In the week since Mitt Romney named Paul Ryan as his running mate, both Democrats and Republicans have claimed theirs is the party which will save and protect Medicare, the federal health insurance program for nearly 50 million seniors. But Americans have good reason to believe one side is lying to them. After all, the Affordable Care Act signed into law by President Obama adds 8 years to the Medicare trust fund, realizing $716 billion in savings over 10 years from private insurers, hospitals and waste while expanding today's benefits to include free preventive care and closing the prescription "donut" hole. In stark contrast, in 2011 and 2012 98 percent of Republicans in Congress voted for Paul Ryan's budget plan, which not only repeals the ACA but would transform Medicare into an under-funded voucher scheme the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office confirmed would dramatically shift health care costs onto future elderly. Just as damning, the Ryan plan takes the same $716 billion in savings to partially offset the cost of its budget-busting tax cut windfall for the wealthy.

Of course, there's nothing new in this latest GOP effort to roll back the popular and successful old-age insurance program. The same Republican Party that tried to kill Medicare in the 1960s and gut it in the 1990s now wants to smother it again. The only question now for Mitt Romney and his number two Paul Ryan is how fast.

Republican demagoguery of Medicare began well before President Johnson signed it into law in 1965. "I was there, fighting the fight, voting against Medicare," Bob Dole later boasted, "Because we knew it wouldn't work in 1965." In 1964, George H.W. Bush was among the first to call it "socialized medicine." And three years earlier, Ronald Reagan voiced his opposition:

"One of these days, you and I, are going to spend our sunset years telling our children and our children's children what it once was like in America, when men were free."

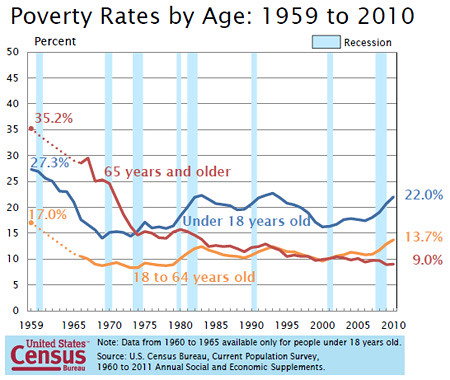

But they were wrong. Medicare did work and Americans in their sunset years were more free, not less. Before Medicare, half of seniors had no health insurance at all, a crisis which has been virtually eliminated. And the poverty rate for Americans 65 and older was cut in half in under 10 years. Far and away the poorest age group in 1959, the elderly saw their poverty rates plummet from 35 to 9 percent by 2010 (see chart below the fold). It's no wonder a

recent Kaiser Family Foundation poll found that Medicare was the single most important health care issue for voters, with 73 percent rating it "extremely" or "very" important.

Of course, for Republicans yesterday defeats are tomorrow's battles. Their long war on Medicare was no different.

Throughout the 1990s, Newt Gingrich, Mitch McConnell and their Republican colleagues renewed the GOP assault. (In 2010, McConnell would falsely charge that Democrats were "sticking it to seniors with cuts to Medicare.") Hoping to slowly but surely undermine the program by shifting its beneficiaries to managed care and private insurance, in 1995 McConnell was among the Republican revolutionaries backing Gingrich's call to slash Medicare spending by $270 billion (or 14 percent) over seven years. As Gingrich put it then:

"We don't want to get rid of it in round one because we don't think it's politically smart," he said. "But we believe that it's going to wither on the vine because we think [seniors] are going to leave it voluntarily."

When President Clinton and his Democratic allies in Congress rushed to defend Medicare from the Republican onslaught,

Gingrich launched a blistering assault:

"Think about a party whose last stand is to frighten 85-year-olds, and you'll understand how totally morally bankrupt the modern Democratic Party is."

But as the debate over health care reform heated up in 2009 and 2010, the leading lights of the Republican Party out their brand of political morality on display. Within a span of a few days,

Michele Bachmann (R-MN) echoed

Marsha Blackburn (R-TN) insisted "what we have to do is wean everybody" off Medicare and Social Security. (Blackburn is now one the leaders of the committee drafting the

2012 Republican platform.) In 2009, Missouri's

Roy Blunt argued that "government should have never gotten into the health care business." That same month, Georgia Rep.

Tom Price, a one-time orthopedic surgeon and then chairman of the Republican Study Group, proclaimed:

"Going down the path of more government will only compound the problem. While the stated goal remains noble, as a physician, I can attest that nothing has had a greater negative effect on the delivery of health care than the federal government's intrusion into medicine through Medicare."

When asked at a 2009 rally,

Rep. Price refused to defend Medicare after stating "we will not rest until we make certain that government-run health care is ended."

All the while, Wisconsin Rep. Paul Ryan was listening and working hard to make it happen.

(Continue reading below the fold.)

In April 2009, 24 months before all but four House Republicans voted for Ryan's plan to ration Medicare, the smaller GOP minority said yea on essentially the same plan. As Steve Benen detailed in the Washington Monthly in the fall of 2009:

In April, 137 Republicans voted in support of a GOP alternative budget. It didn't generate a lot of attention, but the plan, drafted by the House Budget Committee's Rep. Paul Ryan (R-Wis.) called for "replacing the traditional Medicare program with subsidies to help retirees enroll in private health care plans."

The AP noted at the time that Republican leaders were "clearly nervous that votes in favor of the GOP alternative have exposed their members to political danger."

In February 2010, Rep. Ryan unveiled his "

Roadmap for America's Future" and its "slash and privatize" agenda for Social Security and Medicare. Because the value of Ryan's vouchers fails to keep up with the out-of-control rise in premiums in the private health insurance market, America's elderly would be forced to pay more out of pocket or accept less coverage. The

Washington Post's Ezra Klein described the inexorable Republican rationing of Medicare which would then ensue:

The proposal would shift risk from the federal government to seniors themselves. The money seniors would get to buy their own policies would grow more slowly than their health-care costs, and more slowly than their expected Medicare benefits, which means that they'd need to either cut back on how comprehensive their insurance is or how much health-care they purchase. Exacerbating the situation -- and this is important -- Medicare currently pays providers less and works more efficiently than private insurers, so seniors trying to purchase a plan equivalent to Medicare would pay more for it on the private market.

It's hard, given the constraints of our current debate, to call something "rationing" without being accused of slurring it. But this is rationing, and that's not a slur. This is the government capping its payments and moderating their growth in such a way that many seniors will not get the care they need.

(Of course, Ryan left out the real culprit—the

private insurance market. But with 50 million uninsured, another 25 million underinsured, one in five American postponing needed care and medical costs driving over 60 percent of personal bankruptcies, Congressman Ryan is surely right that "rationing happens today.")

It was the Republicans' fear of being the branded "The Party That Killed Medicare" that led GOP leaders to run away from the Ryan Roadmap for America—at least until the 2010 midterms were safely won. As you'll recall, the centerpiece of the Republicans' 2010 effort was an ad campaign to terrify the elderly about changes to Medicare Advantage and the growth of its funding contained in the Affordable Care Act. (Republicans would later go on to vote for exactly the same $500 billion in reductions over 10 years.) That was tough to square with the Paul Ryan's plan to ration Medicare by ending guaranteed health insurance for the elderly and replacing it with under-funded vouchers to buy coverage in the much more expensive private market. Which is why the party ran as far away as possible from Ryan's Roadmap for America before the actual voting took place.

That's why in July 2010 then House Minority Leader John Boehner disowned Ryan's plan. "It's his," Boehner said, adding, "There are parts of it that are well done. Other parts I have some doubts about, in terms of how good the policy is." With only 13 co-sponsors that summer, Paul Ryan himself denied his was blueprint was the GOP's. As Ryan put in August 2010, "My plan is not the Republican Party's platform and was never intended to be."

Not, that is, until Republicans secured their massive new House majority in November 2010. (Which is why, by the way, Senate Republican leaders Mitch McConnell and Jon Kyl were furious with RNC chairman Michael Steele over his "Seniors Bill of Rights" promising "no cuts to Medicare.")

But victory won, version 2.0 of Ryan's "Roadmap for America's Future" now known as the "Path to Prosperity" became the basis for the House Republican budget. In April 2011, 235 House Republicans and 40 GOP senators voted for Ryan's budget and its inevitable rationing of Medicare.

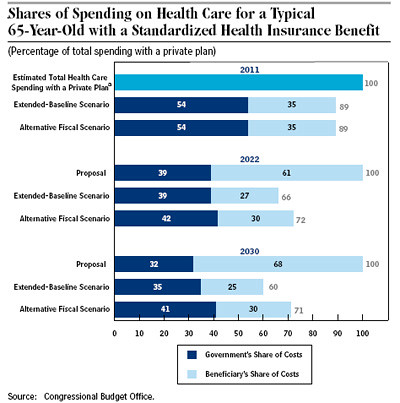

To be sure, the Ryan budget blessed by Republicans on Capitol Hill means de facto rationing for the system that today serves 46 million American seniors. As the CBO documented last year, Ryan's plan to replace public insurance provided by the government with vouchers for the elderly to buy their own coverage in the private market means getting less care for more money. The CBO analysis concluded that "a typical beneficiary would spend more for health care under the proposal." At $6,500 a year, make that, as Director Douglas Elmendorf explained, a lot more.

