Democrats have finally woken up to the reality that they can’t afford to wait until the after the 2020 Census to prepare for the next round of congressional and state legislative redistricting. Politico reports that top Democrats are organizing with key donors to invest in critical state legislative elections and gubernatorial elections over the next several years. Crucially, they are also considering ballot initiatives to create independent redistricting commissions, something that states like Arizona have done and what we have long advocated.

Republicans planned ahead last decade and poured millions into key state races in the 2010 midterm. Consequently, states with 55 percent of congressional districts are drawn to favor Republicans while just 10 percent are drawn to favor Democrats. This enormous disparity enabled Mitt Romney to win nearly 52 percent of congressional districts even though he lost the 2012 election by four points. That built-in Republican edge likely was the decisive reason why Republicans kept their congressional majority in 2012 despite losing the popular vote.

Many state legislatures such as Michigan are even worse, with Republicans consistently winning majorities despite losing the popular vote year after year. This sort of outcome is simply undemocratic. Ideally we should implement proportional representation, where parties win roughly the same seat share as their vote share, or at the very least Congress should pass nationwide redistricting reform legislation, but neither of these scenarios is likely.

There is a realistic possibility that the United States Supreme Court will start taking a much harder line against partisan gerrymandering, particularly if Democrats win the presidency and Senate in 2016 and replace the late Justice Antonin Scalia. However, Democrats can’t count on that possibility and must fight Republican gerrymandering state-by-state. Like a nuclear arms race, both parties reportedly plan to raise over $200 million for their 2020 redistricting efforts, a sign of just how important control of redistricting is for legislative elections. Let’s take a look at what that might involve.

Click to enlarge

Click to enlarge

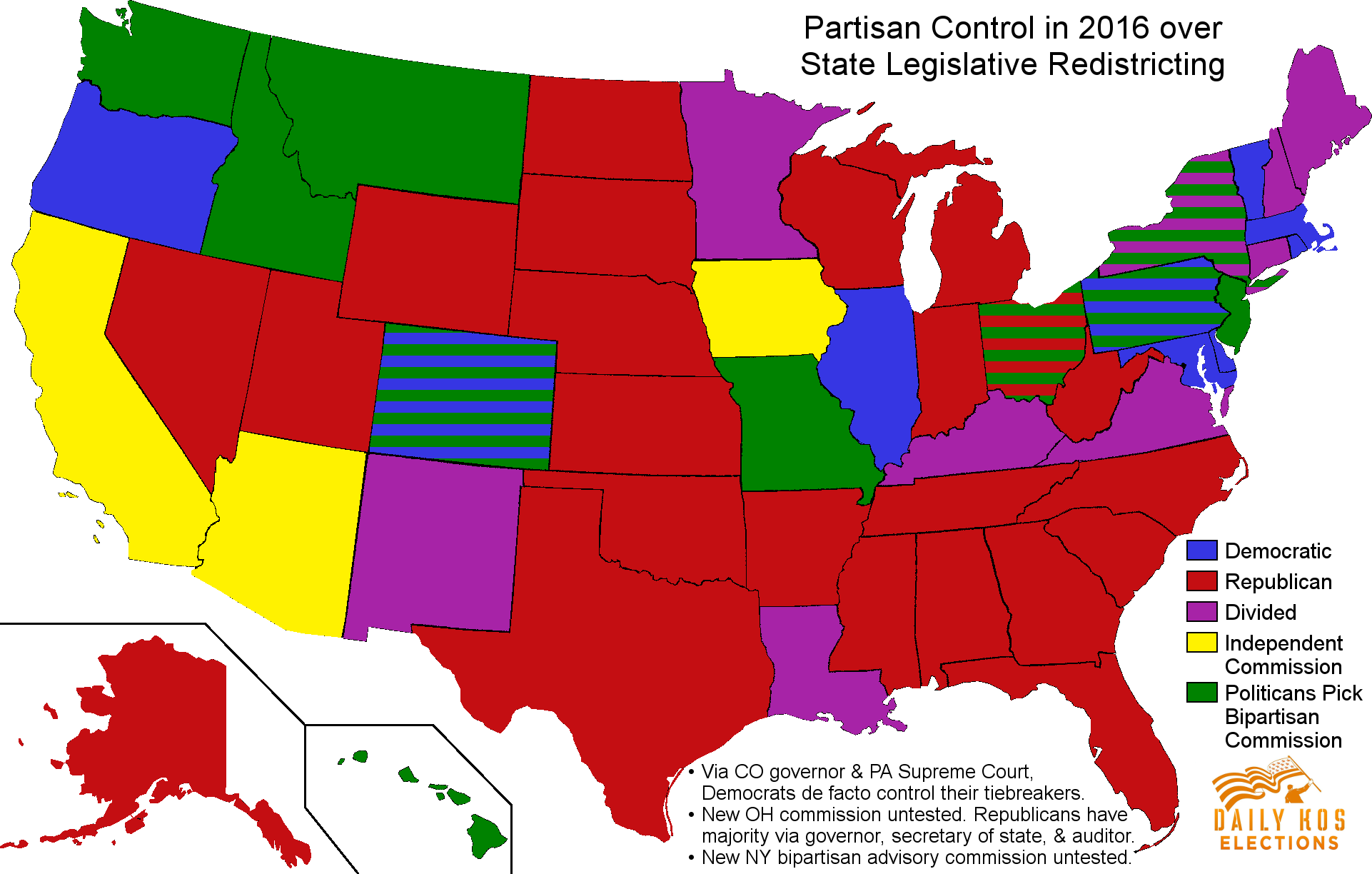

Republicans would be able to maintain their widespread dominance in congressional redistricting with today’s partisan control over the process. Democrats will need to make key gains to prevent that in states Obama won twice such as Florida, Michigan, Ohio, Nevada, and Wisconsin. Big Democratic states like California have independent redistricting, while New York and Pennsylvania have divided government, yet Republicans are free to gerrymander in Georgia, North Carolina, Texas, and many more. By contrast, Democrats control very few states where they might aggressively gerrymander to counteract the national bias toward Republicans.

Click to enlarge

Click to enlarge

The balance of power in state legislative redistricting is only a marginal improvement for Democrats. Several states have different rules governing the process than they do for Congress, giving Democrats likely control over Pennsylvania and Colorado. However, many of these states’ bipartisan commissions effectively impose political constraints on the degree of gerrymandering that a partisan legislature might not face in other states.

You can read more about state-by-state redistricting procedures from election law professor Justin Levitt’s invaluable site All About Redistricting.

Elections for governor are one of the most important ways to stop gerrymandering. A Democratic governor can often veto a Republican legislature’s gerrymanders, with the courts stepping in to draw relatively neutral maps. So many state legislatures are already heavily gerrymandered, making it nearly impossible for Democrats to win majorities in states like Ohio, where Romney carried a majority of legislative districts despite Obama winning the state. Thus it’s far easier to win a statewide election for governor where the electorate is more Democratic.

Click to enlarge

Click to enlarge

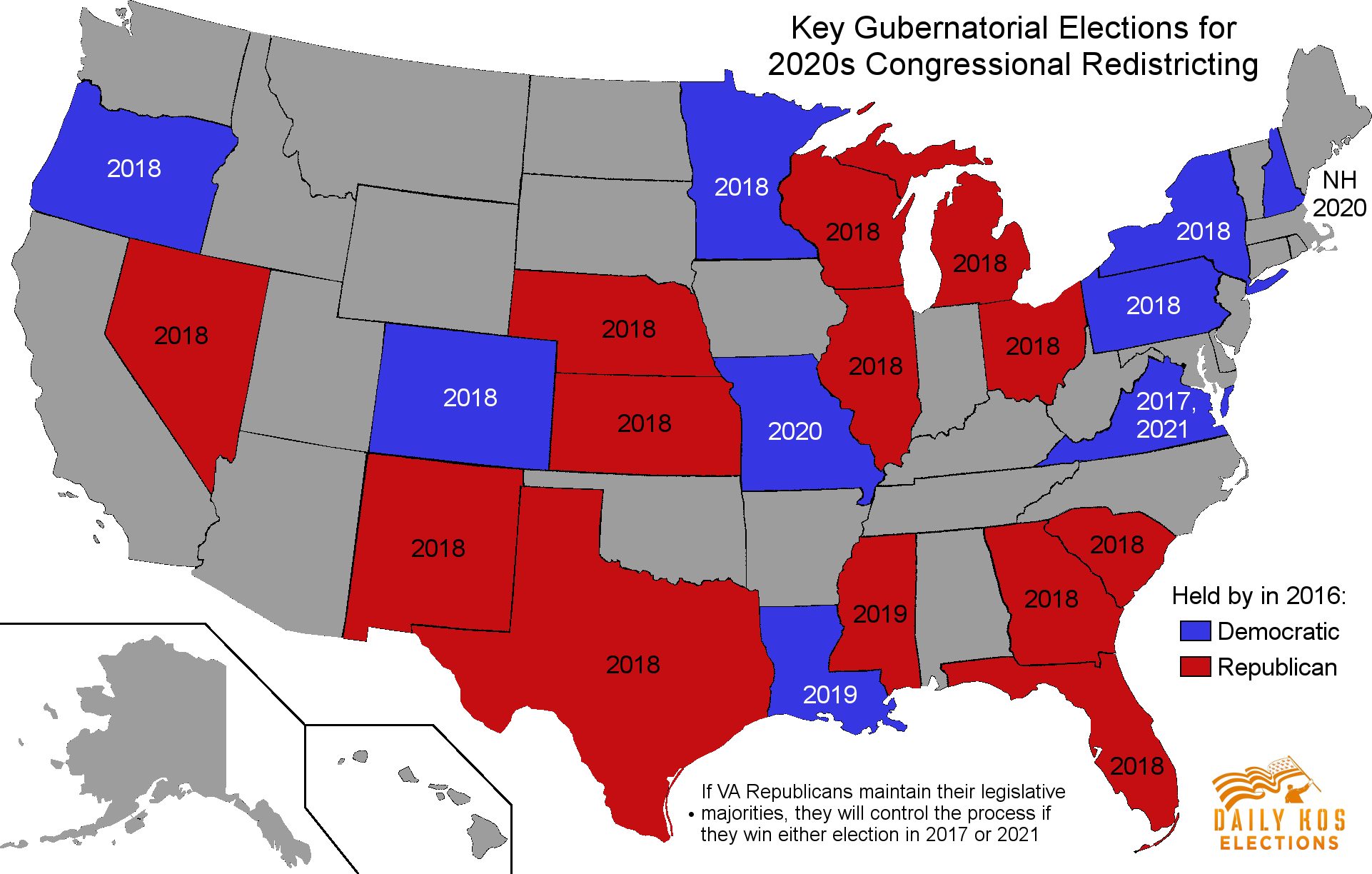

These are the state governorships Democrats need to focus on for congressional redistricting. Other states either have a redistricting commission, one-party dominance, legislative supermajority requirements, or the governor lacks the ability to veto redistricting. The most important races are likely Colorado, Florida, Illinois, Michigan, Minnesota, Nevada, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Wisconsin, where a closely fought battle for control over redistricting could make a difference of multiple seats in each state.

Republicans are defending seven states Obama won twice: Florida, Illinois, Michigan, Nevada, New Mexico, Ohio, and Wisconsin. Democrats are defending just two Romney states, Louisiana and Missouri.

Democrats will likely have to win both the 2017 and 2021 elections in Virginia to prevent a likely Republican-controlled legislature from simply timing congressional redistricting to coincide with a Republican governor in either 2021 or 2022. Kansas, Missouri, Nebraska, and sadly even Ohio currently have veto-proof Republican legislative majorities that Democrats would need to break to uphold a Democratic governor’s veto. Some of these states like Texas would likely be nearly prohibitive for Democrats to win, but the payoff would be monumental.

Click to enlarge

Click to enlarge

Certain states have slightly different rules governing the legislative redistricting process, meaning a few different gubernatorial races matter for legislative redistricting. Governors in both Florida and North Carolina can’t veto legislative redistricting, but both states are still important for Democrats to win so that they can appoint state Supreme Court justices who will enforce redistricting standards in their state constitutions. Both states saw sharply ideological court rulings over redistricting this past decade and Republican governors could cement conservative court majorities.

Fortunately for Democrats, Republican incumbents are term-limited in many important states like Florida, Michigan, Nevada and Ohio. Republican incumbents in Illinois, North Carolina and Wisconsin who can or are seeking re-election currently have poor approval ratings making them vulnerable to defeat. Democrats have fewer current states to defend, but will face critical open-seat contests in Colorado, Virginia, and possibly Minnesota, along with a key incumbent to defend in Pennsylvania. Lastly, Democrats might be better off if they replace New York’s Democratic Gov. Andrew Cuomo, who has been a thorn in the party’s side during redistricting.

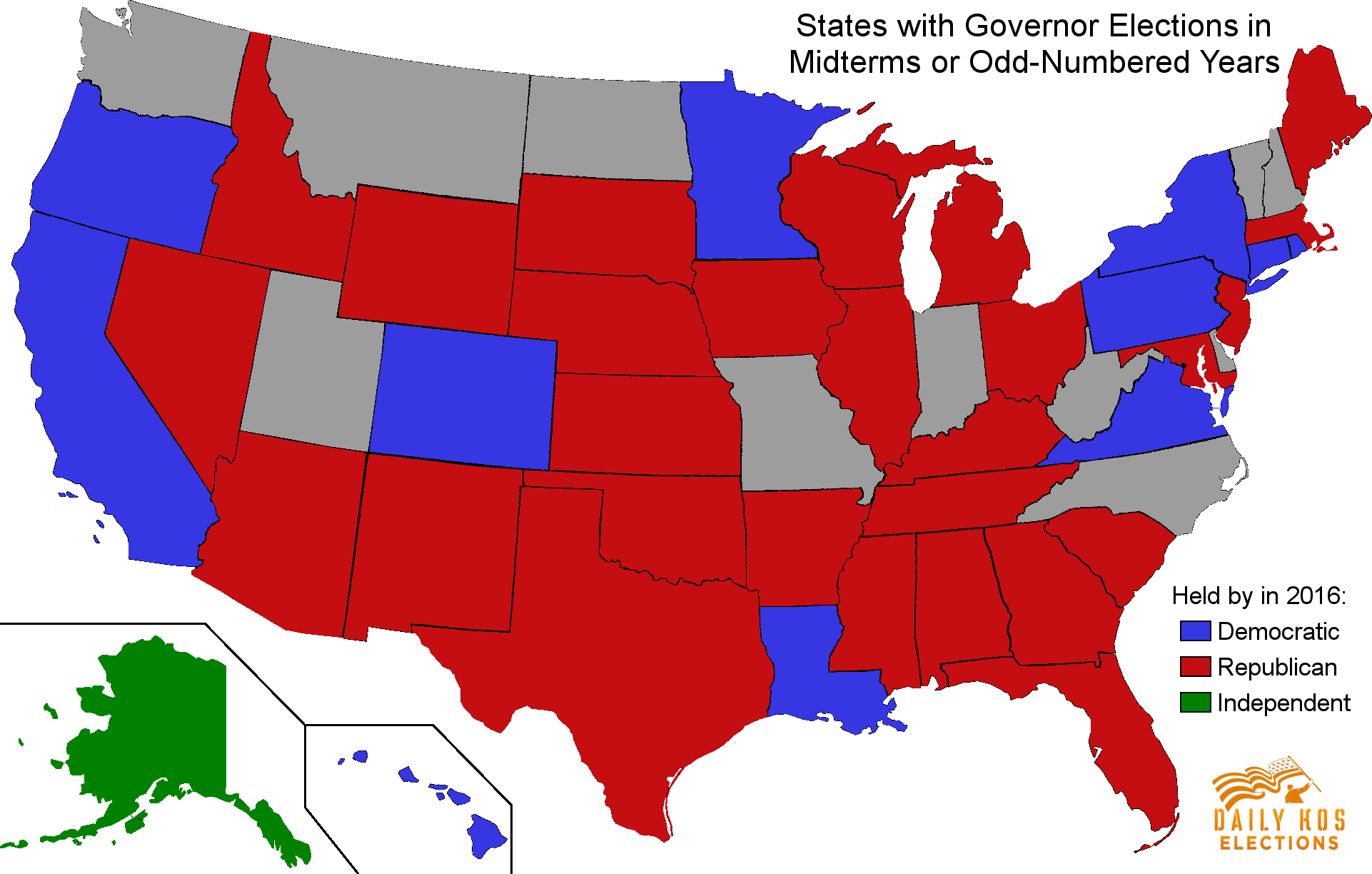

Unfortunately, 39 states with 88 percent of the population don’t elect governors in presidential years, meaning Democrats have to contend with midterm and odd-year electorates that are typically dramatically whiter, older, richer, and thus more Republican. Sadly, none of the most important states for congressional redistricting elects its governor in 2020. Even worse, midterm elections are often a backlash to the party in control of the White House, making Democratic gubernatorial efforts in 2018 potentially treacherous in the likely event that Hillary Clinton wins the 2016 presidential election.

