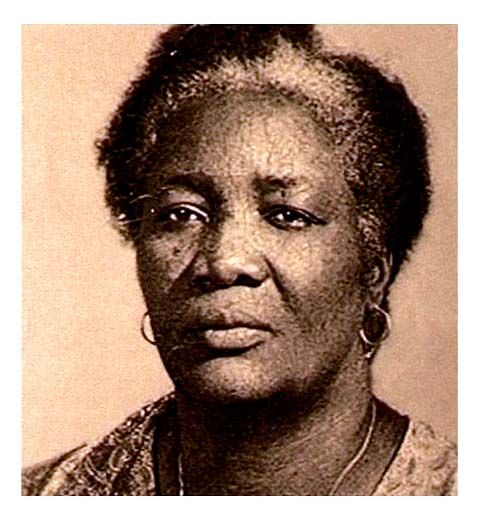

"I am Reyita, a regular, ordinary person. A natural person, respectful, helpful, decent, affectionate, and very independent. For my mother, it was an embarrassment, that I—of her four daughters—was the only black one."

On the Life and Times of "Reyita"

Commentary by Deoliver47

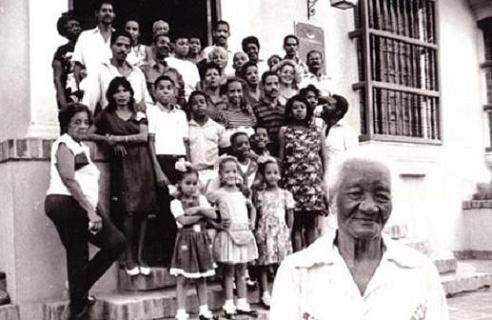

You will not know this black woman's face. She died at the age of 95 in Cuba in 1997. Though she speaks of herself as "ordinary" it is important that we hear the voices and herstories of more women who lived through extraordinary times in our shared history.

The first chapter of her story continues with her words:

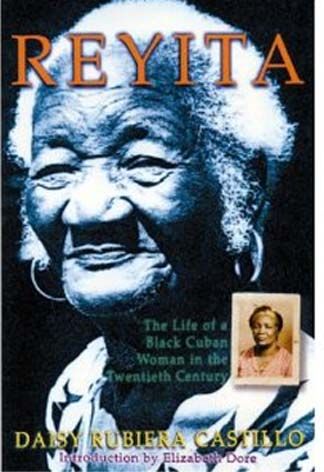

I always felt the difference between us, because she didn’t have as much affection for me as she did for my sisters. . . . I was the victim of terrible discrimination from my mother. And if you add that to the situation in Cuba, you can understand why I never wanted a black husband. I had good reason, you know. I didn’t want to have children as black as me, so that no one would look down on them, no one would harass and humiliate them. Oh, God only knows! I didn’t want my children to suffer what I’d had to suffer.”—from Reyita: The Life of a Black Cuban Woman in the Twentieth Century

What is the face of Cuba when you close your eyes and think of it? For my students it is still the face of Fidel Castro. For many people here in the US it may be the faces of "white" Republican Cuban emigres. For me, Reyita and her story is the Cuba I know.

Thanks to her daughter Daisy, it is a story we can all now share and learn from.

Daisy Rubiera Castillo, one of Reyita's daughters, is a founder of the Fernando Ortiz African Cultural Centre in Santiago de Cuba. Her book was published, first in Spanish, the year her mother died.

After the publication of the book a documentary film was made by Spanish filmmakers Oliva Acosta and Elena Ortega of Reyita's life and times and the process of the development of the book. It is not currently available here in the US but here is a trailer with English subtitles

The film aired at the Hollywood Black Film Festival in 2007

Reyita´s story would have gone unnoticed even by her own family, had her youngest daughter, Daisy, not decided to write about it. her mother Reyita, was the granddaughter of an Angolan slave brought to work on the sugar cane fields.Reyita saw her marriage as a source of stability, but soon enough she realized that her husband had become an obstacle to her dreams and those of her children. Thus, behind her husband's back, she helped other women -many of them prostitutes- to take care of their children. In the 1940s, she became a militant, while at the same time fighting everyday battles such as buying her children's clothing or getting a new radio to listen to her favorite soap opera. Thus, throughout her life Reyita got involved in many small but important struggles to change not just her home, but the world.

