In Part I of the Hotel Fires of 1946, we were introduced to the three fires of June, 1946 that shocked the nation. In just sixteen days, fires at the LaSalle Hotel in Chicago, Illinois; the Canfield Hotel in Dubuque, Iowa; and the Baker Hotel in Dallas, Texas claimed a total of ninety lives. Our story concludes inside with the worst hotel fire in United States history and the lessons, regulations, and a fundamental shift in national attitudes toward the government's authority to regulate public safety brought about by the fires of 1946.

In the three fires covered in the first installment of the Hotel Fires of 1946, we noted striking similarities in two of them. While the worst damage of the daytime explosion and fire at the Baker Hotel in Dallas was principally confined to a sub-basement area likely well-closed-off from the public areas of the hotel, at both the LaSalle and the Canfield hotels, fires began at night in lounge areas as guests were sleeping and quickly spread through lobbies and into other areas of the hotels. Both buildings, touted as being of "fire-proof" construction, in fact contained dangerous combustibles that provided generous quantities of fuel for the fires that broke out and produced copious smoke and fumes; poor designs, with false ceilings and walls of flammable materials concealing hidden voids where fire could spread undetected; openings from lobbies to mezzanines, open stairways, and ventilation shafts that allowed fire to easily spread to other areas of the hotels; and a lack of sprinkler systems and fire alarms all contributed to the disasters. And in both the LaSalle and Canfield fires, hotel personnel failed to call the fire department as soon as the fires were discovered, losing valuable time that contributed the loss of life.

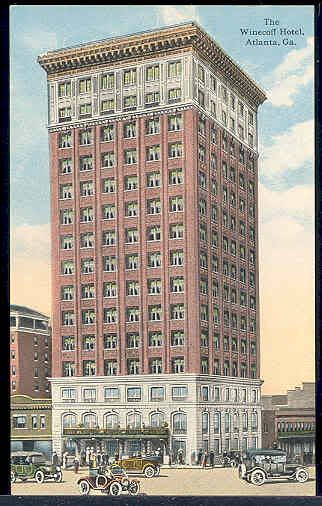

The Winecoff Hotel, Atlanta, Georgia |

On the fifth anniversary of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, all these factors would again come into play, this time in Atlanta, Georgia.

The Winecoff Hotel at 176 Peachtree Street in Atlanta represented what was not an unusual phenomena in the advertising world of the mid-twentieth century -- a hotel without sprinklers, fire escapes, or even an alarm system promoted as "absolutely fireproof". It also harbored many of the other hazards that had contributed to the tragic hotel fires that preceded it in 1946. On December 7, 1946, the sham of the Winecoff's advertising image would be tragically exposed.

Built in 1913 on one of Atlanta's highest hills, the Winecoff was considered among the finest hotels in Atlanta, even the entire southeast. It stood fifteen stories tall, towering over the buildings around it. The fact that the Atlanta fire department ladder trucks could only reach eight stories was about to become an enormous shortcoming.

On the night of December 7, 1946, the hotel was filled to capacity with over 280 guests including shoppers, travelers, World War II soldiers eager to rebuild their lives, and 40 of Georgia's most promising high school students who had come to attend a mock legislation.

Around three o'clock in the morning, the elevator operator noticed the smell of smoke around the fifth floor. Panicked, she descended to the lobby then stumbled out of the elevator screaming, "Fire! Fire!"

Peachtree Burning: The Night of the Fire

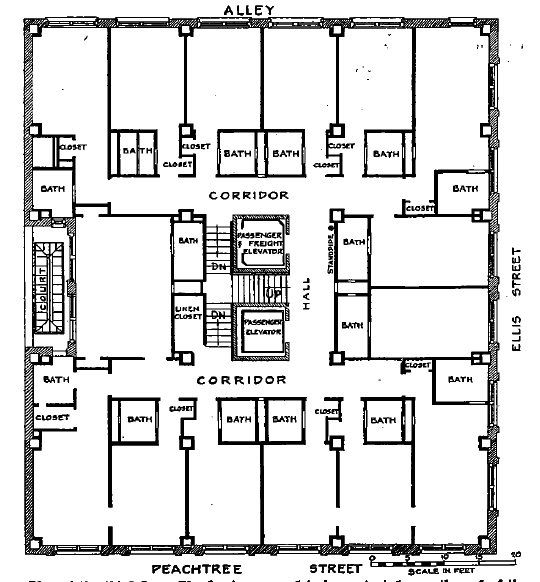

Typical floor plan of the Winecoff Hotel guest room floors. The single central stairwell configuration became, effectively, a chimney drawing smoke and flames into the upper floors of the hotel. |

