The United States at the dawn of the twentieth century was a nation transformed. The rural, agrarian nation of Jefferson's time and Jefferson's vision had embarked on a Hamiltonian evolution, the magnitude of which none of the founders could possibly have envisioned. The network of railroads begun scarcely three-quarters of a century before now stretched ocean to ocean and Gulf to Canadian border. Giant steamships criss-crossed the oceans, hauling cargo and passengers, and especially, immigrants. The steel skeletons of skyscrapers were suddenly thrust above the streets of Chicago and New York and would soon be rising in nearly every city of significant size. Steel bridges carried traffic over rivers, spanning unsupported over distances unimaginable a few decades before, Steam and electricity had replaced the waterwheel as a source of power at factories, freeing the nation's manufacturing industries to flee beyond their once river-bound constraints. Electric lights illuminated businesses and homes alike. And all this transformation was fueled by one particular commodity.

In the decade that closed the old century and opened the new – 1895 to 1905 – railroads, steamships, and the steel industry produced a nearly insatiable appetite for coal. Also, during that decade, more coal was mined in the United States than had been mined throughout its history. Coal was not only the sole source of power for railroads and steamships, it was the sole source of fuel for the production of electricity, the use of which was increasing dramatically each year. Electricity was also critical to the production of iron and steel for the building of the cities of Chicago, Milwaukee, and the other cities along the Great Lakes. Coal was King.

Davitt McAteer, Monongah: The Tragic Story of the 1907 Monongah Mine Disaster

As the coal industry rushed to satisfy the seemingly insatiable demand for its product, the stage was set for the worst coal mine disaster in U.S. history.

Agents of the Monongah Coal and Coke Company began quietly buying up mineral rights along the West Branch River, a tributary of the Monongahela, near a little town called Briar Patch (soon to be renamed “Monongah”, after the company that would come to virtually own it), not far from Fairmont, West Virginia, around 1890. The poor, isolated area was accessible only by dirt roads impassable in bad weather. The buyers were paying what seemed to be good money for underground mineral rights to the often-inaccessible land and they easily found ready sellers willing to collect a modest per-acre sum and still keep their land. The company representatives neglected to tell the landowners about their other venture, the Monongahela River Railroad Company, which would shortly run a spur from the Baltimore and Ohio tracks up the West Branch to Briar Patch, making the rights to the previously-inaccessible coal that lay below suddenly more valuable by orders of magnitude. After splitting the coal operation from the railroad operation in 1899, and selling off the railroad, the owners of the coal company formed the Monongah Company and leased its mines at now-renamed Monongah to the Fairmont Coal Company, which operated a number of mines in that part of West Virginia. Meanwhile, the Consolidation Coal Company which had begun operating just after the Civil War, had been swallowing up smaller companies ever since, including, in the opening years of the new century, the Fairmont Coal Company, which it continued to operate as a subsidiary. By 1907 Consolidation operated over 65 mines and employed tens of thousands of miners.

The rosters of these companies, their principals, boards, management, and investors shared impressively interconnected memberships of relatives, in-laws, business partners, political allies, and personal friends, in addition to the occasional shared member. The wildly entangled ownership and management of these companies included former and future U.S. Senators, governors, judges, and other federal, state, and local officials, in- and out-of-state bankers, railroad companies, oil companies, and even John D, Rockefeller. In some cases, the involvement of some of the players was concealed from other participants in the syndicates, and the actions of some members were frequently at odds with the interest of other members – often deliberately so. And the companies' entanglements didn't end at the “corporate borders”. The director of West Virginia's Department of Mines, for instance, was a former employee of Fairmont Coal Company (and would return to the mining industry after leaving his government “service”). In its dealings with government officials, the companies exhibited a largess that the miners who toiled in their mines could only envy. A gift of company stock to a state or federal official, or even a delivery of a railcar of free coal to heat the home of a local judge was regarded as just good business practice. The mining industry in West Virginia, and the government at both the state and federal levels at the turn of the century was a tangled Gordian Knot of power and influence, and the lack of regulation and oversight that came about as a result they considered a feature, not a bug.

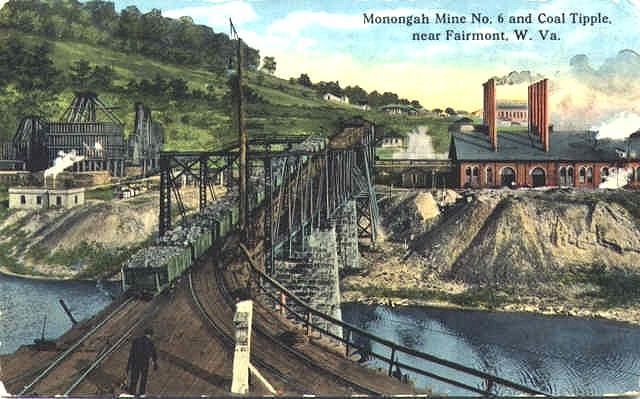

The mines of the Monongah Coal and Coke Company were sunk into the sloping bluffs that formed the west bank of the West Branch River. However, there being no suitable flat space on the west bank, the ore processing operations and the “cokers”, ovens which produced the valuable and profitable industrial coke for which the coal at Monongah was particularly well-suited, all had to be located on the east bank of the river where the land was flatter. To get the coal from the mines on the west bank to the processing operation on the east, massive tipples were constructed, coal car tracks elevated on a steel trestle, where a winch mechanism dragged the loaded coal carts out of the mine and across the river with a cable to the point where the carts were dumped preparatory to the coal being fed into the the sorters and processing equipment. The tipple for the No. 6 mine was particularly impressive, being the larges tipple ever built in the United States up to that time, nearly a quarter-mile long.

The tipple at Monongah No. 6

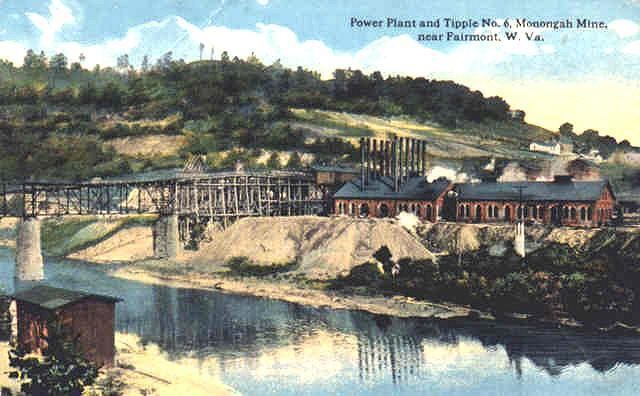

There was, however, a design flaw in the massive tipple. As trains, or “trips”, of loaded three-ton coal cars reached the crest of the tipple, there was a tendency for a car to occasionally hang up on the “knuckle” at the crest and stall the operation. Often, the car would break free of the obstruction after a moment and continue on its way with just a minor hiccup, but on rare occasions the car, and all that followed it, would uncouple from the car in front or become disengaged from the cable and roll back down into the mine opening, causing considerable damage on its way to crashing at the bottom, 400 feet below the entrance. To deal with this issue, since it didn't happen often and the cost of rebuilding the tipple to eliminate the problem was formidable, the company opted to install a “de-railer” switch which would allow the cars to be sidetracked before plunging back into the mine.

These break-aways didn't happen all the time, obviously. They were rare, if destructive, events, and the company was reluctant to pay a worker to sit there day in and day out tending the switch, waiting for the freak run-away. Consequently, they assigned the duty of throwing the switch in the event of a runaway to the nearest employee to the switch, the man who worked as the “oiler” for the massive fan that ventilated the mine, pumping fresh air in and, hopefully, forcing out the poisonous or explosive gases, predominantly methane, that tended to naturally accumulate in mines in the area.

Division of labor in the turn-of-the-century mines was dictated by ability. Strong, healthy men engaged in the grueling labor of actually extracting the coal. Young boys (some as young as eight) and elderly or disabled former miners were assigned lesser-paid, but less physically-demanding tasks such as sorting ore on the “picking tables”, tending mules, maintaining equipment, and so forth. The position of fan oiler was one of these latter positions. J.H. Leonard, the fan oiler on duty December 6, 1907 was one of the oldest employees still working at Monongah.

Another view of the No. 6 tipple.

Oiling of the ventilation fan was a critical operation. Because the huge fans lacked any sort of automatic lubrication system; the shafts, bearings, and gears required continual attention to ensure they remained adequately lubricated and spun freely. A shaft or bearing becoming too dry was presaged by a noticeable and audible increase in the engine load. Failure to timely apply more lubricant when this happened could result in a failure and considerable cost to the company.

Some time after 10:00 on the morning of December 6, a trip of nineteen loaded carts ascended the tipple. As the cars crested the tipple, one hung up briefly, as they frequently did. Leonard watched, but the cars did not seem to be rolling back down, just stopped as if holding while other cars were unloaded, as frequently happened. At that moment, Leonard thought he heard the telltale laboring of the fan engine, indicating a part needing oiling. He ran back toward the fan house, but at that instant, the coupling pin between two of the cars sheared off, and fourteen fully loaded cars of coal began a rapidly-accelerating descent back into the mine. Leonard realized what was happening and raced – to the extent he could – to the de-railer switch, but before he got there the last of the fourteen cars raced past the switch and disappeared into the mine opening. And then all Hell broke loose.

The cars raced back into the mine and crashed at the mine portal bottom. Along the way, the cars tore out electrical wiring and knocked down timber props, partitions, and curtains. When they hit bottom, a blast of air shot back into the mine entryways. The wreck disrupted the mine ventilation system deep within the mine, caused coal dust in the mine to swirl into the air, and forced methane gas from the voids and high spots.

At that instant, from deep within the mine an explosion rumbled, a terrible explosive report rocketing out of both mines [mine No. 8 was connected to mine No. 6 by ventilation shafts – ds], rippling shocks through the earth in every direction. The report was so loud it could be heard eight miles away in Fairmont. A second explosion followed almost immediately, and at the No. 8 mine entrances explosive forces rocketed out of the mine mouth like blasts from a cannon, the forces shredding everything in their path.

[…]

What at first seemed like distant thunder in a few seconds was transformed into a roar like a thousand Niagras. Like the explosion of a volcano the blazing gas reached the surface and vomited tongues of red flame and clouds of dust through the two slopes.

Davitt McAteer, Monongah: The Tragic Story of the 1907 Monongah Mine Disaster

Destruction of the No. 8 fan house prevented

ventilation of large parts of the mine and

hampered rescue efforts.

The blast erupted with such force that the brick power house housing the No. 8 fan was completely demolished and the thirty-foot tall, ten-ton fan housed inside reportedly hurled a half-mile across the river and embedded in the far bank. Roof supports were blown out and shot out the mine entrances as deadly projectiles. A long section of interurban railway track that passed in front of the mine entrances was destroyed, an interurban loaded with passengers coming within minutes of being in the blast zone at the wrong time.. Piles of debris blocked entrances and many roof falls occurred, blocking access to parts of the mine interior.

The force of a coal dust explosion is devastating, as the video of a controlled blast below demonstrates. As likely happened at Monongah, the dust is stirred up by the rail car passing over it or crashing to the bottom of the slope. Once airborne, the suspended dust quickly ignites and burns rapidly. In the confined tunnels of an underground coal mine, the explosive forces created are tremendous. Additionally, the force of the blast often stirs up dust in areas of the mine unaffected by the initial blast, setting in motion a chain-reaction of subsequent dust explosions throughout the mine.

However, the cause of the blast at Monongah would be hotly contested, as would the death toll. Contemporary news accounts, as in other disasters examined in this series, trumpeted wildly divergent casualty counts, some as high as a thousand. An account of the accident in the Washington, Pennsylvania Reporter the next day was typical:

Fairmont, W.Va. Dec. 7,—It was stated today by an official of the company that it may be weeks before all the bodies are recovered. Some may never be reached as posts of the mines no doubt have caved in.

As there are a large number of foreigners employed in the mines, the total list of the dead may never be known. The number is now listed at 425.

Deputy Mine Inspector R.S. Larru, of District No. 1, of West Virginia, arrived at the mines shortly after the disaster. He went part way in No. 6, but was overcome by fire damp and was compelled to return to the entrance. In his opinion, the explosion was caused from mine dust, which had accumulated, becoming ignited.

Officials of the company do not give credence to the theory of dust being in the mine from the fact that it was examined by one of the inspectors a few days ago. Mine No. 8, where the explosion first occurred, was one of the best-equipped mines in the country.

The Washington [PA] Reporter, “Officials Admit 500 Were Killed in Mine” (transcribed and posted online by Eastern United States Research)

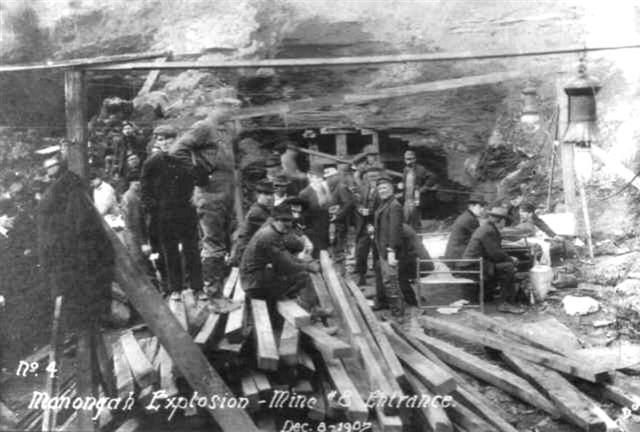

Rescuers at the scene first had to clear rubble from entrances.

In the minutes after the explosion, four miners emerged from a rocky outcrop, having made their way out of No. 8 through a natural opening. On one of the first rescue attempts after debris was cleared from the entrance to No. 8, a rescue party found a miner, dazed and injured, sitting upright on the corpse of another miner. Toxic gasses,

after damp and

black damp in the terminology borrowed from the Welsh, prevented further rescue attempts until fans could be brought in to clear the mine of the gases. These five miners would ultimately prove to be the only miners to leave Monongah mines Nos. 6 and 8 alive.

How many men (and boys) died at Monongah has never been, and likely never will be, established conclusively. Although the “official” death toll settled at 362, several factors point to this number being substantially underestimated.

First, the mines used the customary practice at the time of tracking the men entering and leaving the mines by means of a check board. Each man was assigned two numbered metal discs, or “checks”, at the beginning of a shift, which were hung on the check board.. When a miner reported for work and entered the mine, he moved one of his checks to the side of the board indicating he was inside the mine and carried the other with him. When he left at the end of his shift, he moved his tag back over to the “out” side. When the mines exploded, the debris blasting from the entrances obliterated the check boards, scattering the tags to the winds.

Additionally, the names on the check board likely never represented all the men in the mine at any given time. It was common for miners to bring sons into the mines with them, although not on the payroll, either to help train them for a future career in the father's occupation, or -- because the miners were paid, not by the hour, but by how much coal they mined -- to boost the father's production and, thereby, the family's income. And some of the miners, although hiring on and checking in as a single worker, were actually acting as a sort of ad hoc subcontractor, in fact bringing in a crew of men working under him. This was particularly common among new arrivals to the country, where a countryman among the more established miners served as interpreter, trainer, and crew boss for a group of recently-arrived immigrants. The company didn't appear to police any of these activities to any significant extent – they all meant more coal coming out of the mine, and more profit for the company.

Men clearing rubble from entrance.

And finally, entrance to the mines by outside entities was not controlled to any great extent (unless one happened to be a union organizer). All accounts of the casualties of Monongah tell of an unfortunate insurance agent who entered the mine that morning to try to sell miners insurance policies, and was still in the mine at the time of the explosion. But as Davitt McAteer discovered while researching his book, while all accounts agree that the insurance agent died in the explosion, his name never appeared on any of the official casualty lists.

Immediately after the explosion, company officials had embarked on an apparent campaign to understate the casualty count, each subsequent statement by a company official seemingly contradicting to the low side the statements previously made by other officials, systematically reducing the acknowledged death toll from as much as 550 to less than 300, and claiming, despite all evidence to the contrary, that there was only one single instance of a miner with a relative “working under the same check”.

Davitt McAteer's investigation of Monongah's official death toll revealed a number of discrepancies. For instance, although the count of unidentified bodies was variously reported as from 70 to 80, and according to the coroner's report, 71 were buried as “unidentified”, the official casualty count of 362 was based on lists of named victims whose corpses were recovered. There also appears to be no accounting for the possibility of un-recovered bodies, despite numerous statements by company officials and others that it would likely be impossible to recover all the bodies. He also found death notices in area papers of miners said to have been killed in the explosion who do not appear on any of the lists from which the official count was derived. Lists of deceased parishioners compiled by two local Catholic churches appear to have been ignored. McAteer's conclusion is that the actual death toll of Monongah is probably closer to the initial estimates of 500 to 550.

Like other mining disasters of this period, few of the victims were native-born Americans. The miners at Monogah were predominantly Italian and Eastern European, with a few other nationalities thrown in in small numbers. Of the hundreds who died, whether 362 or 550, only 74 confirmed victims were non-immigrant Americans. At Mononhgah, as elsewhere at the turn of the twentieth century, he victims, immigrant and native alike, were in many ways the commercial-industrial equivalent of cannon fodder.

Naomi Klein, in This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. The Climate, wrote of so-called “sacrifice zones”:

Running an economy on energy sources that release poisons as an unavoidable part of their extraction and refining has always required sacrifice zones— whole subsets of humanity categorized as less than fully human, which made their poisoning in the name of progress somehow acceptable.

And for a very long time, sacrifice zones all shared a few elements in common. They were poor places. Out-of-the-way places. Places where residents lacked political power, usually having to do with some combination of race, language, and class. And the people who lived in these condemned places knew they had been written off.

Klein, Naomi, This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. The Climate

While the above-ground footprint of the Monongah mines was relatively small, and its pollutants somewhat more benign by modern standards, the human toll on the once-isolated community that used to be known as Briar Patch, and especially among the immigrants who came to extract the coal hidden beneath it, certainly met the characteristics as a sacrifice zone. They, too, could easily be written off.

While many experts blamed coal dust, methane, or a combination, the company bitterly disputed this contention, claiming the blast had likely been set off by boys working in the mines setting off blasting caps or sticks of dynamite behind unsuspecting coworkers as a prank, a practice that had supposedly been reported previously. Blaming the miners themselves also served the company well. Legal principles at the time tended to regard actions of a worker that resulted in injury to a fellow worker as absolving the company of blame, even though the worker causing the harm was on duty and the responsibility of the company by modern standards. In the courts of the early twentieth century, companies in such circumstances could often evade liability altogether. Numerous investigations would ultimately focus on determining the cause of the blast, none of them arriving at conclusions that met with everyone's satisfaction.

The coroner's jury, perhaps swayed by the influence of coal companies in the area economy, and the testimony of mine inspectors who had given the mines a clean bill of health shortly before the explosion, rejected claims by the miners of accumulated coal dust.

We find from the evidence in our possession that A. H. Morris, Charlie McCane, John M. McGraw and about three hundred and fifty (350) others (whose names are made a part of the record herein), came to their death on the 6th day of December, 1907, by means of an explosion in Monongah mines Nos. 6 and 8, owned or operated by the Fairmont Coal Company, which was caused by either what is commonly known as a blown out shot, or by the igniting and explosion of powder in mine No. 8. As to which caused the initial explosion the evidence and opinions of mine experts and other witnesses were conflicting.

We further find from the evidence that the traces of gas in these mines were slight, and not considered dangerous, and dust which was created was removed or kept watered down as far as was deemed practicable, and that in operating these mines the company complied with the mining laws of the State.

As there are many unsolved problems connected with coal mine explosions in the United States, we recommend that Congress make an appropriation for the establishment of a bureau of investigation and information to aid in the study of the various conditions under which explosions occur, and as to how they may be prevented.

Coroner's jury report, quoted in The Illustrated Monthly West Virginian, “Monongah Mine Disaster”, January, 1908

The idea of the uncertainty regarding these explosion was echoed by others. Clarence Hall, the nation's leading expert on mine explosions, working with the Commerce Department to investigate the high number of fatalities in the mining industry, said:

When I enter a mine these days, it is with fear and trembling. We seem to know so little of these gas and dust explosions. Sometimes I feel that the poor miner has not a ghost of a show for his life when he enters a mine.

Davitt McAteer, Monongah: The Tragic Story of the 1907 Monongah Mine Disaster

One of the things that would come about as a result of the explosion at Monongah and disasters like it was a determination to find out.

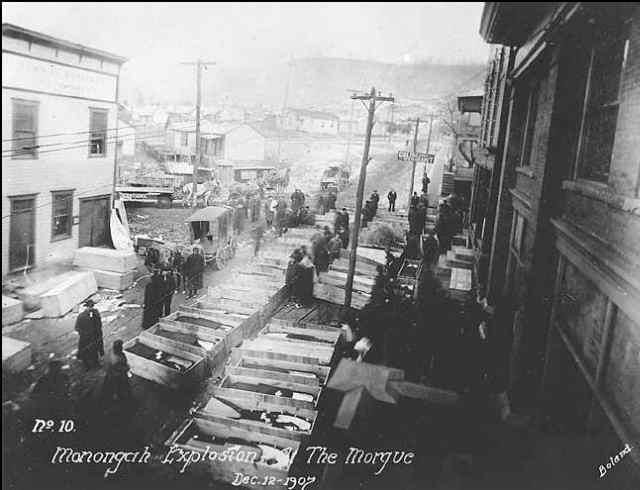

Coffins awaiting burial fill the streets.

The miners killed in the disaster at Monongah, three weeks before Christmas, left behind 252 widows and over a thousand fatherless children (based on early estimates, which, like the death toll, would be whittled down over coming weeks). Almost immediately, private citizens, both in the area and across the country, organized relief committees to raise money and collect food and clothing for the now-destitute families. The Red Cross also collected contributions (the first time the organization had ever marshaled its resources for a man-made disaster,) and foundations and individuals sent contributions. Donations poured in from fraternal organizations, and from overseas. The United Mine Workers, who had been defeated in an organizing drive the year before, sent a thousand dollars. While a representative of one of Andrew Carnegie's charities sent a relatively sizable donation, John D. Rockefeller, one of the original stockholders of the Monongah Coal and Coke Company, declined on three separate occasions. The lawyer for the parent Fairmont Coal Company, for his part, was careful to note that the company's contribution was a “gratuity or donation,” and not to be construed as any legal obligation of the company. Although originally estimating a quarter million dollars would be needed to properly provide long-term support for the families, the various fund drives by the middle of February had raised only $140,000.

Considerable infighting took place in the central relief committee organized to coordinate and distribute the contributions from various sources, with disagreements flaring over how to identify victims, how to determine eligibility, how the money should be divided and distributed, and so forth. The fact that the company was trying to secretly play a controlling role in the committee created tensions, as did suspicions between some largely Protestant charity organizations and fraternities, and the local Catholic churches identifying victims and helping to distribute aid. The Red Cross withdrew from the relief effort in the face of the fractiousness. Ultimately, 222 eligible widows received compensation of $200.00 each. Those with children also received $174.00 per eligible child. Dependent families of unmarried miners also received $200.00. Various other circumstances received similar amounts.

In the depths of winter, many penniless and facing starvation, the survivors of Monongah's dead had little choice but to accept the settlement. West Virginia law at the time had no provision for administrative or criminal penalties against the mining company, and the coroner's jury verdict exonerating the company and its officials of wrong-doing, blaming the supposedly mysterious and poorly-understood nature of mine explosions for the fatalities, effectively preempted any attempts to bring civil lawsuits against the company. The meager settlements from the relief committee would be all there was.

In the weeks following the explosion at Monongah, three other major mine disasters occurred, prompting the last month of 1907 to be nicknamed ‘‘Black December.’’ In the final tally, 3,241 American miners were killed on the job that year, the largest number killed in a single year in this country’s history. In spite of such horrific accidents, many mining operations, including Monongah, continued to ignore recognized safety precautions, using open candles instead of shielded lamps, employing cheap dynamite instead of controllable explosives, and skipping tests that would detect methane gas. Such practices were already being followed in Europe.

As a result of the national outcry following Monongah and the other mining disasters, Congress initiated fundamental reforms. In 1908, President Theodore Roosevelt advocated the formation of a federal agency to investigate mine accidents, teach accident prevention, and conduct mine safety research. Two years later, the Bureau of Mines was formed.

e-WV – The West Virginia Encyclopedia: Monongah Mine Disaster

In these “How regulation came to be” posts, we typically have a nice, neat little cause-effect sequence – “That happened, and these things were done in response.” With the mining industry in the first decade of the twentieth century, disasters were happening so fast, and in such magnitude, that it's difficult to cleanly assign such relationships to any single event with certainty. As the century dawned, a

coal mine explosion in Scofield, Utah produced what was then the deadliest mine disaster in U.S. history, with (again, “officially”) 200 dead, likely a significant understatement. Later in 1907, just twelve days after Monongah supplanted Scofield as the nation's deadliest disaster, 239 miners died in an explosion at Van Meter, Pennsylvania. Before the decade could close, 259 coal miners died in a

mine fire in Cherry, Illinois, dropping the Scofield disaster that began the decade to a distant fourth. Between these major events, smaller tragedies occurred with disturbing regularity. In the first decade of the twentieth century, over 22,000 coal miners lost their lives in mining accidents, then and now the deadliest decade in US coal mining history.

At the time, no federal regulation of the mining industry existed. Mine regulation was strictly the province of the states. In the wake of disasters like Monongah, that was about to change. Though it is popular to ascribe such regulatory innovations as the U.S. Bureau of Mines, the mine rescue stations, training programs, and so forth, to one disaster or another, the fact is that it was the sheer magnitude of the carnage going on underground, virtually under our feet, that prompted the wave of mine regulation that came about in the late nineteen-aughts and nineteen-teens.

Many of the responses to the mine disasters of the first decades of the twentieth century were weak and toothless. Thanks to the ability of mining interests to block legislation in Congress, the Bureau of Mines served mainly to conduct research and disseminate information on mine safety; the bureau initially had no powers of inspection or enforcement. The mine rescue station system was greatly expanded, but they could only respond to tragedies. They could do little to prevent them. The workers compensation laws that came about largely in response to these disasters in many ways were designed to shield employers from legal action. And so forth. While in some states these unimaginable human tragedies led to new or more stringent regulation of the industry, in others, including West Virginia, powerful mining interests effectively prevented any state-level legislative or regulatory reforms, or at the least, kept its impact minimal.

Still, even these weak efforts might not have happened at all had not the disasters occurred in the midst of an unprecedented wave of Progressive reform that swept the county in the first part of the century. Without the ear of sympathetic administrations under Theodore Roosevelt, William Howard Taft, and Woodrow Wilson -- however moderate they may have been in practice -- given the laissez faire inclinations of the conservative members of Congress, it is unlikely that even the weak reforms that ultimately were enacted would have come about.

Though it would take two more decades before the raw count of dead coal miners began to decrease significantly (during which time U.S. coal production increased by nearly 50 percent), the emphasis placed on safety, and increasingly muscular regulation, would eventually lead to a steady reduction in fatalities. With the increasing mechanization of mining operations beginning mid-century, the rate has fallen even further, to the point that annual coal mine fatalities have not exceeded 100 deaths since 1984, nor 50 since 1992.

Finally, I'd like to leave you with one last thing by which to remember Monongah. The United States Bureau of Mines was created after a long, and only marginally successful battle in Congress, which passed a severely-gutted mine safety bill in 1910. Joseph A. Holmes, a long-time champion for mine safety was named as its first director. Without inspection and enforcement authority, the bureau was left to rely on education as its chief tool to promote safe mining practices.

But in order to spread the gospel of safety to the local level, the bureau also established a program at each mine for miners, companies, and unions. The "Safety First" slogan, which was the program's slogan, would become the most wide spread industrial safety slogan ever used. After first being adopted in the mining community, it spread through railroad and steel industries and finally to all American industries.

Davitt McAteer, Monongah: The Tragic Story of the 1907 Monongah Mine Disaster

And that, dear Kossacks, is where regulation comes from -- not from bored bureaucrats sitting in an office in Washington trying to think up ways to make life miserable and expensive for some innocent and unsuspecting businessman, but from real human suffering and tragedy brought about, all too often, by people who shirk what should be obvious responsibilities, who neglect basic diligence, who sacrifice safety for profit. They bring suffering on those who trust them and their products, and society adopts measures to make sure it never happens again. We have to force them, through regulation, to behave as they should have been behaving all along. That's how regulation came to be.

Previous installments of How Regulation came to be: