About twenty-five miles upriver of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, the Monongahela River makes a sweeping horseshoe bend. Nestled in the horseshoe on the west bank or the river is the town of Donora, surrounded by a ring of 400-foot-tall hills and river bluffs that form a bowl around the town.

Bowls are made to hold things. For five suffocating days at the end of October, 1948, the topological bowl around Donora did just that.

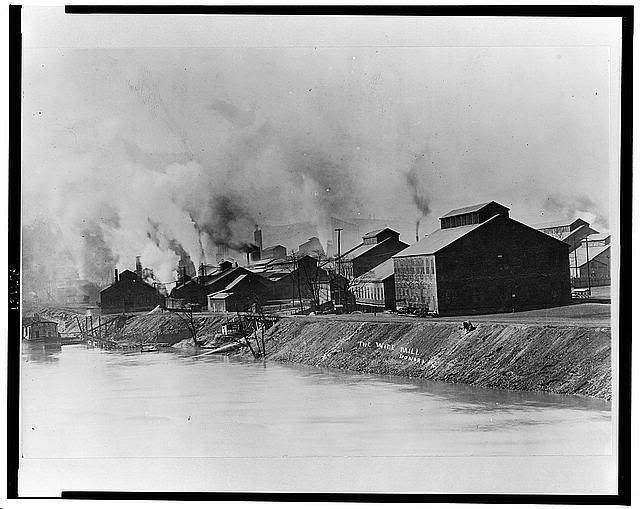

The U.S. Steel Corporation's Donora Zinc Works and its American Steel & Wire plant employed thousands of Monongahela Valley residents, bringing good jobs and comfortable incomes to the local population. In exchange, the residents of Donora and surrounding towns were willing to live with the yellow clouds laden with sulfur dioxide and other contaminants that belched from the plants. As a veteran of the disaster, Bill Schempp, said years later, "That's the way it was here. It was a normal way of life."

Residents didn't show much concern when a thick fog rolled in on October 26, 1948, trapping pollutants from the mills in it, and they found themselves immersed in the foul yellow cloud. Given the bowl-like topology around the town, it wasn't unusual for temperature inversions to trap the smog in the valley for a few hours, even a day or two. But this smog just would not go away.

Smog laden with sulfur dioxide from the zinc works was something Donora residents had become used to. As it thickened, residents went about their normal routines. On Oct. 29, the smog hid players from the crowd at a high school football game, and later, it became too thick to drive. That evening, people walking outside couldn't see their hands in front of their faces.

Still, few had any sense of the danger encircling them.

CLEANER AIR IS LEGACY LEFT BY DONORA'S KILLER 1948 SMOG

This time the smog had not broken up in a few hours. One day turned into two and still the thick cloud remained. Then a third day. And a fourth. And as the crisis dragged on, people began to die.

-------------------------------------------

The toxic effects of the smoke and fumes emitted from the zinc works had been recognized long before the 1948 tragedy.

Air pollution problems at the zinc works were recognized as early as 1918, when the plant owner paid legal claims for pollution that affected the health of nearby residents.

In the 1920s, residents and farmers in nearby Webster filed suit against the company for killing crops and livestock. As a result, air sampling was conducted from 1929 through 1936. But until 1948, smoke was generally considered a hassle rather than a health threat.

ibid.

Mrs. Lois Bainbridge, in a letter to Governor James T. Duff following the 1948 tragedy, related that area residents had complained for years about the industrial pollution that "eats the paint off your houses" and renders the river incapable of supporting aquatic life.

Indeed, an investigation supervised by the director of the state government's Bureau of Industrial Hygiene revealed an extraordinarily high level of sulfur dioxide, soluble sulphants, and fluorides in the air on October 30 and 31. According to the agency's report and complaints by residents, such contamination of the atmosphere was caused by the zinc smelting plant, steel mills' open hearth furnaces, a sulphuric acid plant, with slag dumps, coal burning steam locomotives, and river boats also contributing to the problem.

The Donora Smog Disaster, October 30-31, 1948

A Time magazine article from the time records that a man walking home in the smog began to experience difficulty breathing and was seized by a coughing fit. He sat down on the curb and shortly keeled over and died, the first casualty of the smog. Others soon followed, mostly the elderly and others suffering asthma and other respiratory and cardiac ailments. Hundreds flooded the local hospital and calls of people suffering respiratory distress swamped the emergency lines. Bill Schempp, a fireman at the time, recounted the effort to get relief to the townspeople.

When fire bells rang that evening, Schempp and other firemen learned that they were to take oxygen to residents struggling to breathe. Schempp said he had to feel his way along buildings and fences, go up the steps of each house and strain to make out the house number. Going several blocks took 45 minutes.

CLEANER AIR IS LEGACY LEFT BY DONORA'S KILLER 1948 SMOG

The city had only a limited supply of oxygen available, and although neighboring towns responded with assistance, the need far outstripped the available supply. Firemen were forced to allow the distressed just a few clean breaths of bottled oxygen before having to move on to the next victim, to the protests of his or her family. But there were others in need, and nowhere near enough oxygen to go around.

The first death occurred Friday. By Saturday the three funeral homes quickly had more corpses than they could handle. The town's eight physicians hurried from case to case, able to spend only a few minutes at each bedside. Pharmacists dispensed medications by the handful. The town set up a temporary morgue.

Yet the steel mill and the zinc works continued to operate, stacks steadily spewing more fumes into the loaded atmosphere...

Smithsonian.com: A Darkness in Donora

The town's Health Board approached the mill managers, requesting the mills suspend operation until weather conditions changed and the smog cleared, but they refused. As conditions worsened and more and more residents fell ill, a hotel was pressed into service, the upper level as a hospital, the lower as a morgue. The town's eight doctors were overwhelmed. Men on foot picked their way through the streets guiding ambulances to houses to pick up people in distress and corpses of the dead. Doctors and public officials recommended those at risk evacuate the town, but the foggy conditions made driving nearly impossible. Physician William Rongaus said in a 1995 interview. "People were dying while I was treating them. I called it murder from the mill."

As the deaths mounted and the toll of the sickened began to approach half the population of the town of 14,000, media began to pick up the story. Radio icon Walter Winchell, among others, publicized the plight of Donora and helped bring attention to the tragedy, although many other media were slow to pick up the story or treated it as routine and only marginally newsworthy. Smog was just the price one paid for industrialization.

Finally, at 6:00 a.m. on Sunday morning October 31, the U. S. Steel plants were shut down on orders from the parent company. Later that day a drizzly rain began to fall, washing the pollutants out of the air and ending the crisis. The next day, the plants resumed operation.

-------------------------------

In all, twenty people were killed. Estimates of those sickened by the smog range from 5,000 to 7,000. While Donora tried to put the disaster behind it, society was not so quick to close the book on the incident without drawing some lessons from it.

Soon after the smog dissipated, the state Department of Health, the United Steelworkers, Donora Borough Council and the U.S. Public Health Service launched investigations. It marked the first time that there was an organized effort to document health impacts of air pollution in the United States, Snyder noted in her paper.

The investigations prompted Public Health Service recommendations for a warning system tied to weather forecasts and air sampling. In 1955, the state passed the Clean Air Act, the first law to control air pollution, in direct response to Donora.

CLEANER AIR IS LEGACY LEFT BY DONORA'S KILLER 1948 SMOG

In 1949 Pennsylvania established the Division of Air Pollution Control to study ways to improve air quality. The 1955 state law was followed by a series of increasingly strict pollution control laws. In 1966 the state enacted more statewide clean air regulations, and in 1970 passed an "Environmental Bill of Rights" which stated that "the people have a right to clean air, [and] pure water...." The Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Resources (today the Department of Environmental Protection) was established "to ensure future generations of Commonwealth residents a quality environment." The rest of the nation also benefited from Donora's experience as laws were passed at the federal level as well. In 1950 President Truman convened the first nationwide clean air conference which, although it did not produce particularly drastic recommendations, laid the foundation for two decades of increasingly stringent regulations beginning with the Air Pollution Control Act of 1955, followed by the Clean Air Act of 1963, and culminating in the Clean Air Act amendments of 1970 and the formation of the Environmental Protection Agency the same year.

As a result of civic action, Americans could now see, smell and, in fact, taste the improvements in their air. They would not settle for less. And in 1963, Congress passed the first federal Clean Air Act, then amended it in 1970 to give it teeth. States were now required to come up with plans for reducing pollution to meet federal clean air standards.

Since the passage of the 1970 Clean Air Act, we have removed 98 percent of lead from the air, 79 percent of soot, 41 percent of sulfur dioxide, 28 percent of carbon monoxide, and 25 percent of the smog soup now called ozone.

DONORA DISASTER WAS CRUCIBLE FOR CLEAN AIR

-------------------------------------------------

The U. S. Steel Corporation zinc works closed in 1956. The steel and wire plant shut down a few years later. Today, it is illegal in the United States to discharge into the atmosphere the levels of chemicals that caused the Donora disaster. It is illegal because the public demanded that it be illegal.

Only about 6,000 residents remain in Donora today. No comparable industries have replaced the absent factories. Few of the kind of industrial processes that were carried out in Donora in 1948 are operating within the United States today. Those factories have been relocated "offshore", a part of the exodus of manufacturing jobs from the country. Today, to far too large an extent, the companies that produce those commodities, rather than producing them more cleanly and safely here, are simply creating new Donoras in third-world countries across the planet where desperately impoverished people accept deadly toxic smogs as the price of relative prosperity. As the largest consumer of the goods that are made in these factories, even though they are not produced here, those commodities are produced for us. Companies will continue to create new Donoras (or possibly Bhopals) so long as we allow it.

In the video below, Dr. Davis quotes Jared Diamond, as saying, "Tragic sins become moral failures only if we should have known better from the outset." Today, we know the consequences of the kind of pollution that went on in Donora leading up to 1948, but we continue to allow it. Just not here.

---------------------------------------------------------

Video of a speech by Dr. Devra Davis, an epidemiologist, director of the Center for Environmental Oncology of the University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute, and author of When Smoke Ran Like Water: Tales Of Environmental Deception And The Battle Against Pollution , who was raised in Donora, at the opening of the Donora Smog Museum:

-------------------------------------------------------

In part 2 of the "Radium Girls" installments of this series, I quoted Florence Kelley, the first Executive Secretary of the National Consumers' League:

To live means to buy.

To buy means to have power.

To have power means to have responsibility.

The United States, with less than 5 percent of the world's population, consumes 30% of its resources. While that represents a grossly unbalanced degree of consumption, it also constitutes a tremendous amount of power -- and responsibility. We can make cleaner production happen world-wide simply because we, as the largest consumer nation, demand it. We need only the will to apply the power we hold.

-----------------------------------------------------------

So that, dear Kossacks, is where regulation comes from, not from some bored bureaucrat sitting in an office in Washington trying to think up ways to make life miserable and expensive for some innocent and unsuspecting businessman, but from real human suffering and tragedy brought about, all too often, by people who shirk what should be obvious responsibilities, who neglect basic diligence, who sacrifice safety for profit. They bring suffering on those who trust them, and society adopts measures to make sure it never happens again. We have to force them, through regulation, to behave as they should have been behaving all along. That's how Regulation came to be.

-------------------------------------------------------------

Previous installments of How Regulation came to be:

How Regulation came to be: 1938 Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act

How Regulation came to be: The Iroquois Theater Fire

How Regulation came to be: Radium Girls - Part I

How Regulation came to be: Radium Girls - Part II

How Regulation came to be: Radium Girls - Part III

How Regulation came to be: Construction Summer

How Regulation came to be: Red Moon Rising

How Regulation came to be: The Cherry Mine Disaster, Part I

How Regulation came to be: The Cherry Mine Disaster, Part II

How Regulation came to be: Ground Fault, Interrupted

How Regulation came to be: The Cocoanut Grove

-------------------------------------

If you are interested in environmental issues, please join DK GreenRoots, a new environmental advocacy group created by Meteor Blades. DK GreenRoots is comprised of bloggers at Daily Kos and eco-advocates from other sites. We focus on a broad range of issues. We alert each other to important eco-stories in the mainstream media and on the Internet, promote bloggers at one site to readers at other sites and discuss crucial eco-issues. We are in exciting times now because for the first time in years, significant environmental legislation will be passed by Congress. DK GreenRoots can also be used to apprise members of discussions and strategy sessions happening in Meteor Blade’s Green Diary Rescue thread, which is also our workroom. |