By the time hotel staff discovered the fire, the third, fourth , and fifth floors were largely engulfed. The wooden doors to the stairwell would have offered little resistance to the fire; the issue was moot, however, since many were propped open. The central -- and only -- stairwell was essentially turned into a chimney, allowing flames to be drawn upward into the hotel's upper floors. Open transoms above doors in the pre-air-conditioning era offered easy passage to the spreading smoke and fire. In the investigation following the fire, more than half were found to be open. Wall coverings and decorations such as the burlap-like wall covering to wainscot height in the corridors and up to seven layers of wallpaper in the rooms provided ample fuel for the blaze.

The fire spread from floor to floor through the unenclosed stairway by ignition of the combustible interior finish in the corridors and halls, aided by the draft produced through open wood transoms over the wood doors to those guest rooms in which the exterior windows had been thrown open to await rescue or to obtain air to maintain life.

Wood doors and transoms were burned away on all floors from the fourth to the thirteenth, with almost total destruction of all combustible material from the sixth to the twelfth floors. There was little physical damage except from the heat ans smoke on fourteenth and fifteenth floors...

[...]

As in he Hotel LaSalle fire, there were rooms totally burned out with transoms open, and others only slightly damaged where the transoms were closed.

National Fire Protection Association Journal

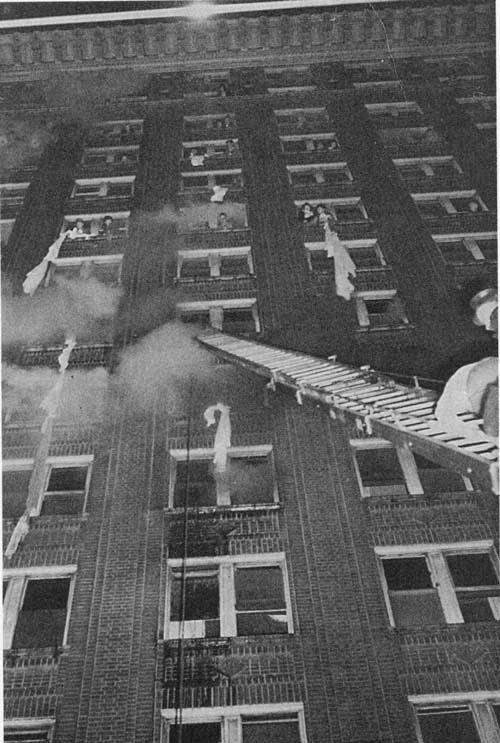

Note the bedsheet ropes hanging from the windows. Several guests were able to climb down them to reach ladders, but many more fell to their deaths. |

With no fire escapes, the central stairwell up which the fire was spreading was the only means of egress. It was quickly rendered impassable, trapping the guests -- many still sleeping at three a.m. -- on the floors above. As the situation deteriorated, desperate guests, as they had in Chicago and Dubuque, fashioned makeshift ropes of bedsheets and attempted to escape down them, though unlike Chicago and Dubuque, many attempting to escape in this way lost their grips and fell. But several on upper floors were able to use the bedsheet ropes to reach fire department ladders below. Some were able to escape by crawling over a ladder to a building across a ten-foot alley, though others fell or were knocked off by people above trying unsuccessfully to leap across the chasm to safety. Many were saved by jumping into nets, though at times so many jumped simultaneously that firefighters were unable to catch them all. As the fire intensified, the trapped guests grew even more desperate.

Fear had reached such a fevered pitch that panic-strickened guests became desperate, and nothing short of a human rain shower ensued. Several firefighters fell to their deaths or were injured after being knocked off their ladders by falling bodies. Mothers hurled their babies from windows only to follow them to their deaths.

