The other day my BFF and I (over 50 years of friendship ought to qualify as forever) were discussing the Komen debacle, and I mentioned that it didn't bother me that Komen had jumped the shark since I never donated to them anyway. Because I am a 15 year breast cancer survivor I guess he thought I might have some interesting reason for this, but when I told him why--that I thought all "pay to run/walk" charity events were a stupid waste of human energy that could be used for something productive, like cleaning up streets--he laughed and said, "You are SUCH a Calvinist!"

I was struck dumb by this statement for two reasons: culturally speaking I was raised as an Irish-American Catholic, and I had a chilling feeling that he might be right. Who would want to be a Calvinist? After all, the Puritans were Calvinists, and no one thinks of them as having any fun. Indeed, they were sorta the embodiment of not-fun.

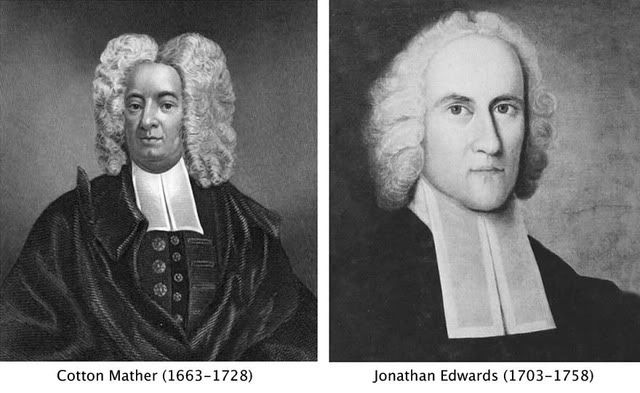

One thought that gave me pause was the memory that I had actually enjoyed studying Puritan New England, and Puritan theology. I had really loved reading Perry Miller's work on "The New England Mind"--I have both volumes, plus his biography of Jonathan Edwards and his two works on American intellectual history. Not only did I find his subject matter interesting, I truly enjoyed Miller's writing style. So I pulled my copy of volume one of "The New England Mind: The Seventeenth Century" off the shelf and started re-reading it. Almost immediately I found this:

The American still prides himself, even when his knowledge is pathetically scanty, of being the heir to the Revolution of 1776.

....

I hope, therefore, that the book will stand against the assaults of those who, in a more modern and insidious guise, deny the importance of ideas in American history, as a way of excusing their own imbecility.

My! Such wonderful, and oddly timely, snark! Not to mention very funny. But of course this was in the Introduction. Surely the main body of the text could not yield any good laughs. I plunged into the first chapter--"The Augustinian Strain of Piety"--which did not seem to be a subject that would lend itself to jokiness of any kind. But I was wrong, Miller could make a good jest even here. Early on in the section on the nature of God there was this:

...Cotton Mather in his heart of hearts never doubted that the divinity was a being remarkably like Cotton Mather.

A bit further on he was explaining the Calvinist objection to gambling, and ended with this:

...we are not to implicate His providence in frivolity. It was a symptom of the waning of piety in the eighteenth century that the colony engineered lotteries, with clerical blessing, for the benefit of Harvard College; devoted as the founders were to that school of the prophets, they would never have regarded it a sufficient excuse for making profits out of divine determinations.

There was one area where the Puritans

were into making profits, and that was business. Their reasoning was a bit convoluted, and the first generation at least did see that there were limits on just how much, and in what manner, profits were not only OK, but definitely a Good Thing. To understand their attitude toward making money we have to take a quick gallop thru their theology. Sorry, but it really is unavoidable. To take a somewhat more complete look with Perry Miller, you can read a few essays in

Errand into the Wilderness, rather than take what might be a tedious trek with

The New England Mind.

The first important point of all Calvinist theology is the omnipotent and unknowable but all-knowing nature of God. Since God is omniscient, and outside of (or beyond) space and time He already knows everything that is going to happen, including who is saved and who is damned. This leads to the doctrine of Predestination--our fate is already sealed the day we are born. Furthermore, due to the Fall of Man, as a result of the disobedience of Adam, human nature is hopelessly corrupt. It is so corrupt and rotten at the core that there is nothing any of us can do to effect our own salvation. The only way to get regenerated is by God bestowing, of his own free, unfettered and fundamentally incomprehensible will, the gift of Grace. This wouldn't seem to leave much room for Churches and ministers and such. After all, it wouldn't matter what one did or didn't do if salvation is arbitrary and there is nothing we can do about it to improve our chance at heaven, and whatever we do, if we are one of the fortunate saved, we won't be going to Hell.

There have been a number of solutions to this fundamental conundrum of Calvinism, and what Perry Miller was chiefly interested in was the develpment of the "covenant theology" in New England, into what he called the Federal theology. The basic idea is that God voluntarily gave up doing whatever he wanted and entered into a contract with human beings. While never going so far as to assert that God would never damn a good person nor save a bad one--God is still free to do so for his own unknowable reasons--if one tries as hard as ever one can to believe and do the right thing, then God will most likely give one a tiny seed of Faith which will enable true belief. With true belief one will just naturally try to do everything that God wants, and thus enjoy the blessings of divine providence. The best way to determine what God wants is to read the Bible and listen to the ministers. The proof of one's being among the elect will be that one is well-behaved, fortunate and successful. So success, which means your business prospers and you are making a profit, is taken by your friends and neighbors as a sign that you are saved.

Thus hard work and sobriety in all things was an excellent idea. Frivolity was a bad idea. Being well-behaved didn't get one into heaven, rather it was a clear sign that one was actually already on the way there. Life was a serious matter, where the saved endeavored in all things to follow God's will. Frivolous behavior, let alone actual bad behavior, demonstrated one was not following God and was in fact on the road to Hell. One was in the world, but not of the world: we are here and must live these lives, but the things of this world should not be the things we are particularly attached to, rather our attachment is to God and the things that God wants. God doesn't want us dancing around Maypoles, He does want us to soberly work hard at what we are given to do. Just don't enjoy it too much.