The area along the Pacific Coast north of California and between the Cascade Mountains and the ocean is home to many Indian nations who traditionally based their economy on the use of sea coast and river ecological resources. Among the Indian tribes who inhabited the Oregon coast were the Tillamook.

In historical reports, the name “Tillamook” is also spelled Killemuck, Kilamox, Callemex, and Killimux. The name roughly means “those who live at Nehalem” and was applied to all of the Salish-speaking Indians south of the Clatsops.

The homeland of the Tillamook ranged from Tillamook Head in Clatsop County in the north to the Siletz River in Lincoln County in the south. The Tillamook villages were near the mouths of the principal rivers in the area and the tidewaters of the Nehalem, Tillamook, Netarts, and Nestucca bays. The villages were located so that they had access to fresh water as well as easy access to salt water shellfish, edible roots and berries, trade routes, and game trails.

When the American Corps of Discovery led by Meriwether Lewis and William Clark came into the area in 1805-1806 they reported finding a village of Clatsop and Tillamook families near present-day Seaside, Oregon. The Clatsop and Tillamook are not linguistically related.

Like the other Indian nations of the Northwest Coast, the Tillamook had permanent villages which consisted of several houses, a women’s house, sweathouses, and a graveyard containing raised canoe burials. Tillamook houses were rectangular and constructed from horizontal cedar planks. Each house was occupied by more than one family and would have several hearth fires down the center. Two families would usually share a single fire. The side walls were lined with platforms for resting and sleeping. Mat partitions separated the sleeping areas of the different families.

The houses had gabled roofs supported by four large center support poles and a center ridgepole. The roof was composed of overlapping cedar planks.

In some instances, the Tillamook constructed subterranean houses. Like the other houses, these would have a gabled roof. In these houses, there would be a doorway in one end of the roof gable.

The Tillamook were generally classified as a hunting and gathering people whose subsistence depended on the harvesting of wild plants, fish, and animal foods. Plant foods included a variety of berries and camas. Fish, particularly chinook salmon, coho salmon, and chum salmon, were an important part of the diet. Fish were caught in nets, weirs, and traps. Elk were hunted in the fall. Other important foods included shellfish, sea lions, seals, and whales.

As coastal people, canoes were an important part of their daily lives and were the vital mode of transportation between villages as well as for subsistence activities such as fishing and hunting marine mammals. Canoes would be made from a single log and ranged from smaller “river” canoes which would hold up to 12 people to the larger “sea-going” canoes which could hold as many as 30 people. The canoes were painted black and had removable bow and stern pieces.

This small model of a Tillamook canoe is on display at the Tillamook County Pioneer Museum.

Shown above is a Tillamook dugout canoe which is on display at the Tillamook County Pioneer Museum.

With regard to personal adornment, both men and women painted their central hair part red. The men would wear their hair in a single braid, while the women would have two braids. Both men and women had tattoos and both sexes wore ear pendants. The men usually had one arm tattooed for measuring dentalium shells (used as currency) and only the men would wear nose pendants.

Shown above is a dentalium shell necklace on display at the Tillamook County Pioneer Museum.

Shown above is a display of Tillamook necklaces made from European trade beads. These are on display at the Tillamook County Pioneer Museum.

Shown above are some examples of Tillamook beaded bags on display at the County Tillamook Historical Museum.

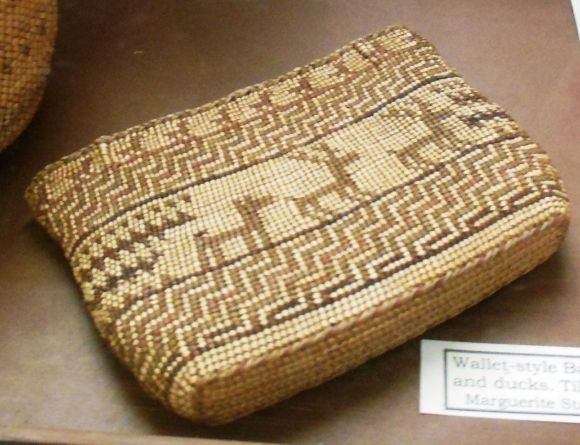

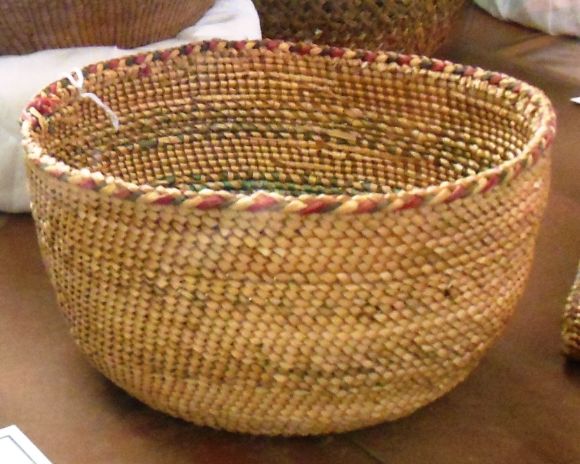

Weaving and basketry were an important part of the Tillamook material culture. The weavers and basketmakers were usually women. Many different kinds of baskets were made, ranging from large wicker baskets for carrying fish and clams to smaller baskets made from cedar bark fibers. The Coast Salish women would generally weave their baskets during the winter, but they would gather the materials for their basketry during the summer.

