Utah is not a place that immediately jumps to mind when the subject of coal fields comes up. But in the second half of the nineteenth century, finds in the mountains south of Salt Lake City led to a booming coal industry in the state. The small town of Scofield, in the mountains about a seventy miles south-southeast of Salt Lake City was a product of that boom.

Coal was discovered in the hills above Scofield in the mid-1870s. The town was founded in 1879, making it one of the first coal towns in the state. From 1879 to 1920, it was a booming center of mining, with a population of about 2,500 -- and 13 saloons. The mines at nearby Winter Quarters employed about 300 men.

Joe Hill (website): The Scofield Disaster

The story continues inside.

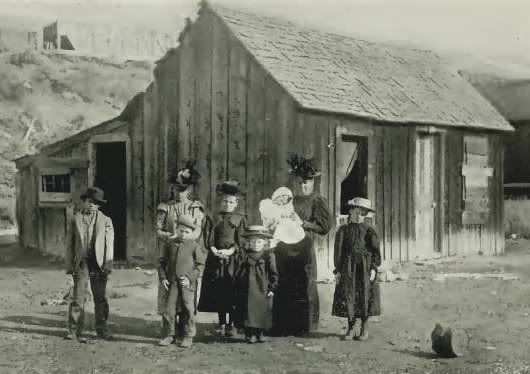

A miner's Shack in Scofield, Utah |

Despite the location in an area we don't think of as typical "coal country", the miners at the Pleasant Valley Coal Company's Winter Quarters Mines in Scofield, Utah, were exceedingly typical of the coal industry workforce at the turn of the twentieth century. They were largely recent immigrants, in the case of Scofield, predominantly Finnish, although Scots, Welsh, French, Italians, Danes, British, and even Icelanders were also represented. The majority had been in the country less than a decade Many had been recruited abroad by the mining companies, the companies sometimes paying their fare in exchange for a work agreement of a minimum duration. The immigrants lived in company houses, shopped at company stores, were often paid in company scrip, and frequently found themselves quickly in debt to their employers.

By 1900, five separate mines were operating at Winter Quarters, and with the new contract the Pleasant Valley Coal Company had recently landed to supply large quantities of coal to the U. S. Navy-- a contract that had prompted the company to boost the mines' production demands by 2,000 tons a day -- the town of Scofield had plenty to celebrate as Dewey Day approached.

The Scofield school's drum corps. |

If there was any resentment among the turn-of-the-century labor force about the co-opting of the traditional

May 1st labor holiday to honor the hero of the 1898 Battle of Manila in the recently concluded Spanish-American War, there is little evidence of it in contemporary accounts. There

were general strikes in Chicago in advance of the scheduled appearance of

Admiral George Dewey himself at the Windy City's celebration, but these appear to have been triggered by the use of non-union laborers by a contractor building one of the parade-review stands, and not, apparently, as a protest over the usurpation of the traditional labor day observed by workers in the rest of the world.

The town of Scofield had a gala celebration planned commencing at noon with fireworks and speeches, bands and music, and all manner of small-town revelry. Even the miners would be joining the crowd, as the mine was working only a half-shift that day, and shutting down at noon for the celebration. When townspeople heard a muffled, percussive "thump" about 10:30 am, most assumed it was just an ambitious celebrant getting a jump on the festivities with some early fireworks. Before long, though, word spread through the town. There had been an explosion at the mine.

What exactly happened deep inside Winter Quarters mine Number 4 that morning will never be known with any certainty; within seconds, anyone with first-hand knowledge of how the accident occurred was dead. Most speculation centers around blasting in the mine.

The mouth of the mine after the explosion. |

During the inquest, a miner named Andrew Smith blamed the explosion upon the Pleasant Valley Mining Company's practice of using "heavy shot" while the men were still underground. The state mine inspector agreed that coal dust played a role, but placed most of the blame on the company's stores of blasting powder. "I went to a place where it was claimed they had powder stowed away," Gomer Thomas explained, "and the place showed that the explosion had started here". Still, Thomas recommended that the company begin to water down the coal dust inside the Winter Quarters mine.

CR4: May 1, 1900 – The Winter Quarters Coal Mine Disaster

Inspector Thomas man have had ulterior motives in downplaying the possible role of coal dust in the explosion. He had inspected the mine just weeks before and had given it a clean bill despite dust in the mine (how much is open to dispute, the miners challenging the inspector's assertion of "little" accumulation). The inspector apparently subscribed to a belief that the dust was not prone to explosion due to absence of flammable gases. Like so many presumptions we've encountered in this series, that belief was, in an instant, proven abysmally mistaken.

The best guess is that miners working with a keg of "giant powder" accidentally set off a blast that exploded stores of blasting powder cached in the mine, which in turn kicked up clouds of coal dust that subsequently ignited in an explosion that engulfed practically the entire Number 4 main shaft.

The force of the blast was so great that it blew the bulk of the wooden structural supports out the mouth of the mine, demolishing the building that housed the winching mechanism that let cars down the incline into the mineshaft. The engineer who operated the apparatus was, serendipitously, away from his station and escaped serious injury from the blast. John Wilson, a 21-year-old mule driver who was standing at the mouth of the mine at the time of the explosion, was not as lucky

[W]e hastened to the mouth of the mine, where one horse was found dead but his driver could not be

seen until someone looking down the gulch saw the form of someone, supposed to be the driver, John Wilson. A few of the men hurried to his side and found that life was not yet extinct, although he had been blown eight hundred and twenty feet, by actual measurement - He was tenderly picked up and conveyed to his home where it was found that the back part of his skull had been crushed, besides a stick or splinter had been driven downward through his abdomen. He was in a critical condition and no one supposed he would live to be carried home, but, strange to relate, he has recovered rapidly and although he will never be able to do a day's work again he is up and feeling quite well at present.

J.W. Dilley: History of the Scofield mine disaster : A concise account of the incidents and scenes that took place at Scofield, Utah, May 1, 1900. When mine number four exploded, killing 200 men

Taken by train with four other severely injured men to a hospital in Salt Lake City, John Wilson recovered from his injuries, and although he was never able to work again, lived into his seventies. Other men working near the mouth of the mine also suffered severed injuries, including broken and crushed bones, dislocated joints, and internal injuries

Rubble of the mine entrance and remains of the hoist house. |

The rubble blown out of the shaft was so thick that it took rescuers twenty minutes to clear enough away to gain entrance to the mine. Attempting to reach any trapped miners through the Number One mine, which connected to Number 4 via an air shaft, the first would-be rescuers nearly became victims themselves as they encountered deadly

afterdamp, a mixture of poisonous gases -- principally carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, and nitrogen -- produced by the explosion and burning of the coal dust.

With the deadly gases settling into the lower levels of the Number One mine preventing access through that route, the rescuers were forced to wait until the rubble was cleared from the mine entrance at Number 4 and the residual fires from the coal dust explosion suppressed. As fresh air flowed into the shaft, the rescuers followed it down.

The first man encountered, so badly burned as to be unrecognizable, was at first mis-identified. His burns ultimately proved fatal, however, as he died during the night. A second man, William Boweter, was found alive but barely conscious, sitting amongst a pile of corpses, but with assistance, was able to walk out of the mine. These two proved to been the only men to be brought out of the Number 4 mine alive.

Roll after roll of canvas was brought, and brattices were fixed up on the inside to force the air into one level at a time in order that the rescuing party could force their way through the mine in the hope of finding someone still alive. But the farther the rescuers went the more apparent become the magnitude of the disaster. Men were piled in heaps as there were not enough men to carry out the dead as fast as found. The miners at Clear Creek mine by this time began to arrive, and their assistance came none

too soon, for there was plenty of work for all. The new arrivals began to carry out the bodies...

J.W. Dilley: History of the Scofield mine disaster : A concise account of the incidents and scenes that took place at Scofield, Utah, May 1, 1900. When mine number four exploded, killing 200 men

As hopes dimmed for any survivors in Number 4, rescue efforts turned to the Number One mine. Relatives of the miners working Number One presumed their loved ones would be safe from the disaster in Number 4. But the connecting air shaft proved fatal.

Thomas Pugh, who was only fifteen years old and working in the mine, seized his hat in his teeth and ran for the entrance of the No. 1 Mine, a mile and a half from his work area. He fainted when he reached it. Pugh's father, William, died at the place where Thomas began running. [...] After the explosion, Roderick Davis left the mine uninjured but was overcome by gas when he returned to the mine with a rescue party. Presumed dead by the rescue party, Davis was loaded into a mining car, but he revived when his body was being washed in preparation for burial.

Utah History to Go: Explosion of Pleasant Valley Coal Company

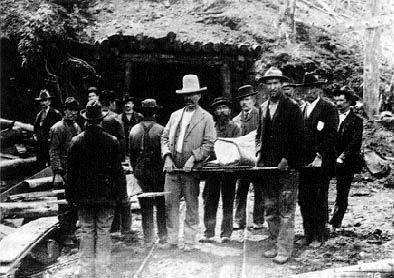

Bodies being brought out the entrance of Number One. |

Bodies were brought to the mouth of the Number One shaft in coal carts, as many as a dozen heaped in a car. Many were burned beyond recognition, many others overcome as the deadly afterdamp descended. One group of miners, uninjured in the initial explosions but uncertain of the location of the explosion, sought to escape the Number One mine by taking a shortcut through the connecting air shaft and following the shorter route to the surface through Number 4. They ran directly into the descending afterdamp. Many of them fathers and sons, uncles and nephews, they were found huddled together, their arms embracing each other as their miscalculation became apparent and the deadly gas overcame them.

The owner of Pleasant Valley Coal Company, in Salt Lake City when the explosion occurred, organized a train full of rescue workers and medical supplies. The train arrived in Scofield by 3:30 that afternoon, but there was nothing to be done but assist in the bring out of bodies.

Loading coffins delivered to the train station. |

There were not enough coffins in all of Utah to accommodate the dead of the Scofield mine; seventy-five had to be brought in from Denver to supplement the supply from Salt Lake City and other near-by cities. The death toll at Scofield was officially set at two hundred, but the exact number is hard to document. There was no record kept of who was working inside the mine at the time of the explosion. The miners themselves placed the count as high as 246.

Despite the assertion of news stories such as those in the Fort Wayne, Indiana Sentinel and the Brooklyn, New York Eagle the day after the tragedy that "nine tenths of the men killed are Americans and Welshmen," in fact, 61 are known to have been Finnish immigrants, and the toll of the dead produced the usual roster of predominantly-immigrant casualties. Twenty were young boys, less fortunate companions of the 15-year-old Thomas Pugh, above, whose mile-and-a-half race to the entrance of Number One saved his life. The 200 acknowledged dead left 107 widows and 270 fatherless children.

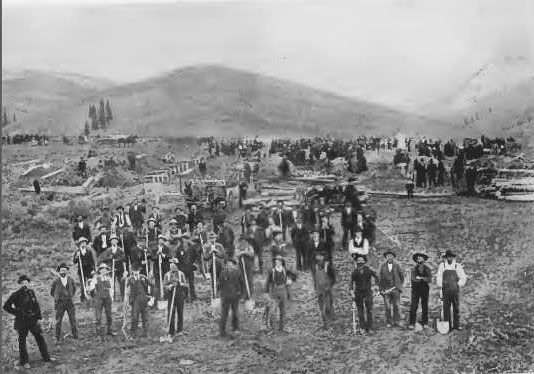

Boys from Provo, Utah, who volunteered to dig graves. |

The Pleasant Valley Coal Company provided each of the dead men with burial clothes and a coffin, and gave each man's family $500. The company also erased $8,000 in debt that the dead miners had accumulated at the company store. Other private donations came from a number of communities within and outside the state.

One hundred forty-nine of the dead were buried in the Scofield cemetery with two graveside services: one conducted in Finnish by A. Granholm, a Finnish Lutheran minister; and the second by LDS Church apostles George Teasdale, Reed Smoot, and Heber J. Grant. The other fifty-one victims were returned to their hometowns for burial.

Utah History Encyclopedia: Scofield Mine Disaster

The crowd at one of the funerals |

----------------------------------------------

In truth, there were really few immediate repercussions of Scofield in the regulatory arena. Outside Utah it had little impact; while it may have prompted mine inspectors in other states to direct closer scrutiny at the types of conditions believed to have led to the Scofield disaster, not many legally-enforceable changes came about because of the tragedy. And even within Utah the effects were mixed:

The Utah Legislature enacted stronger measures in 1901 in response to the Scofield disaster, including new rules for dust control, explosives, ventilation, and supervision. However, the new law also reduced fines, covered only large mines, and lacked effective enforcement.

Scott M. Matheson, Jr.: The State of Utah's Role in Coal Mine Safety: Federalism Considerations

.

On the other hand, the failure of the state and federal governments in the wake of Scofield to do much to protect workers from the unsafe conditions in the mines fueled a sense of outrage among the miners that led, the following year, to strikes centered in the coalfields around Scofield. A nationwide strike three years later led to the first attempts (although at first unsuccessful) to gain recognition of the United Mine Workers to represent the miners of Utah. Where the state failed to properly regulate the industry to protect its workers, the labor movement stepped into the vacuum to try to force proper observation of safety procedures as a component of labor agreements.

While the regulatory impact was disappointing, Scofield -- like movement caught in the corner of the eye during a walk in the woods -- did serve to draw attention to the conditions in the coalfields. And what the newly-engaged public was about to see was appalling. The Scofield tragedy, at the time it occurred in the opening year of the 20th century, was the worst mine disaster in United States history. By the time the decade of the nineteen-aughts came to a close, Scofield was the fourth-worst mine accident, eclipsed in short order by the deaths of 362 at Monongah, West Virginia, December 7,1907; 239 at Van Meter (Jacobs Creek), Pennsylvania less than two weeks later on December 19, 1907; and 259 at Cherry, Illinois, November 13, 1909. The 1,060 deaths in these four accidents helped make the first decade of the twentieth century the deadliest in U.S. history for miners.

In response to the appalling loss of life in the decade that opened with the Scofield disaster, the beginning of the next decade brought the creation of the U.S. Bureau of Mines, establishment of a nation-wide system of mine rescue stations, the first workers compensation laws, and most of all, effective regulation of mine safety that has led to dramatic improvements in mine safety.

-------------------------------------------

And that, dear Kossacks, is where regulation comes from -- not from bored bureaucrats sitting in an office in Washington trying to think up ways to make life miserable and expensive for some innocent and unsuspecting businessman, but from real human suffering and tragedy brought about, all too often, by people who shirk what should be obvious responsibilities, who neglect basic diligence, who sacrifice safety for profit. They bring suffering on those who trust them and their products, and society adopts measures to make sure it never happens again. We have to force them, through regulation, to behave as they should have been behaving all along. That's how regulation came to be.

-------------------------------------

Previous installments of How Regulation came to be: