Over the past month my foraging has reached a new level. As odd as it sounds, my surroundings seem to be subtly urging me in certain directions. (Left: Chicken Mushrooms by wide eyed lib)

Here are 2 examples. The Kentucky coffee trees I know about both have the ground beneath regularly raked. Unless I visit frequently, I can't collect many beans, so for a long time I've searched for a KCT in undisturbed woods. Recently I was hiking a very familiar trail when I noticed a small sapling with huge compound leaves. Sure enough, it was a KCT, and as soon as I looked up, I saw its parent, a tall tree hung heavy with ripe pods 20 feet off the trail.

A week ago on a different trail I decided to follow a deer path. A couple of yards in was the log you see here covered with edible and delicious chicken mushrooms.

Call me crazy, but I feel as though I've somehow passed muster and been admitted into nature's secret collective. Whatever's going on, I'm not complaining.

Covered: chestnut

[As always, if you're new to foraging and want to give it a try, please read the first diary in the FFF series for some important information.]

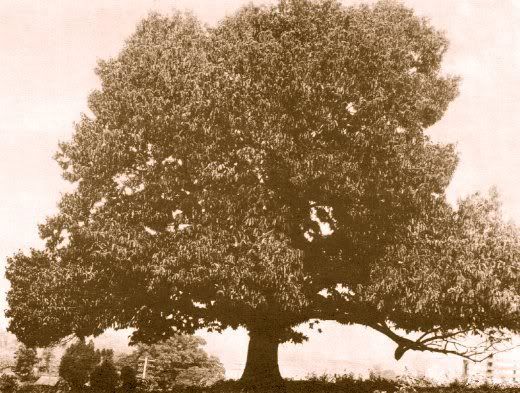

The story of the American chestnut (Castanea dentata) is a tragic one. In 1904 some of the chestnut trees lining the Bronx Zoo's roads started ailing-- their leaves were wilting and large cankers were splitting their bark. Two years later chestnut blight had spread to New Jersey, Virginia and Maryland, and from there it marched north, south and west at the relentless pace of 50 miles a year. Chemical agents couldn't kill the invasive fungus (Cryphonectria parasitica) and attempts to quarantine affected trees or create fungus "fire breaks" were completely ineffective. Eventually the fungus was traced back to the planting of a few Asian chestnut trees on Long Island. (The Asian trees, having evolved alongside the fungus, had developed effective strategies to lessen its impact.) By 1940, even the most remote stands of chestnuts in the East were afflicted. Around that time lumber companies decided to "salvage" what chestnut wood was left, so they rapidly cut down most of the remaining chestnut trees, including some that possibly had natural resistance. (Above Right: American Chestnut Historical Photo, courtesy of kristeen4878 at Photobucket)

The story of the American chestnut (Castanea dentata) is a tragic one. In 1904 some of the chestnut trees lining the Bronx Zoo's roads started ailing-- their leaves were wilting and large cankers were splitting their bark. Two years later chestnut blight had spread to New Jersey, Virginia and Maryland, and from there it marched north, south and west at the relentless pace of 50 miles a year. Chemical agents couldn't kill the invasive fungus (Cryphonectria parasitica) and attempts to quarantine affected trees or create fungus "fire breaks" were completely ineffective. Eventually the fungus was traced back to the planting of a few Asian chestnut trees on Long Island. (The Asian trees, having evolved alongside the fungus, had developed effective strategies to lessen its impact.) By 1940, even the most remote stands of chestnuts in the East were afflicted. Around that time lumber companies decided to "salvage" what chestnut wood was left, so they rapidly cut down most of the remaining chestnut trees, including some that possibly had natural resistance. (Above Right: American Chestnut Historical Photo, courtesy of kristeen4878 at Photobucket)

It's difficult to grasp the extent of the devastation without an understanding of the importance the American chestnut tree once had in eastern hardwood forests. In many places, one in every 4 trees was a chestnut. In parts of the Appalachian mountains, pure chestnut stands stretched for miles. The wood was hard and extremely rot-resistant, and it had been the primary wood for homes and barns east of the Mississippi for centuries. The tannins from chestnut trees were vital to the tanning industry. Chestnuts were an important source of food for people as well as bears, deer, wild turkeys, squirrels, raccoons, chipmunks, passenger pigeons and other animals. All in all, nearly 4 billion (yes, billion) chestnut trees died of the blight. Eastern hardwood forests (and the economy of Appalachia) have been trying to recover from the devastation ever since. (The American Chestnut Foundation has more information about the American chestnut and efforts to save it, including ways you can help.)

It's difficult to grasp the extent of the devastation without an understanding of the importance the American chestnut tree once had in eastern hardwood forests. In many places, one in every 4 trees was a chestnut. In parts of the Appalachian mountains, pure chestnut stands stretched for miles. The wood was hard and extremely rot-resistant, and it had been the primary wood for homes and barns east of the Mississippi for centuries. The tannins from chestnut trees were vital to the tanning industry. Chestnuts were an important source of food for people as well as bears, deer, wild turkeys, squirrels, raccoons, chipmunks, passenger pigeons and other animals. All in all, nearly 4 billion (yes, billion) chestnut trees died of the blight. Eastern hardwood forests (and the economy of Appalachia) have been trying to recover from the devastation ever since. (The American Chestnut Foundation has more information about the American chestnut and efforts to save it, including ways you can help.)

Because of the blight, most of the nut-bearing chestnuts you'll come across are either Chinese (C. mollissima), Japanese (C. crenata) or European (C. sativa), although there is one other native species in the Castenea genus that is somewhat blight resistant that I'll discuss below. (Left: Chinese Chestnut Bark by wide eyed lib)

All members of the genus have simple, oval to lance-shaped, toothed alternate leaves. The bark tends to be dark brown, with vertical grooves that are shallow and far apart. In early Summer, chestnut trees develop long catkins packed with tiny, whitish-yellow flowers. These give way to bright green, round, bristly burs which split when mature, revealing 2 or 3 dark brown nuts that are rounded on one side and flattened on the other. The American chestnut tree grows the tallest and has the longest leaves with a papery feel and a very light yellow midrib. Although its nuts are smaller than those of the European or Asian species, the meat is considered the sweetest and most flavorful. Of the 4 species, American chestnuts are the only nuts that are hairy. Chinese chestnut leaves feel waxy, are wider with a slightly darker midrib and often have an asymmetrical curve at the top.  European chestnut leaves are darker and smaller than American leaves, with a green midrib, and Japanese leaves are smaller still with a light midrib but not as light as on an American leaf. Japanese chestnuts also have the largest nuts. If you'd like to learn more about the differences between the various species, the species page on the American Chestnut Foundation's website has terrific comparative photos. (Right: Chinese Chestnut Leaves by wide eyed lib)

European chestnut leaves are darker and smaller than American leaves, with a green midrib, and Japanese leaves are smaller still with a light midrib but not as light as on an American leaf. Japanese chestnuts also have the largest nuts. If you'd like to learn more about the differences between the various species, the species page on the American Chestnut Foundation's website has terrific comparative photos. (Right: Chinese Chestnut Leaves by wide eyed lib)

Because landscapers love the various species, it's difficult to give ranges for them. The Japanese chestnut is naturalised only in Florida, the Chinese chestnut in the Appalacian Mountains, and the European chestnut mostly in the Mid-Atlantic states, but that certainly doesn't mean you couldn't find any of these trees in, say, California. All species are more common in the eastern 2/3rds of the U.S. and Canada, but it pays to keep an eye out for them just about anywhere with sufficient rainfall.

In addition to the magnificent American chestnut, North America has another native chestnut species, C. pumila, more commonly known as the eastern or Allegheny chinquapin. It is smaller in all ways than its more famous brother, from its height to its leaf size to its burs and nuts. Like all species in the genus, the nuts are edible, though their small size makes getting enough nut meat for a recipe a somewhat daunting task. They're found mostly in hilly or mountainous areas from Pennsylvania to Georgia and as far west as Texas. They're at least somewhat immune to chestnut blight.

The west coast of the U.S. has 2 species that used to be considered part of the Castanea genus but have since been reclassified into a genus of their own, Chrysolepis. Despite the reclassification, the bush chinquapin (C. sempervirens) and golden chinquapin (C. chrysophylla) still have edible nuts and share many features with the various chestnut species. The main differences are that the West Coast species are evergreen and lack the teeth of the true chestnut species. Their burs and nuts are small like those of the eastern chinquapin.

The nuts of all of these species are treated the same way. Remove them from their burs and perforate the shells so they don't explode. (The classic method is to make an X with a paring knife in the wider end, but wvvoiceofreason suggested last week that a couple of good pokes with an ice pick is much more efficient.) Then roast them at 425 for 15 to 25 minutes, depending on size. Once roasted and shelled, chestnuts can be eaten as is or used in stuffings, breads, cookies, cakes, soups, casseroles... well, just about anything. They have a mild nutty flavor that compliments both sweet and savory dishes. (Left: Chinese Chestnut Bur by wide eyed lib)

The nuts of all of these species are treated the same way. Remove them from their burs and perforate the shells so they don't explode. (The classic method is to make an X with a paring knife in the wider end, but wvvoiceofreason suggested last week that a couple of good pokes with an ice pick is much more efficient.) Then roast them at 425 for 15 to 25 minutes, depending on size. Once roasted and shelled, chestnuts can be eaten as is or used in stuffings, breads, cookies, cakes, soups, casseroles... well, just about anything. They have a mild nutty flavor that compliments both sweet and savory dishes. (Left: Chinese Chestnut Bur by wide eyed lib)

Unlike acorns which are so abundant some years that they can be gathered at leisure, chestnuts are very popular with all kind of wildlife, and the nuts will disappear as fast as they hit the ground. If you find a good tree, keep a close eye on it as nut season approaches and try to pick or shake the burs from the tree right as they're starting to split.

One note of caution: people sometimes confuse chestnut trees with horse chestnut or buckeye trees (all Aesculus genus). This mistake can be fatal, but it's easily avoided. Horse chestnut and buckeye trees have huge, palmately compound leaves with about 7 leaflets. The individual leaflets somewhat resemble a chestnut leaf, but chestnut leaves are simple rather than compound. In addition, horse chestnut and buckeye flowers are showy and white on upright spikes as opposed to the dangling catkins of chestnuts. Buckeye nut husks are smooth, while horse chestnut husks have short thorns that are much sparser than chestnut's hairy-looking spines. Both buckeyes and horse chestnuts also have only 1 nut inside each husk. It's not hard to distinguish between them, but it's important to make sure you can before gathering chestnuts.

See you next Sunday!

_______________________________________________________

If you're interested in foraging and missed the earlier diaries in the series, you can click here for the previous 27 installments. As always, please feel free to post photos in the comments and I'll do my best to help identify what you've found. (And if you find any errors, let me know.)

Here are some helpful foraging resources:

"Wildman" Steve Brill's site covers many edibles and includes nice drawings.

"Green" Deane Jordan's site is quite comprehensive and has color photos and stories about many plants.

Green Deane's foraging how-to clips on youtube each cover a single plant in reassuring detail.

Linda Runyon's site features only a few plants but has great deals on her dvd, wild cards and books (check out the package deals in particular).

Steve Brill's book, Identifying and Harvesting Edible and Medicinal Plants in Wild (and Not So Wild) Places is my primary foraging guide. (Read reviews here, but if you're feeling generous, please buy from Steve's website.)

Linda Runyon's book The Essential Wild Food Survival Guide contains especially detailed information about nutritional content and how to store and preserve wild foods.

Samuel Thayer’s book The Forager's Harvest is perhaps the finest resource out there for the 32 plants covered. The color photos and detailed harvest and preparation information are top-notch.

Steve Brill also offers guided foraging tours in NYC-area parks. Details and contact info are on his website.

Finally, the USDA plants database is a great place to look up info on all sorts of plants.

<-- Previous Diary in Series

Next Diary in Series -->