Commentary by Deoliver47, Black Kos Editor

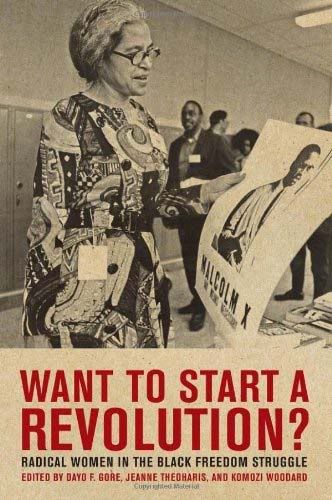

Want to Start A Revolution? Radical Women in the Black Freedom Struggle

I had planned to write about Lena Horne, when I heard of her passing but this diary: Lena Horne Dead at 92 was a fitting tribute to her life, and work. She was not simply a songstress, or actress; more important was her lifelong commitment to activism, which many readers learned about for the first time. Rest in peace, strong, elegant Lady Lena.

Her death, and the poem selected for today by Justice Putnam, got me to thinking about other women I've known, or looked up to, or been inspired by. Some of them have been written about in previous Black Kos diaries; Fannie Lou Hamer, Ella Baker, Audre Lorde, and Bernice Johnson Reagon.

Many of us are familiar with male leadership, and male organizers from the Civil Rights movement. Less attention has been paid to the role of women in the movement. Each semester in my women's studies classes, I find that few students can name more than one or two; if that.

Along those lines I'd like to bring to your attention a recently published book, "Want to Start A Revolution? Radical Women in the Black Freedom Struggle", edited by Dayo Gore, Jeanne Theoharis and Komozi Woodard, and published by New York University Press. Some of the women covered are sisters I knew, some were my compañeras in struggle, others were mentors or role models. I am honored to have been included among them.

Reviewer Ernesto Aguilar writes:

The position of women as organizers seems under continuous scrutiny. For women of color, the clashes they face are compounded by questions of loyalty as well as privilege and struggling within communities that have been subjected to historic miseducation and troubles. A new work offers a lively picture of two dozen different women organizers and how their contributions define our present and, possibly, our future.

Want to Start A Revolution? Radical Women in the Black Freedom Struggle presents the work and thinking of dynamic women organizers, some you may know and others whose labors are not as remembered. The diverse collection, edited by Dayo Gore, Jeanne Theoharis and Komozi Woodard, tells a story of fluid political organizing that universally crossed the boundaries of traditional activism. Whether it was the Black Arts Movement or Black Panther schools, the women profiled in Want to Start A Revolution? gave life to movements. Today, their work can teach new activists about seeing struggles not merely in mechanical ways, but in forms that see the conflicts of the world as intersecting capital, education, work, socialization and norms, and ways women have organized to confront oppression and forecast visions of liberation.

It is a special work that can present a full chapter on activists like Vicki Garvin, the late former Communist Party activist turned globetrotting internationalist whose stays include time in China and postcolonial Ghana. Whereas Garvin got a passing mention in Freedom Dreams: The Black Radical Imagination, Robin D.G. Kelley’s sublime investigation of Black leftism, her motivations and life are here searched. Much can be said as well of Shirley Du Bois, Esther Cooper Jackson, Florynce Kennedy and Johnnie Tillmon, to whom following chapters are devoted. The editors do well to avoid triumphant revisions of history in all cases. The hardships Kennedy faced, the pain of hopes dashed by a military coup in Ghana, and most evidently, the sexism and chauvinism they endured are laid bare. The book is at points a stomach-churning read, but is instructive as collection of how women have succeeded as organizers and how movements evolve.

After an introduction by the editors, contributions by a diverse group of scholars and activists cover these contents:

"No Small Amount of Change Could Do" Esther Cooper Jackson and the Making of of a Black Left Feminist by Erik S. McDuffie.

What "the Cause" Needs Is a "Brainy and Energetic Woman": A Study of Female Charismatic Leadership in Baltimore,by Prudence Cumberbatch.

From Communist Politics to Black Power: The Visionary Politics and Transnational Solidarities of Victoria "Vicki" Ama Garvin, by Dayo F. Gore

Shirley Graham Du Bois: Portrait of the Black Woman Artist as a Revolutionary by Gerald Horne and Margaret Stevens

"A Life History of Being Rebellious" The Radicalism of Rosa Parks by Jeanne Theoharis

Framing the Panther: Assata Shakur and Black Female Agency, by Joy James

Revolutionary Women, Revolutionary Education: The Black Panther Party’s Oakland Community School by Ericka Huggins and Angela D. LeBlanc-Ernest

Must Revolution Be a Family Affair? Revisiting The Black Woman by Margo Natalie Crawford

Retraining the Heartworks: Women in Atlanta’s Black Arts Movement by James Smethurst

"Women’s Liberation or . . . Black Liberation, You’re Fighting the Same Enemies": Florynce Kennedy, Black Power, and Feminism by Sherie M. Randolph

To Make That Someday Come: Shirley Chisholm’s Radical Politics of Possibility by Joshua Guild

Denise Oliver and the Young Lords Party: Stretching the Political Boundaries of Struggle by Johanna Fernández

Grassroots Leadership and Afro-Asian Solidarities: Yuri Kochiyama’s Humanizing Radicalism by Diane C. Fujino

"We Do Whatever Becomes Necessary": Johnnie Tillmon, Welfare Rights, and Black Power, by Premilla Nadasen

Feminist Reviewwrites:

Can African American liberation be understood without easy binaries: nonviolent civil disobedience vs. armed self-defense, integration vs. Black nationalism, MLK vs. Malcolm X? Can the history of feminism be written without effacing the contributions of Black feminists and other people of color? As Want to Start a Revolution? shows, foregrounding the work of women in Black liberation immediately problematizes these simple classifications. The cover photo of Rosa Parks admiring a poster of Malcolm X is, as the editors write, "an essay in and of itself." Although commonly associated with the Montgomery bus boycott and Martin Luther King, Jr., Parks supported both King and Malcolm, and her activism spanned decades before and after Montgomery.

By profiling several different activists in a series of fourteen essays, Want to Start a Revolution? builds a complex and fluid picture of Black women's activism. These women stood at the intersection of racial, sexual, and class oppression, and often devoted themselves to working on all three fronts. A chapter on Johnnie Tillmon and the welfare rights movement explores this theme of poor Black women's triple exploitation, and Esther Cooper Jackson, the subject of the first chapter, directly addressed this triad in her 1940 thesis, "The Negro Woman Domestic Worker in Relation to Trade Unionism."

The editors set the goal of avoiding "dominance through mentioning," historiography that acknowledges the contributions of women and the relevance of feminism without offering serious consideration. On that goal, this book must be judged a success. We get history from the Black female point of view, and encounter famous Black men only through their associations with women of color, such as Cooper Jackson, Parks, and Yuri Kochiyama.

Meet some of the women whose lives and activism are covered in the book.

Johnnie Tillmon

Johnnie Tillmon began her work as a leading activist for poor women in 1963, when she helped to found ANC Mothers Anonymous of Watts, the first grass roots welfare mothers organization in the country. She played key roles in the later formation of both the California Welfare Rights Organization (CRWO) and the National Welfare Rights Organization (NWRO), and eventually became executive director of NWRO. The eldest of three children, Tillmon was born in Scott, Arkansas. Her family were sharecroppers and she recalls picking cotton when she was only seven years old. She moved in with her aunt in Little Rock in order to attend high school, and during the war worked the night shift in a local munitions factory and attended school by day. At war's end, she quit high school and went to work in a laundry, where she engaged in her first organizing experience.

Tillmon continued to work in that non-segregated laundry for fifteen years until moving to California, by which time she was the single parent of six children. Trying to deal with her daughter's truancy, she decided to remain at home to supervise her children and applied for public assistance. She mobilized other women in the Nickerson Gardens Housing Project and after an initial meeting, they organized the ANC Mothers Anonymous of Watts. Several years later, she was elected to the newly formed LA County Welfare Rights Organization and then to the presidency of the CWRO. In 1967, she was elected to the NWRO.

In 1971, Tillmon moved to Washington, DC to become Associate Director of NWRO and following George Wiley's resignation in 1972 , she became Executive Director. This is also the year that she published her now famous article in Ms, "Welfare is a Woman's Issue." When NWRO closed its doors in 1974, Tillmon returned to Los Angeles, were she resumed her local community organizing. She remained active in the Watts community and continued to respond to phone queries from welfare recipients until 1991, when diabetes caused her health to fail.

Esther Cooper Jackson (link to 12 minute video)

came to New York City in 1952 after graduating from Oberlin College (1938) and Fisk University with a Masters degree in sociology (1940) and 7 years as a staff member of the Voting Project for the Southern Negro Youth Congress (SYNC) in Birmingham Alabama. SNYC registered voters and fought for equal housing and employment opportunities. Jackson was Executive Secretary of SYNC from 1942-46. Later she was the cofounder (with Shirley Graham Du Bois, W.E.B. Du Bois, and Louis E. Burnham) and managing editor of Freedomways - an influential African-American political and cultural quarterly (1961-1986) that featured early literary and political writings by luminaries from W.E.B. Du Bois, Martin Luther King, Paul Robeson, Alice Walker, Lorraine Hansberry, and James Baldwin. Artists in the magazine with cover art by such major artists as Jacob Laurence, Romare Beardon, and Elizabeth Catlett. For the 25 years of its publication, it was an important link between the northern and southern movements for civil rights - with both a national and international readership. It is also considered a precursor to the Black Arts movement in the 1960s and 1970s. She was also the co-editor of W.E.B. Du Bois: Black Titan and Paul Robeson: The Great Forerunner. She was married to influential political and labor activist James Jackson (1914-2007)

Toni Cade Bambara

photo credit: Susan J Ross, ©1994

Considered one of the best African American short story writers, her first collection, Gorilla, My Love, was published in 1972. She preferred to classify her writing as upbeat fiction. Most of the stories in Gorilla, My Love are told through a first-person point of view. The narrator (in many of the stories) is a sassy young girl who is tough, brave, and caring. These stories include "Blues Ain't No Mockin Bird" as well as "Raymond's Run." Active in the 1960s Black Arts and Black feminist movements, Bambara edited the 1970 anthology The Black Woman, a collection of poetry, short stories, and essays by such seminal writers as Nikki Giovanni, Audre Lorde, Alice Walker, and Paule Marshall, as well as Bambara herself. The anthology was extremely influential. She also wrote the introduction for the groundbreaking feminist anthology by women of color, This Bridge Called My Back (1981) edited by Gloria Anzaldúa and Cherríe Moraga.

In 1980, the first edition of her novel The Salt Eaters appeared in print. Her novel about the disappearance and murder of forty black children in Atlanta between 1979 and 1981, Those Bones Are Not My Child (originally entitled If Blessings Come), was published posthumously in 1999. The novel was edited by Toni Morrison, who regarded it as her masterpiece. Author/editor Toni Morrison gathered Bambara's short stories, essays, and interviews in a volume published by Vintage as Deep Sightings & Rescue Missions: Fiction: Essays & Conversations in 1996.