Peachtree Burning: Firefighting Efforts

[The NFPA report on the fire says only that firemen were injured by falling bodies. No firefighter deaths from falling bodies are noted in its report. Also, only one instance of a mother throwing her children out a window and jumping after them is documented in any of the official reports I encountered. -- ds]

In the aftermath of the Winecoff fire, survivors and victims families sought redress from the people responsible for the circumstances that resulted in their loved ones deaths, with an outcome that will be all too familiar to readers of our little series on regulation:

A fireman climbs across a ladder from an adjacent building to the Winecoff. Some guests were rescued in this manner. |

By the time Mayor Hartsfield arrived at the scene, nothing remained but smoldering embers and the smell of burnt flesh. According to a report filed by the National Board of Underwriters, a partially burned mattress found on the third floor gave rise to the conclusion that a careless and possibly intoxicated guest dropped a cigarette onto it, thus starting the fire.

Unconvinced, Mayor Hartsfield invited fire experts from across the country to conduct their own investigations and several arson theories quickly emerged. But the press and the public in general were more concerned about why an "absolutely fireproof" hotel lacked fire escapes, a sprinkler system and fire alarms and less concerned with theories of arson. They demanded culpability from the hotel's owners and operators and the victims families were eventually awarded a $3.5 million negligence lawsuit which they unfortunately would never receive.

Peachtree Burning -- Investigation: Accident or Arson?

The Winecoff fire remains today the worst hotel fire in our nation's history. 119 people lost their lives in the fire and approximately 65 hotel guests were injured; about 120 of the 304 registered guests that evening escaped unharmed. City of Atlanta health department investigators determined that 48 victims died of burns, 40 were asphyxiated by smoke and fumes, and 31 died as a result of injuries from jumping or falling from upper floors. Thirty-nine were under 20 years old. 105 were visitors to the city. Included in the fatalities were thirty teenagers in town for the Youth Assembly mock legislative session at the Georgia State Capitol. The original owner who had built the hotel in 1912-13, W. F. Winecoff (by then 85 and retired) and his wife, who occupied an apartment in the hotel, died in the blaze.

The Winecoff Hotel fully engulfed, December 7, 1946 |

----------------------------------------

"The serious losses in life and property resulting annually from fires cause me deep concern. I am sure that such unnecessary waste can be reduced. The substantial progress made in the science of fire prevention and fire protection in this country during the past forty years convinces me that the means are available for limiting this unnecessary destruction."

President Harry S. Truman

1947

We have mentioned several times in this series that the regulation of fire safety tends to occur at the local level. That fact was underscored by a 1945 survey of 3,322 municipalities by the National Bureau of Standards which found that:

- 236 had codes dated from 1942 to 1946.

- 387 had codes dated from 1937 to 1941.

- 228 had codes dated from 1932 to 1936.

- 484 had codes dated from 1927 to 1931.

- 612 had codes over 20 years old.

- 33 had codes with no dates.

- 1,342 had no building codes.

The President’s Conference on FIRE PREVENTION: Report of the Committee on Building Construction, Operation, and Protection

While the regulation of fire protection was to remain local, the fires of 1946 sparked an extensive and urgent re-evaluation of fire codes. The resulting strengthening of regulations varied from locality to locality, but in many municipalities nationwide, significant changes in codes took place. While already required in some places, sprinklers, lacking in all of the hotels that burned that year, were now mandated in many cities nation-wide. Fire doors of non-combustible materials were required, and required to be kept closed at all times. Transoms above guest room doors and fire doors were prohibited. Fire alarms and fire escapes were mandated.

Another area where the fires that devastated the four hotels in 1946 drove regulations was the issue of exits, insuring they were adequate in quantity and well-marked. The National Fire Protection Association had published and periodically updated its Life Safety Code since 1913, but following the tragic fires of 1946 the NFPA found its updated Building Exits Code -- at that time still aimed at builders rather than public safety officials -- was now being adapted by municipalities and other code authorities as legal building code. In response, the organization re-wrote its code over the next several years with an eye to its new role as a model regulation rather than recommendation for architects and contractors. Today, the voluntary, model code maintained by the National Fire Protection Association is adopted in whole or in part by many cities, counties and states nationwide.

