Have you ever said or heard people say that conservatives are stupid?

Here’s a few comments I’ve seen over the past few weeks:

“In short, they’re screwy.”

“This is a big reason the GOP/T can marshal their forces in large numbers = they don't think - they just `behave’”.

“so, they're ignorant, loony, hypocritical, fake, sociopathic, pathetic, and deceitful …”

“I have a functioning brain that will not allow me to place `faith’ where `facts’ belong.”

I’m sure you won’t have to look far to find more. One of my favorites, in fact, was Stephen Colbert’s

brilliant send-up of George W. Bush at the White House Correspondents dinner in 2006:

We go straight from the gut, right sir? That's where the truth lies, right down here in the gut. Do you know you have more nerve endings in your gut than you have in your head? You can look it up. I know some of you are going to say "I did look it up, and that's not true." That's 'cause you looked it up in a book.

The message is that conservatives don’t think with their heads (or much at all).

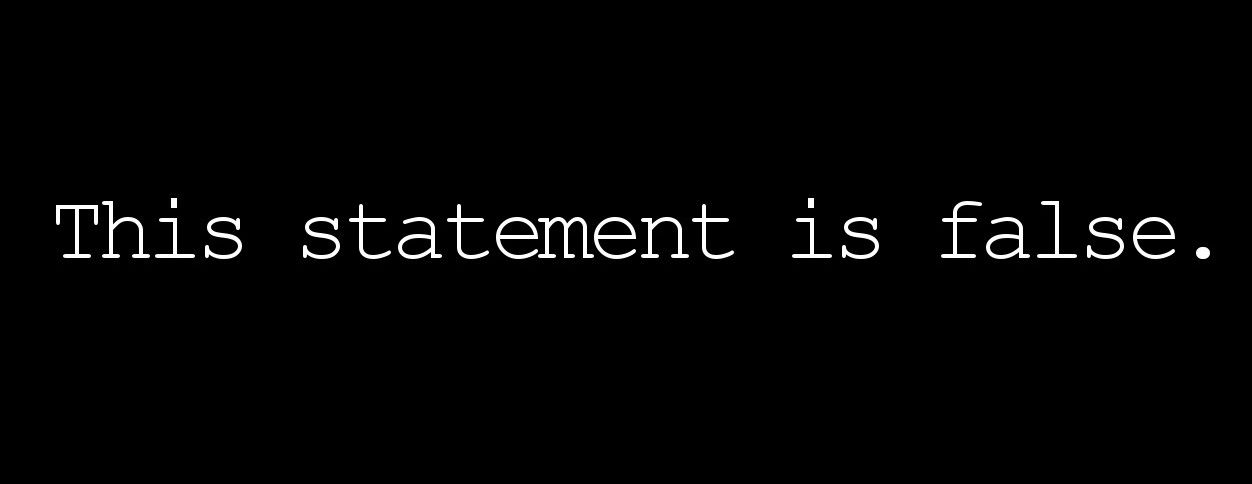

So what happens when you confront liberals with scientific evidence that refutes their own beliefs? (And WTF does Gödel's incompleteness theorem have to do with any of this?)

You probably won't believe me ("That's a joke, son." - Foghorn Leghorn).

An experiment

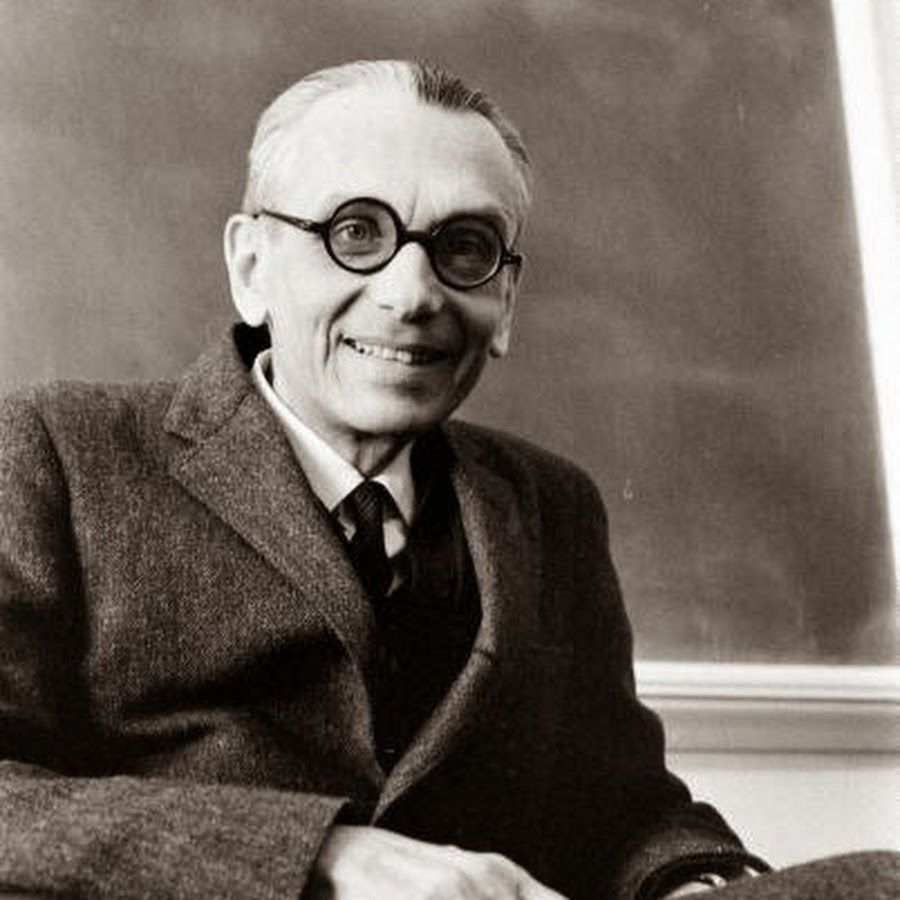

I’m going to call this the Kurt Gödel political experiment. Gödel famously proved the limitations of mathematics by finding a self-referential statement that was “outside of” a formal system of logic.

If you attempt to come up with a list of axioms sufficient to serve as the foundation for a mathematics capable of doing arithmetic, in every list there will be a statement that is true but not provable. In other words, the list of axioms cannot be both consistent and complete.

Here’s the experiment:

- The experiment is to find a liberal friend who thinks conservatives are stupid or has written something recently about conservatives being stupid.

- Do everything you can to get this person on the record as a defender of logic and the scientific method? Facts, you say. It must be facts. And science. Yes, science is the end all, be all. Science and logic.

- Then ask them what happens when science shows that people don’t make decisions based on facts or logic.

I've had this conversation numerous times. In this example, my friend S--- and I were talking about voter ID. My friend said this about someone he was talking to:

S: It exposes their extreme logical skills deficit.

I couldn’t resist:

Me: People don't make decisions based on logic. Which is an unusual fact.

S: I do, I can't help it. I have a BS meter.

The first thing people often do is get defensive. Suddenly, you’re questioning something that’s assumed “fact”.

Me: Said every person in existence. It's why it's so hard to convince people that people don't make decisions based on facts. Even though all the science we have supports it. (Just sayin' ... heheh).

Me: It's also why we get so mad with Republicans. Because fundamentally they disagree with our beliefs. And sorry ... I'll stop now

S: I don't get mad, I offer a contrast backed up, which is why L---- calls it spam. I never link to overtly liberal sites

To give you a bit more background, I’ve seen S--- become so emotionally involved in his arguments that he’s unleashed streams of profanity and had posts removed. Yet he insists here: “I don’t get mad.”

Heheh.

BTW, I’m not trying to say people shouldn't get mad. Or that there’s not valid reasons for being mad. The point is simply that politics is often about beliefs and emotion. We may want it to be about facts and logic, but facts and logic are more likely convenient tools to justify beliefs.

Me: Let me rephrase: If you believe in science, and science says that people don't make decisions based on facts ... why do you believe that people make decisions based on facts?

S: I don't. What I said about myself is something I have been aware of since I was very young. I am extremely skeptical, things just don't come off as factual to me unless they are backed up with proof. I also respect expertise. I love PubMed

Me: Well then ... show me some science that demonstrates that people make logical decisions. I will believe you when I see the science

S: I can't, because they don't. My logic deficit is I am a procrastinator

Now I've had this conversation with S--- before. This isn't the first time. The first time we nearly got into a fight in a downtown coffee shop just because I suggested that factsplaining on the Interwebs wasn't the best way to win people over.

Don't get me wrong. S--- is great at research and posting articles refuting people's viewpoints. When I have research questions, I often give S--- a yell. Research is his wheelhouse.

I also love him because he helped me come up with this self-referential experiment to explain confirmation bias. It's taken a number of conversations but I think I may have gotten through. His online conversations have changed. He doesn't seem as angry. He's starting to see others online as people and not members of some evil other group. He’s not “fact raging”. And I can see it in the conversation I shared here.

S--- isn't mad at me any more. He admits he's human. One sure sign that people are starting to understand confirmation bias is when they say "we" when talking about it instead of "them".

Our conversation has come a long way since our initial coffee shop introduction.

I share this not in any way to say S--- is wrong or Stephen Colbert is wrong but to talk about how we all have beliefs. Even if these beliefs aren't always apparent to us.

We find Stephen Colbert funny because we share the same belief about science and the value of science. We both want people to make decisions based on science and evidence.

The more we recognize this and recognize what our own beliefs are and what the beliefs of conservatives are, the easier it is to talk with them and perhaps even help them reach a different level of understanding.

Lawyers understand people tend to not make decisions based on logic and facts. Economists understand that people don’t make rational decisions. Religions understand people don't make logical decisions. Sales people understand that people don’t make purchases based on logic and facts. Why would politics be any different?

Why do we seem to believe that people make decisions based on logic and facts despite all the evidence to the contrary?

Some science

You've probably heard of confirmation bias. It’s the tendency to process information in a way that confirms your own beliefs or tendencies.

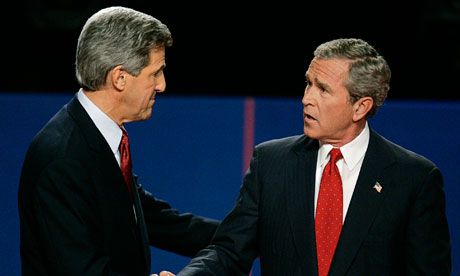

In 2006, Drew Westen conducted one of the first scientific experiments on emotion in politics. Westen used Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) to look at the areas of the brain activated when self-described Democrats or Republicans heard contradictory remarks about their favored political candidate.

The experiment:

- Recruit 30 men, 50% committed Democrats, 50% committed Republican

- Put the recruits under an MRI machine and show them quotes where a political candidate reversed a position.

- Quotes were by George W. Bush and John Kerry.

- Everyone was shown all of the quotes and also neutral quotes by a neutral person (Tom Hanks).

Republicans judged John Kerry harshly and let George W. Bush off the hook. Democrats judged George W. Bush harshly and let John Kerry slide. The areas of the brain responsible for reasoning showed little activity while drawing these conclusions. The areas of the brain controlling emotions showed increased activity as compared to the subject’s responses to politically neutral statements.

After partisans had ignored rational information and come to completely biased conclusions not only did negative emotion circuits (disgust, sadness, and so on) turn off, but areas of the brain involved in reward were triggered.

In other words, partisans responded in many ways as if they personally were being attacked and were rewarded when they defended their group. Westen’s research shows that when facts are viewed as an attack on the individual (or group), individuals respond by rationalizing the behavior of the group member and judging the behavior of the non-group member.

Often we talk about confirmation bias as something that the “other side” side does. Yet when it comes to our own belief that people should be convinced by science and facts, we defend it as strongly as any conservative. Or conversely, we simply look down on those who we think can’t see “the truth”.

Brendan Nyhan and Jason Reifler have also conducted research into whether misperceptions can be corrected. In several studies, they have actually found evidence of a “backfire effect” in which refutations actually increase the emotional misperception.

The first experiment they conducted showed participants fake newspaper articles where the claim that that Saddam Hussein possessed weapons of mass destruction was first suggested (in a real-life 2004 quote):

There was a risk, a real risk, that Saddam Hussein would pass weapons or materials or information to terrorist networks, and in the world after September the 11th, that was a risk we could not afford to take. - George W. Bush, 2005.

And then refuted (with a discussion of the findings of the 2004 CIA Duelfer report):

In 2004, the Central Intelligence Agency released a report that concludes that Saddam Hussein did not possess stockpiles of illicit weapons at the time of the U.S. invasion in March 2003, nor was any program to produce them under way at the time.

What they found from the experiment was that not only were factual corrections unlikely to change minds, but in the most ideological, they even had the effect of strengthening the false belief.

Similar results occurred when conservatives were confronted with factual evidence refuting the claim that the Bush tax cuts increased government revenue. After the correction, core conservatives believed the false claim more strongly.

This is why the speaker matters. If you hear something from someone within your group, you’re much more likely to believe them than someone outside of the group. I’ve had many conversations about voter ID with liberals and have found it’s fairly easy to convince them that voter ID isn’t really that bad of an idea.

Recently, Nyhan and Reifler conducted an experiment testing strategies to communicate the factual importance of vaccinations. A representative sample of 1,759 Americans with at least one child at home was used.

Several of the messages/images tested provoked a similar backfire effect among vaccine deniers. The least effective messages, “Disease narrative” and “Disease images,” increased respondents’ likelihood that the vaccines themselves would cause disease from 7.7% to 13.8%. Digging into the data, they found that the increase occurred because of a strong backfire effect among the minority who were most distrustful of vaccines.

The takeaway Nyhan highlights:

I don’t think our results imply that they shouldn’t communicate why vaccines are a good idea. But they do suggest that we should be more careful to test the messages that we use, and to question the intuition that countering misinformation is likely to be the most effective strategy.

This bears repeating:

We should “question the intuition that countering misinformation is likely to be the most effective strategy.”

But facts and science and logic are important!

Of course they are. We should simply be as aware of their context and limitations as we are of their value.

Westen’s research simply says that partisans respond to contradictory evidence as if they personally are being attacked and that partisans are subsequently mentally rewarded when they defend their group.

Nyhan would never say facts aren't important. His research indicates that countering misinformation with information may not be the most effective strategy. Nyhan’s research also indicates a “backfire effect” in the most ideological where any evidence to the contrary only makes a belief stronger.

What good then are facts?

Facts help us come up with our best beliefs. In the right settings, science and facts allow us to challenge some of our strongly held convictions and can help us see things in a different light. Especially if we can come to this conclusion in some way, shape or form on our own.

For example, science and facts work well in academia because we've constructed an artificial environment where people are more open to learning and the groups are ‘student’ and ‘teacher’ rather than left versus right, or conservative versus liberal. If you've ever been in academia or seen how academia works, however, you know that many of the decisions aren't based on science or facts or whoever has the best argument. Many of these decisions, even in this artificial environment, are made the same way decisions in the rest of the world are made. Emotionally. By people.

Still, academia provides an environment for learning and a process of peer-review that adds a level of credibility to research. Outside of academia conditions are different.

There's many ways to recreate these conditions outside of academia. I've found that people who I know and have developed a personal relationship with are much more likely to listen to facts and science. When you've developed a personal relationship with someone you are far more likely to be able to convince them of something than you are if you haven’t. You may think facts and science win them over, but more likely than not, it’s your relationship.

I've also found George Lakoff's advice on framing and speaking about your beliefs incredibly valuable. If you understand your beliefs and the beliefs of others, you can speak at a belief level rather than at a fact or policy level.

What’s your point?

How much time do you spend trying to win people over with facts? Or, do you know someone who spends an inordinate amount of time trying to win people over with facts?

If you or someone you know is spending a significant amount of time and frustration trying to win someone over by countering their belief with information, you may be spinning your wheels (unless of course, you do this in the right environment/manner).

In other words, there’s better things to do with your time. There are better ways to win people over.

You could be talking about your beliefs. You could be telling a story. You could be reframing issues. You could be targeting people more open to ideas. You could be creating environments where people are more open to ideas. You could be preaching and teaching rather than locked in some “You’re liberal” / “You’re stupid” war. You could be having fun. You could be buying someone a beer. You could be organizing.

You could be working to win people over.

What I've set up here, for example, is a conversation that anyone could have with a friend or someone who’s locked into a certain way of thinking about facts and "conservative" stupidity.

Kurt Gödel proved a limitation of mathematics. I’m using a self-referential example to demonstrate ways to overcome beliefs that put facts and science in an appropriate context. (And yeah, for the mathematically inclined I know there’s some issues with my analogy. But it was fun. If you want, see if you can spot the issue.)

I’m trying to convince you because I hate to see people beating themselves up in corporate divide-and-conquer (liberal versus conservative) games. If you're not doing this, great. If you are, maybe you find something useful here. Or maybe you know someone who is who you can help out.

It’s also important because corporate special interest groups are wiping out traditional beliefs (such as democracy and mutual responsibility) and replacing them with selfishness, corporate-rule (give to the top and it will trickle down) policies, and naked individualism (how do we not need other people?).

Politicians from both parties are moving to match these beliefs. If we’re forever arguing Democrat versus Republican, we’re missing the entire ground moving underneath both of these parties. When corporate special interest groups change the landscape, both parties move to match. This is really what’s going on when politicians say “move to the center”. The trick is that the center today is not the center of 30 years ago.

If we really want to shift things in a different direction, I believe we’re going to need a movement for democracy.

I’m also interested in what's worked for you. Who have you won over and how?

Please share in the comments or join the Komorebi Dojo (a group for sharing stories and ideas for teaching and winning people over).

---

David Akadjian is the author of The Little Book of Revolution: A Distributive Strategy for Democracy.