Anthropologist Helen Safa speaks of the importance of this book and the historical context of her story:

Against All Odds: Life as a Poor, Black Woman in Twentieth Century Cubaes, a 94 year old black Cuban woman recounts her life, including memories of her grandmother in slavery and her mother in the independence movement, and her observations of the 1912 massacre of the PIC (Partido Independiente de Color), plantation life, Fulgencio Batista (notorious dictator of Cuba in the l950s), the formation of the Popular Socialist Party (the Communist party of the time) and the socialist revolution in l959. But the most important aspect of this gem of a book is not a local rendition of national political events, but Reyita's own struggle to overcome all the obstacles in her life, which were overwhelming for a poor, black woman born in l902.

Race figures prominently in her life, but in a contradictory way. Reyita is proud of her blackness, and recounts her grandmother's recollections of life in Africa and the terrible trials of slavery. She maintains her African connections through her Spiritualism mixed with a folk Catholicism that makes primary the Virgen de la Caridad del Cobre, a national icon whom Reyita claims for her own salvation. Her racial awareness is also marked by her participation in the short-lived Marcus Garvey movement and her knowledge of the Partido Independiente de Color, formed after the U.S. occupation to protest the exclusion of blacks from Cuban politics and their racial subordination.

Let me digress a bit here to expand on this history. Many free and enslaved blacks in Cuba fought against Spain in the struggle for Independence and freedom from slavery – starting around 1868.

The forces for independence called themselves the Mambi Army.

The Mambi Army was the National Army of Liberation that defeated the Spanish through two wars: 1868 to 1878 and again, 1895 to 1898. Mambi is a Congo word. Recent estimates of the participation of Cubans of African descent in the Mambi run as high as 92%. Antonio Maceo, "the Bronze Titan," led the Mambi Army. His second in command was Quintín Bandera. In typical Congo fashion, their ritual roles were reversed: Bandera was the Tata Nkisi of the Mambi Army Nganga, the prenda or "magic cauldron" of the Mambises. And Antonio Maceo was the Mayordomo or Bakonfula of the prenda, which today is still a working prenda in Regla.

Invited by a Cuban plantocracy that was worried about the ascendancy of blacks, the Americans with Teddy Roosevelt intervened in 1898, routing a Spanish force that had already been defeated by the Mambi Army. And ironically enough, we now know that the 10th Cavalry, the Buffalo Soldiers, played a vital role in Teddy Roosevelt's adventure, providing the critical push that took San Juan Hill.

http://afrocubaweb.com/...

Slavery was abolished in Cuba in 1898.

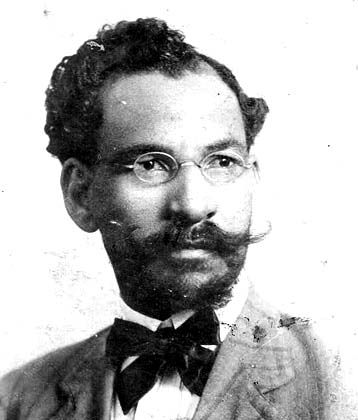

The Independent Colored Party(Partido Independiente de Color – PIC) was created in 1908 by Mambi vets. Among the leaders were Evaristo Estenoz and Pedro Ivanet.

Pedro Ivonet

Evaristo Estenoz

Not long after, in 1912 there was a massacre of Afro-Cubans.

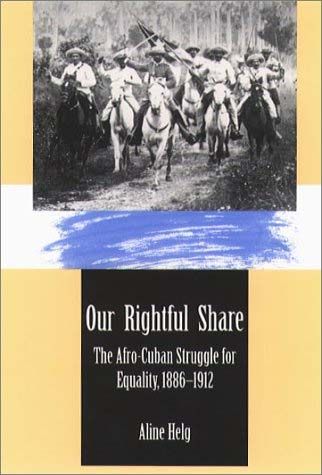

J.A. Sierra writes, citing Aline Helg author of Our Rightful Share: The Afro-Cuban Struggle for Equality, 1886-1912, that the 1912 Massacre was dubbed a "race war"

"The 'race war' of 1912 was, in reality, an outburst of white racism against Afro-Cubans." - Aline Helg in "Our Rightful Share, The Afro-Cuban Struggle for Equality, 1886-1912" At the end of the 2nd War for Independence, the prospect of peace and self-determination filled Afro-Cubans with a hope they had never been able to experience. They felt they had earned the rewards of a free society, and the very idea of self-government implied a free, integrated society with equal access to schools and business opportunities. This is what Martí and Maceo had promised. This is what 86,000 Afro-Cubans had died for in the War of Independence (1895-98). "Peace changed everything," wrote Louis A. Pérez, Jr. in The Hispanic American Historical Review. "Gains made during the war were annulled. The expatriate juntas disbanded. The provisional government dissolved, and the Liberation Army demobilized. Suddenly, all the institutional expressions of Cuba Libre in which Afro-Cubans had registered important gains disappeared, and with them the political positions, military ranks, and public offices held by thousands of blacks."

The Partido Independiente de Color, established in 1908 by Evaristo Estenoz and others, sought to correct the problems of the new republic, but found itself unable to push its agenda forward. The Morúa Law of 1909 banned political parties based on race or class, and even the government of liberal José Miguel Gómez had limited sympathy for their issues. One of these issues was the Morúa Law, which would not allow independents to run a candidate for president. Another issue was the ban limiting immigration by Haitians and Jamaicans. In 1910, leaders of the Partido Independiente de Color had been arrested and charged with conspiracy against the Cuban government. After a trial they were all found not guilty.

In order to protest the failure of the new republic to adhere to Marti's vision, and to call an end to the Morúa Law, the Partido Independiente de Color planned a demonstration for May 20 1912. Demonstrators chanted "Down with the Morúa Law! Long Live Gomez!" and there was no violence. The demonstration was quickly misrepresented as racist against whites, causing a great deal of panic and reviving old fears. "At the first sign of an Independiente show of force," wrote Helg, "the Cuban political elite labeled the movement as a race war that the Partido Independiente de Color had allegedly launched against the island's whites. Mainstream newspapers were particularly eager to propagate this view of the armed protest." Newspapers reported the demonstration as a race war, arousing great fear among white Cubans. Publications such as El Día, La Discusión, La Prensa, El Triunfo, El Mundo, and others, ran with the "race" idea, stirring the traditional race fears of white Cuban society. Reports of Afro-Cuban rapes of white women, including a teacher (none of which were true) and exaggerated accounts of the demonstrations, inspired white militias to form all over the island, and the "race war" became the main topic of conversation... Exaggerated and downright inaccurate reports of black attacks on whites, murders and rapes, were everywhere. Later reports would prove them all completely wrong.

This history is part of Reyita's story, yet until recently was not even dealt with very openly in Cuba. Is there any wonder that Reyita came to desire lighter skin for her children?

We know the history of lynching in the US. I doubt that many of us associate it with Cuba. Sierra continues:

All over the island, Afro-Cubans were arrested, harassed, and killed, simply out of "suspicion." Suddenly, in May and June of 1912, it was very dangerous to be of dark skin in Cuba. Men and women were attacked by militias as they were walking home from work, or visiting with friends. There was a great deal of suspicion that all Afro-Cubans were secretly involved in the "race war." On May 23, police near Cienfuegos shot to death 8 "peaceful negroes." Black skin was enough reason to suspect a person, and suspicion seemed to be enough reason for execution...The massacre continued into June. In Boquerón, near Guantánamo Bay, a captain and five volunteers beheaded a policeman and stabbed to death five others who had been arrested on an unsubstantiated charge of conspiring with Jamaicans to aid the rebels. On June 10 the U.S. consul filed a report stating that "many innocent and defenseless negroes in the country are being butchered." Bodies of suspected "rebels" were left hanging outside the towns for "moral reasons," and severed heads were placed on the side of the railroad tracks so train passengers could see them.

Whatever myth existed about racial equality in Cuba was shattered in May and June 1912. Not only was there no significant cry of outrage about the massacre from white Cubans, but the majority of newspaper accounts and editorials expressed a kind of racism not seen in Cuba since immediately after the abolition of slavery in 1886.

Editorials pointed out that in Cuba "one of two (opposed races) forcibly has to succumb or to submit: to pretend that both live together united by bonds of brotherly sentiment is to aspire to the impossible." Others recommended that Cuba be "ruled by a small white elite, through a system of plural vote that overrepresented the upper class, and that blacks' access to politics and public jobs be limited because of their 'lesser preparation.' And yet others suggested looking to the U.S. for a blueprint on "race relations."

- -

"This massacre achieved what Morúa's amendment and the trial against the party in 1910 had been unable to do," wrote Helg, "it put a definitive end to the Partido Independiente de Color and made clear to all Afro-Cubans that any further attempt to challenge the social order would be crushed with bloodshed."

It is into this world of racism and total suppression that Reyita was born. And yet she discusses attending organizing meetings of the Garvey Movement, and pride in her father and mother's participation in rebellion.

Safa discusses further the intersections of race, skin-color, social class and gender in Reyita's life:

As the blackest child of a mixed race woman, born of an African mother and a slave master, Reyita is discriminated against by her own mother and other members of her large, extended family. She is also discriminated against in education and employment, and never finds formal employment, but is always active earning money through teaching, washing clothes, selling home-cooked food, and other means to sustain her 11 children. The final betrayal is by her white husband, who deceives her into thinking they are formally married through an elaborate wedding ceremony. She is shocked to discover many years later, in her fifties, that the marriage was never formally registered. She marries a white man consciously, to improve her race (adelantar la raza), so that her children may have less difficulty in life than she has faced as a poor black woman. In the United States, marriage to a white spouse may be seen as racial betrayal, but not in Cuba, where intermarriage was a prime mover in the integration of blacks into Cuban society. As Reyita says, "I didn't want a black husband, not out of contempt for my race, but because black men had almost no possibilities of getting ahead and the certainty of facing lots of discrimination".

Class is also a strong element in Reyita's life, since she was born and brought up among the poor in Oriente, where women and men worked in the sugar plantations that became so important after the U.S. occupation in l898. Class distinctions also marked the Afro-Cuban community, as Reyita notes that upwardly mobile blacks looked down on the poor, forming their own exclusive associations. Her pretty light-skinned mother had children by several different men, and as she moved around to seek work, would leave some of her children with members of her extended family, a pattern still common to poor women in the Caribbean today. Several of Reyita's sisters and brothers died as children, and she describes how war, illness, lack of public health facilities, and overall poverty decimated many families, especially the young. Reyita's own father was a black rebel soldier in the Wars for Independence, in which her mother also participated, but was left landless and penniless. She also maintains contact with his relatives, particularly her paternal grandmother, and her father's brother's family, with whom she lived part of her childhood.

Gender relations are another particularly intriguing part of the book, which should be read by all feminists who think that Cuban women, and black women in particular, are submissive and obedient. Early in their marriage, Reyita is forced to accept Rubiera's harsh restrictions on her social life and independence, since women with young children are often the most economically and emotionally dependent. She describes her "awakening" when despite her husband's disapproval she joined the Popular Socialist Party, because of their fight for equality.

The matriarch of a family of 118 descendants, Reyita died in 1997 at the age of 95. Her words, her life and her story are a reflection of a Cuba we may not know or understand.

Many thanks to her daughter Daisy, for sharing her with us.

Born on "Three Kings Day" (Dia de los Reyes) Maria De Los Reyes Castillo Bueno will be for us all, simplemente Reyita.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

News by dopper0189, Black Kos Managing Editor

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

A little know part of U.S. immigration law through at least the last century, humanitarian parole allows otherwise inadmissable foreigners to come for the duration of the emergency. Philadelphia Inquirer: Haitian couple in Philadelphia hope for humanitarian parole for kin.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

On the afternoon of Jan. 12, 2010, nursing assistant Andreanna Pierre and her husband, William, a kitchen worker, finished up their shifts at the Gwynedd Square Nursing Center in Lansdale and headed home to devastating news.

An earthquake had crushed much of their homeland.

The ghastly scenes from Haiti horrified them. Somewhere in the catastrophe were their nephew and niece, 13 and 10, orphans in the care of their 30-year-old son.

As the Pierres arranged to go to Haiti to check on the children, Andreanna resolved, "I am their mother, and my husband is their father now."

The house near Port-au-Prince where Jean Wildern Pierre lived with his young cousins, Abdias and Esther Jean-Louis, was standing, but unsafe. For several weeks, all five lived in a tent in the courtyard of the Belgian Embassy until a suitable place could be found.

The Pierres, naturalized U.S. citizens, returned to Philadelphia with heavy hearts. Although their son would soon be able to follow them - after waiting years to immigrate, his visa application was nearing approval - the cousins would not. His attempt to gain their entry to the United States by adopting them had come to naught after a Haitian lawyer took a retainer of $3,000 and did nothing.

Now, the Pierres' dream of uniting the family in their four-bedroom twin in the Northeast depends on "humanitarian parole" - a rarely granted exemption for victims of natural disasters and other emergencies who want to come to America for care.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The US war on drugs created a whole new generation of the dispossessed, with millions of black people denied their rights. The Guardian: America's new Jim Crow system

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Ever since Barack Obama lifted his right hand and took his oath of office, ordinary people and their leaders around the globe have been celebrating our nation's "triumph over race". There's an implicit yet undeniable message embedded in his appearance on the world stage: this is what freedom looks like; this is what democracy can do for you. If you are poor, marginalised, or relegated to an inferior caste, there is hope for you. Trust us. Trust our rules, laws, customs and wars. You, too, can get to the promised land.

Perhaps greater lies have been told in the past century, but they can be counted on one hand. Racial caste is alive and well in America.

Most people don't like it when I say this. It makes them angry. In the "era of colourblindness" there's a nearly fanatical desire to cling to the myth that we as a nation have "moved beyond" race. Here are a few facts that run counter to that triumphant racial narrative:

• There are more African American adults under correctional control today – in prison or jail, on probation or parole – than were enslaved in 1850, a decade before the civil war began.

• As of 2004, more African American men were disfranchised (due to felon disfranchisement laws) than in 1870, the year the 15th amendment was ratified, prohibiting laws that explicitly deny the right to vote on the basis of race.

• A black child born today is less likely to be raised by both parents than a black child born during slavery. The recent disintegration of the African American family is due in large part to the mass imprisonment of black fathers.

• If you take into account prisoners, a large majority of African American men in some urban areas have been labelled felons for life. (In the Chicago area, the figure is nearly 80%.) These men are part of a growing undercaste – not class, caste – permanently relegated, by law, to a second-class status. They can be denied the right to vote, automatically excluded from juries, and legally discriminated against in employment, housing, access to education and public benefits, much as their grandparents and great-grandparents were during the Jim Crow era.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

It's hard to argue against Cornel West on this The Nation: Are We All Black Americans Now?

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

In the months following September 11, my colleague Cornel West offered this insight: national political elites used the devastating attacks to promote the “niggerization of the American people.” West understood that long before 9/11, African-Americans were intimately familiar with terrorism. Through the Jim Crow century, they were routinely and randomly brutalized and murdered by well-organized groups of whites acting beyond the confines of the official state but with the tacit consent of their society. Under the shadow of lynching, black Americans learned what it meant to feel, as West describes, “unsafe, unprotected, subject to random violence, and hated for who they are.” After 9/11 far too many Americans, unaccustomed to this sense of collective intimidation, felt helpless to halt an unjustified war or the erosion of civil liberties. Thus, whether or not they were black, Americans were “niggerized” by the attacks.

In recent months, I have been reminded of Professor West’s analysis because one way to read our current moment is as a blackening of America. The social, economic and political conditions that have long defined African-American life have descended onto a broader population, and it has been instructive to watch how the nation has responded.

Initially, conservatives argued that Tea Party activists had every right to be disgusted with national leadership and to demand swift economic intervention to combat the near 10 percent unemployment rate. Since the mid-1970s, except for a brief dip between 1998 and 2002, unemployment among African-Americans has routinely exceeded 10 percent, yet African-Americans were rarely encouraged to blame systems or organize collectively. Instead blacks were stereotyped as lazy and undeserving. This characterization has been an effective ideological tool for politicians intent on limiting social programs, cutting welfare, ignoring cities, slashing job training and neglecting housing.

Within months, the Tea Party shifted its focus to the deficit. As it did, policy debates about the poor and unemployed came to mirror decades of discourse about black Americans. Extensions of unemployment insurance were decried as “creeping socialism.” Echoing theories of dependency leveled against African-Americans for decades, one conservative blogger suggested that extending unemployment benefits would create “a permanent entitlement and would perpetuate unemployment.” Perhaps, in this moment, Americans understood how dangerously corrosive the characterization of the poor as “idle” is for black people.

This past November the TSA introduced screening procedures that many Americans—liberals and conservatives alike—deemed intrusive, random and demeaning. But for decades urban police forces have regularly employed race-based traffic stops and pedestrian stop-and-frisks in African-American communities. These policing practices have done little to make neighborhoods safer, but they have contributed to massive incarceration rates for black men.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

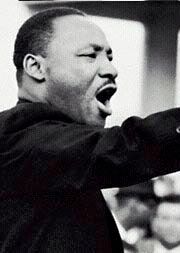

Coalition building 101, Dr. King wasn't just a civil rights leader he was a labor leader. Mercury News: At war against workers while the greedy get a pass

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Once upon a long time ago, a tired man faced an audience of public workers. They were on a wildcat strike, demanding the right to bargain collectively and to have the city for which they worked automatically deduct union dues from their paychecks. The city's conservative mayor had flatly refused these demands.

"You are doing many things here in this struggle," the tired man assured them. "You are demanding that this city will respect the dignity of labor." Too often, he said, folks looked down on people like them, people who did menial or unglamorous work. But he encouraged them not to bemoan their humble state. "All labor has dignity," he said.

On Monday, it will be 43 years since that man was shot from ambush and killed in Memphis, Tenn. Martin Luther King's last public actions were in defense of labor and union rights.

One wonders, then, what he would say of Wisconsin.

Or Indiana, Ohio, Michigan, Florida or any of the other places where, like a contagion, the move to weaken or effectively outlaw unions has spread. One wonders what he would make of a conservative governing ethos that now defines public employees -- teachers, police officers, firefighters -- as the enemy.

Actually, we need not wonder what King would have said, because he already said it. In the speech quoted above, he warned that if America did not use its vast wealth to ensure its people "the basic necessities of life," America was going to hell.

The Baptist preacher in him reared up then, and his voice sang thunder. For all the nation's achievements, he roared, for all its mighty airplanes, submarines and bridges, "It seems that I can hear the God of the universe saying, 'Even though you have done all that, I was hungry and you fed me not. I was naked and you clothed me not. The children of my sons and daughters were in need of economic security and you didn't provide it for them.' "

It will come as a surprise to some that the civil rights leader was also a labor leader, but he was. He had this in common with Asa Philip Randolph, who suffered long years of privation to establish the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. And with Walter Reuther, brutally beaten when he organized sit-down strikes that helped solidify the United Automobile Workers. And with Crystal Lee Sutton, inspiration for the movie "Norma Rae," who lost her job for trying to unionize a textile plant in Roanoke Rapids, N.C.

These people and many others fought to win the rights now being taken away.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

As French troops reportedly take over the aiport in Abidjan, the intense fighting in the Ivory Coast city continues, with no sign that it will abate any time soon. BBC: Ivory Coast crisis: 'Gunfire all the time in Abidjan'

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Heavy artillery fire was heard as troops supporting the UN-recognised, president, Alassane Ouattara, closed in on those backing his rival, Laurent Gbagbo.

But what is life like for those living in the city, having to deal with gunfire all the time?

BBC correspondent Stephane, Abidjan

I can hear the gunfire while I am in my house.

Abidjan resident Khodor, who took this picture, said people looted buildings, leaving nothing behind

One of the worst things is we keep hearing lots of conflicting information. One minute you hear the pro-Ouattara army is taking advantage of the chaos and the situation, the next you hear it is the pro-Gbagbo forces doing that.

I am with my family and we are scared. We feel we cannot leave the house at all. We only went out briefly yesterday and that was to try to find somewhere to buy food.

We are trying to stay as safe as possible and have locked and blocked the doors and window.

We are trying to avoid opening the door if somebody knocks on it as we have heard about robbers targeting neighbourhoods near us and looking for houses to target. We just stay hidden as much as we can.

“We were hoping most of the situation would be sorted by now, but now we don't know”

I think these robbers are taking advantage of the chaos.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------

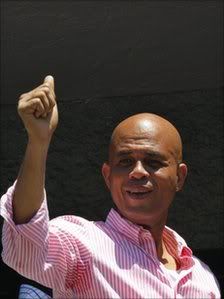

Preliminary results in Haiti's presidential election suggest musician Michel "Sweet Micky" Martelly won the runoff vote on 20 March. BBC: Michel Martelly defeats Mirlande Manigat in vote

-----------------------------------------------------------------------

He defeated ex-senator and former first lady Mirlande Manigat, officials quoted by news agencies say.

Turnout in the second round was high and voting was largely peaceful, although still marred by fraud.

Haiti is struggling to rebuild after the January 2010 earthquake and to cope with a cholera epidemic.

Final results are not expected until 16 April at the earliest.

Mr Martelly benefited from the support of five candidates eliminated in the first round, including his fellow musician Wyclef Jean.

The run-off vote was supposed to take place in January but was delayed.

Observers said the second round was much better organised than the first in November, when turnout was only 23%.

Jude Celestin, who had the backing of outgoing President Rene Preval, took the largest share of the votes in the first round but withdrew from the race after international monitors found there had been widespread fraud in his favour.

Michel Martelly will have to govern a country still struggling after the earthquake in January 2010

------------------------------------------------------------------

*British actor Idris Elba is planning to open a healthcare clinic in Sierra Leone to provide support for sick families in his father’s homeland. Eurweb: Idris Elba to Open Health Clinic in Sierra Leone

------------------------------------------------------------------

The actor was born in England to African parents and admits he’s “embarrassed” he’s never visited his father’s birthplace or his mother’s hometown in Ghana. So he’s putting together plans to boost healthcare in Sierra Leone by teaming up with a cousin to fund a medical unit in the country – and he’s even considering helping the region’s arts industry.

“It’s embarrassing. I have to go. There are plans, serious plans! I can’t wait,” Elba tells Britain’s Observer Magazine. “I want to go to Sierra Leone with something – whether it’s some sort of contribution to healthcare, or to the entertainment industry. My cousin is a nurse; we are talking about opening a clinic.

“I would really like to open a studio in Sierra Leone. It’s a country that can actually house and look like many parts of the world. If I could somehow encourage a film community to use Sierra Leone as the studio in West Africa to make films there, that would be really cool.”

------------------------------------------------------------------

-------------------------------------------------------------------

Voices and Soul

by Justice Putnam

Black Kos Tuesday's Chile, Poetry Editor

In Memoriam: Martin Luther King, Jr.

I

honey people murder mercy U.S.A.

the milkland turn to monsters teach

to kill to violate pull down destroy

the weakly freedom growing fruit

from being born

America

tomorrow yesterday rip rape

exacerbate despoil disfigure

crazy running threat the

deadly thrall

appall belief dispel

the wildlife burn the breast

the onward tongue

the outward hand

deform the normal rainy

riot sunshine shelter wreck

of darkness derogate

delimit blank

explode deprive

assassinate and batten up

like bullets fatten up

the raving greed

reactivate a springtime

terrorizing

death by men by more

than you or I can

STOP

II

They sleep who know a regulated place

or pulse or tide or changing sky

according to some universal

stage direction obvious

like shorewashed shells

we share an afternoon of mourning

in between no next predictable

except for wild reversal hearse rehearsal

bleach the blacklong lunging

ritual of fright insanity and more

deplorable abortion

more and

more

-- June Jordan

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

The front porch is now open. Food on the table today is Cuban, with black beans and rice, yam fritters, and Bistec Empanizado (breaded steak).

Pull up a chair and grab a plate of food.