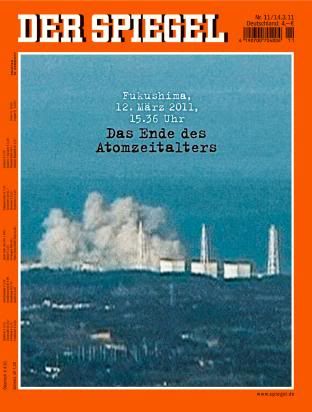

Apparently the Spiegel has decide to declare the end of the nuclear age, following the serious incidents at the Japanese plants. I must say I don't buy it yet, even as it's obvious that the politics of nuclear just got a bit more complicated for supporters even if the facts don't really support that.

Apparently the Spiegel has decide to declare the end of the nuclear age, following the serious incidents at the Japanese plants. I must say I don't buy it yet, even as it's obvious that the politics of nuclear just got a bit more complicated for supporters even if the facts don't really support that.

On my side, here a few non-obvious facts about the incidents of the past few days:

- earthquake kills people, nuke power plants don't kill people. Despite being hit by a very large natural event, damage seems limited to the nuclear plants themselves, with no real material consequences outside the plants. Even with an accumulation of adverse events (earthquake + tsunami), the overall safety design seems to have, ultimately, functioned;

- earthquakes is what costs money. Overall, the damage to the nuclear plants seems less than to much of the infrastructure which was hit by the earthquake+tsunami, and it's not obvious that the damage to the nuclear plants will cost more than a small fraction of the overall damage; an immediate question is thus whether the damage to these plants should be included in the cost of electricity or in the cost of earthquake insurance;

- centralised power plants have a cost. Nuclear power plants are large single points of failure - an immediate cost for consumers will be felt as the large nuclear capacity now offline will need to be replaced by more expensive gas-fired power (fuelled, in Japans's case, by LNG imports), if available, and tensions in the power network may lead to rolling blackouts or other form of unreliability - or use of even more expensive oil-fuelled backups; This means that the nuclear industry needs to include such catastrophic events in the pricing of its energy - especially in an earthquake-prone place like Japan, via the incorporation of (i) a lowish, but not far from nil, probability of full loss of large chunks of generating capacity and (ii) the ongoing cost of the availability of a larger permanent reserve capacity to cope with temporary or permanent losses of capacity at large power plants;

- energy policy is the government's job. All of this underlines that the overall design of the power system hinges on the rules established by public authorities - from the mostly technical stuff on how much backup the system should have, to the allocation of the cost of insurance for large catastrophes, to the safety margins to take into account (ie what threshold of frequency for catastrophic events that you have to deal with, and how big a disruption should be factored in) and to the cost of funding the plants themselves as well as whatever additional safety features you impose on them.

I do expect that there will be political consequences to these incidents, just because, as the Spiegel points out, unusual things happened basically live on TV and these can be spun in so many ways by interested parties. I suspect that the winners will be the coal industry, a bit (in Europe, in the form of a slower phase-out; elsewhere, in the form of fewer restrictions) and, to a greater extent, the gas industry - even if there was probably quite a bit of damage to the gas infrastructure from the earthquake, and even if the long term worries about availability and security of supply are not closer to being answered - it's just the easy, default solution for lazy governments facing highly motivated lobbying and pervasive ideological support (if it's the market's choice, it has to be better). I don't really expect the wind industry to benefit much, given the gap in perception between the evil subsidies given to renewable energies and the "price to pay for our civilisation" nature of the cost of dealing with burning refineries or large-scale inteeruptions of production from centralised plants.

I do expect that there will be political consequences to these incidents, just because, as the Spiegel points out, unusual things happened basically live on TV and these can be spun in so many ways by interested parties. I suspect that the winners will be the coal industry, a bit (in Europe, in the form of a slower phase-out; elsewhere, in the form of fewer restrictions) and, to a greater extent, the gas industry - even if there was probably quite a bit of damage to the gas infrastructure from the earthquake, and even if the long term worries about availability and security of supply are not closer to being answered - it's just the easy, default solution for lazy governments facing highly motivated lobbying and pervasive ideological support (if it's the market's choice, it has to be better). I don't really expect the wind industry to benefit much, given the gap in perception between the evil subsidies given to renewable energies and the "price to pay for our civilisation" nature of the cost of dealing with burning refineries or large-scale inteeruptions of production from centralised plants.