Mount Brandon on the Dingle Peninsula has long been an area of pilgrimage. The mountain was originally associated with a local saint, Maolcethair. In the ninth century, the landscape became a spiritual focus of a broader cult centered on Brendan the Navigator. Brendan is known for his many missionary voyages made in a curragh (skin/leather boat) to various islands along the north European Atlantic seaboard. He probably made voyages to the Faroes, Iceland, and Greenland.

On Mount Brandon, the pilgrims follow the Saint’s Road which is approached from the sea and which passes various stone crosses, churches, and boat-shaped oratories. Thus the pilgrims re-enact many of the elements of Brendan’s voyages, and metaphorically share in the hardships he endured and the progress of his mission.

Brendan was born about 489 CE near the lakes of Killarney in County Kerry. He was baptized and educated by Bishop Erc of Kerry and studied under Saint Enda. At this time, the Irish church was organized almost exclusively into monasteries which were scattered around the island. Brendan was responsible for the foundation of several of these monasteries: at Ardfert in County Kerry, Inishdadroum in County Clare, and Annadown and Clonfert, both in County Galway. Brendan died between 570 and 593 and was buried at Clonfert.

English writer, adventurer, and historian Tim Severin writes of Brendan:

“He was one of Ireland’s most important saints, classed as a saint of the second order. He was a man who had a profound influence on the Celtic Church.”

About 800 CE, 200 years after Brendan’s death, an interesting work appears:

Navigatio Sancti Brendan Abbatis (

The Voyage of Saint Brendan the Abbot). According to this work—of which more than 100 versions have been discovered—Brendan had been living in the west of Ireland when he was visited by another Irish priest who described to him a beautiful land in the west, over the ocean, where the word of God ruled supreme. The priest told Brendan that he should go and see this world for himself. Thus, Brendan built a special boat for the voyage, making first a framework of wood and then stretching tanned oxhides over the frame for the hull. With 17 other monks, he set off on a long, hard journey. The book goes on to describe all of the marvelous things he saw on his seven-year journey and all of the new lands that he encountered.

Is the tale of Saint Brendan simply a fantasy, a figment of a storyteller’s imagination, or is it based on an actual voyage? Did Saint Brendan sail to the Americas in the sixth century? Is it actually possible to sail across the North Atlantic in a skin-covered boat known as a curragh?

The Story:

The story of Saint Brendan, like many other stories such as those in the Viking Sagas and the Christian Bible, is an example of oral tradition which has been written down. While there are many scholars who feel that oral history is not really history, many archaeologists, ethnologists, geographers, and others have found that the ancient stories provide good insights into the past. From the perspective of genetics and DNA, geneticist Bryan Sykes, in Saxons, Vikings, and Celts: The Genetic Roots of Britain and Ireland, writes:

“But in my research around the world I have more than once found that oral myths are closer to the genetic conclusions than the often ambiguous scientific evidence of archaeology.”

The Viking Sagas recounting the voyages to North America were at one time dismissed as fantasies by many historians, yet in recent years the archaeological evidence in Newfoundland provides some hard evidence supporting the Sagas. While no archaeological evidence of Saint Brendan’s voyages have been found in North America, this may someday be found.

The Navigatio recounts the adventures of the Irish monks in other places which modern readers identify as Iceland and Greenland. While there is no archaeological evidence of an Irish presence in Iceland, the Book of Icelanders written by Ari the Learned about 1133 tells of Irish monks on the island when the Norse arrived. According to his account, as Christians the monks did not wish to live near the heathen.

There is no archaeological evidence at this time of the Irish monks in Greenland, yet according to the Norse sagas when they first arrived on the island, they found the remains of human habitations built of stone, as well as stone tools and the fragments of skin boats. Some scholars, such as the American geographer Carl Sauer, feel that these skin boats and stone dwellings were likely to have been Irish rather than Eskimo.

The Curragh:

For several millennia the Irish have used a type of water craft known as a curragh. This type of craft, which is still being used today, is made using a wooden frame which is then covered with treated animal skins. The curragh can range from small boats powered only with oars (sometimes called canoes by the locals), to curraghs which have one or two masts on which to hoist sails.

Shown above is the frame for a single-masted curragh at Dingle.

The bus stop at Dingle shown above has a curragh for a roof. Tim Severin describes carrying a modern curragh:

“To carry the boat to the water’s edge, the crew crawled beneath one of the upturned curraghs, crouched so their shoulders pressed up on the thwarts, and then straightened their backs so that the curragh shot smartly into the air like a strange black beetle heaving itself up onto four pairs of legs which then marched off to the edge of the slipway.”

The Voyage:

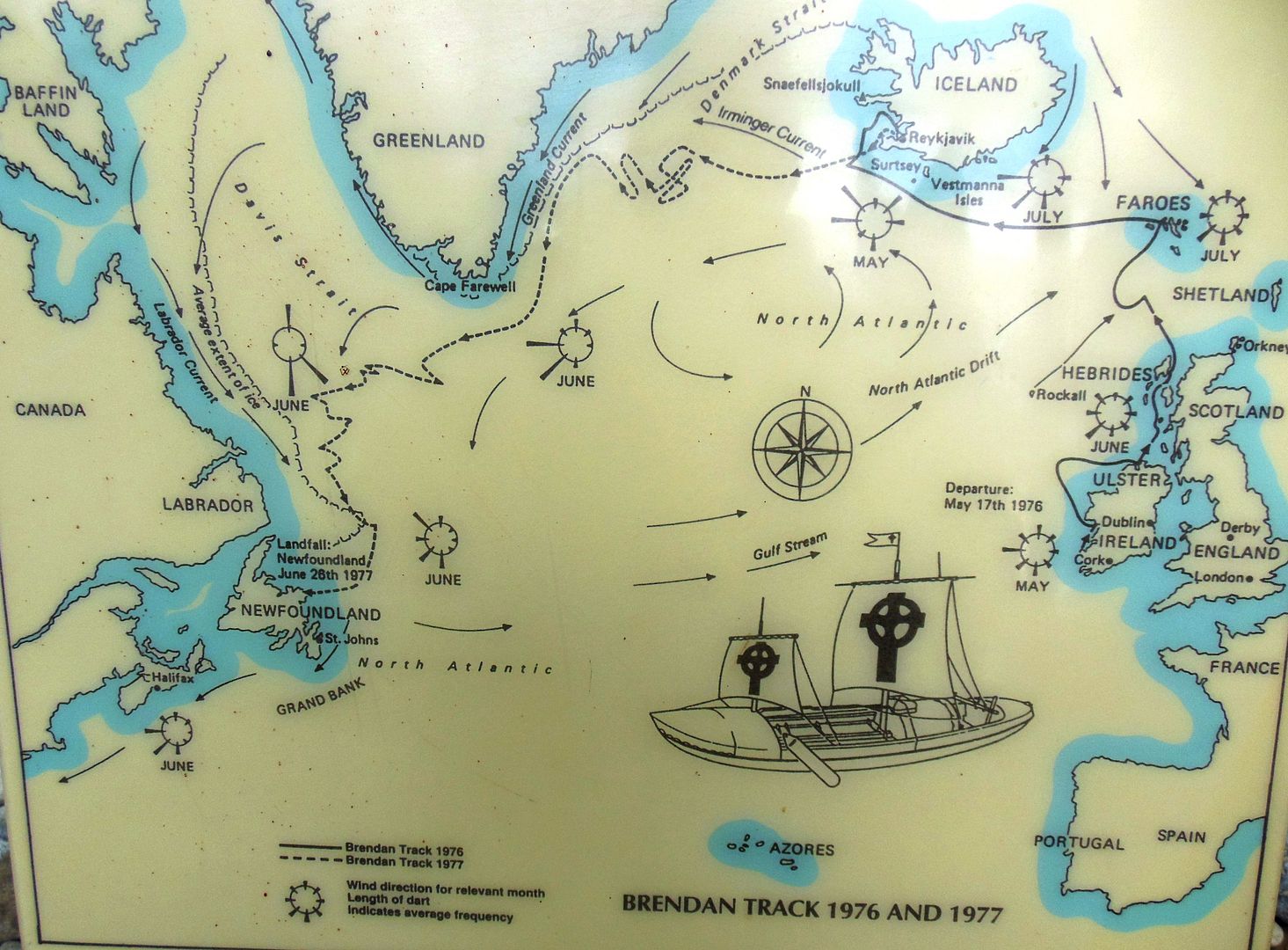

Could Saint Brendan have really made a voyage across the North Atlantic in a curragh? In the 1970s, Tim Severin set out to find out if the voyage was possible. It started with the construction of a curragh using only traditional materials (the story of the construction of the boat is a fascinating excursion into experimental archaeology). Then in 1976 and 1977, with a crew of four, he sailed it across the Atlantic, recording what he saw and comparing it with the stories in the Navagatio.

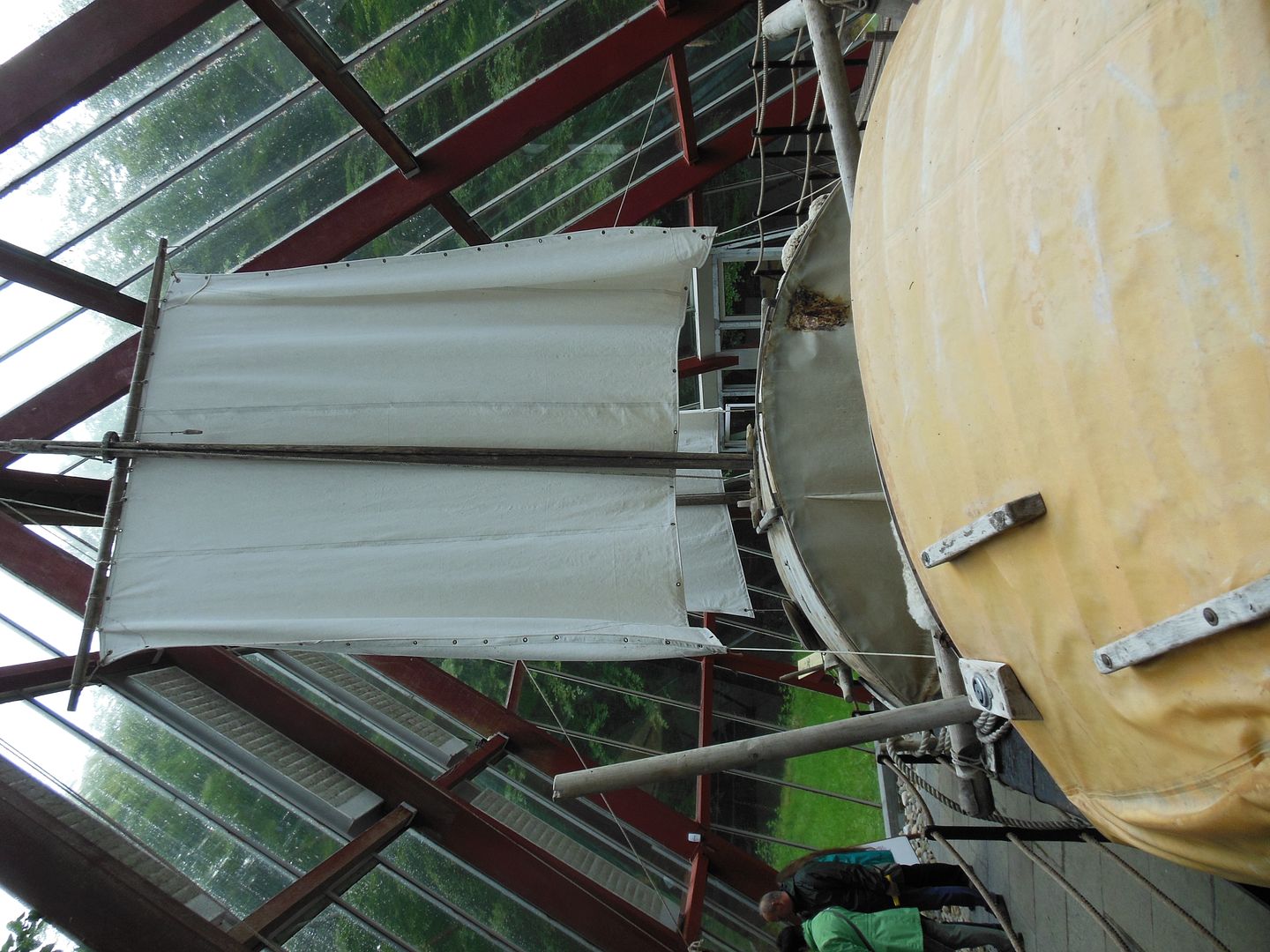

The curragh Brendan sailing the North Atlantic is shown above.

A diagram of the curragh Brendan constructed by Tim Severin is shown above.

The map of the 1976-1977 route followed by Tim Severin in trying to follow Saint Brendan is shown above.

The voyage of the curragh Brendan does not prove that Saint Brendan sailed to the Americas in the sixth century, but it does show that it would have been possible. So what did the voyage show? In the words of Tim Severin:

“At best, land archaeologists should now be encouraged to search for Irish traces in the New World, and at very least, it is difficult any longer to bury the early Christian Irish sailors into a footnote in the history books of exploration on the excuse that too little is known about them and their claims are physically impossible.”

“Thus the Brendan Voyage in 1976 and 1977 not only established the basic fact that it is entirely possible to sail from one side of the North Atlantic to the other in a skin boat built to medieval specifications, and by a rugged northern route; but it also established criteria against which to measure the original voyage tale.”

“…the flavour of the medieval text now seems wholly authentic when judged against our experiences aboard Brendan.”

The curragh

Brendan is currently on display in a special building at Craggaunowen. Shown below are photographs of this interesting craft:

The Book:

Tim Severin’s The Brendan Voyage: Across the Atlantic in a Leather Boat was published in 2005 by Gill and Macmillian in Dublin. It is a story that is about history, literature, ancient crafts, adventure, the sea, geography, and, above all, the culture and spirit of today’s Irish people.