The role of wall and floor coverings, decorations, and furnishings in the speed of the spread of fire and the production of toxic smoke and fumes in the hotel conflagrations of 1946, as well as the 1942 Cocoanut Grove fire exposed the need for a concrete method of evaluating the spread rate and smoke production properties of various building materials. In response to the tragedies, a new system of evaluating and standards of grading such materials was developed.

...by the mid-1940s, a number of disastrous fires occurred, including the Cocoanut Grove nightclub fire in Boston in 1942 and the Chicago LaSalle Street Hotel and Atlanta Winecoff Hotel fires, both in 1946. In all, 670 people perished in these three fires alone. The magnitude of the fire fatalities in each of these fires was directly related to the rapid flame spread and smoke development of the interior finish materials. These findings highlighted the need to test and classify materials on a scale that would measure the three essential material characteristics previously identified: flame spread, fuel contributed, and smoke developed. All these factors led to the evolution of the current tunnel apparatus. It was at this time that the Surface-Burning Characteristics Classification Scale was first defined.

Fire Protection Engineering: Assessing the Burning Characteristics of Interior Finish Material

-----------------------------------------------

The hotel fires of 1946 attracted the attention of more than just municipal officials and fire safety experts. President Harry Truman, who during 1946 had initiated a landmark conference on traffic and automobile safety, responded to the 1946 hotel tragedies by calling for a presidential conference on fire safety. 2,000 delegates would draw up national policies and plans for reducing fire risk to be held in May of 1947.

NATIONAL CONFERENCE ON FIRE PREVENTION

For more than a decade the loss of property in the United States due to fires has been steadily mounting year by year. During this period an average of 10,000 persons have been burned to death or have died of burns annually. In the first nine months of this year fire losses reached the total of nearly half a billion dollars, with the prospect that final reports for 1946 will show this year to have been the most disastrous in our history with respect to fire losses.

[...]

The President has, therefore, decide to call a National Conference on Fire Prevention, to be held in Washington within the next few months, to bring the ever-present danger from fire home to all our people, and to devise additional methods to intensify the work of fire prevention in every town and city in the Nation.

As if to put an exclamation mark on the urgency of the conference, one month before the event was to get underway a ship loaded with ammonium nitrate fertilizer caught fire and exploded at the docks in Texas City, Texas, sparking a fire that burned businesses, refineries, and over 500 homes with a toll of more than 580 killed and 5,000 injured.

President Truman himself participated in the conference which brought together a Who's Who of movers and shakers in all walks of public life to develop a plan of action to reduce losses from fire. The conference was a wide-ranging affair, addressing building design, construction methods and materials; on-site fire-fighting equipment and training; sprinklers and other built-in fire-suppression equipment; alarm systems; modernization of fire codes; properly equipping fire departments, training of both firefighters and the public; the adequacy of public water-delivery systems; and a number of other topics. It made the following recommendations on regulation:

E. PUBLIC REGULATION

Although the American public cries out against "regimentation" and cherishes freedom of action, the pursuit of selfish freedom has been an important factor in our economic fire waste and mounting loss of life.

Our fire losses have long since been recognized as a national problem, and the adoption of more severe regulations, as well as their proper enforcement, is therefore unavoidable if the welfare of the public is to be safeguarded.

Any comprehensive study of present conditions will reveal the difficulties involved in preparing laws and regulations to cope with the situation. As will be described in this report, of those codes and standards which have thus far been adopted, too many are obsolete, too many are subjective to evasions, and uniformity is lacking.

There is need for the adoption, through enabling legislation, of uniform building codes, regulations, and fire prevention ordinances that will establish requirements for safety of operations and proper maintenance of structures and of their service and fire protective equipment. The enabling legislation should provide for the proper adoption, by reference, of recognized national standards.

Codes and ordinances are of limited value unless they embrace adequate power to enforce compliance, including the right of retroactive action for the correction of certain conditions found especially dangerous to the occupants or detrimental to the public welfare, and unless there is an adequate staff to enforce them.

Governmental authority should be empowered by law to examine, approve, and regulate operations and changes in occupancy or use of buildings, with provisions for inspection by competent fire prevention and protection experts. The infliction of penalties may be necessary to effect corrective measures.

The requirement of annual licenses for places of public assembly, supported by inspection service, is an effective means for the control of operations to prevent abuses in fire safety matters.

Safety of life and limb is so compelling a consideration that inconvenience and expense are not sufficient reasons for failing to take reasonable measures that will bring buildings up to modern standards.

The possible loss of buildings that provide shelter and the means of livelihood for many people is another powerful reason why action should be taken in the public interest.

Pending complete or extensive code revision, which it is recognized is a time-consuming process, consideration should be given to immediate adoption of what might be termed emergency legislation dealing with the correction of deficiencies in existing buildings.

The President’s Conference on FIRE PREVENTION Report of the Committee on Building Construction, Operation, and Protection (.doc)

The very first item in the above block quote proved prophetic. The Truman administration's unprecedented government take-over of fire safety was thwarted and the conference saw its most ambitious proposals mostly rejected; the report the conference produced has been so forgotten over the years that until the document was recently made available on-line on the United States Fire Administration website, only one complete copy of the report was known to exist.

Of the report, the USFA says:

...Further, that something of the magnitude and importance of the '47 report, which hasn't been a routine part of fire science and fire technology community college teachings, nor otherwise discussed for decades in fire safety circles, remains so unknown, is surprising.

[...]

The '47 Report has not been mentioned in major fire protection writings of the last 40+ years either. Perhaps, each generation has to "reinvent the wheel," so to speak, but all who read it today are amazed by its contents and most who get to see it say they couldn't put it down until finished reviewing it.

United States Fire Administration: 1947 Fire Prevention Conference

While the 1947 conference and its report were destined to be largely forgotten, a number of topics covered at the conference, in that they reflected contemporary debates and discussions in the public policy arena, did ultimately come to bear on the development of fire safety and regulatory policy. One of the most important examples, hinted at above, is a section of the report titled "Applying New Fire Prevention Regulations to Existing Buildings", where the conference examined what was called the 'vested rights' argument, "contending that a building owner, by erecting his structure in compliance with the existing building code regulations, is not subject to the application of new fire prevention regulations, [...] that application of new fire prevention regulations to such buildings is retroactive in effect ."

For decades a dispute had simmered between municipal officials and public safety advocates over the government's authority to mandate compliance to current fire safety regulations in buildings built under a prior code. The 1946 tragedies brought about a fundamental re-assessment of that dispute.

As the Iroquois had done for theaters and Our Lady of the Angels was soon to do for schools, the Winecoff reignited a debate that had been smoldering for decades among fire safety professionals and municipal government officials: could a municipality legally enforce current codes on structures built under an older code? City attorneys argued that this would be an unconstitutional ex post facto law; fire safety experts argued that the government not only had the right but the responsibility to protect its constituents from obviously mortal danger as part of its police power. After the Winecoff and the Cocoanut Grove, fire safety won the argument for retroactive enforcement of building codes in public-assembly occupancies in most urban jurisdictions. It was the last triple-digit-mortality hotel fire in United States history.

Rachel Maines, Asbestos and fire: technological trade-offs and the body at risk

In the wake of the fires of 1946 and the enormity of the 209 lives lost in the well-publicized horrors, the will to oppose such regulation crumbled in the face of public opinion, and the interest of the government in protecting public safety prevailed.

-----------------------------------

I'll leave you now with one last, little take-away from the fires at the LaSalle, Canfield, Baker, and Winecoff. The next time you're in a hotel, take a look at the inside of the door to your room. Chances are you'll see something like this:

Contemplate it, study it, commit it to memory-- and remember the 209 souls who died to put it there, another regulation that came to be as a result of the hotel fires of 1946.

----------------------------------------------

And that, dear Kossacks, is where regulation comes from -- not from some bored bureaucrat sitting in an office in Washington trying to think up ways to make life miserable and expensive for some innocent and unsuspecting businessman, but from real human suffering and tragedy brought about, all too often, by people who shirk what should be obvious responsibilities, who neglect basic diligence, who sacrifice safety for profit. They bring suffering on those who trust them and their products, and society adopts measures to make sure it never happens again. We have to force them, through regulation, to behave as they should have been behaving all along. That's how regulation come to be.

----------------------------------------------

Previous installments of How Regulation came to be: