As some Kossacks know, I normally write diaries about issues that concern the National Wildlife Refuge System, and one issue that has fallen under the radar lately is the impact that the border wall is having on communities, wildlife, and vital habitat along the US/Mexico border.

Homeland Security Secretary Michael Chertoff waived as many as 19 American laws in order to rush the building of the wall, and several conservation groups are now working together to minimize the damage.

The International League of Conservation Photographers is currently using a team of photographers, writers, filmmakers, and scientists to document the wildlife, landscapes and human communities of the US/Mexico borderlands, and the impact that the border wall is having on them.

The ILCP is currently down along the border, and they have started a blog to document their experiences. Eventually they will use their images for a photo exhibit on Capitol Hill, and they also plan to hold a congressional briefing where they will show a multimedia movie from the expedition. All of this will be coordinated with legislative work being conducted by Rep. Raul Grijalva (a great supporter of our public lands), and lobbying efforts by the Sierra Club, Defenders of Wildlife and others.

According to the ILCP, their goals include

- To end or revoke the authority that Congress gave the Department of Homeland Security to waive all laws to expedite building of the wall. This waiver has resulted in the unilateral dismissal of dozens of environmental laws, including the Endangered Species Act and Clean Air Act.

- To mandate that environmental damage from wall that has already been built, be addressed and mitigated.

- And finally, to encourage increased international cooperation on borderlands ecological issues and migration corridors.

With the permission of the ILCP, I'm sharing some excerpts from their blog entries, which record their experiences at the border over the last couple weeks:

January 25:

In San Diego, over the past two days we have seen Smugglers Gulch, a valley in the coastal hills shared by both border towns, filled with an incomprehensible volume of dirt, in order to facilitate the building of more layers of wall. What was the gulch drains into the Tijuana estuary, a Wetlands of International Importance, as designated by the RAMSAR Treaty. And ecologists here believe the sediment runoff from this massive construction project could doom this rare estuary, a place filled with life and a quiet respite for the people of the region.

We have also visited the Otay Mountain Wilderness, a designated wilderness that the Department of Homeland Security is now using for a staging ground for wall construction, cutting scars of roads in a landscape that was only a month ago a haven for wildlife and people.

January 26:

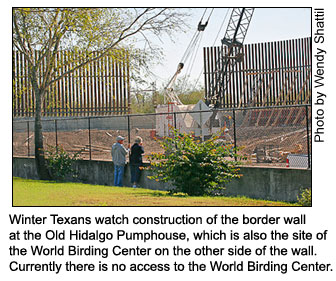

Some living near the Rio Grande are grateful for the hard work of the border patrol and the promise of the wall to halt the unending flow of immigrants past their homes. Others see the artificial barrier in a broader picture of environmental damage and an expensively wrong-minded attempt to stop a flood by putting a few rocks in its path. To them, there is already a border wall and it's called the Rio Grande.

As debates go on, bulldozers, cranes and laborers create imposing barriers and nature does her best to adapt. Limited populations of sabal palm and ocelots share a struggle to maintain a foothold near the bottom of the Rio Grande as habitat is encroached upon. Mammals, reptiles and amphibians are blocked in their movement to food, water and shelter. Riparian corridors are severed, requiring some to cross paths with humans, dogs and highways.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has been mandated for 30 years to restore and maintain the wildlife corridor along the Lower Rio Grande. 100 million dollars of government money has been invested and countless staff and volunteers have dedicated themselves to the effort with admirable results, adding pearls along a string with the ultimate goal a complete necklace of a riparian corridor from Falcon Dam to the Gulf of Mexico. At a cost of 3.9 million for construction of each mile of the border wall, conservationists see a reversal of 30 years' work.

January 26:

We traveled East along Highway 2 in Mexico. To the left of the road, the wall is a continuous solid metal barrier 4 meters high. I cannot imagine the cost of setting it up, but can think of many better uses for such an amount of money. We also wondered how effective it is to stop the people, as we see, every few kilometers, improvised ladders to jump the fence, but walking along side it, we see no gaps and no burrows that could allow, even a small walking critter, to cross the border.

January 27:

For all desert animals, getting to water sources they have trusted for millennia means the difference between life and death. Animals just south of the wall, particularly pronghorn, bighorn and cats, may have used the Tinajas Altas high tanks or Tule well which sit just a few miles north of the border. But with a 15 foot barrier blocking their movements, they will have to seek out water elsewhere - and in the desert, a search for water can just as easily end in death as in a life-saving drink.

February 2:

Over the past year, this last free flowing river in Arizona, one of the last in the southwest and a critical haven for wildlife, has been the site of massive construction. In January 2008, the Department of Homeland Security pulled its legal trump card and waived the laws a court judge had used to issue a temporary restraining order against construction. From that moment, the DHS began to build a stretch of dozens of miles of impermeable steel wall leading right to the edge of the river from the east and west side.

I was here in summer and fall 2008 and saw the progression of it. In the mornings last summer I saw javelina and jackrabbits at the wall, pacing back and forth before giving up and heading back into the brush. I saw bobcat and deer tracks following the base of the wall and then veering off...

These people have seen what so many have said, including the Secretary of the Department of Homeland Security, Michael Chertoff: The wall will not stop people...

And importantly, given all the input that was available from science, local people and simple observation, had things been different, our environmental laws could have required DHS to listen. But all bets are off in a world where government no longer has to listen to its own laws.

Visit the website for the International League of Conservation Photographers, and be sure to let your representatives and senators know that you have not forgotten about the wall or its impact on human communities, wildlife, and vital habitat.