The Big Idea: Rather than push for incremental labor law reforms, or even moderately substantial improvements such as EFCA, progressives should begin building the groundwork for a wholesale overhaul of workplace legislation as radical as the passage of the Norris-LaGuardia Act and the National Labor Relations Act in the early 1930s.

So what the policy prescription? Quite simply, we need to start working to pass . . . the Norris-LaGuardia Act and National Labor Relations Act.

Again.

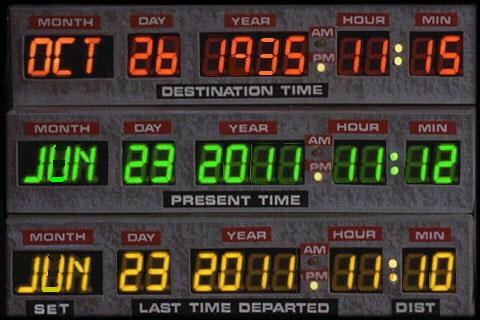

Call Huey Lewis and Doc Brown, because we're gonna

have to go back in time if we want to move forward.

In the middle part of the last decade, the American labor movement coalesced around a new keystone for its legislative agenda: the Employee Free Choice Act. First introduced in early 2007, EFCA was designed to make it easier for workers to form unions free of employer coercion and intimidation. In short, the act would have: 1) allowed employees to choose a union through majority signup, rather than through National Labor Relations Board-run elections, which are often fraught with

employer threats and firings; 2) allowed unions to request arbitration of a first contract, and; 3) toughened penalties for violations of the National Labor Relations Act, which is today scoffed at by employers who routinely break the law with little consequence.

EFCA failed to move through the 110th Congress, due to a Republican filibuster. But the 2008 landslide provided Democrats with the fabled "filibuster-proof" 60-seat majority, and hopes for the bill's passage skyrocketed. Of course, the "filibuster-proof" majority proved anything but, as Al Franken was denied his seat for months by Norm Coleman's endless recounts, and as a handful of Blue Dog Democrats–most notably, Blanche Lincoln–openly flirted with breaking party ranks to join a Republican filibuster. Harry Reid never scheduled a vote on the legislation, and the White House engaged in no public arm-twisting to convince the recalcitrant Blue Dogs to vote for cloture. Regardless of the motivations of the Democratic leadership in the Senate and the White House, the ultimate fate of EFCA was a silent death. It was taken off life support by the election of Speaker John Boehner, but hope for its passage had evaporated months before.

Naturally, unions and their supporters tried to determine why EFCA didn't make it. Blanche Lincoln and her fellow DINOs quite rightly took a lot of the blame, and the president and Senate leadership were generally perceived as at least responsible for enabling the Blue Dogs. Some felt that reform proponents should have dropped the majority signup provision from the bill, which might have appeased the Lincoln faction and allowed passage of the milder improvements.

But largely lost in the recriminations over EFCA's failure was a key argument–that the bill didn't go far enough.

The motivation behind EFCA, after all, was to build workplace democracy and strengthen collective bargaining by fixing a broken law dedicated to those very principles–the National Labor Relations Act. The goal of the NLRA, enacted in 1935, was to create a stable national framework for employee representation in the workplace at a time when it was utterly lacking. Section 1 of the Act concludes:

It is declared to be the policy of the United States to eliminate the causes of certain substantial obstructions to the free flow of commerce and to mitigate and eliminate these obstructions when they have occurred by encouraging the practice and procedure of collective bargaining and by protecting the exercise by workers of full freedom of association, self- organization, and designation of representatives of their own choosing, for the purpose of negotiating the terms and conditions of their employment or other mutual aid or protection.

To achieve that goal–one unashamedly in favor of unionization–Senator Robert Wagner of New York, the act's sponsor and intellectual father, crafted a law that recognized a broad right among employees to organize and provide mutual aid in the workplace. Coming on the heels of 1932's Norris-LaGuardia Act, which forbade federal courts from issuing injunctions against striking workers, the NLRA provided long-needed legal backing to unionists who had been at the mercies of judges and local politicians. The results were striking. Emboldened by the freedom from legal shackles, workers quickly began to build strength in their workplaces. Union membership, which had stagnated during the post-WWI period that historian Irving Bernstein famously named "the lean years," nearly doubled as a percentage of the workforce between 1935 and 1940. And although the rate of union growth slowed from its wildfire pace in subsequent years, union density continued to build through 1960–a trend mirrored in the rise of median American incomes.

So what happened? How did we go from an America with nearly 40% of private sector employees belonging to labor unions, to an America where fewer than 10% of private sector are union members? And how can we turn the tide? In recent decades, unions have made organizing a priority, and have adopted innovative strategies to bring more workers into the ranks, yet have found themselves largely stymied outside of the public sector. (And as you've noticed, things ain't exactly going that well there these days.) The amendments to the NLRA contained in EFCA would have theoretically removed some of the barriers to organizing, but even if EFCA hadn't been defeated in no small part because of a timid Democratic Party, would it have really had a restructuring effect on the workplace similar to that of the passage of the original NLRA?

In his fine new book, Reviving the Strike, union lawyer Joe Burns makes a convincing case that EFCA would have been a half-measure. It's not his main point–Burns isn't all that concerned about legislative reform, and in fact believes that "[w]hile a worker-friendly government administration can influence labor law around the edges, merely electing Democrats instead of Republicans will not change the basic rules of bargaining." Instead, Burns argues passionately that unions will never build strength until they recapture the ability to deny employers wealth and power by striking, and striking effectively. In developing that thesis, Burns tells the story of how labor built worker power through the smart and aggressive use of the strike in the '30s and '40s–and how, over the ensuing decades, the right to strike in a meaningful way was gradually strangled. And in so doing, he answers the question of how the promise of the NLRA and Norris-LaGuardia evaporated.

Burns relates not only the famous union successes of the '30s, like the Minneapolis Teamster strike and the Flint sit-down strike, but entire categories of labor action that have been extinct for nearly 60 years–solidarity strikes and secondary boycotts. It was these latter tactics, Burns argues, that made the threat of the strike such an effective tool.

The Flint sit-down strike.

Where a "strike," as we usually think about it today, is what labor lawyers call a "primary strike"–that is, workers withholding their labor from their own employer–solidarity (or "sympathy," or "secondary") strikes involve workers who strike to support a primary strike. Burns gives an example of employees of an auto parts manufacturer who strike their employer, and who then see Teamsters refuse to transport the parts, and the UAW refuse to build cars with the parts. Without the secondary strikes, the parts manufacturer would likely be able to hire scab replacements, continue production and continue to sell its parts. But the secondary strikes would deny the manufacturer the ability to through the strike, and pressure it into dealing with its employees. Likewise, secondary boycotts target a struck employer though that employer's customers, by urging consumers to avoid not just the struck employer's products or services, but the

customer's products, services, or stores. In

Reviving the Strike, Burns demonstrates how critical these tools, as well as well-organized primary strikes, were to the growth of unions in the wake of Norris-LaGuardia and the NLRA. Without the fear of having their strikes, both primary and secondary, enjoined by reactionary judges, and with the stability created by the NLRA, unions were free to develop aggressive strategies to maximize their solidarity, and, by extension, their power.

And, as discussed above, that's just what happened through the mid-20th century. But within just a few years of the passage of the NLRA, the employers and their allies in the courts and in Congress began to strike back. And Burns chronicles that story of the erosion of progressive labor law very well. The most critical attack on the spirit of the act came in 1948 with the passage of the Taft-Hartley Act. Taft-Hartley was a suite of amendments to the NLRA, each aimed at curtailing union strength. As Burns writes, "trade unionists had denounced Taft-Hartley as the 'Slave Labor Act,' believing that its passage would lead to the destruction of the labor movement. Unfortunately, they were correct." Two of Taft-Hartley's most odious provisions banned secondary strikes and boycotts, and authorized the NLRB to pursue injunctions against unions engaged in secondary action. To quote Burns: "In one fell swoop, Taft-Hartley made illegal the very tactics most responsible for labor's successes in the 1930s." The free speech rights of unions were effectively eviscerated.

Moreover, Taft-Hartley allowed states to prohibit unions and employers from freely bargaining "union security" clauses, which require employees working under a collective bargaining agreement to join or pay administrative fees to the union that bargains and administers the agreement. In other words, states would be able to decree that unions and employers could no longer choose to ensure that all employees benefiting from a labor contract pay for the services rendered to them by the union under the contract. It would be as if a state ruled that its cities could no longer require that citizens pay taxes for the roads, police and schools that they enjoyed every day. This assault on the freedom to contract was perversely framed, in a harbinger of Luntzian naming, as "right to work" - and a number of Republican-controlled states jumped on the opportunity to ban union security clauses, at the same time implicitly encouraging employees to withhold union dues. The effect was to financially cripple unions in the "free rider" states. Today, you can pretty much overlay a map of free rider states on a map of the states with the lowest hourly earnings, and there won't be much of a difference between the two.

Yet while Taft-Hartley certainly arrested the phenomenal growth of union power, it didn't end it. So Congress came back to twist the NLRA once more, in 1959, with the Landrum-Griffin Act. Landrum-Griffin wasn't as momentous as Taft-Hartley, but it did place further restrictions on the right to strike, and perhaps most importantly, it prohibited employers and unions from freely entering into "hot cargo" agreements. As Burns describes them, hot cargo agreements "stated that [unions] did not have to handle any goods produced by a struck or non-union shop." Prior to Landrum-Griffin, carpenters, for example, could refuse to install door frames fabricated offsite in a non-union factory. In so doing, the carpenters would be able to leverage their strength on the construction project to support their fellow union members in fabrication shops. But with Landrum-Griffin, such self-help–even when bargained freely with the employer–became illegal, and with it, virtually all secondary action.

While Congress was doing its best to choke unions, the courts set to the job with relish. Burns details any number of rulings that chipped away at the letter and spirit of Norris-Laguardia and the NLRA, but two from the era stand out. In 1951, the Supreme Court ruled in NLRB v. Denver Building and Construction Trades Council ("Denver Building Trades") that a construction union picketing a contractor at a jobsite on which other contractors are also present must limit its picketing to a single "reserve gate" dedicated to the primary contractor. That, in conjunction with the newly passed Taft-Hartley amendments, meant that employees of the other contractors could no longer refuse to work on the jobsite in sympathy with the picketing employees–a result that marked the beginning of the erosion of joint control of the construction industry by union craftworkers and their employers.

The other lowlight among court decisions of the time was 1970's Boys Market v. Retail Clerks Local 770, perhaps the coup de grace of a series of cases chipping away at the anti-injunction principles of the Norris-LaGuardia Act. In Boys Market, the court ruled that federal courts could enjoin strikes that an employer alleged to be in breach of a no-strike clause in its collective bargaining agreement with a union. Even if the collective bargaining agreement contained a grievance and arbitration procedure which the parties had agreed on as the venue for adjustment of violations of the contract, and despite the plain language of Norris-Laguardia, the court emphatically revived the anti-union injunction. Norris-Laguardia, as the unionists of the '30s knew it, was in tatters.

The upshot of these regressive blows to the labor reform of the '30s was the gradual decline of the labor movement. Strikes became impotent fist-waving, as employers were often able to bust unions through the unimpeded use of scab labor. Free rider laws essentially wiped out unions in much of the South and Mountain West. Unable to leverage their power for growth, unions ebbed in size and influence. Creative leadership and a commitment to organizing somewhat abated the slide in recent years, but there can be little question that the economic power of unions is a shadow of what it was even thirty years ago.

Scabby the Rat on a cold Ohio picket.

(Photo: Flickr user jeffschuler)

So what can we do to reverse the slide? In

Reviving the Strike, Burns argues that only militant and effective strikes can rebuild labor strength. He dismisses, perhaps too easily, many of the initiatives taken by labor in recent years, such as corporate campaigns that target multiple elements of an employer's business, and the focus on EFCA, as well as most other union political activity. As 2009-11 proved, Burns isn't wrong that funneling money toward Democrats is no panacea. Simply working toward Democratic majorities, with no regard for the makeup of those majorities, doesn't mean that any substantial labor law reform or improved climate for unions will result. And there's little question that a more aggressive and determined approach toward striking will be critical to any union revival. But as Burns himself explains very well, the decline in the effectiveness of the strike is directly tied to years of reactionary lawmaking and jurisprudence.

Whatever else the labor movement does to fight back, it cannot write off labor law reform as hopeless. It has to be smart about it, it has to be ruthless and single-mindedly focused on its long-term goals, and it has to be prepared for a long period during which it changes the hearts and minds of citizens. But big change is possible. We've seen the bad guys do it, with the long march of the right wing's campaign to undo the New Deal; and we've seen the good guys do it, with the sustained, unwavering campaigns for civil rights for racial minorities, women and gays. You can't expect to win overnight, just because a few more Democrats got elected. It takes time to change the terms of the debate so that you can win what you really want.

And what labor should want when it comes to labor law reform is pretty damn simple: restoration of the Norris-LaGuardia Act and restoration of Robert Wagner's original National Labor Relations Act. Freedom from injunctions and the right to exercise "full freedom of association, self-organization and designation of representatives of their own choosing for the purpose of negotiating the terms and conditions of their employment or other mutual aid or protection." No Taft-Hartley or Landrum-Griffin, no restriction on the right to picket allies and supporters of struck and non-union employers, no Denver Building Trades or Boys Market, and no free rider laws pitting North against South. Just the labor framework passed by American legislators not even one lifetime ago, the legislation that empowered workers to build the American middle class.

Does all that–a revitalization of the bold, original spirit of the NLRA and Norris-LaGuardia, a stripping away of more than 50 years of victories for the moneyed classes–seem a bit far-fetched in today's America? Sure. But this is a symposium on Big Ideas, and there aren't any ideas much bigger than that of liberating workers to build a better life. And after all, the quiet revolution of the Thirties undoubtedly seemed a fantasy to the workers of Bernstein's lean years. Yet their children came of age in an era of unprecedented worker power.

Senator Robert Kennedy of New York famously said, "Some people see things as they are and say, 'why?' I dream things that never were and say, 'why not?'" Well, today, we can see things as they were–not all that long ago–and say, "why not?" Why not embrace the vision of Kennedy's predecessor as a senator from New York, Robert Wagner, and set our aim on a real restructuring of workplace relations? We did it before, and we can do it again.