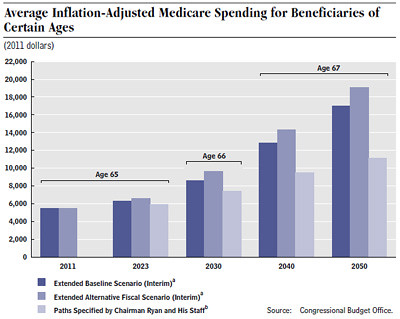

Under the proposal, most elderly people who would be entitled to premium support payments would pay more for their health care than they would pay under the current Medicare system. For a typical 65-year-old with average health spending enrolled in a plan with benefits similar to those currently provided by Medicare, CBO estimated the beneficiary's spending on premiums and out-of-pocket expenditures as a share of a benchmark amount: what total health care spending would be if a private insurer covered the beneficiary. By 2030, the beneficiary's share would be 68 percent of that benchmark under the proposal, 25 percent under the extended-baseline scenario, and 30 percent under the alternative fiscal scenario.

Last year, Nobel Prize-winning economist Paul Krugman explained the dynamic at work. If past performance is any indication of future results, the Ryan voucher scheme would mean big problems for those now under 55 years old and for the U.S. budget.

The larger point is that we don't have a Medicare problem, we have a health care cost problem. And Medicare actually does a better job of controlling costs than private insurers -- not remotely good enough, but better...

If Medicare costs had risen as fast as private insurance premiums, it would cost around 40 percent more than it does. If private insurers had done as well as Medicare at controlling costs, insurance would be a lot cheaper.

In March 2011, Ezra Klein of the Washington Post made much the same point. "The private health-insurance market has exacerbated cost growth in Medicare," he noted, adding, "Medicare's costs have grown more slowly than private health insurance and Medicare's premiums are about 20 percent lower than private health-care insurance." Last June, Klein recounted the sad history of Republicans' recent efforts to privatize the delivery of Medicare benefits:

What they've got in mind already exists in Medicare. "Our premium-support plan is modeled after the Medicare Part D prescription-drug program," Paul Ryan (R-Wis.) told me. But Part D hasn't controlled costs. Instead, premiums have risen by 57 percent since 2006, and the program is expected to see nearly 10 percent growth in annual costs over the next decade.

Moreover, this isn't the first time we've tried to let private insurers into Medicare to work their magic. The Medicare Advantage program, which invited private insurers to offer managed-care options to Medicare beneficiaries, was expected to save money, but it ended up costing about 120 percent of what Medicare costs.

Which is why as 2011 progressed, Republicans once again began to get cold feet about the Ryan Medicare privatization scheme they virtually all supported. With

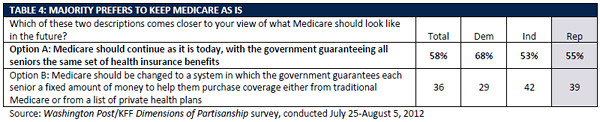

opposition running as high as 65 percent, even die- hards like

Michele Bachmann "put an asterisk" next to her vote for the bill, announcing, "I'm concerned about shifting the cost burden to seniors." (As recent polls from

National Journal and the

Kaiser Family Foundation show, voters--including Republicans--remains strongly opposed.)

Which is why in December 2011, using Oregon Democratic Sen. Ron Wyden as cover, Paul Ryan introduced a new version of his voucher scheme, this time to keep traditional government Medicare as a "public option" future beneficiaries could choose.

The Ryan-Wyden proposal, or "Ryden" plan, if you will, looks a lot like the Medicare prescription from 2010's Domenici/Rivlin blueprint. Unlike Ryan's previous attempt to end Medicare as we know, Ryden maintains traditional fee-for-service government insurance as one option. As the New York Times explained:

Congress would establish an insurance exchange for Medicare beneficiaries. Private plans would compete with the traditional Medicare program and would have to provide benefits of the same or greater value. The federal contribution in each region would be based on the cost of the second-cheapest option, whether that was a private plan or traditional Medicare.

In addition, the growth of Medicare would be capped. In general, spending would not be allowed to increase more than the growth of the economy, plus one percentage point -- a slower rate of increase than Medicare has historically experienced.

Which is just one reason

why Democrats hate the Wyden initiative. Rep.

Jim McDermott (D-WA) told

Bloomberg News, "I don't know why Ron Wyden is giving cover" to Ryan. "For starters, this is bad policy and a complete political loser," one Democratic aide said. "On top of the terrible politics, they even admit that it dismantles Medicare but achieves no budgetary savings while doing so—the worst of all worlds."

That worst of all worlds was embodied in Ryan's 2012 House Republican budget, one which this spring garnered the votes of 228 GOP Representatives and 41 Senators. (That's why Senator Wyden voted no, opposition he reiterated this week.)

Looking at the CBO's March 2012 assessment of the new House GOP budget, ThinkProgress explained why version 2.0 of Ryan's voucher program was little better than the first:

Beginning in 2023, the guaranteed Medicare benefit would be transformed into a government-financed "premium support" system. Seniors currently under the age of 55 could use their government contribution to purchase insurance from an exchange of private plans or--unlike Ryan's original budget--traditional fee-for-service Medicare...

But the budget does not take sufficient precautions to prevent insurers from cherry-picking the healthiest beneficiaries from traditional Medicare and leaving sicker applicants to the government. As a result, traditional Medicare costs could skyrocket, forcing even more seniors out of the government program. The budget also adopts a per capita cost cap of GDP growth plus 0.5 percent, without specifying how it would enforce it. This makes it likely that the cap would limit the government contribution provided to beneficiaries and since the proposed growth rate is much slower than the projected growth in health care costs, CBO estimates that new beneficiaries could pay up to $2,200 more by 2030 and up to $8,000 more by 2050. Finally, the budget would also raise Medicare's age of eligibility to 67.

Even though the new Ryan plan's endorsement of a competitive exchange for rival health insurance plans is in essence "a vindication of the Affordable Care Act," the Obama White House quickly rejected the Ryden scheme. For President Obama's opposition, the repeal of the Affordable Care Act and its benefits for seniors was just the beginning:

"We are concerned that Wyden-Ryan, like Congressman Ryan's earlier proposal, would undermine, rather than strengthen, Medicare," said White House Communications Director Dan Pfeiffer. "The Wyden-Ryan scheme could, over time, cause the traditional Medicare program to "wither on the vine" because it would raise premiums, forcing many seniors to leave traditional Medicare and join private plans. And it would shift costs from the government to seniors. At the end of the day, this plan would end Medicare as we know it for millions of seniors. Wyden-Ryan is the wrong way to reform Medicare."

Of course, for

Mitt Romney, his running mate's latest gambit is the perfect way to reform Medicare. Romney didn't just merely proclaim in his

59-point, 162-page "Believe in America" manifesto that "the plan put forward by Congressman Paul Ryan makes important strides in the right direction" and repeatedly claim he would have signed the 2011 House GOP budget if it crossed his desk. This week, he announced their plans are "

close to identical." A quick glance at

his website confirms that judgment:

"Traditional" fee-for-service Medicare will be offered by the government as an insurance plan, meaning that seniors can purchase that form of coverage if they prefer it; however, if it costs the government more to provide that service than it costs private plans to offer their versions, then the premiums charged by the government will have to be higher and seniors will have to pay the difference to enroll in the traditional Medicare option."

As Think Progress warned, over time private insurers would cherry-pick healthier seniors, leaving the sicker pool remaining in traditional Medicare with to pay their increasing see premiums with under-funded vouchers.

Put another way, Medicare would "wither on the vine," indeed. Nevertheless, Medicare's would-be killers—the same Republicans who slandered Democrats with the charge of creating "death panels" which would "pull the plug on grandma" and see seniors "put to death"—now pretend to be its saviors. As Paul Krugman lamented two years ago:

"Don't cut Medicare. The reform bills passed by the House and Senate cut Medicare by approximately $500 billion. This is wrong." So declared Newt Gingrich, the former speaker of the House, in a recent op-ed article written with John Goodman, the president of the National Center for Policy Analysis.

And irony died.

Looking over the data regarding Medicare's superior costs performance compared to private insurance, Paul Krugman concluded:

"It's a mystery why anyone claims that shifting more people into private insurance is a good idea. Actually, no, it isn't a mystery; it's an outrage."

While Republicans want to destroy the program in order to save it, Democrats have a simple solution for providing health insurance for the elderly today and tomorrow. As

Nancy Pelosi put it, "It's called Medicare."