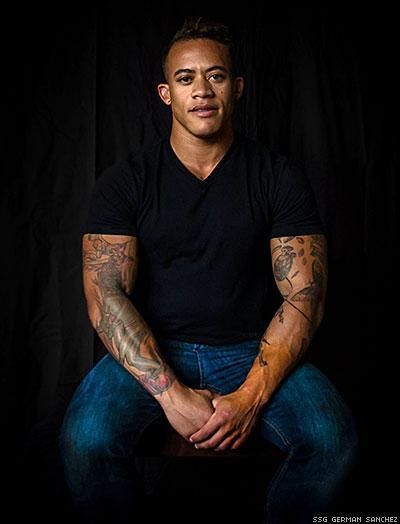

Shane Ortega ha served three combat tours...two in Iraq and one in Afghanistan...two as a marine and one in the Army...two as a woman and one as a man.

Shane Ortega ha served three combat tours...two in Iraq and one in Afghanistan...two as a marine and one in the Army...two as a woman and one as a man.

Sgt. Ortega is stationed at Wheeler Army Air Field in Hawaii. "Normally" he would be a helicopter crew chief. But he is temporarily (he hopes) grounded...and has been since last summer. So he's been doing human resources work instead.

Sgt. Ortega has been grounded since a medical test disclosed elevated testosterone levels. But he has a bigger concern. While all his government-issued ID recognize him as male, the Military's Defense Enrollment Eligibility Reporting System (DEERS) still lists him as female.

Sgt. Ortega’s Command has requested clear guidance from the DoD as to whether this means Shane can stay in the military or not.

--ACLU

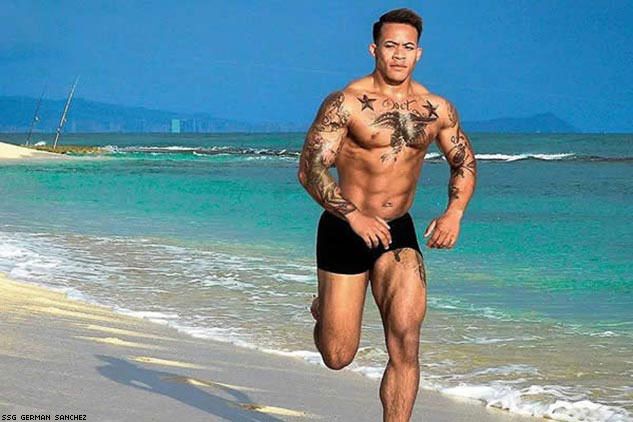

Meanwhile Sgt. Ortega concentrates on being perfect.

Honestly, I have to be perfect right now,” the 28-year-old Army helicopter crew chief tells The Advocate over the phone from Wheeler Army Air Field. He follows his words with a light laugh that will be repeated many times over the next 40 minutes, one that seems to dissolve clouds of self-pity before they can gather. “Like, I couldn’t get a speeding ticket. I can’t be late. I can’t forget to shave one day of the week. I have to be absolutely perfect.

I don’t think anyone really understands the level of perfection that I have to have right now that I stepped forward. But I understood the weight of the matter. It was part of what I juggled in my judgment before I decided to do that. And it’s really uncomfortable, to be honest. But if I don’t do it, it doesn’t help anyone else.

--Shane Ortega

DoD Instruction 6130.03 states that any type of gender-confirming clinical, medical or surgical treatment is evidence of "disqualifying physical and mental conditions." An Army doctor has determined that Sgt. Ortega has

tested negative for gender dysphoria.

Sgt. Ortega says his gender identity has never been an issue among his peers or his leaders. Not until his flight physical reached Fort Rucker, AL, where the Aeromedical Board is located.

When they finally reviewed my flight records, they were like, ‘This is a female with testosterone in their system.'

On the flip side, in the civilian world, according to the [Federal Aviation Administration], transgender people are allowed to fly. So it’s hilarious.

--Ortega

Today, Ortega finds himself in desk-duty purgatory, with no indication of when he can resume leading helicopter crews. His chain of command has now asked the U.S. Army point-blank what to do with him, placing subtle pressure on the trans military ban that has slowly been crumbling since the 2011 repeal of the “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy barring open service by lesbian, gay, or bisexual soldiers.

In return, the Army has offered mostly silence. “Essentially what the Army is saying is, ‘OK, Sgt. Ortega, we’re basically going to put you on the back burner for a while until we decide some sort of answer,” Ortega says. It’s now been over half a year.

Meanwhile, Ortega remains optimistic that his downtime might not be a total loss: He sees hope that the Army may be learning about transition-related medicine from his case in a way it hasn’t before. He explains that though the Army has specialists who understand endocrinology for transgender children, “there’s no one who specializes in … adult hormones,” making his lab reports “uncharted territory” that Army health care providers can begin gathering “baseline data” from.

Sgt. Ortega has passed his flight physical twice and his chain of command waits to reinstate him. His brigade's senior behavioral health office has cleared him of ever having had gender dysphoria.

I don’t have it. I’m comfortable with who I am.

--Ortega

While the term “gender dysphoric” is often bandied about colloquially as a synonym for “transgender,” Ortega — and, importantly, his military health care providers — appear to view the condition more as a temporary, or even avoidable, one.

For me, I think gender dysphoria is kind of like before people come out as gay or lesbian. That time period where you’re trying to figure out who you are. Once you acknowledge and actually know who you are, I don’t think you really suffer from dysphoria. I think you just need treatment at that time. It’s like saying, ‘I’m hungry.’ Until you get something to eat, you’re still hungry, you know? … You always know, ‘I’m hungry, I should eat a sandwich.’ So eventually, you’re like, ‘All right, cool, I got a sandwich.’

--Ortega

The distress, Ortega adds, doesn’t emerge inherently from being trans but comes from the social rejection that can sometimes accompany the identity, potentially layering anguish on top of that temporary hunger for gender congruity.

I’ve had hundreds of emails, to be honest, from active-duty service members as well as some reserve service members. I get people who say like, ‘How can I serve [openly as a trans person] like you?’ and I always have to explain to them, ‘There’s no protections or guarantees for you. You can take these steps forward, but you could be liable for separation.’ It’s really depressing.

--Sgt. Ortega

If the public doesn’t get to see this [trans] person actively serving, actively doing this job, and proving them all wrong, then they’ll never believe it can be done. That’s why I keep doing this. I have a few more years left in my contract. I figure I can keep pushing.

--Ortega

To win open service for transgender Americans, we need to put faces to the fight. I’m profoundly grateful that service members like Jacob Eleazer, Rae Nelson, and Shane Ortega have stepped forward to serve in this way. It's making a difference in our work at the Pentagon and in the public square as well.

Stories like Shane’s are more common than you think, and the pressure these service members feel is understandable.

The five transgender service members we took to the Pentagon last January to share their stories with senior leaders felt that pressure, as do the other transgender SPARTA members whose commands have chosen to retain them despite the regulations. But it’s infinitely preferable to the pressure thousands of other, less fortunate transgender service members feel: that of having to hide their true selves just to keep their jobs and keep serving.

--Allyson Robinson, director of policy, SPARTA

Although the Army appears to have temporarily halted the process of kicking trans people out, the policy still declares that they are unfit. That puts service members and their commanders in an untenable situation. It’s the policy itself that’s interfering with the military’s ability to do the job, not service members like Shane.

--Joshua Block, ACLU