The gubernatorial election calendar and the tendency toward backlash midterms are reasons why Democrats also hope to do well in 2020 legislative elections, which coincide with higher presidential turnout. Still, many states stagger at least their state Senate terms, with only half of seats up every two years. That means Democratic efforts to flip chambers like Florida’s Senate will require winning key races even in midterms, where districts that backed Obama in 2012 might have midterm electorates that would have voted for Romney.

Thanks to widespread gerrymandering and their stellar performance in the 2014 midterms, Republicans dominate state legislatures at a level not seen since the Civil War. They control 23 chambers across states Obama won twice, with one chamber in Colorado, Iowa, Maine, Minnesota, New Mexico, New York, and Washington and both chambers in Florida, Michigan, Nevada, New Hampshire, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Wisconsin. Democrats only control a single chamber in a Romney state, the Kentucky House. Democrats have plenty of room to improve and are poised to possibly flip several chambers in the 2016 elections.

To improve their position for redistricting, Democrats will likely try to win both chambers in Nevada and New Hampshire, upper chamber majorities in Colorado, Florida, New York, and Virginia, lower chamber majorities in Michigan, Minnesota, New Mexico, and either chamber in Pennsylvania and Wisconsin. New York is especially complicated because several turncoat Democratic state senators and even Democratic Gov. Andrew Cuomo effectively support Republican control.

Democrats will likely try to ensure Republicans don’t have veto-proof majorities in at least one chamber in Georgia, Kansas, Missouri, Nebraska, and Ohio so that a potential Democratic governor could successfully veto a Republican gerrymander. Democrats might also try to break the Republican supermajority in West Virginia, but because the veto override threshold there is just a simple majority, that would require actually winning back one of the chambers they held before 2014.

On defense, Democrats will attempt to hold onto their majorities in both chambers in Oregon, the Colorado and Kentucky lower houses, and the Minnesota Senate. They will fight to protect their veto-proof majorities in Maryland and Illinois, the latter of which only has the bare minimum number of lower chamber seats to override Republican vetoes. That’s especially important in Illinois, because divided government essentially forces a coin flip where one party gets a 50-50 shot at implementing its own gerrymander of the state legislature.

Click to enlarge

Click to enlarge

Click to enlarge

Click to enlarge

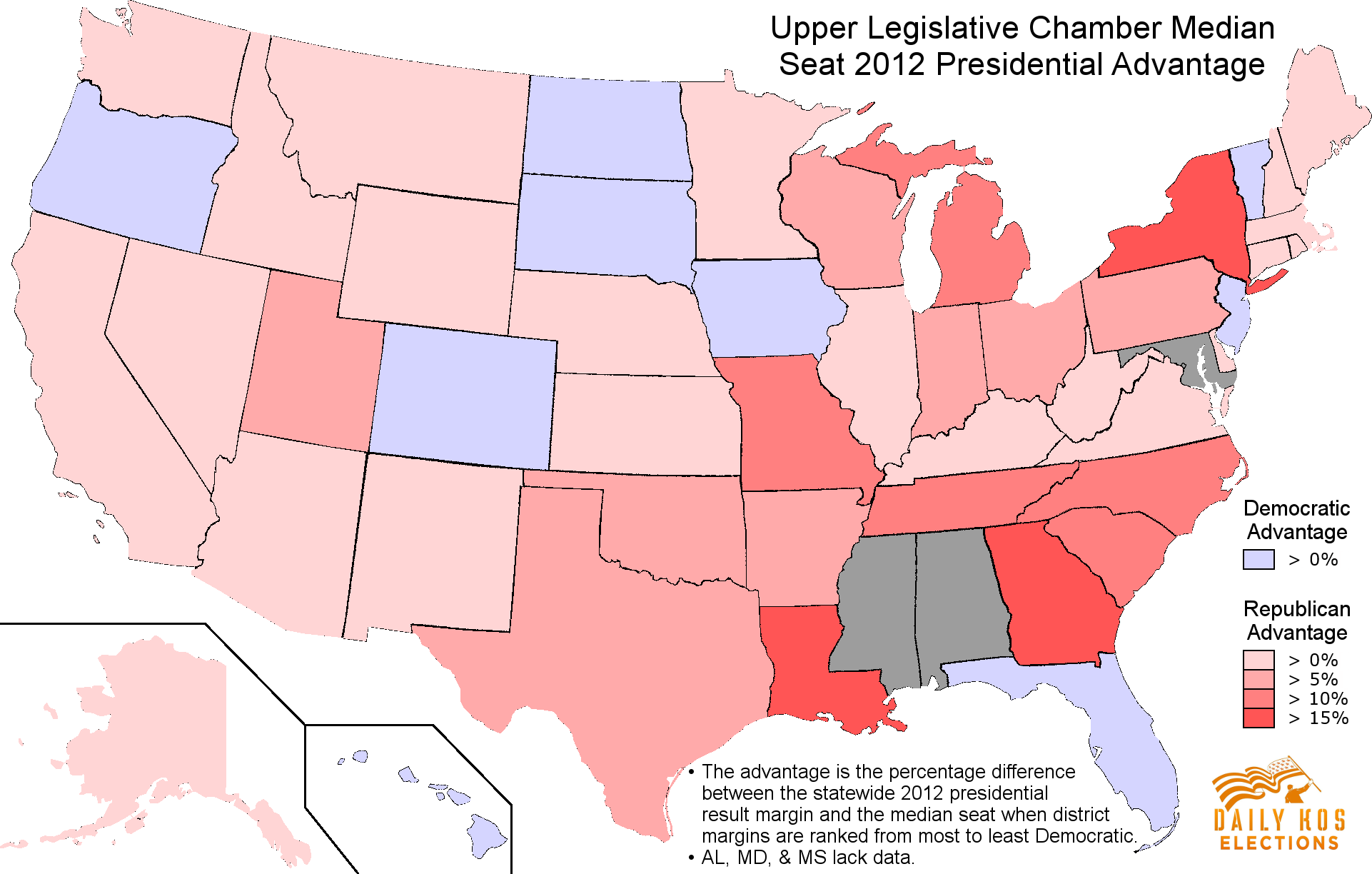

Unfortunately, the current gerrymandered and biased districts are a massive impediment to Democratic efforts to retake state legislatures. These two maps show the median seat advantage each party has in each state legislature using Daily Kos Elections’ calculations of the 2012 presidential result by legislative district. The advantage measures the percentage difference between the statewide 2012 presidential result margin and the median seat when district margins are ranked from most to least Democratic, so if Obama won the median seat by two points in a state he won by five points, Republicans would have a three point advantage.

The vast majority of legislative chambers have Republican advantages of several percentage points with some well into the double digits, particularly in the South and the Rust Belt. Even more unfairly, Obama won the statewide popular vote but gerrymandering helped Romney carry a majority of seats in both chambers in Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin, the lower houses in Florida and Virginia, and created a tie in the New Hampshire Senate. John McCain also won a majority in both chambers in Indiana and North Carolina despite losing both states in 2008.

Obama didn’t win a majority of seats in any state he lost. Even some of the few Democratic-drawn chambers still have a median seat to the right of the state, like Illinois or the New York Assembly. The handful of chambers with Democratic median seat advantages are still much less biased than the ones with Republican advantages.

Still, looking at the most important chambers, there is room for hope. Republican majorities rest on seats that voted for Obama in both chambers in Nevada and New Hampshire, the upper houses in Colorado, Florida, New York, and Virginia, and the lower houses in Minnesota and New Mexico.

Ballot initiatives are an excellent tool for fighting gerrymandering because they can sidestep both hostile legislators and partisan polarization among voters, making them a promising option in states where Democrats would have difficulty winning legislative majorities or gubernatorial elections. Redistricting reform measures of varying degrees have passed in several states, with Arizona and California notably establishing independent redistricting commissions.

The key states are Florida, Michigan, and Ohio, which have a combined 57 congressional seats, while a few smaller states could yield a modest difference too. We previously analyzed how nonpartisan redistricting in these states might have affected the 2016 elections, concluding that Democrats might have won nine to 18 more seats if all eight states had neutral maps. Legislative redistricting reform could also have a big impact even in small red states like Mississippi, while a truly independent commission could help solve the major problems with Ohio’s successful 2015 changes to its bipartisan legislative commission.

Democratic legislators in New Jersey have even debated using their legislative majorities to place constitutional amendment referendums on the ballot to reform the state’s flawed redistricting commissions, but have yet to make progress on that front.

If Democrats lose hard-fought gubernatorial elections in states like Michigan and Ohio, ballot initiatives could give them a backup plan in 2020 when turnout will be more favorable. Importantly, redistricting commissions can prioritize additional criteria that court-drawn maps might not value. Arizona’s commission promotes partisan competitiveness, while Florida goes even further than federal law to protect minority voting strength, although that state unfortunately still leaves redistricting in the hands of the legislature.

Republicans understand this tactic and have been supporting a 2016 legislative redistricting commission initiative in Democratic-drawn Illinois, although it’s unclear if the courts will allow it to proceed. However, Illinois is one of the worst states for geography bias. Democratic voters are overwhelmingly concentrated in places like Chicago while Republicans are more efficiently spread out. A commission could try to correct for this bias by ensuring that the median district has roughly the same partisan balance as the state, or by trying to increase the number of competitive districts, but this initiative does neither.

Purely nonpartisan redistricting could enable Republicans to frequently win legislative majorities despite losing the popular vote. Even under the current Democratic gerrymander, Republican Gov. Bruce Rauner still won 58 percent of state House districts when he won the 2014 election by just 3.9 percent. The current maps are clearly gerrymandered to help Democrats, but they are by no means a prohibitive factor against Republican majorities—the voters are. Democratic gerrymandering in Illinois is wrong and needs reform, but the proposed solution could be much worse than the original problem.

Republicans are also pushing reform in Maryland, one of the few other states Democrats drew, but it presents another problem. That isn’t geography bias, but because doing nonpartisan congressional redistricting only in Democratic-drawn states while Republicans continue drawing congressional gerrymanders in many others only exacerbates the problem nationally. Just like with a nuclear arms race, gerrymandering is an evil where unilateral disarmament is unhelpful. That’s why some Democrats like Maryland state Sen. Jamie Raskin have proposed pairing up reform efforts in multiple states controlled by opposing parties.

Many states elect their Supreme Court in head-to-head elections between two candidates, sometimes even on partisan ballot. These elections are important for redistricting for a few reasons.

North Carolina’s nonpartisan Supreme Court has a narrow four-to-three Republican majority, which upheld Republican state legislative gerrymandering this decade in a party-line ruling. A Democratic majority would be highly likely to curtail some of the worst excesses of Republican gerrymandering next decade and there’s an extremely important 2016 Supreme Court election where a Democratic victory could all but ensure Democrats control the court during 2020s redistricting.

Pennsylvania’s state Supreme Court appoints the tiebreaker to the state’s bipartisan legislative redistricting commission. During the 2000s and 2010s redistricting rounds, the Republican court majority enabled Republicans to draw aggressive legislative gerrymanders that denied Democrats a majority even in years when they won the popular vote, like 2012. Democratic candidates won a majority with five of seven seats in key 2015 Supreme Court elections and are well positioned to control the court during redistricting, but Republicans will surely put up a fight.

It’s plausible that other states might have successful lawsuits against Republican-led redistricting efforts if Democrats can gain majorities, such as in Michigan or Wisconsin, where Republicans control the court despite the state leaning Democratic. Democrats simply can’t ignore state Supreme Court elections, even when they are nonpartisan.

Democrats simply cannot afford another decade like the 2010s, when rampant Republican gerrymandering has all but locked Democrats out of majorities in Congress and many state legislatures despite popular vote wins. Hopefully the United States Supreme Court will start ruling all partisan gerrymandering illegal, but we must pursue an all-of-the-above strategy that includes ballot initiatives plus gubernatorial, legislative, and judicial elections.