I was invited to speak in Brussels earlier last week about the financing of energy infrastructure. It was a breakfast organised by the European Energy Reviewand Interel.

I had the opportunity to make a presentation outlining some of the points I've made here on many occasions (the importance of the cost of capital, the difference between profitable and cheap, and the fact that "market-based" policies are not technology neutral) and as these themes are not specific to Europe but also largely apply to the USA I'm copying the slides below the fold with some accompanying comments.

Added to my Wind Power series with the usual disclosure: I advise wind developers on their financing needs

(yes, my firm's slides have a google-esque emptiness about them)

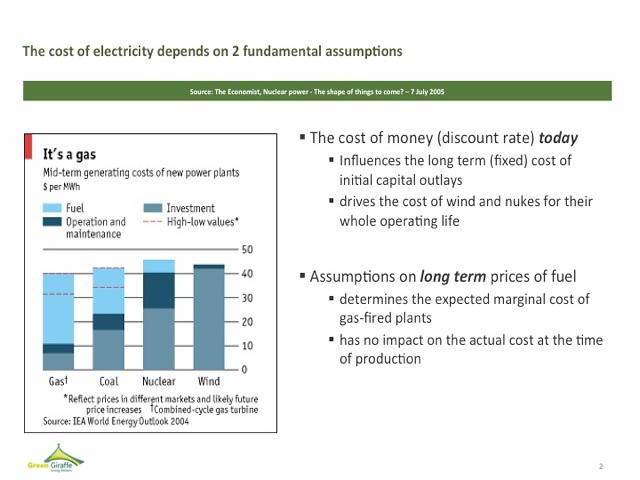

I started right off with the differences in cost structures between fuel based power sources (low capital costs, large fuel cost) and wind (or nuclear (high capital costs, low running costs) and thus the importance of the assumptions one makes (or has to make) about discount rates and the price of gas.

I added a point that I don't think I've made here before, ie that the assumption about the cost of capital decides what the cost of wind power will be for the next twenty years, whereas the assumption one makes about the price of gas has no actual impact on the actual price of electricity in the future, which will be driven by the real price of gas then. That means that investing in a high capital cost piece of equipment is a much bigger bet on future economic conditions than investing in an initiallly less expensive piece of kit.

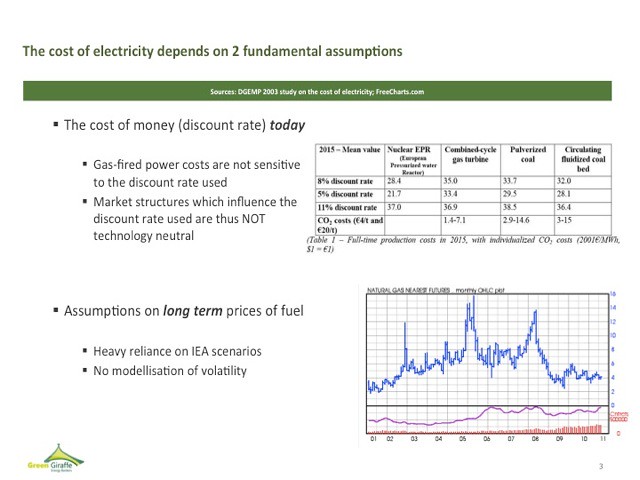

That slides provides more detail on the factors identified above, to note that (i) the discount rate has a much bigger impact on the cost of capital-intensive technologies than on the cost of gas-fired power plants and (ii) gas price assumptions are typically based on IEA scenarios, which generally show gentle upwards slopes with no volatility, whereas the reality can be quite different.

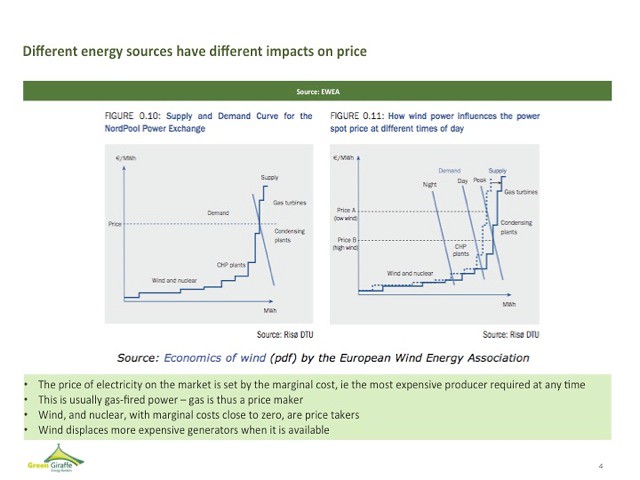

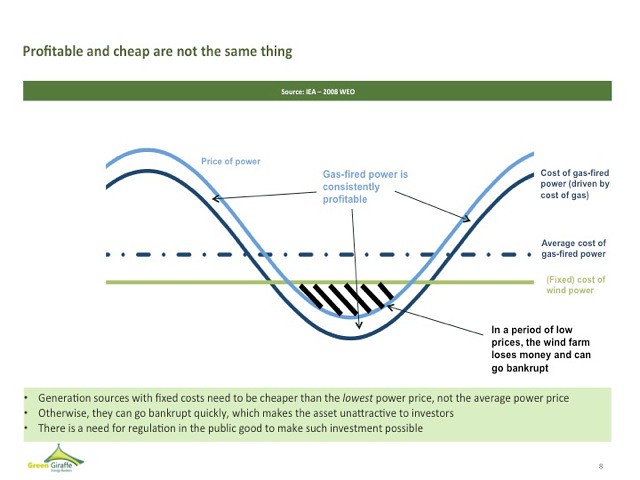

My next step is to discuss the dispatch curve, remind everybody that market prices of electricity are driven by marginal costs which are low for nukes and wind, and high for gas-fired plants (and linked to the price of gas). I make two further points which set gas-fired plants from wind farms:

- gas-fired power plants are largely price makers: it is their cost which drives market prices, and thus gas-fired power plants are pretty sure to always receive revenues close to what they need to cover their costs;

- wind farms are price takers, but their effect on the system is to bring prices down, as they displace more expensive plants when wind blows (that's what is called the "merit-order effect", which I've discussed extensively in the past in my wind series);

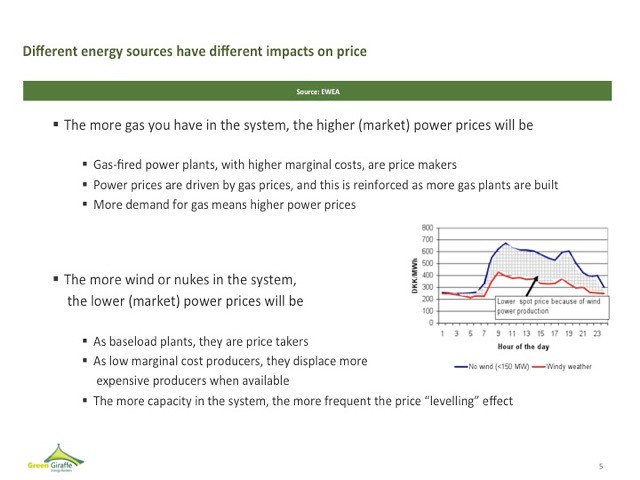

I take this to the logical conclusion:

- the more gas you have in the system, the higher the price of electricity on the market will be;

- the more wind you have in the system, the lower the price of electricity on the market will be.

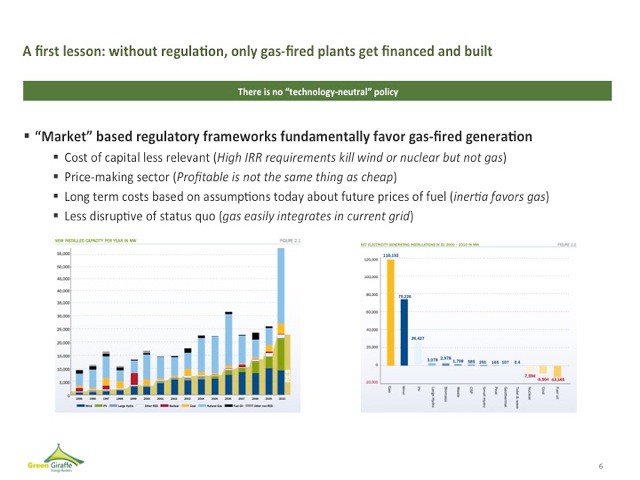

The next graphs show that reality does follow theory: over the past 15 years, as markets were deregulated, European power companies have built gas-fired power plants and nothing else - to the exception of renewables, thanks to very specific carve-outs in market regulations. De-regulated markets only get gas-fired power plants built, but that easily understood when you follow my previous arguments; gas-fired power plants are much less risky to invest in and, in a context where investment has to come from the private sector and money is more expensive than if provided by publicly-funded entities, capital-intensive goods tend to be avoided.

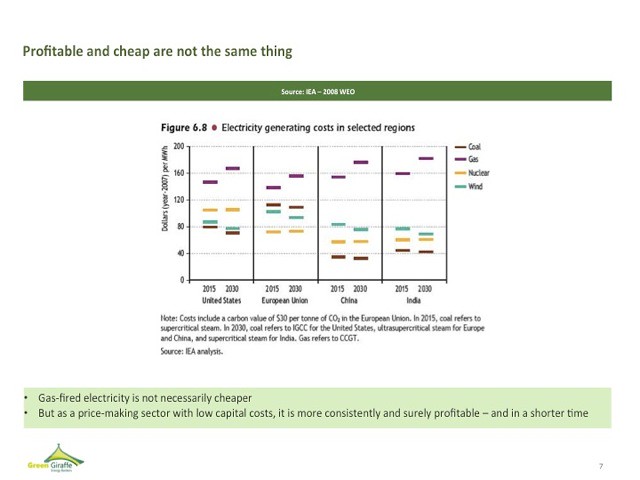

I used IEA data to underline that this does not even mean that gas-fired power plants are expected to be cheaper, in the long run, and use the following slide to show how profitable and cheap are not the same thing:

Wind power needs to be cheaper than the lowest cost of electricity over the next 15 years in order for a windfarm not to go bankrupt at some point in time in the period: in effect, wind power needs to be cheaper than what gas-fired power would cost if using the lowest price of gas possible for the 15-year period. This is a typical case of a public good (cheaper average cost of production) is inaccessible because of a private constraint (the investment does not make sense for you if you can go bankrupt at some point in the process, even if you'd make good money on average over time)

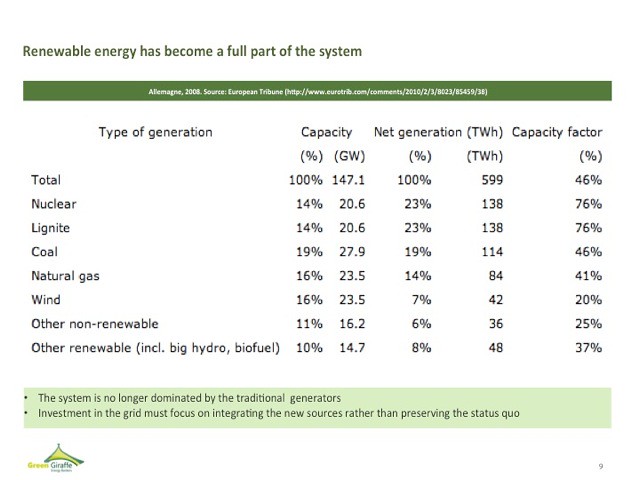

Finally, I used a table provided by DoDo (here) about Germany, and which I note is already obsolete, as 12 GW of solar and 3 GW of wind have been installed since then, to make the point that renewables are no longer a marginal part of the system: they already represent almost half of the installed capacity and one sixth of total general generation in 2010, numbers which will continue to grow each year. So the grid cannot be seen as something to the service of traditional producers which somehow needs to incorporate renewables in - it is a system which is equally to the service of renewables (and so far it has been up to the task, despite what the naysayers have been saying for years), and needs to be adapted taking into account that reality.

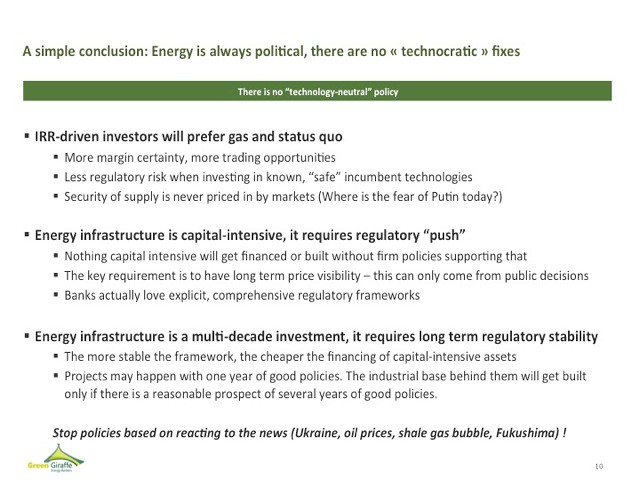

The last slide, which incorporates my conclusions, is self-explicit: there are no "neutral" policy choices, and energy will always be political - and it's time what the implicit political choices of current policies be acknowledged. I ended my presentation by my usual quip: it's time that European energy policies be something else than a jobs programme for City bankers and assorted parasites.

The other two speakers were the Spanish rapporteur of the European Parliament report on energy investment, and a senior representative of the European Commission. Both emphasised the need for stable regulatory frameworks and the need for agreements on cross-border investments, which is fine as far as it goes, and largely uncontroversial. The audience (to a large extent, the "public affairs" representatives of large companies or organisations of the sector (ie lobbyists) where largely in agreement with me and most of the questions focused on my presentation. One person underlined the fundamental differences between the perspectives of bankers and politicians, and said that politicians were especially unreliable partners and should listen to bankers more; I responded that while I agreed on the need for regulatory stability, I thought that the problem was that politicians listened to bankers too much and that they needed to take decisions in line with their goals, and stick to these without tinkering with things all the time. Bankers would grumble but would adapt to any consistent set of rules.