As the Occupy Wall Street demonstrators House Minority Leader Eric Cantor called "mobs" took their protests to cities around the country, Republican frontrunners Mitt Romney and Herman Cain denounced the rallies as "class warfare." Meanwhile in Washington, President Obama signaled his support for a 5.6% tax surcharge on annual incomes over a million dollars in order to pay for his $447 billion American Jobs Act designed to help alleviate the struggles of the 99% now taking to the streets.

One would think that that the other 1% would be only too happy to help out. After all, even with the wildly popular surcharge beginning in 2013, the tax bite for America's millionaires would look little different than during the Clinton era (35 percent income tax rate now versus 39.6%; capital gains rate of 15% now versus 20 percent then) when they and almost everyone else enjoyed a booming economy. More importantly, with income inequality at its highest level in 80 years while the federal tax burden is at its lowest in 60, the top 1% has already triumphed in the class war Republicans continue to fight on their behalf.

Of course, a truism of American politics is that the side decrying class warfare is the one winning it. That's why a month after House Majority Leader Eric Cantor accused Barack Obama of wanting to "to incite class warfare," South Carolina Republican Senator Lindsey Graham called for still lower upper-class tax rates. Meanwhile, Paul Ryan, whose GOP budget would deliver another multi-trillion dollar tax cut windfall to the richest Americans, blasted President Obama:

"Class warfare may make for really good politics, but it makes for rotten economics."

As the numbers show, Ryan's description is only half right. As the Daily Beast reported, "a Washington Post/ABC poll released this week showed that 75 percent of respondents supported raising taxes on Americans with incomes over $1 million a year. In a CBS poll, 64 percent of respondents said they would support a tax on millionaires to lower the deficit, while only 30 percent would oppose it." And after decades of massive upward income redistribution, the Democrats' math is correct in concluding that modest tax increases on the wealthy must be part of any long-term debt reduction solution.

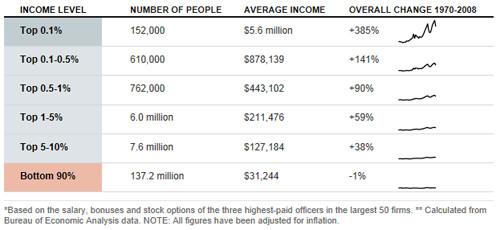

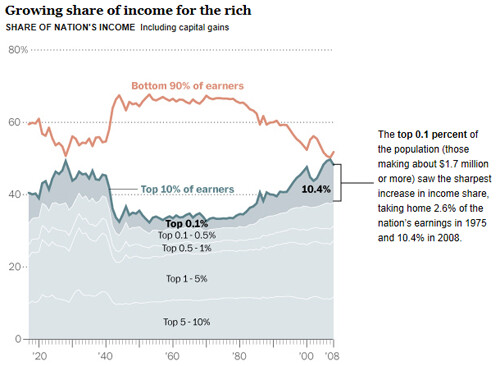

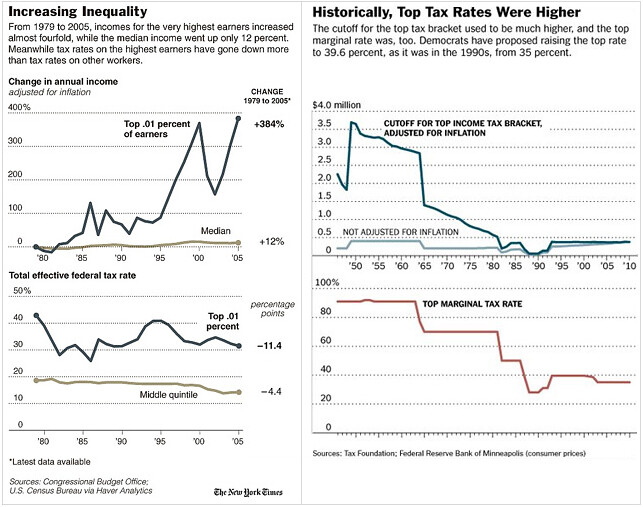

As the Washington Post demonstrated in its jaw-dropping series "Breaking Away," plummeting tax rates overall and on capital gains in particular have been widening the chasm between the rich and everyone else in America:

Nevertheless, Republicans would still rather wave the unbloodied shirt of class warfare than ask what America's rich and famous can do for their country.

That became abundantly clear during the debt ceiling crisis Republicans manufactured. Weeks before Cantor's August Washington Post op-ed accused President Obama accused President Obama of class warfare and a desire to "make it harder to create jobs," his GOP colleagues were already singing from the same hymnal. Senators Dan Coats (R-IN) and Kelly Ayotte (R-NH) quickly called a proposed $4 trillion debt reduction deal 17 percent of which came from new revenues "class warfare." Utah's Orrin Hatch wasn't content to lament "the usual class warfare the Democrats always wage." The poor, Hatch insisted, "need to share some of the responsibility." As for a Senate resolution asking the same of millionaires, Alabama Republican Jeff Sessions said that was "rather pathetic."

Of course, what is really pathetic is the declining tax burden on the small slice of Americans now taking an ever-larger piece of the economic pie.

Even after extorting in December a two-year extension to the upper-income Bush tax cuts and steep reductions in the estate tax impacting only 0.25% of families, Republicans refused to countenance a dime of new tax revenue as the debt ceiling debate began. First Eric Cantor and then John Boehner walked out of the debt compromise discussions with President Obama for the same reason. As Boehner put it in his national address in July, "I know those tax increases will destroy jobs."

Back in May, John Boehner explained to CBS News who Republicans would be trying to protect during the debt ceiling negotiations with President Obama:

"The top one percent of wage earners in the United States...pay forty percent of the income taxes...The people he's talking about taxing are the very people that we expect to reinvest in our economy."

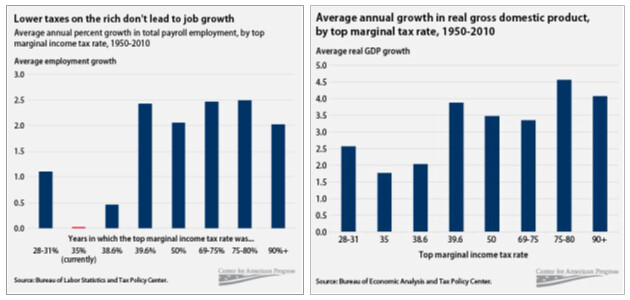

If so, those expectations were sadly unmet after the tax cuts of George W. Bush. After all, the last time the top tax rate was 39.6% during the Clinton administration, the United States enjoyed rising incomes, 23 million new jobs and budget surpluses. Under Bush? Not so much.

On January 9, 2009, the Republican-friendly Wall Street Journal summed it up with an article titled simply, "Bush on Jobs: the Worst Track Record on Record." (The Journal's interactive table quantifies his staggering failure relative to every post-World War II president.) The meager one million jobs created under President Bush didn't merely pale in comparison to the 23 million produced during Bill Clinton's tenure. In September 2009, the Congressional Joint Economic Committee charted Bush's job creation disaster, the worst since Hoover.

As David Leonhardt of the New York Times aptly concluded last year:

Those tax cuts passed in 2001 amid big promises about what they would do for the economy. What followed? The decade with the slowest average annual growth since World War II. Amazingly, that statement is true even if you forget about the Great Recession and simply look at 2001-7.

The data are clear: lower taxes for America's so called job-creators don't mean either faster economic growth or more jobs for Americans.

But while Boehner's job creators didn't create any jobs after the top rate was trimmed to 35% and capital gains and dividends taxes were slashed, they did enjoy an unprecedented windfall courtesy of the United States Treasury.

For Republicans, this predictable result of the Bush tax cuts was a feature, not a bug.

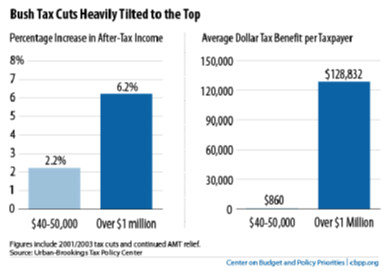

As the Center for American Progress noted in 2004, "for the majority of Americans, the tax cuts meant very little," adding, "By next year, for instance, 88% of all Americans will receive $100 or less from the Administration's latest tax cuts."

But that's just the beginning of the story. As the CAP also reported, the Bush tax cuts delivered a third of their total benefits to the wealthiest 1% of Americans. And to be sure, their payday was staggering. The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities showed that millionaires on average pocketed almost $129,000 from the Bush tax cuts of 2001 and 2003. As a result, millionaires saw their after-tax incomes rise by 6.2%, while the gain for those earning between $40,000 and $50,000 was paltry 2.2%.

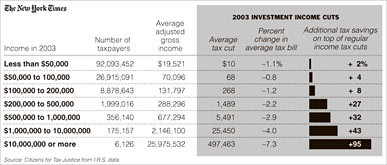

And as the New York Times uncovered in 2006, the 2003 Bush dividend and capital gains tax cuts offered almost nothing to taxpayers earning below $100,000 a year. Instead, those windfalls reduced taxes "on incomes of more than $10 million by an average of about $500,000." As the Times explained in a shocking chart: "The top 2 percent of taxpayers, those making more than $200,000, received more than 70% of the increased tax savings from those cuts in investment income."

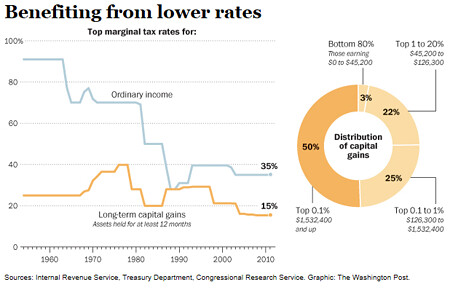

And as the Washington Post explained last week, for the very richest Americans the successive capital gains tax cuts from Presidents Clinton (to 20 percent) and Bush (to 15 percent) have been "better than any Christmas gift":

While it's true that many middle-class Americans own stocks or bonds, they tend to stash them in tax-sheltered retirement accounts, where the capital gains rate does not apply. By contrast, the richest Americans reap huge benefits. Over the past 20 years, more than 80 percent of the capital gains income realized in the United States has gone to 5 percent of the people; about half of all the capital gains have gone to the wealthiest 0.1 percent.

This convenient chart tells the tale:

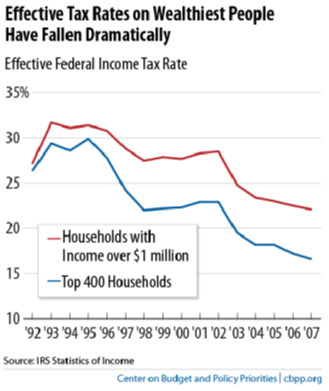

It's no wonder that between 2001 and 2007- a period during which poverty was rising and average household income had fallen - the 400 richest taxpayers saw their incomes double to an average of $345 million even as their effective tax rate was virtually halved. As the Washington Post noted, "The 400 richest taxpayers in 2008 counted 60 percent of their income in the form of capital gains and 8 percent from salary and wages. The rest of the country reported 5 percent in capital gains and 72 percent in salary."

(It's worth noting that the changing landscape of loopholes, deductions and credits, especially after the 1986 tax reform signed by President Reagan, makes apples-to-apples comparisons of marginal tax rates over time very difficult. For more background, see the CBO data on effective tax rates by income quintile.)

As ThinkProgress demonstrated (see charts above), historically lower tax rates for the richest Americans did not produce either more job creation or faster economic growth. (In fact, the Bush years produced what David Leonhardt of the New York Times rightly labeled as "The decade with the slowest average annual growth since World War II.") But what the conservative cornucopia for the gilded-class does reliably produce is unprecedented income inequality.

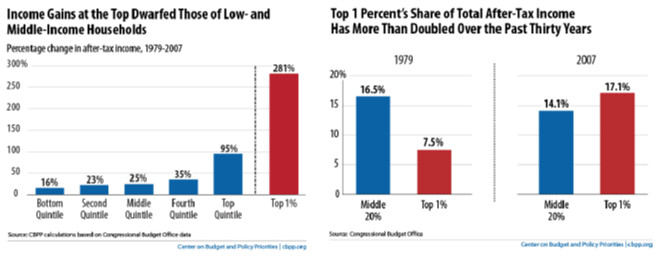

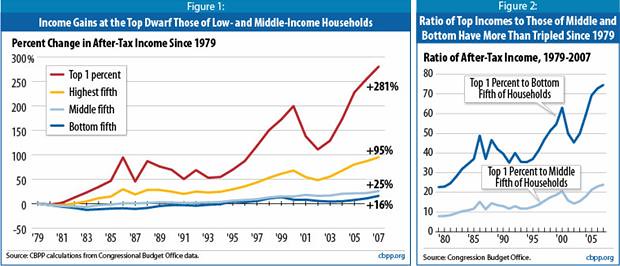

A report from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP) found a financial Grand Canyon separating the very rich from everyone else. Over the three decades ending in 2007, the top 1 percent's share of the nation's total after-tax household income more than doubled, from 7.5 percent to 17.1 percent. During that time, the share of the middle 60% of Americans dropped from 51.1 percent to 43.5 percent; the bottom four-fifths declined from 58 percent to 48 percent. As for the poor, they fell further and further behind, with the lowest quintile's income share sliding to just 4.9%. Expressed in dollar terms, the income gap is staggering:

Between 1979 and 2007, average after-tax incomes for the top 1 percent rose by 281 percent after adjusting for inflation -- an increase in income of $973,100 per household -- compared to increases of 25 percent ($11,200 per household) for the middle fifth of households and 16 percent ($2,400 per household) for the bottom fifth.

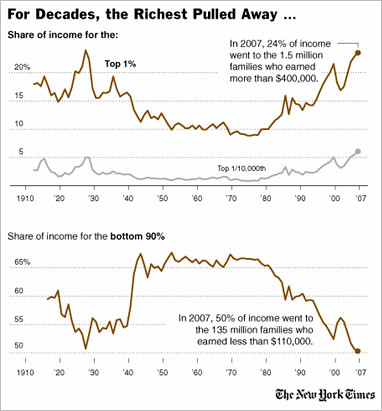

As the New York Times revealed in August 2009, by 2007 the top 1% - the 1.5 million families earning more than $400,000 - reaped 24% of the nation's income. The bottom 90% - the 136 million families below $110,000 - accounted for just 50%.

If you had any lingering doubts about Warren Buffett's admission that "it's my class, the rich class, that's making war, and we're winning," this pair of charts from the New York Times should put them to rest. As the upper-income tax burden fell, income inequality in the U.S. exploded.

The pathetic irony is that 98% of Republicans in Congress voted for the Ryan budget proposal which would make both income inequality and the national debt much worse. Analyses by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities showed that the Bush tax cuts accounted for half of the deficits during his tenure, and if made permanent, over the next decade would cost the U.S. Treasury more than Iraq, Afghanistan, the recession, TARP and the stimulus - combined. The Ryan budget adds $6 trillion in new debt over the next 10 years (necessitating, of course, that Republicans raise the debt ceiling repeatedly), $4 trillion of which is dedicated to new tax cuts.

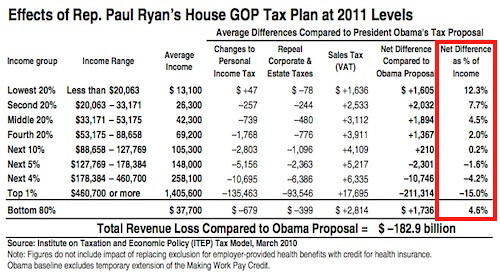

And as Matthew Yglesias explained, earlier analyses of similar proposals in Ryan's Roadmap reveal that working Americans would have to pick up the tab left unpaid by upper-income households as the top rate is dropped from 35% to 25%:

This is an important element of Ryan's original "roadmap" plan that's never gotten the attention it deserves. But according to a Center for Tax Justice analysis (PDF), even though Ryan features large aggregate tax cuts, ninety percent of Americans would actually pay higher taxes under his plan.

In other words, it wasn't just cuts in middle class benefits in order to cut taxes on the rich. It was cuts in middle class benefits and middle class tax hikes in order to cut taxes on the rich. It'll be interesting to see if the House Republicans formally introduce such a plan and if so how many people will vote for it.

We now know the answer: 235 House Republicans and 40 GOP Senators.

On tax day in 2009, former Bush press flunky Ari Fleischer fretted about proposals to raise upper-income tax rates. (The top 10% of taxpayers, Fleischer argued, are "supporting virtually everyone and everything" and "their burden keeps getting heavier." As he also put it, "It's also what's called redistribution of income, and it is getting out of hand.") But it was Michele Bachmann who in February 2009 coined the slogan for the Republican class warriors:

"We're running out of rich people in this country."

She need not have worried.

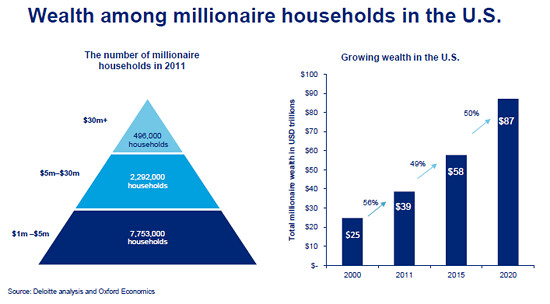

As the Los Angeles Times explained in "Millionaires Make a Comeback", by 2010 the wealthy had more than made up their losses from the Bush Recession. (The middle class has not been so lucky.) Executive pay rose by 23% last year. Since 2009, corporate profits "captured 88% of the growth in real national income while aggregate wages and salaries accounted for only slightly more than 1% of the growth in real national income." By last summer, the Wall Street Journal proudly proclaimed, "U.S. Economy Is Increasingly Tied to the Rich." As a recent Deloitte presentation for wealth managers forecast:

Our analysis indicates that aggregate wealth of millionaire households in the U.S. in 2020 will likely reach $87 trillion, from $39 trillion in 2011.

That good news was no consolation for Harvey Golub, who now carries the Republicans' water at the American Enterprise Institute. Despite last year's reductions in the estate tax, Golub whined that "it is unfair" that "gifts to charities are deductible but gifts to grandchildren are not." Golub concluded:

"Before you 'ask' for more tax money from me and others, raise the $2.2 trillion you already collect each year more fairly and spend it more wisely. Then you'll need less of my money."

To put it bluntly, that's rich.

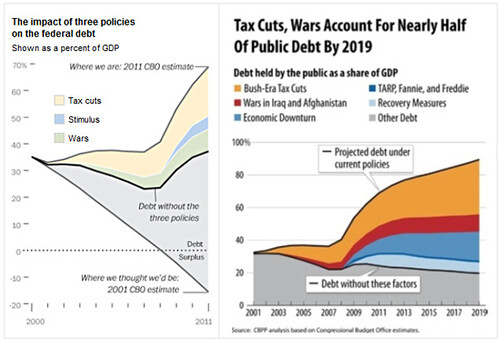

Earlier this year, the Washington Post summed up data from the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office (CBO) to explain the origins of the $14.3 trillion U.S. debt. As the numbers show, history did not, as Republicans pretend, start on January 20, 2009:

The biggest culprit, by far, has been an erosion of tax revenue triggered largely by two recessions and multiple rounds of tax cuts. Together, the economy and the tax bills enacted under former president George W. Bush, and to a lesser extent by President Obama, wiped out $6.3 trillion in anticipated revenue. That's nearly half of the $12.7 trillion swing from projected surpluses to real debt.

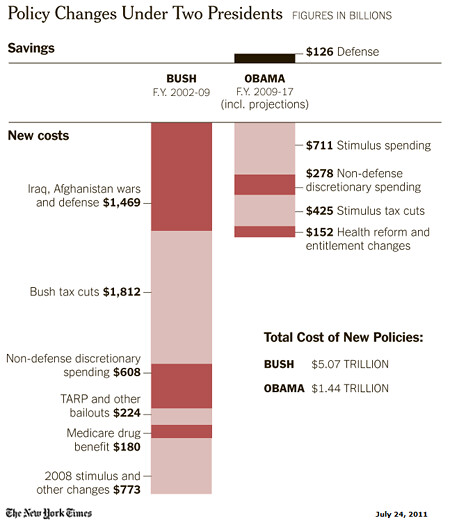

Now, the New York Times has examined the tsunami of debt that began sweeping over the United States when George W. Bush ambled into the White House in 2001. As this chart shows, Bush's policies along with the recession he presided over not only washed away the projected surpluses he inherited from Bill Clinton, but were also largely responsible for draining the Treasury for his successor Barack Obama:

With President Obama and Republican leaders calling for cutting the budget by trillions over the next 10 years, it is worth asking how we got here -- from healthy surpluses at the end of the Clinton era, and the promise of future surpluses, to nine straight years of deficits, including the $1.3 trillion shortfall in 2010. The answer is largely the Bush-era tax cuts, war spending in Iraq and Afghanistan, and recessions.

Despite what antigovernment conservatives say, non-defense discretionary spending on areas like foreign aid, education and food safety was not a driving factor in creating the deficits. In fact, such spending, accounting for only 15 percent of the budget, has been basically flat as a share of the economy for decades. Cutting it simply will not fill the deficit hole.

As the Times noted, "the Bush tax cuts have had a huge damaging effect. If all of them expired as scheduled at the end of 2012, future deficits would be cut by about half, to sustainable levels." But for Republicans, this was a feature of the Bush tax cuts and not a bug. After all, in January 2001 Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan blessed the Bush tax cuts because he was worried that the projected surpluses were too large. For the same reason, a young Congressman Paul Ryan fretted that the windfall for the wealthy was "too small" and "not big enough to fit all the policy we want."

Leave aside for the moment that Ronald Reagan tripled the national debt and increased the debt ceiling 17 times. Forget also George W. Bush nearly doubled the debt or that the Bush tax cuts were the biggest driver of debt over the past decade, and if made permanent, would be continue to be so over the next. Pay no attention to the federal tax burden now at its lowest level in 60 years or income inequality at its highest level in 80 years after a decade of plummeting rates for America's supposed job creators who don't create jobs. Ignore for now that Republican majorities voted seven times to raise the debt ceiling under President Bush and the current GOP leadership team voted a combined 19 times to bump the debt limit $4 trillion during his tenure. Look away from the two unfunded wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, the budget-busting Bush tax cuts of 2001 and 2003 and the Medicare prescription drug program because, after all, John Boehner, Eric Cantor and Mitch McConnell voted for all of it.

Utah Senator Orrin Hatch was telling the truth when he described Republican fiscal management during the Bush years by acknowledging, "It was standard practice not to pay for things." But House Minority Leader Eric Cantor was lying when he protested in July:

"What I don't think that the White House understands is how difficult it is for fiscal conservatives to say they're going to vote for a debt ceiling increase."

Or, as Dick Cheney, who complained that after the S&P downgrade of U.S. credit "I literally felt embarrassed for my country," famously put it, "Reagan proved deficits don't matter."

Not, the record shows, if a Republican is in the White House. Or if the richest people and most profitable corporations in America are asked to pay one more cent of it.

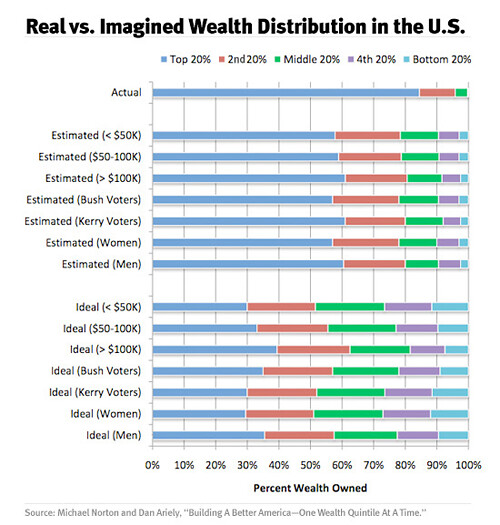

But even more than the facts revealing America's yawning wealthy gap, the totality of the victory of the top 1% is reflected in Americans' perceptions of it. As Timothy Noah explained in Slate a year ago, the actual distribution of wealth in the United States is far more skewed than Americans believe it is or ideally should be:

That misperception about a class war already fought and won by the rich, Noah suggested, explained Americans' quiescence. As he concluded just weeks before the Republicans' 2010 midterm rout:

In 1915, when the richest 1 percent accounted for about 18 percent of the nation's income, the prospect of class warfare was imminent. Today, the richest 1 percent account for 24 percent of the nation's income, yet the prospect of class warfare is utterly remote. Indeed, the political question foremost in Washington's mind is how thoroughly the political party more closely associated with the working class (that would be the Democrats) will get clobbered in the next election. Why aren't the bottom 99 percent marching in the streets?

A year after Noah asked the question, Occupy Wall Street may finally be providing the answer.

* Crossposted at Perrspectives *