Her writing was strongly informed by radical politics, feminism, and African American culture. Bambara's works were often explicitly political, concerning themselves in general with injustice and oppression and in particular with the fate of African American communities and grassroots political organizations, as in The Salt Eaters, and The Bombing of Osage Avenue, which deals with the 1985 bombing of the MOVE headquarters in Philadelphia. Female protagonists and narrators dominate her writings. Bambara writes through African American cultural conventions, incorporating African American dialect, oral traditions, and jazz techniques. Other influences include the diverse Harlem community she grew up around as well as her principled and strong-willed mother, who urged her children to take pride in African American culture and history. Bambara produced many other significant works as well. She also contributed to PBS's American Experience documentary series with "Midnight Ramble": Oscar Micheaux and the Story of Race Movies. She also was one of four filmmakers who made the collaborative 1995 documentary W.E.B. Du Bois: A Biography in Four Voices.

A tribute to Toni, published after her death. It was painful for all of us who knew and loved her, to lose her so early in her journey.

In Praise of Toni Cade Bambara

Alice Lovelace

Atlanta, Georgia

Toni Cade Bambara, 56, a noted writer, editor and teacher, died of cancer at a hospital in Philadelphia. Toni left behind a legacy in her own work which includes short stories collected in Gorilla My Love, and The Sea Birds Are Still Alive and her novel, The Salt Eaters. She edited several anthologies of black writers and introduced their work to thousands of college students.

Toni's greatest gift to Atlanta was the time spent cultivating and nourishing new and emerging writers throughout Atlanta and Georgia. Between the famous potluck gatherings at her home and her work organizing writers and artists she made a great impact on the Atlanta arts community.

Thanks to Toni Cade Bambara, the Southern Collective of African American Writers was born and First World Writers was later birthed. Thanks to Toni Cade Bambara, writers from throughout this region, and especially African-American writers, are connected. Thanks to her role in the major 1984 Conference on Black Literature and Arts at Emory University, she continues to influence the focus of Southern literarature. Thanks to her capacity to share of herself and her knowledge, she has many sprouts and branches. I remember sitting around her kitchen waiting for the next spinach quiche to bake and listening to her stories. She taught us about the social responsibility of the artist.

Vicki Ama Garvin

From her obituary

Victoria H. Garvin, African-American liberation activist and dedicated internationalist, died at the age of 91 on June 11, 2007, after a long illness.

Vicki, as she was affectionately known, was born in Richmond, Virginia and grew up in a working class family in Harlem. Her mother was a domestic in rich white homes; her father a plasterer who often was unemployed due to racism in construction unions. Vicki spent her summers working in the garment industry to supplement her family's income.

From high school on, she became active in Black protest politics, supporting efforts by Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. to obtain better paying jobs for African-Americans in Harlem and creating Black history clubs dedicated to building library resources. After earning her B.A. in political science from Hunter College, she became the first African-American woman to earn a Master's degree in Economics from Smith College, and did graduate work in French literature. She spent World War II working for the National War Labor Board in New York, organizing a union there and serving as its President. When the wartime agencies ended, she became National Research Director of the United Office and Professional Workers of America and co-chair of its Fair Employment Practices Committee. During the postwar purges of the Left in the CIO, she was a strong voice of protest and a sharp critic of the CIO's failure to organize in the South.

She was married briefly to a trade union organizer, and although they divorced, she kept his last name. In 1951 she took part in the formation of the National Negro Labor Council (NNLC), and became a national Vice President and Executive Secretary of the New York City chapter. With the NNLC, she worked closely with Coleman Young, later Mayor of Cleveland, and she organized cultural programs featuring Paul Robeson, then under persecution. He was a close friend until his death. In 1955, under pressure from the House Un-American Activities Committee and other repression, the NCLC disbanded. In the wake of McCarthyism, Vicki traveled to Africa in the late 1950s, worked in Nigeria, and then went to Ghana, where she worked closely with Dr. W.E.B. DuBois and Shirley Graham DuBois, Alphaeus and Dorothy Hunton, and others on the African Encyclopedia and anti-colonialist efforts. In Ghana she lived with Maya Angelou and Alice Windom. When Malcolm X, whom she had known in Harlem, visited Africa, Vicki introduced Malcolm to the ambassadors from China, Cuba, and Algeria whom she knew from teaching English at their embassies. Using her French language skills, she interpreted for his meeting with the Algerians.

In 1964 Vicki was invited to China by the Chinese ambassador. Both Malcolm X and Dr. DuBois encouraged her to go. She taught English for six years in Shanghai. She became close friends with many of her young students and kept in touch with them over the years. In China, she also became close to then political exiles Robert F. Williams and Mabel Williams. When Mao Tse-Tung issued his proclamation in support of the Afro-American movement... She was an active supporter of many organizations, including: Sisters Against South African Apartheid/Sisters to Assist South Africa (SASAA); the Committee to Eliminate Media Offensive to African People (CEMOTAP); Black Workers for Justice; and the Center for Constitutional Rights.

Yuri Kochiyama

Democracy Now did an interesting piece on Yuri in 2008.

She is also the subject of a documentary film: Yuri Kochiyama: Passion for Justice

Yuri Kochiyama (born May 19, 1921) is a Japanese American human rights activist. Kochiyama was born Mary Yuriko Nakahara in San Pedro, California. After the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, Kochiyama's father was imprisoned the same day. Her family, sent to the Jerome War Relocation Center in Jerome, Arkansas, were among the 120,000 Japanese-Americans interned during the Second World War. Two of her brothers joined the U.S. Army. In 1960, Kochiyama and her husband Bill moved to Harlem, New York City, and joined the Harlem Parents Committee. She became acquainted with Malcolm X and became a member of his Organization of Afro-American Unity, following his departure from the Nation of Islam. She was present at his assassination on February 21, 1965 at the Audubon Ballroom in Harlem, and held him in her arms as he lay dying.

In 1977, Kochiyama joined the group of Puerto Ricans that took over the Statue of Liberty to draw attention to the struggle for Puerto Rican independence. Over the years, Kochiyama has dedicated herself to various causes, such as the rights of political prisoners, freeing Mumia Abu-Jamal, nuclear disarmament, and reparations to Japanese Americans who were interned during the war. In 2005, Kochiyama was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize through the "1,000 Women for the Nobel Peace Prize 2005" project.

I have fond memories of Yuri's apartment in Harlem, though she now lives on the West Coast, I smile each time I pass her former home in the projects. I can say honestly that I never went to a rally or a demonstration in NY - for black, latino, asian, or native american struggles where Yuri wasn't one of the first people there, and the last to leave.

She will always be one of my most honored elders.

Here's hoping you'll add this volume to your booklist. My apologies for not covering more here. I'll close with a quote from Yuri, on Justice:

"Our ultimate objective in learning about anything is to try to create and develop a more just society."

====================================================================

Today's News by dopper0189, Black Kos Managing Editor

====================================================================

====================================================================

It's a harsh reality for too many young black children. New York Times: Bloody Urban Landscapes

====================================================================

Driving through some of this city’s neighborhoods is like driving through an alternate, horrifying universe, a place where no one thinks it’s safe to be a child.

You follow a map in which the coordinates are laid out in blood. Over there, in front of that convenience store, is where Fred Couch, 16, was shot to death last December. The Couch boy went to the same school, Christian Fenger Academy, as Derrion Albert, an honor student who was beaten with wooden planks and kicked to death three months earlier in a broad daylight attack that was recorded on a cellphone by an onlooker.

Right there, on South Manistee Avenue, is where a 7-year-old girl riding her scooter was shot in the head and critically injured a few weeks ago.

=====================================================================

=====================================================================

Thank goodness for judicial review! New York Times: Uganda Panel Gives Setback to Antigay Bill

=====================================================================

A special committee organized by the president of Uganda has recommended that a harsh antihomosexuality bill that has drawn the ire of Western governments be withdrawn from Parliament, a senior government official said Saturday.

Adolf Mwesige, a lawmaker and chairman of the special committee, said that virtually all clauses in the legislation were either unconstitutional or redundant, and that any other clauses should be placed in another bill dealing generally with sexual offenses.

"Ninety-nine percent of all the proposals in the Bahati bill have been done before," Mr. Mwesige said. "If we proceeded, it would definitely provoke criticism, and rightly so."

The antihomosexuality bill, also known as the Bahati bill after David Bahati, the lawmaker who proposed it last year, has been widely criticized by human rights groups and foreign governments. It calls for homosexuals to be executed in some cases. It also says that homosexuals should be extradited and that people in Uganda must report anybody known to have committed a homosexual act within 24 hours. The bill found backing from a number of Uganda’s influential evangelical pastors, some of whom have been supported and partially financed by American churches.

=====================================================================

As a journalist who'd covered war, I got a kick out of rushing into danger. But would reporting on the earthquake hurt my unborn baby? Could I be a mother and a journalist, too? The Root: Pregnant and Covering the Crisis in Haiti

=====================================================================

Shortly after the earthquake, I stood in the open courtyard of a badly damaged downtown Port-au-Prince hospital in Haiti, in a makeshift maternity ward pushed outdoors by necessity, taking in the crying newborns and the laboring women moaning in pain. I scribbled in my notepad, taking detailed notes as I interviewed a Haitian-American nurse, a volunteer from New York. Dressed in blue scrubs, the nurse talked as she worked, pointing out what they had (bare-bones equipment) and ticking off a list of what they didn't have (lots and lots of medical supplies).

Suddenly, I felt three hard thumps in my belly. Surprised, I placed my right hand on my stomach.

"Are you pregnant?" the nurse asked.

I nodded yes.

"What are you doing here?" she said.

It was a natural question, one I had posed to myself throughout the 12 days I reported on the aftermath of the massive earthquake that struck Haiti on Jan. 12. I was, after all, nearly five months pregnant. Among the other questions I asked myself: Is the baby going to be OK? Am I crazy? And the one that filled me with a special dread: What kind of mother would willingly choose to bring their unborn child into a dangerous disaster zone?

=====================================================================

There is a popular African saying that "an attire is not complete until it is topped with a headgear". In West African nation Nigeria, headgear popularly known as "Gele" are synonymous with every woman and the culture. Africa News: Discovering Nigeria’s stylish headgears

=======================================================================

The "Gele" is a Yoruba word and it is a long piece of cloth that you tie and tuck on your head to create different looks.

"When a Man turns his head to take a second look at a woman, it is probably her Gele Headtie that got him hooked" is another popular saying in Nigeria. There are no two exact styles of Gele headwrap. Gele may look similar to the eyes, but on close examination, each Gele has its unique twists and turns creating an elegant look of an African woman.

======================================================================

This is a very frightening story! South African police have foiled an attempt by right-wing extremists to bomb black townships ahead of the World Cup, according to the country's police minister. Telegraph: South African police foil extremist attempt to bomb black townships.

=====================================================================

Police made several arrests in a number of areas and seized "caches of arms and ammunition, paraphernalia", said Nathi Mthethwa.

The minister declined to give details about how many people were arrested or their intended targets, but said some were believers in a white-only 'volkstaat'.

The arrests follow the killing of white supremacist Eugene Terreblanche last month. Mr Terreblanche, 69, was killed by two of his farm labourers, allegedly over a wage dispute. His death has inflamed race tensions within South Africa.

=====================================================================

African grandmothers have gathered in Swaziland to discuss the impact of HIV/Aids on their lives. BBC: Africa's grandmothers debate HIV/Aids

=====================================================================

Many have become the primary carers of their grandchildren after losing their own adult children to the disease.

Organisers say they hope to create a "solidarity movement" of African grandmothers to attract targeted aid.

More than 70% of the world's HIV/Aids sufferers are from sub-Saharan Africa and large parts of the population have been wiped out by the disease.

The inaugural African Grandmother Gathering has been organised jointly by Swaziland for Positive Living (Swapol), the Canadian-based Stephen Lewis Foundation and the Swazi government.

=====================================================================

Voices and Soul by Justice Putnam, Black Kos Tuesday's Chile, Poetry Contributor

One of the many benefits of living in the San Francisco Bay Area is being able to listen to the flagship Pacifica radio station, KPFA. Hard Knock Radio is a show on KPFA that interviews Hip Hop and Rap

artists weekdays at 4pm. This week's poet, Rocky Rivera was interviewed recently on Hard Knock Radio. My son, Israel Putnam/IzzyMaq (http://www.myspace.com/globalheatwreckordz) has had some

regional success in the Northwest with his Hip Hop/ RB stylings, so I like to think that I have developed an "ear" for Hip Hop that belies my generational Punk origins.

Rocky Rivera is the Hip Hop persona of a young Filipina who spends her time between Los Angeles and the SF Bay Area. Some statements from her Hard Knock Radio interview resonated with me. One in particular, about the origins and direction of Hip Hop/ Rap, stood out more prominently,

"It's not about being a gangster, it's about being a guerrilla. It's not about bling, it's about survival."

This week's poem; and yes, Hip Hop/ Rap is certainly poetry, pays homage to the Filipina revolutionary, Gabriella Silang, who was executed in 1763 after leading insurrectionists against the Spanish

Crown when her husband, Diego Silang was executed earlier that year; Black Panther, Angela Davis and the four school girls killed in the Birmingham church bombing; and United Farm Worker activist, Dolores Huerta.

Along the way, Rocky Rivera packs a lot of history, with a strong back-beat, into this poem/ song about strong women who changed the world, with power and...

Heart

Left him on a Tuesday

Found him on a Sunday

Cried when I saw my

Hankerchief in his suitcase

Letter folded neatly in his pocket

With my perfume

Knew that he was lying when he

Told me he’d be back soon...

I couldn’t sleep the night

He left me with a promise

That he’d always keep me close

When the struggle got the hardest

So I...wiped the tears

Tied the hankerchief around me

Rallied up the troops

So we could

Find the Spanish army

It was time to stop the cryin’

Time to start the fightin’

Love was the beginning

But my people steady dyin’

And so I promised him the same thing

Gabriela blast in the name of the Philippines

I could hear em in the back of my mind

They said "Please don’t break my heart"

It could only be a matter of time...

Studying overseas

When I heard about the blast

And I knew the little girls

Who were killed in Alabama

It was Carole, Addie Mae

Cynthia & Denise

The Klan got away

In cahoots with the police

Knew that it was coming

When the Panthers started forming

So I booked the first flight to the states

In the morning

To show them my solidarity

Tightened up my afro

Books in my hand

Revolution in my heart

So I used my education

To combat the injustice

It was more

Than Malcolm X and Martin Luther

In the trenches

Sistah soldiers put ya rifles up

Angela Davis ride when the Klan try to light us up

I could hear ‘em in the back of my mind

They said

"Please don’t break my heart"

It could only be a matter of time they said

It was modern day slavery

Livin’ in the Valley

Stockton, California

Pickin’ grapes with my family

And my people broke they backs

Just to make a couple bucks

While the whiteys in the town

Ridiculed us in they trucks

So I

Picked up the megaphone

Shouted to my people, El

Pueblo Unido

Jama Sera Vencido

...Told em to stick together

Demand to be treated equal

Otherwise

These fucking crackas

Will continue to abuse us

Threw me in the slammer

20 times and some change

Yeah they broke a couple ribs

But the spirit remains

Do it again in a heartbeat

Para mi gente

Dolores what they call me

-- Rocky Rivera

==================================================================

==================================================================

The Front Porch is now open. Grab a chair, set down and chat with us for a spell. If you are new, introduce yourself to the community.

Today's Front porch music is from Lena Horne: