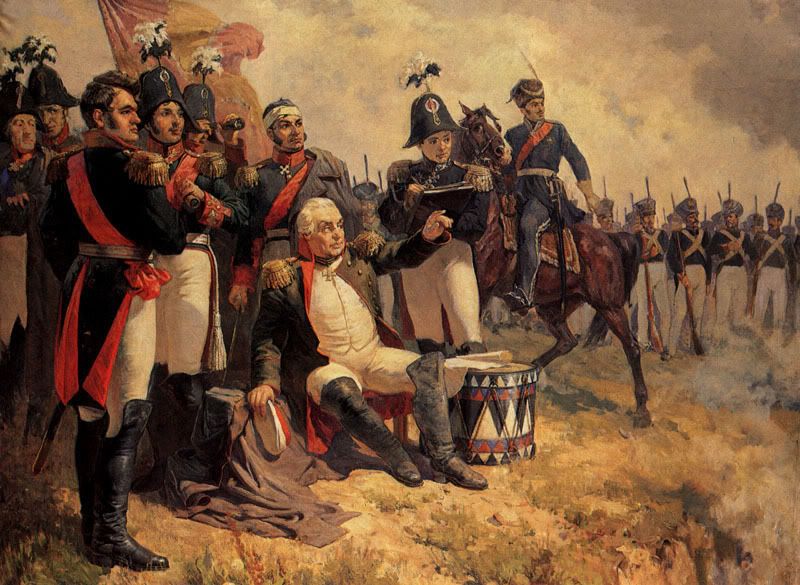

Tolstoy's description of battles, especially the decisive one at Borodino in 1812 which was the beginning of the end of Napoleon's power, is graphic and appallingly vivid. He was a strong opponent of capital punishment, which he considered calculated and deliberate murder, and the two pictures he gives of public executions are horrifying. To him the executioners, even though following orders, are murderers. The reader meets the great Russian general, Bagration and Kutuzov whom Tolstoy admires.

Kutuzov, old, fat, and one-eyed is a soldier who cares about his troops. He sees them as human beings, not cannon fodder. When Emperor Alexander I wrote complaining letters demanding battles with the fleeing enemy, the wise old warrior refused. He saw no reason to waste lives in "victories" that would only aggrandize some ambitious generals. Russia had been saved.

To me this novel is as brilliant and unique as the Great Comet of 1812, the celestial phenomenon that Pierre gazes at in the sky over Moscow. The Great Comet is long gone but we are fortunate. WAR AND PEACE is left for us to learn from and to enjoy.