Napoleon once famously said that an Army travels on its stomach. And it is thanks to Napoleon that the modern world has canned food. Troops, of course, grumbled about the quality of their rations anyway—just as they always have throughout history.

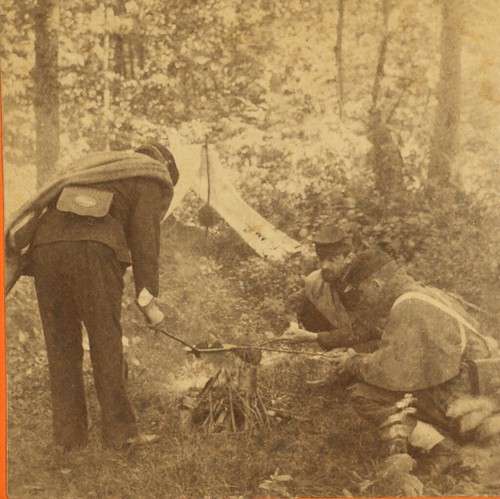

Civil War troopers cooking salt pork on an open fire. photo from WikiCommons

For most of history, "armies" were typically small militias, cobbled together from the local population and only in the field for a short period of time. For the most part, when on the move these armies lived off the land, purchasing or confiscating whatever food they needed from local supplies and farms along the way.

One notable exception to this was the Roman Legions, who made up the first permanent professional army in history. The Roman Empire had Legionnaries stationed in outposts at every far corner. This was made possible by Rome's extensive network of paved roads, which made it possible to reliably transport supplies to even the furthest reaches of the Empire. Each Roman soldier received a ration of two pounds of bread per day, supplemented by olive oil, meat and wine. Most of this was delivered over the Roman transportation network (most of Rome's grain supply came all the way from Egypt), but many permanent Roman outposts also had local fields and pastures where they could grow at least part of their own food supply.

It wasn't until the 18th century that large permanent professional armies began to appear again, most notably in the British Empire. When the American Revolution broke out in 1775, the British had already been using professional army units to put down colonial rebellions all around the world. Both the British Regulars and the American revolutionary militias depended upon locally-grown supplies for their rations. And though they foraged off the land whenever they could, both armies often found themselves in the field far away from any local supplies, and had to carry "garrison rations" along with them, stored in large baggage wagons that followed behind the column of troops. A typical food supply would include beef or pork (sometimes driven along on the hoof, and sometimes dried as jerky or preserved in salt), wheat flour or cornmeal for bread, and barrels of apple cider or spruce beer (in the days before sanitation, alcoholic brews were far safer to drink than the local water).

Fresh vegetables were usually lacking, as they could not be preserved for any length of time and were only available if there happened to be a ready local supply. The troops on both sides therefore suffered heavily from vitamin deficiencies caused by lack of fruits and vegetables, particularly in the wintertime. More British and Colonial troops died from diseases than died from cannon or muskets.

In 1795, Napoleon Bonaparte recognized that he needed a better way to feed his massive French Army, which was often operating far away from its supply sources in France. So he offered a cash prize to anyone who developed a way to preserve and carry large amounts of food. A Frenchman named Nicholas Appert took up the challenge. He developed a process to preserve food by placing it into a sealed glass jar and covering it with boiling water to cook the food inside. The heat killed any bacteria inside the jar and sterilized the food, and the airtight lid prevented any more bacteria from entering. The obvious flaw, of course, was the glass jar, which was heavy, expensive, and broke too easily. So in 1810, an English grocer named Peter Durand made a significant improvement--he replaced the glass jar with a can made from sheet tin, with an airtight lid that was soldered on. "Canned food" revolutionized the entire food industry. The British and French Armies quickly adopted them (they became known as "iron rations"), and commercial canned foods soon appeared on the civilian market. (Unknown to most, however, the early canned foods had a lethal problem--the tin and lead often leached out of the can into the food, and long-term use of canned foods often produced heavy-metal poisoning.)

The United States did not have the industrial capacity that Britain and France did, however, so when the War of 1812 broke out between the US and England, the American Army was still using the same basic rations that they had in 1776. Salt beef or pork was the staple, accompanied by large dry biscuits made from wheat flour called "hardtack", essentially large hard crackers, which kept better than bread or flour. By the time the Civil War began in 1861, some canned vegetables were becoming available (especially in the North), but both armies in 1865 were still living mostly on salt pork and hardtack (with the Confederates often substituting hominy grits). The hardtack was often referred to as "tooth-dullers", and to make it more palatable, troopers often used the butt of their muskets to pound it into powder, which they mixed with water and fried in pork fat to make "johnnycakes". In the North, Army quartermasters also developed a system for dehydrating vegetables such as potatoes, peas and beans, which they called "desiccated vegetables". For the most part, they were hard to cook and unpalatable, and the troops contemptuously called them "desecrated vegetables". The first time the US was able to provide a large proportion of canned rations to its troops was during the Spanish-American War in 1898--but even then, there were problems with inadequately-cooked and improperly-sealed cans that caused incidents of widespread food poisoning.

By the time of the First World War in 1914, canned foods had become reliable and safe, and huge amounts were shipped to the trenches, along with a smaller version of hardtack crackers that the troops called "dog biscuits". Canned vegetables were readily available (the most common being a canned carrot-and-turnip soup called "maconochie"), but the most common canned product was a corned beef hash that the troops referred to as "bully beef" (though some contemptuously dismissed it as "monkey meat"). The armies also set up field kitchens to try to provide fresh-cooked hot meals to its troops, but the constant artillery fire and the often-inadequate supply lines meant that frontline soldiers subsisted mostly on cold bully beef and crackers throughout the war.

After the First World War, the US Army tried to improve its supply process by incorporating a number of different canned foods into a single package which could be easily transported and distributed. The result was the "C Ration". This was a waxed cardboard case containing enough canned foods for three meals. A standard C Ration contained three cans with beef or chicken mixed with potatoes, rice or noodles, three biscuits, a chunk of fudge, some sugar cubes, a packet of coffee, and a P-38 can opener. The food was already pre-cooked inside the can and could be eaten either cold or warmed over a fire. The "C-Rat" was the standard food carried by troops in the Second World War. (Bomber crews were issued a special candy bar, which provided a lot of calories without taking up much space or weight--this was the "D Ration".) Later in the war, a smaller and lighter package was developed for use by troops on the frontline, called the "K Ration". After the war, the K Ration was discontinued, but the canned C Ration was still being carried by troops in the field throughout the Vietnam War.

In the 1980's, the Pentagon completely changed the way its rations were packaged and prepared. Canned foods were now gone--instead, the Army developed a series of freeze-dried foods that were carried in waterproof plastic envelopes, which were prepared by adding water and dropping in a small chemical packet that produced enough heat to cook the contents. They were called "MREs", for "Meals, Ready to Eat". When they underwent field trials in 1983, the troops labelled them "Meals, Rarely Edible" or "Meals, Rejected by Everyone". So some improvements were made (including a new variety of chocolate that wouldn't melt in the heat). Today, MRE's are still the standard rations in the US Army. They come in 24 varieties including kosher and vegetarian versions, and contain the main course (anything from beef stroganoff to Thai chicken) and a variety of fruits, vegetables and candy. Civilian copies of the military MRE are also very popular with hikers and backpackers.

Today, the Army's Combat Feeding Directorate is doing research to develop new types of military rations. Study is being done on a method of using pressurized air instead of heating packets to cook foods, and using osmotic dehydration to preserve meats and baked goods. Other research involves ways to include nutritional supplements such as omega-3 fatty acids and probiotics into foods without having them effect shelf life or taste. Another area of development is "performance optimization"--foods designed to provide individual soldiers with more energy, or, in one experimental program, to put needed vaccines into their food and inoculate them against local diseases.

MRE's ready for shipment. photo from US Army