In 1854 a Mormon expedition under the leadership of W. D. Huntington reported finding some ancient ruins in southeast Utah. Twenty years later, the photographer William Henry Jackson gave the name Hovenweep—a Paiute/Ute word meaning “Deserted Valley”—to the ruins.

In 1150 CE, large pueblos with stone towers were built in the box canyons in the Hovenweep area of present-day Utah by Ancestral Puebloan people (sometimes called Anasazi). The building was done in Mesa Verde style. Both the architectural style and the pottery styles of Hovenweep appear to be closely related to those of the Ancestral Puebloan people at Mesa Verde.

The characteristic architectural features of the pueblos, the stone towers, were built as astronomical observatories. The towers included square and circular towers as well as some D-shaped towers. At some of the D-shaped towers, all four of the major solar events—equinoxes and solstices—could be observed in rooms within the towers.

One of the major feature of Ancestral Puebloan sites is the kiva: an underground ceremonial room. At the Hovenweep towns, the kivas are often associated with the towers.

As with the Ancestral Puebloan people in other areas, such as Mesa Verde and Chaco Canyon, the people at Hoveneep were highly skilled stone masons. Their well-constructed buildings were aesthetically pleasing as well as being functional and long-lasting. Some of the structures utilized large, irregularly shaped boulders as their foundation.

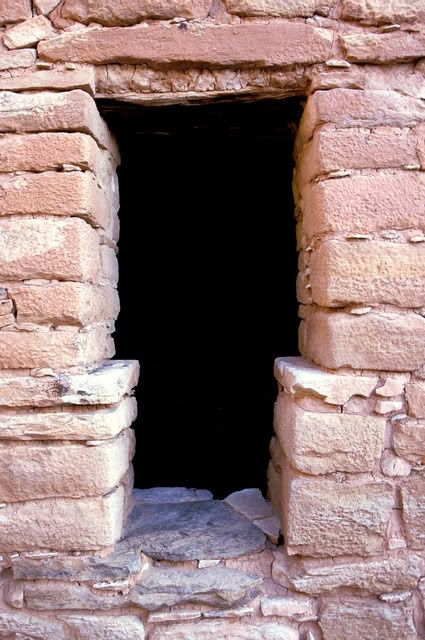

As with the Ancestral Puebloan great houses at Chaco Canyon and Mesa Verde, the builders of the great houses at Hovenweep used T-shaped doors. These doors usually led into public spaces and were not sealed off.

The pueblos were constructed at the heads of box canyons where moisture percolates through the sandstone on the mesa and emerges at the canyon heads in the form of seeps and springs. The Ancestral Puebloan people, utilizing their good knowledge of hydrology, built check dams and reservoirs to control the precious water supply. The check dams above the canyons helped recharge the ground water supply and ensure that the springs within the canyon would continue to provide water throughout the year. This Hovenweep water system allowed them to cultivate garden plots on the terraced slopes of the lower canyons. It also encouraged the growth of native edible or useful plants, such as beeweed, ground cherry, sedges, milkweed, cattail, and wolf berry.

Today, the Hovenweep ruins are a national monument which is administered by the National Park Service.

A prolonged drought from 1276 to 1299 created major problems for the Ancestral Puebloan communities. The drought meant that they could not grow enough food to feed their people. From the Hovenweep area of Utah, the people began a migration south into the Rio Grande Valley in New Mexico and the Little Colorado River Basin in Arizona. Here they established new villages and merged with existing populations to become many of the contemporary Pueblos.

According to modern Pueblo traditions, the ancient communities were abandoned because the serpent god mysteriously left. The serpent god controls rain and fertility. The people left the towns and followed the snake’s trail until they found a river where they once again built their communities.

Cross Posted at Native American Netroots

Cross Posted at Native American Netroots

An ongoing series sponsored by the Native American Netroots team focusing on the current issues faced by American Indian Tribes and current solutions to those issues.