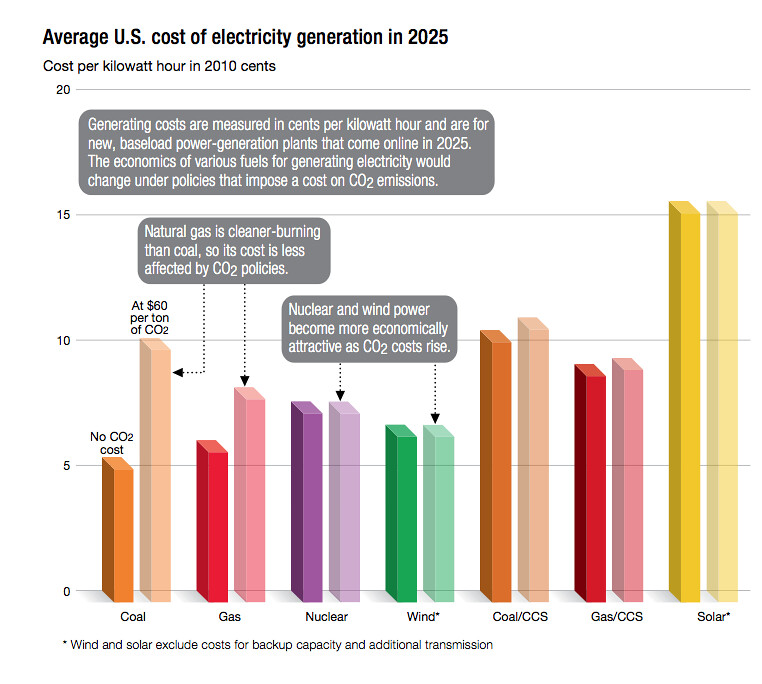

Sometimes, a graph says it all. This one is from ExxonMobil's yearly review of energy statistics and trends, called Energy Outlook: A view to 2030:

as usual, the full disclosure: I work in the wind business, helping projects get financing, and I write about wind - full list of articles here

If you look at the fine print, you see two provisos:

- to be cheaper, wind requires that carbon emissions be taxed to some extent (with no taxation, coal and gas-fired electricity still look cheaper). At heart, putting a price on carbon is a political decision which will be taken and accepted to the extent people accept that they have a responsibility towards future generations and show a willingness to bear (some of the) cost for highly diffuse externalities. Someone will pay for all that carbon in the atmosphere, we just don't know who or when exactly; putting a price on carbon is a collective way to acknowledge that cost and integrate it to current modes of power production. What is certain is that wind imposes no such externality on future generations and that, even if that cost is not taken into account, the cost of wind power is not that different from that of coal or gas-fired power.

- Exxon notes that the cost of wind excludes the cost for backup capacity and additional transmission. But this applies just as much to individual coal-fired or gas-fired plants: a big 2GW coal plant presumably needs the same capacity available on standby in case there is a production or transmission failure in that plant, yet you never hear the argument about backup costs made about coal-fired power, because the power system has long been designed to cope with such needs. But the reality is that this makes the system able to deal with wind intermittency just as well, for low and medium penetrations, at almost no additional cost. Wind power is intermittent but predictable, just like daily changes on the demand side; so current systems can manage just fine. The real issue is the potential future scenario where wind penetration is so high that you could conceivably have times with high demand, low wind, and not enough remaining capacity to cope with such demand. In such cases, you would indeed need to pay for spare generation capacity to cope with the lack of wind power generation. But beyond the fact that such scenarios are rather far off (you'd need wind at 30-40% penetration, rather than the 5-10% you have today), the price for such backup, even if borne exclusively by wind power assets, would be rather low (backing up each wind MW by a gas MW, which would represent a massive over-investment even compared to worst case needs, would only increase the price of wind kWh by 25% or so).

And of course, the cost of coal and gas ignores the massive indirect costs we bear today when producing and transporting gas and coal - the cost of military deployments in the Gulf (Qatar, the largest gas exporter in the Persian Gulf, is basically a large aircraft carrier for the US military) and elsewhere, the health costs from coal mining, and the unmeasured costs coming from depending on supposedly unstable suppliers (remember the "gas weapon" which we're putting in the hands of the Russians by buying their gas?)

So the conclusion can be that wind costs roughly the same as traditional power sources - with none of their drawbacks, whether troublesome exporters to deal with, dangerous mining practices for local communities or unhealthy, and durable, by-products. And it's ExxonMobil saying so.