Shown above are some examples of Tillamook basketry on display at the Tillamook County Pioneer Museum.

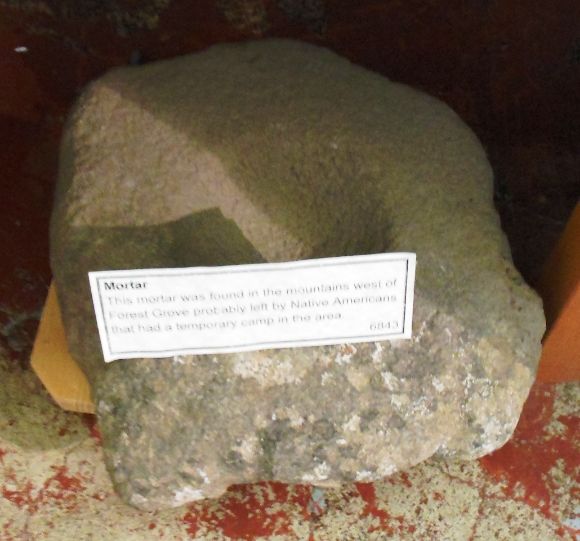

Many tools, such as projectile points, scrapers, mauls, axes, and other items, were made from stone.

Shown above is a stone mortar which was used for grinding seeds and nuts.

Shown above are collections of projectile points on display at the Tillamook County Pioneer Museum. While the looting of archaeological sites which resulted in collections such as these was often well-intended, the removal of this material means that its ability to tell us about the past has been destroyed because we have lost the context in which they were found.

The Tillamook also made tools out of bone and wood (see displays above).

Tillamook children were named at an ear piercing ceremony. At this time, a male elder, usually a spiritual leader, would pierce both the ears of boys and girls and the nasal septum of the boys. While there was feasting and dancing at the ceremony, this would vary according to the status of the parents. It was common for children to be given the names of relatives who had been dead for several years. As with many American Indian tribes, mentioning the name of the recently dead was not allowed.

For the first six months of life, babies were carried in a rectangular cradleboard. After six months, a canoe-shaped cradleboard would be used. When a child misbehaved, it would be lectured by a parent or an elder: physical punishment was not used.

At puberty, girls would be secluded and would fast for four or five days. An older woman would then take the girl into the woods where she would wait for a vision of a guardian spirit. The guardian spirit acquired at this time would remain inactive until middle age.

For boys, when their voice began to change, they would be sent into the woods to acquire a guardian spirit. During the vision quest, the boy would frequently bathe in a stream. The guardian spirit would usually appear on the third night and provide the boy with a spiritual song. As with the girls, the guardian spirit would remain inactive until middle age.

While marriage was generally arranged, the opinions of the potential partners was sought and valued. For marriage, village exogamy was preferred: that is, marriage partners were to be from different villages. Initially, the newly married couple would live in the groom’s village, but later they could select a different village.

The Tillamook had no political organization beyond the village level. In other words, there was no Tillamook tribal government.

Tillamook religion did not involve a creation myth or a concept of a deity. Writing in the Handbook of North American Indians, William Seaburg and Jay Miller report:

“The Tillamook recognized no deities as such. The earth itself was personified as omniscient and judgmental of the actions of people, but it was in no sense worshiped.”

Winter was the time of ceremonials and storytelling. For the Tillamook, winter was the time when spirits were more active and closer to humans. During the winter ceremonials, the “knowers” (those with guardian spirits) would sing their songs. The winter dance period was a time of renewal for the people and for the world.

At death, the body would be washed, the face painted red, and the body clothed. The body would then be wrapped in a blanket and bound with strips of overlapped cedar bark. After a two or three day wake, the body would be placed in a canoe. At the burial ground, the canoe would be placed on supports and another canoe placed over it. No food would be placed with the dead.

With regard to language, Tillamook is a part of the large Salish language family which is generally felt to have great antiquity in the Northwest Coast. Within the Salish language family, the Tillamook language is most closely related to Nehalem, Nestucca, Siletz, and Salmon River.

The Tillamook travelled north to the Columbia River where they traded for abalone shell, dentalia, buffalo hides and buffalo horn dishes, and for dried Columbia River salmon. The Tualatin Kalapuya often travelled into Tillamook country to trade and intermarriage between the two tribes was common.

The first reported contact between the Tillamook and Europeans came in 1788 when Robert Gray’s sloop Lady Washington sailed into their territory. One of the crew members, Robert Haswell, reported that the Tillamook had iron knives and that some were scarred with smallpox.

The second reported contact came with the Corps of Discovery. According to Lewis and Clark, the Tillamook numbered about 1,000 (some sources indicate 2,200). In 1838, a Hudson’s Bay Company census reported 1,500 Tillamook. A decade later, European observers reported that the population had declined to about 200 to 400 due to the impact of European diseases, including smallpox, influenza, and measles.